By Daniel Newman

EIG is tracking COVID-19’s impact on prospective entrepreneurial activity in the United States with weekly data on business formation provided by the U.S. Census Bureau. The statistics below focus on “high-propensity” business applications, a specific subset of applications for new Employer Identification Numbers (EINs) identified by the Census Bureau as having a high likelihood of becoming active businesses with employees within several months after filing. We refer to these high-propensity applications as “likely employers” here.

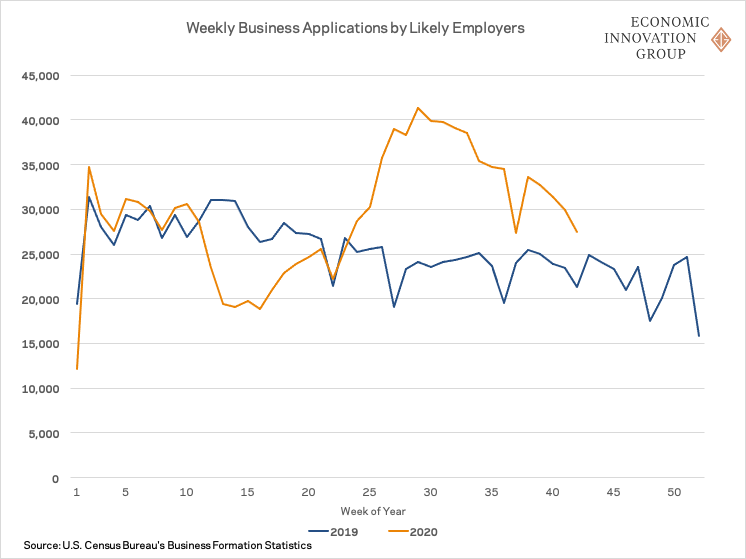

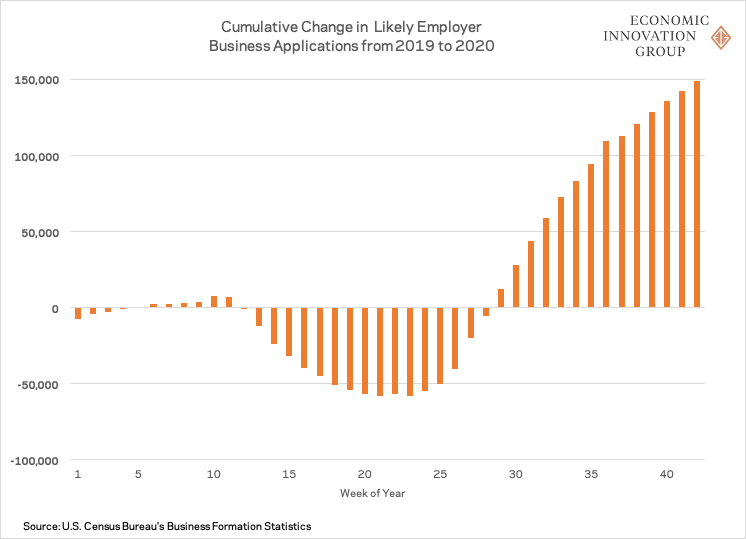

In the wake of an abrupt falloff in nationwide business formation at the start of the pandemic, business applications from likely employers have surged in recent months. Nearly 150,000 additional applications have been filed so far in 2020 compared with this point last year, helping shatter the quarterly record for submitted applications. The elevated numbers have more than compensated for the initial gap in business formation that opened up early in the pandemic: Likely employer applications so far this year total over 1.2 million—a jump of nearly 14 percent over the same period in 2019.

Even though the rate of filings is slowly drifting back down toward pre-pandemic levels, the pace remains well-above last year’s—a dramatic turnaround from the springtime dropoff. In the week ending October 17th (week 42 of 2020), likely employers submitted 27,500 applications, representing a substantial 29 percent increase over the same week in 2019. Seven states, including major hubs of business formation like Washington and New York, still trail the number of likely employer applications recorded through the same week last year, although all lag by 5 percent or less.

Newly released industry-specific data covering all business applications—not just those likely to hire employees—shows that a handful of diverse sectors are leading the surge, but it is amplified by a major boom in the retail industry, particularly non-store retailers most likely to sell goods online or directly to consumers via home delivery or other means. That sector accounts for just over one-third of the increase in applications through week 40 relative to last year. Other industry categories that have spiked during the pandemic are a mix of those one might expect given how the pandemic has shifted consumer demand, such as truck transportation, and others that come across as initially more surprising, including personal and laundry services as well as food and drinking establishments, both of which were hit hard by spring-time lockdowns and social distancing measures aimed at slowing the virus’ spread. The wide-ranging professional, scientific, and technical services category together with administrative and support jobs are responsible for about 15 percent of the increase. In total, applications are at or above last year’s levels in well over half of the detailed industry categories the data tracks.

Some of these industry sectors are more likely to develop into businesses with active employees than others. But it remains unclear how much of the increase is attributable to entrepreneurs finding opportunity in the crisis and forming likely-employer businesses as opposed to newly unemployed individuals starting their own businesses, either by choice or out of necessity. The latter tend to start non-employer firms in recessions (opting for self-employment), not the likely employers that are best-positioned to fuel a rapid recovery. Nevertheless, the sustained and unprecedentedly high rate of new business applications hints that the current crisis could be part of an accelerating restructuring of the economy, as entrepreneurs and everyday workers adapt to a new economic reality.

Even with the knowledge of which industry sectors are powering the wave of applications there are several reasons to interpret the data with caution: Applications in the manufacturing, retail, health care, and restaurant industries are automatically tagged in the data as businesses likely to hire employees, even if that may not be the case. The data also captures some purchases of existing businesses, so a portion of the upswing could represent a churn in business ownership rather than actual anticipated new business formations. Nevertheless, anecdotal evidence provides good reason to believe that much of the bump is real.

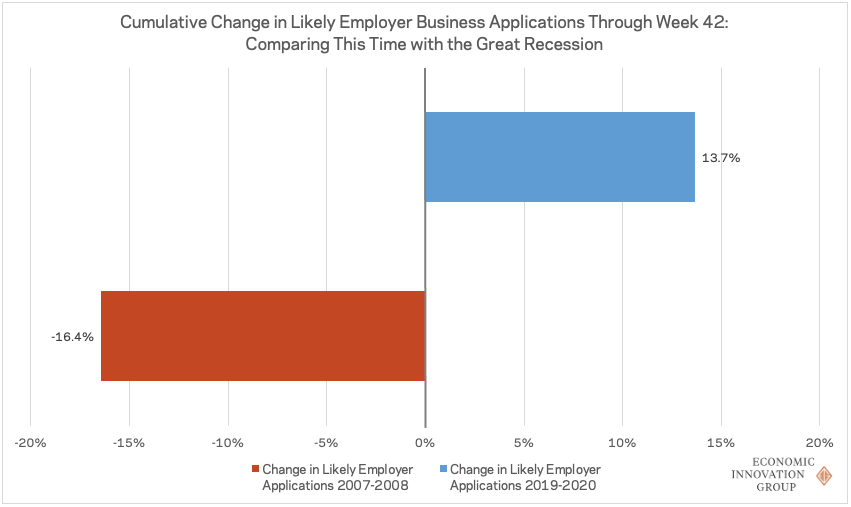

Ultimately, it is not entirely clear why applications are so elevated across such a wide range of industries relative to historical trends when the future is so uncertain and many existing businesses are struggling to adapt to changes in consumer behavior due to the virus. The effect of the current crisis on business formation is playing out quite differently from the Great Recession more than a decade ago. That downturn resulted in a steady decline in business formation in its initial year: Through week 42 of 2008, the total number of applications from likely employers were down by more than 16 percent. After that crisis, startup rates remained depressed all the way through at least 2018, a year in which the United States produced fewer startups than it did in 2001, during a more traditional recession. The fact that house prices and asset prices generally have remained buoyant throughout the pandemic recession could provide one explanation for why indicators of entrepreneurial activity look so healthy—the capital sources many entrepreneurs rely on to launch their businesses remain relatively unaffected by the crisis.

Despite this seemingly promising trend in new business formation, the net effect on the overall count of businesses will be tempered by the scope of closures this year. Almost a quarter of small businesses were shuttered as of late September compared with the start of the year, based on data tracked by Opportunity Insights. While the surge in new business applications is promising, only time will tell how many of these expressions of entrepreneurial intent actually turn into new businesses, and how many of those new businesses go on to survive from there.