Advancing Economic Development in Persistent-Poverty Communities

Advancing Economic Development in Persistent-Poverty Communities

Overview

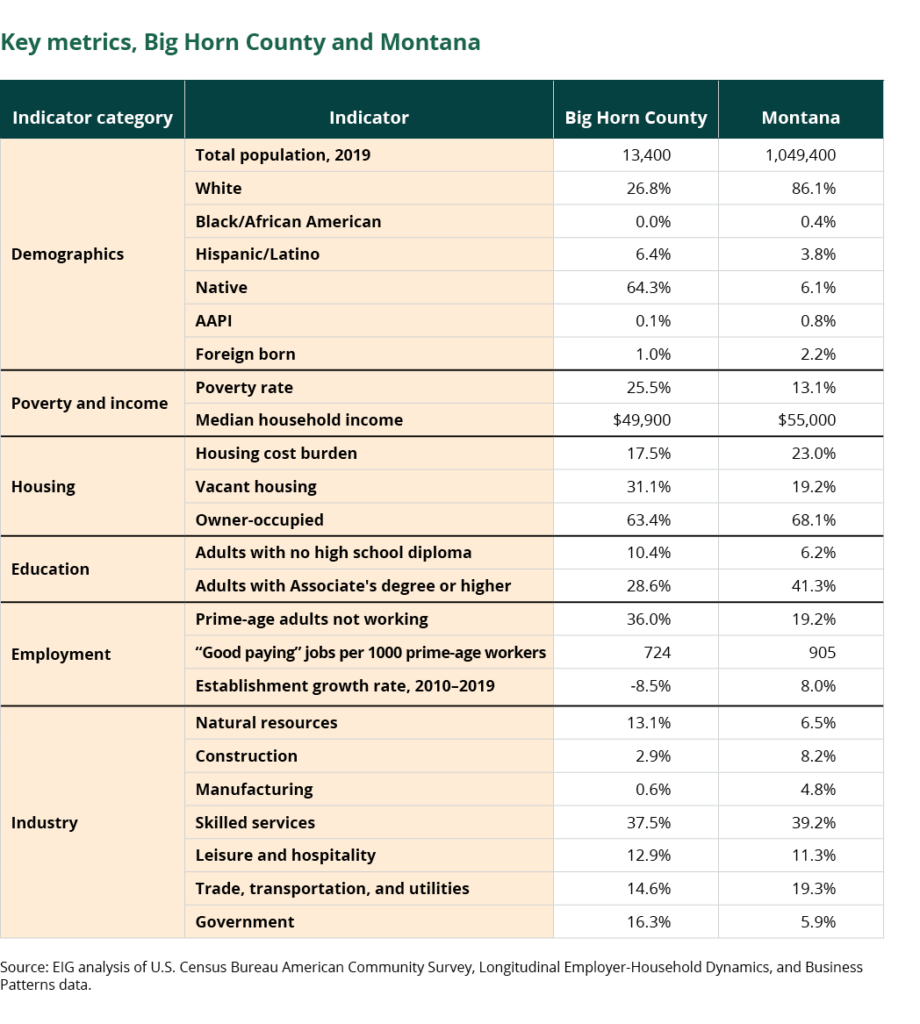

Big Horn County is a rural community of over 13,000 people located in southeastern Montana, about an hour drive from Billings, the most populous city in the state. Two-thirds of the county’s population identify as Native American,[1] and the county’s persistent-poverty status is closely linked with the presence of two reservations: the Crow Indian Reservation, which covers nearly two-thirds of the county, and a small portion of the neighboring Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. Both on and off the reservation, many of the county’s economic development priorities revolve around housing quality, adequate service provision, and job access and quality.

The local economy is largely centered around agriculture, government services, and coal extraction—the latter of which was a one-time source of valuable jobs and revenue that has slowed as an economic engine in recent years, prompting the urgent need for economic diversification. Tourism and recreation represent a relatively minor share of the local economy but offer one of the few near-term opportunities for economic reinvention. A proud tribal cultural identity that prizes independence and self-sufficiency offers unique opportunities to incubate Native entrepreneurs and enterprises rooted in the local culture.

Geography and background

Big Horn County is a sprawling rural community in southeastern Montana defined by the presence of the Crow Indian Reservation—the largest in the state—covering approximately 2.2 million acres.[2] Hardin, the county seat, is home to just over 3,800 residents and provides most of the local options for shopping and other services. The Crow Tribe has a membership of 11,000, of whom 7,900 reside on the reservation, including many who speak Crow as their first language.[3] Crow Agency is the largest tribal community home to more than 3,200 residents alongside most of the tribe’s government functions.[4] Despite the county’s rurality, Big Horn is also influenced by its proximity to fast-growing Billings, which is grappling with an influx of newcomers, rising home prices, and intense competition for scarce workers. Thus far, more negative spillovers from growth in Billings have reached Big Horn County than positive ones.

In general, tribal counties exhibit the highest average poverty rate and the second-lowest share of prime-age adults not working among persistent-poverty counties. Big Horn County’s lagging performance on economic metrics compared to the state overall is starkest when it comes to unemployment, educational attainment, and housing vacancy, although there can be large divergences in conditions within the county. For instance, in the average census tract on the Crow reservation, 43 percent of prime-age adults are not working, while the figure is 20 percentage points lower off the reservation.[5] In Hardin, the poverty rate is 19.6 percent, while just a short drive away in Crow Agency, the poverty rate is 40.6 percent.

A pillar of the county’s economy has been its significant but declining reliance on coal extraction. The impending end of the coal mines as a source of local revenue appears nearer than ever with one estimate that approximately five years of viable reserves remain in the lone-operating tribal mine—a major hurdle to overcome as it still acts as the tribe’s largest single source of revenue, providing about $15 million per year.[6] Between 2012 and 2021, mining-related federal royalty payments to Big Horn’s county government fell by nearly 75 percent.[7] Even though it has been a major source of income, coal extraction has not translated into broad economic prosperity locally, and an over-reliance on the resource has arguably crowded out other private sector development and set the stage for a challenging transition as coal mining declines. The accelerated decline of coal increases the urgency around incubating a more robust private economy both on and off the reservation in Big Horn County.

Social dynamics are another layer that plays into the economic success or struggles of a community. As many rural communities are all too familiar with, issues around mental health and substance abuse have become major concerns in recent years—concerns voiced by residents in our focus groups and interviews in Big Horn, too. A lack of job opportunities can cause a drop in community pride and feelings of self-worth, which can then become a barrier to finding employment, creating a vicious cycle.[8] Even those who do manage to succeed economically are not spared, since the despair that comes with a lack of economic opportunity can also lead to feelings of “social jealousy” toward those in the community who do manage to find relative economic stability.[9]

Key challenges and barriers to revitalization

The challenges to economic development locally are some of those shared by many rural communities across the country. But in Big Horn and other tribal communities, a long history of active and passive discrimination toward the Native American population helps sustain economic and social gaps while fostering distrust. In general, there is a lack of industrial infrastructure and commercial development in the region, and investment is needed to upgrade and expand the housing stock.

The basic economics of both housing construction and repair are stacked against the area

Housing quality and affordability is a major impediment to economic development in Big Horn County, both on and off the reservations. While most of the county’s housing stock consists of owner-occupied single-family homes, there is also a sizable contingent of mobile homes that make up about one-fifth of the housing units[10] The existing housing stock is often poor quality, with more than half of residences rated as “fair” or worse condition. The issue is particularly acute on the reservation where upwards of 60 percent of units are substandard.[11] Many houses have simply been abandoned, leading to a significant share that requires immediate demolition, repair, or renovation.[12]

The lack of adequate housing construction has led to issues of overcrowding as well. County-wide, more than 12 percent of renter-occupied housing units are severely overcrowded, a problem that is particularly prevalent in Hardin and the surrounding area where an estimated 17 percent of renter-occupied housing units are severely overcrowded.[13] In the neighboring county, less than 1 percent of rental housing is similarly affected. In the census tract covering Crow Agency, an estimated 10 percent of owner-occupied housing units are classified as severely overcrowded.[14] One estimate suggests that at least 1,000 housing units are needed to alleviate the issue.[15]

Several local economic development officials ranked the lack of adequate housing as the biggest impediment to attracting workers and the related economic activity that would cater to them. Housing construction in the county is hampered by a skilled labor shortage and rapidly escalating development costs. The shortage of local construction companies and workers is further aggravated by surging demand from larger and more accessible population centers, making it harder for Big Horn residents to hire construction companies and other housing-related services amid the fierce competition.

While these issues cannot be solved overnight, a comprehensive housing study produced by the local economic development organization Beartooth RC&D highlighted the most promising sites that could be developed into housing.[16] Where practical, housing developments could also be paired with other essential services, such as the inclusion of flexible office space for business incubation, job training centers, or childcare facilities. The recent creation of a Big Horn County government position dedicated to countywide housing issues also offers an opportunity to make progress on the comprehensive housing strategy and help promote the development of affordable housing on publicly-owned land.

Small and new businesses are essential to locally driven economic development but struggle to take root

The leakage of economic activity to places outside of the county means that residents’ earnings are not spent and recirculated in the local economy. Instead, they bleed out into surrounding places, especially Billings, draining the county of its already meager income and tax base. Improving access to capital and business support services could foster business activity locally, both on and off the reservation.

With respect to access to capital, Native CDFIs play a vital role in local economic development efforts, but the growing demand for their services has put increased pressure on their operating and loan capital budgets.[17] Increasing the capitalization of Native CDFIs could help alleviate the demand for credit in these communities. Further financial support for revolving loan funds (RLFs) would also be beneficial given the high level of demand for such services from local organizations like Beartooth RC&D. These services are often the only option for helping those who are unbanked or need gap financing for the last portions of a loan, since these are typically services for borrowers who are unable to get funding through traditional routes. Promisingly, Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation, a Native CDFI based in the county, is part of a consortium that won a $45 million award from EDA as part of the Build Back Better Regional Challenge to seed an RLF serving tribal communities in the region and generally help accelerate the development of the indigenous finance sector locally.[18] An additional push to bolster the U.S. Small Business Administration’s 7a loan program could benefit Native communities that have relied heavily on this as a source of business capital in recent years.[19]

With respect to fostering business activity, the complex legal divisions between the county, the tribes, and a host of federal government agencies presents a special challenge for economic development, which often requires coordination across tiers of government and with the private sector. As sovereign and independent entities, reservations have their own political and judicial institutions.[20] Oftentimes, these institutions are unfamiliar to non-tribal business entities, sapping demand to invest, partner, or do business in the area from outside the reservation. For example, the uniform commercial code, which facilitates commerce across states, generally does not apply on reservations.[21] Commercial disputes that arise on Native sovereign land are heard in tribal court, where non-tribal entities may feel that they will be at a disadvantage. Such perceptions—grounded or not—raise the risk premium non-tribal entities associate with doing business on reservations. Such complexities extend to land ownership and use as well, both of which are tightly controlled by the federal government. A little more than one-third of the total land comprising the Crow Reservation is held in trust by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, while the Crow Tribe directly controls 18 percent, and 32 percent of the reservation is actually owned by non-Indians.[22] Such complexity adds to uncertainty, which makes it harder for even land-owning members of the tribe to use land as collateral for loans.

Of course, the goal of economic development initiatives in tribal areas is to cultivate indigenous enterprise, not attract commercial activity from elsewhere. One of the biggest challenges conveyed by interviewees on this front stems from the ambivalent relationship many Native populations, the Crow included, can feel vis-a-vis market society. Cultural and historical preferences for a communal way of life as opposed to a more individualistic mindset play into the comparatively low likelihood that an individual ventures out to start a business on their own. As a result, small business ownership is low and the related support infrastructure is often weak in tribal communities, both in Big Horn County and nationwide. However, recognition of the importance of cultivating Native enterprise is growing, and local organizations such as Plenty Doors are stepping in to fill some of the gaps. Such efforts are vital in tribal areas but also in rural parts of the United States more generally, where entrepreneurship has lagged significantly in recent years. In the end, only 16 new employer businesses were launched in Big Horn County between 2018 and 2020—comparable to similarly rural and/or tribal counties in Montana and creating a needed 190 jobs, but too few to radically change the area’s trajectory.[23] The county has the third-lowest self-employment rate in the state.[24]

Reservations and their nearby counties typically have significantly fewer business establishments of all kinds relative to the surrounding areas, especially when there are fewer than 15,000 residents, and the average revenue of the businesses that do exist tends to be smaller as well.[25] Low credit scores and a lack of collateral when seeking loans are significant roadblocks for many Natives looking to start a business. But ensuring residents are aware of—and utilize—existing assistance programs focused on financial literacy, business development, and support for entrepreneurs could help spur the growth of a local small business sector. The U.S. Government Accountability Office found that there are at least 22 federal programs across seven agencies that give out economic development assistance—such as grants and loans—to tribal communities, but these resources might be hard to know about or access, leading to lower uptake and impact than desired.[26] Providing dedicated spaces for entrepreneurs to meet and share ideas could also be useful in sharing such information and helping new business owners and potential entrepreneurs to make professional connections.

Upgrades to basic infrastructure and service delivery are essential for stoking economic growth

A major roadblock to economic development and business formation are long-standing issues with much of the infrastructure serving the community, ranging from basic utilities like water or waste disposal, to other vital services like grocery stores and health centers. The Crow Reservation no longer has its own full-service grocery store, for instance, and improved access to reliable broadband internet and cell phone service is also in demand. Complicating matters is the fact that the tribe is not a standard municipal government that can levy taxes on residents and properties to fund the provision of social services. Instead, it is dependent on other sources of revenues or grants to finance basic infrastructure.

The American Rescue Plan of 2021 set aside $1.75 billion for Native governments, with some of that specifically directed toward improving tribal housing.[27] Some of it could be used to upgrade water and sewer systems on the reservations. In census tracts encompassing the local reservations, 16.7 percent of housing units on average lacked complete plumbing facilities.[28] In Hardin and the non-reservation portion of the county, the rate was 4.1 percent, which is still high by national standards. According to a recent report from the local economic development district, a new system is planned to treat water for 80 percent of the Crow Reservation after an agreement was made with the federal government to upgrade a regional treatment plant and water system.[29] Until those upgrades can occur, however, the water quality on the reservation remains poor, and many households have issues with frequent dry wells and contamination problems or must rely on costly water delivery services.

The proximity to Billings and presence of major rail and highway infrastructure endows the county with more building blocks for development than some peers, but many of these still need significant improvements. Local leaders mentioned that the rail spur to the industrial park in Hardin, for instance, is not up to the appropriate standards for most heavy industrial or agricultural uses, and the interstate has failed to help the county become a destination in and of itself rather than a way for most motorists to pass through the area—a situation common in many rural communities. In the end, the local consensus is that, since its completion several decades ago, the highway has helped more money flow out of Big Horn County to Billings than it facilitates in the other direction.[30] Reversing some of that flow is a core economic development challenge—and goal—for the county.

The institutional capacity of local governments and economic development organizations is overburdened

In Big Horn County, both the local and tribal governments grapple with challenges that are common to rural and low-income areas of being under-resourced and often understaffed relative to their needs. These dynamics can leave the highest-need places with some of the least institutional capacity, in the economic development jargon. Big Horn County only recently hired its first dedicated economic development staff. Beartooth RC&D conducted the region’s first housing study with the support of special pandemic-era funding through EDA via the CARES Act. The economic development infrastructure on and off the reservation is still being built. If such infrastructure remains underdeveloped relative to the area’s needs, the community will find it difficult to apply for, win, and effectively disburse the funding that it needs. Limits on institutional capacity can perpetuate an area’s economic struggles.

The reservation itself is administered by the tribal government, the county’s largest employer. In some realms this provides a more robust infrastructure for guiding economic and community development, but every entity faces its own set of challenges. Through interviews, tribal members and local economic and workforce development officials expressed a sense that changes in administrations, which take place every four years, can bring large changes in priorities. This can make long-term planning and follow-through difficult; by the same token, it is a challenge shared by non-tribal areas that see a change in party leadership, too (although turnover may stretch especially deep into the bureaucracy in this case). In addition, without a formal office building to house the government, interviewees expressed challenges coordinating with different arms of the public sector. Meanwhile, a growing base of non-governmental entities such as Little Big Horn College strengthen and diversify the ecosystem. As in every community, opening up more opportunities to partner with the growing tribal civic sector is an important priority for enhancing local institutional capacity, too.

The federal government, for its part, needs to collect more information on what programs it offers to tribal communities, how extensive uptake is (and why), and what models are most successful in tribal communities. In part due to the relatively small size of Native populations relative to other ethnic groups, there has been little significant evaluation of the effectiveness of government programs around job training, for example, on this population.[31] The U.S. Government Accountability Office recently called out the need for improved estimating and reporting of federal program commitments to tribal communities in order to identify areas in which better targeting or additional support is needed.[32] Additionally, many development projects have required continuous subsidies or additional federal assistance to maintain operations—meaning the investments failed to stand up something independently viable.[33]

Federal grants provide a vital source of funding for a range of programs locally, yet many local officials lamented the overly burdensome application process as being a major challenge given time and staffing limitations. The complicated grant process can seem biased toward those who are able to afford expert assistance and seems to prioritize those who have already applied for and received grants in the past. The need to obtain multiple bids on a project can be difficult in such a small and remote community, a problem that is similarly applicable to a requirement to obtain matching funds for grants given the relatively limited availability of donors or foundations that could theoretically provide them. Enacted in 2000, Executive Order 13175 permits waivers for tribal entities to get around such obstacles. Raising awareness about such workarounds could help mitigate any structural disadvantages in program design facing tribal entities. More generally, interviewees expressed a desire for more sustained in-person technical assistance from federal agencies or their partners to offer expertise on what is available and how to obtain it.

On this front, a new joint economic development position for the town of Hardin and Big Horn County was funded through a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Community Development Initiative. The role is focused on business and housing development with an ambitious goal of spurring the creation of dozens of new businesses in the next few years. To complement this effort, there is a secondary focus on helping to shepherd through a new affordable housing project, along with an interest in providing a transit option from Hardin to Billings, creating an emergency shelter, and redevelopment of brownfield property.

Assets and opportunities

Big Horn County is frequently described by locals as a close-knit community, both in towns like Hardin and on the reservation, and there is a noted commitment to the community from the small number of business leaders in the area, according to locals and economic development experts. After a series of recent grants and hires, the county’s economic development capacity has been significantly upgraded in recent years. Several ideas are percolating to kickstart the local economy’s needed diversification.

Developing the county into a regional hub for recreation and tourism

Some of the most valuable and underleveraged assets available to Big Horn County and the Crow Reservation are their history and natural environment, consisting of millions of acres of largely unspoiled terrain. The availability of land for recreational and sport activities as well as the potential growth of the local tourism industry are significant. In addition to hydropower, the Yellowtail Dam and the Big Horn River already provide the opportunity for boating and other water-related recreation such as sport fishing, which contributed over $88 million to the local economy in 2017.[34] The county’s most prominent tourism asset is the Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument located just outside Crow Agency and run by the National Park Service. Before the pandemic, the site welcomed 241,000 visitors annually, generating $14.4 million in visitor spending and supporting 220 jobs.[35] While there is not a significant business presence on the reservation, there are many local artisans and craftspeople who could contribute to the growth of tourism centered around the battlefield and other festivals, such as the local Native Days celebration. There are numerous opportunities to build out a more sustainable and year-round tourism industry, and to get visitors to spend more money and time in the county as they pass on the highway.

Embracing a transition to renewable energy resources

There is an opportunity for the area to become economically competitive in the growing renewable energy sector, primarily wind power generation and potentially solar, along with the associated support industries of maintenance, power storage, and worker training.[36] Such a transition would beneficially diversify the local economy while still supporting the aims and goals of tribal governments to cultivate revenue-generating activities under their control.[37] As one interviewee put it, the transformation that must take place locally could be summed up as a move from a mindset of “how do we get money?” off of passive income streams like royalties from mining rights to one of “how do we make money?” The tribe may be able to steward clean energy investments more directly according to its values, too. The county, meanwhile, could look forward to cultivating a more predictable and sustainable revenue stream that helps it more intentionally invest in a more diversified base of future growth.[38]

Identifying ways to ensure workforce development programs are effective

The work of Little Big Horn College (LBHC) provides a solid foundation from which to build out effective workforce development programs. Located on tribal territory in Crow Agency, the college is a valuable county-wide resource that currently enrolls about 250–300 students per year on average. Tribal members make up most of the employees at the college, and many graduates end up working in the education sector as well as local government.

In recent years, the school has offered several apprenticeship and trade education programs focused on local in-demand industries like commercial truck driving, construction, and other housing-related fields, including plumbing, electrical, and carpentry. However, the programs have recorded mixed results to date due to limited sustained enrollment and inconsistent grant funding. Many participants fail to complete the programs, raising the question of whether wraparound services that support other essential personal needs related to safety and health are needed to improve rates of completion and job retention.

Conclusion

This vast and remote community combines the small-city industry of Hardin with the relative economic and social isolation of the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations. The county’s challenges include difficulty achieving economies of scale in financing and development in such a sparsely populated area. The issue is linked with the county’s struggles to attract and sustain commercial activity that can withstand the economic pull of the nearby population center, Billings. The housing stock needs to be expanded and upgraded throughout the county. Local economic development capacity is growing at the county and regional levels thanks to federal funding for new studies and hires, but it needs nurturing and sustained commitment. Fostering attachment to the labor force is a major challenge, and concerns about mental health and substance abuse are widespread. Furthering the economic development of Hardin with infrastructure and workforce upgrades will help Big Horn County as a whole, but on the reservations, incubating private sector activity and local entrepreneurship is a top priority. Such private sector development is becoming even more essential as royalties from local coal mines dry up, leading to a growing reliance on the public sector as the primary source of good-paying jobs.

Notes

- Note: American Indian, Indian, Native, and Native American are used to refer to the people whose lives are characterized by this data. There are many official and unofficial designations of Native heritage from which to choose.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- American Community Survey 2015–19 census tract averages.

- Western, Samuel. “Big Horn County, Montana: Leaving Coal Behind,” Strong Towns, 2021.

- Haggerty, Mark, and Nicole Gentile. “Quitting Fossil Fuels and Reviving Rural America,” Center for American Progress, 2022.

- Compton, Wilson et al. “Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010,” Drug Alcohol Depend, 2014.

- Harrington, Charles. “American Indian Entrepreneurship: A Case for Sustainability,” Journal of Leadership, Management, and Organizational Studies, 2012.

- “Beartooth RC&D Regional Housing Study,” Beartooth RC&D: Resource Conservation and Development, 2022.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- “Beartooth RC&D Regional Housing Study,” Beartooth RC&D: Resource Conservation and Development, 2022.

- U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 5-year estimates 2016–20; Policy Map “Estimated percent of renter-occupied housing units with more than 1.5 occupants per room, between 2016–2020.”

- U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 5-year estimates 2016–20; Policy Map “Estimated percent of owner-occupied housing units with more than 1.5 occupants per room, between 2016–2020.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- “Beartooth RC&D Regional Housing Study,” Beartooth RC&D: Resource Conservation and Development, 2022.

- “Access to Capital and Credit in Native Communities,” The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute, 2016.

- “Four Bands Community Fund Coalition Overarching Narrative,” U.S. Economic Development Administration, 2022.

- Akee, Randall. “The Great Recession and Economic Outcomes for Indigenous Peoples in the United States,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 2021.

- Akee, Randall and Miriam Jorgensen. “Property institutions and business investment on American Indian reservations,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 2014.

- Harrington, Charles. “American Indian Entrepreneurship: A Case for Sustainability,” Journal of Leadership, Management, and Organizational Studies, 2012.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- EIG analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Business Dynamics Statistics data.

- EIG analysis of U.S. Census Bureau ACS 5-year estimates, 2016–20.

- Akee, Randall, Elton Mykerezi, and Richard Todd. “Reservation Nonemployer and Employer Establishments: Data from U.S. Census Longitudinal Business Databases,” Center for Indian Country Development, 2018.

- “Big Horn County, Montana,” Office of the Governor of Montana, 2021.

- “The American Rescue Plan Act,” Department of the Interior: Indian Affairs, 2021.

- U.S. Census Bureau ACS 5-year estimates, 2016–20.

- “Beartooth RC&D Regional Housing Study,” Beartooth RC&D: Resource Conservation and Development, 2022.

- “Beartooth RC&D Regional Housing Study,” Beartooth RC&D: Resource Conservation and Development, 2022.

- Akee, Randall. “Sovereignty and improved economic outcomes for American Indians: Building on the gains made since 1990,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021.

- “Tribal Economic Development: Action is Needed to Better Understand the Extent of Federal Support,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2022.

- Mathers, Rachel. “The Failure of State-Led Economic Development on American Indian Reservations,” The Independent Review, 2012.

- Western, Samuel. “Big Horn County, Montana: Leaving Coal Behind,” Strong Towns, 2021.

- Western, Samuel. “Big Horn County, Montana: Leaving Coal Behind,” Strong Towns, 2021.

- Timer, Adie, Joseph Kane, and Caroline George. “How renewable energy jobs can uplift fossil fuel communities and remake climate politics,” Brookings, 2021.

- Akee, Randall. “Sovereignty and improved economic outcomes for American Indians: Building on the gains made since 1990,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021.

- Haggerty, Mark, and Nicole Gentile. “Quitting Fossil Fuels and Reviving Rural America,” Center for American Progress, 2022.

This report was prepared by the Economic Innovation Group using Federal funds under award ED21HDQ3120059 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.