By Nora Esposito and Kenan Fikri

While the unprecedented toll the COVID-19-induced shutdowns are taking on the economy is clear in the weekly unemployment figures, the pandemic’s long-term implications for entrepreneurship are already visible in the data and shaping up to be similarly dire.

In response to the crisis, the Census Bureau has begun releasing its new experimental Business Formation Statistics (BFS) dataset on a weekly basis. This allows for an almost real-time look at trends in business applications, a proxy for entrepreneurial activity, as measured by applications for new Employer Identification Numbers (EINs). This analysis looks at only the specific subset of business applications that have a high likelihood of turning into true employer businesses within eight quarters, based on underlying characteristics of the applicant. The Census Bureau defines this group as high propensity businesses.

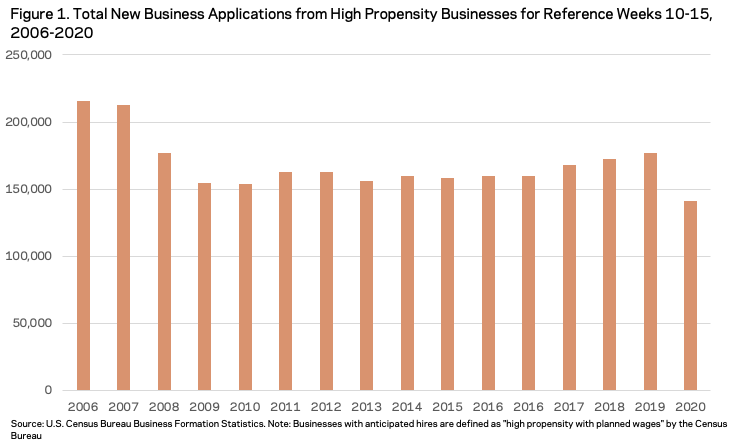

Nationally, high-propensity business applications are down by about one-fifth relative to a year ago. Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of new EIN applications from high propensity businesses for weeks 10 through 15 of each calendar year since 2006. In 2020, this time period covers from March 1st through April 11th.1 Examining this same six-week window each year helps account for seasonal fluctuations in the data and provides a baseline for comparing the impact of COVID-19-related economic shutdowns on the emergence of high propensity businesses. Total new high propensity business applications for reference weeks in 2020 stand at 141,000, approximately 35,600 lower than those of 2019. This 20 percent nationwide fall masks immense variation by region; the Western region registered a 15% reduction, while the North East registered a 31% fall during the same reference weeks. In addition, Figure 1 shows that new high propensity business applications have fallen to their lowest levels on record for the time period.

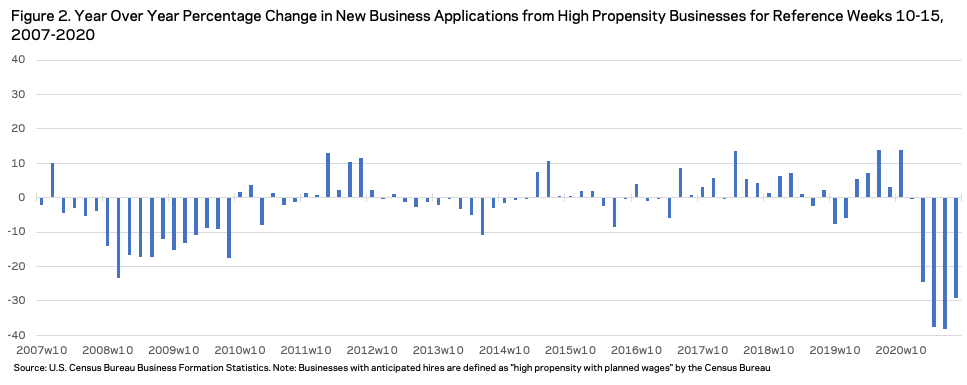

The dropoff in business applications over the past few weeks has been far steeper than any registered during the equivalent weeks during the Great Recession. Figure 2 shows year over year percentage change in new high propensity business applications for each reference week 10 through 15 since 2007. Already, a sharp contraction is visible in the data, almost twice as sharp as what was observed during the same six weeks in 2008. The two crises are very different; the 2007-2009 financial crisis was slower burning than the immediate shock delivered by COVID-19. The depth of the coronavirus recession is becoming clearer each week, but its duration remains a great unknown. During the Great Recession, changes in the number of weekly business applications year over year were negative for a sustained time period. Thereafter, they never again reached pre-recession levels. If economic activity does not resume swiftly from the current crisis, historical experience suggests that business applications–a proxy for entrepreneurship–may not recover from the pandemic’s fallout for quite some time.

While every new business application will not necessarily go on to become an operational business, BFS data provide insight into the plans of likely entrepreneurs. A dearth of new business applications has both immediate and forward-looking implications. Fewer business applications show negative sentiment about the present and future business environment. Additionally, the fall in new applications bodes ill for future business formation. Some of the potential business applications that have evaporated over the past few weeks may simply be postponed, but an unknown share will be scrapped altogether. Suppressed levels of entrepreneurship throughout the 2010s left the economy with a generation of missing startups. The crisis wrought by the pandemic risks pushing the country’s entrepreneurial vitality to a new low. The void left by businesses that never formed will weigh on job creation, innovation, and economic growth for years to come. Rekindling entrepreneurship and business formation must be a centerpiece of the policy agenda to restore the economy once COVID-19 fades.

Nora Esposito is a Research and Policy Fellow and Kenan Fikri is the Director of Research at the Economic Innovation Group.

___________

1 Exact dates covered by reference weeks 10 through 15 vary slightly in other years, see the Census Bureau’s BFS Weekly Data Dictionary for exact dates.