Advancing Economic Development in Persistent-Poverty Communities

Introduction

In policy debates in the United States, poverty is often thought of as an individual or family issue: a condition of being low income, and oftentimes, dependent on public support to make ends meet. But poverty is also a spatial phenomenon. Numerous communities across the country have been poor for generations: think parts of Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, the southern border, or Chicago’s South Side. These places do not just house poor people; they also seem to perpetuate poverty. Living in them can leave an indelible mark. This report seeks to understand why poverty persists in these communities and identify how federal policy can more effectively address the challenges that keep them poor.

Thanks to recent empirical advances, we now understand that the longer a child is exposed to a high-poverty environment, the less likely it is that they will climb the income ladder as adults. [1] Places shape the future of children via school quality, exposure to violence, pollution, and social influences, among other channels. [2] The social aspects are especially important, with recent research showing that places that foster more connections across class lines improve upward income mobility for residents. [3] Although the causal effects of place on economic outcomes appear weaker for adults, [4] there are myriad avenues through which living in a disadvantaged area inhibits human flourishing. Proximity to environmental hazards, [5] greater exposure to violence, [6] and worse health outcomes [7] are just some of the ways living in a high-poverty neighborhood can harm both children and adults. In general, poverty rates are highly correlated with other socioeconomic indicators; where poverty rates are high, populations are generally suffering on multiple fronts.

In addition, poverty is highly correlated with a lack of work. Nationwide, only 1.8 percent of working age individuals who were employed full-time year-round landed in poverty in 2021, compared to 12.2 percent of those who worked less than full-time and 30 percent for those who did not work at all. [8] Rates of not working vary significantly by geography, sometimes reflecting the poor economic conditions of an area, and sometimes reflecting the deeply ingrained characteristics of a place or population that has functionally become detached from the labor market. Economic development policy has a critical role to play in combating poverty in the United States where poverty stems from regional economic weakness, on the one hand, and the weak labor market connections of a people in a place, on the other.

The intransigence of local poverty matters because it keeps the number of Americans living below the poverty line higher than if opportunity were distributed evenly across the map. For too many Americans, the poverty of their surrounding community inhibits their potential—preventing them from building wealth or connections, reducing human capital formation, or increasing gaps between employment spells. A persistently high poverty rate in an area can be thought of as an alarm bell, signaling to policymakers that something fundamental in the local economy has broken down and prevented these places from fully engaging in U.S. economic life.

And yet, the challenge is by no means insurmountable. The country has made important progress over recent decades. Violent crime rates have dropped precipitously since the early 1990s. [9] Although the number of high-poverty neighborhoods remains stubbornly elevated, fewer poor people are living in extreme poverty, or in communities with a poverty rate above 40 percent. [10] These improvements show that meaningful change is possible, and they should serve to embolden a new generation of federal initiatives to rekindle economic opportunity in persistently poor places and tap into the economic potential of people living in them. As the country begins a fresh cycle coming out of the pandemic, it is time to lay the policy foundations to ensure that another era of economic growth does not come and go, only to leave thousands of the country’s neediest communities, and millions of their residents, behind.

Report Findings

Persistent-poverty communities are in some ways the country’s ultimate left-behind places—areas that have maintained high poverty rates for decades, seemingly detached from the nation’s broader economic growth. The federal response to this enduring challenge has evolved over time. The working definition of persistent poverty was laid out in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which directed certain federal agencies to dedicate at least 10 percent of their funding streams to counties that have had a poverty rate above 20 percent for the past 30 years, a formula referred to as the 10-20-30 provision.

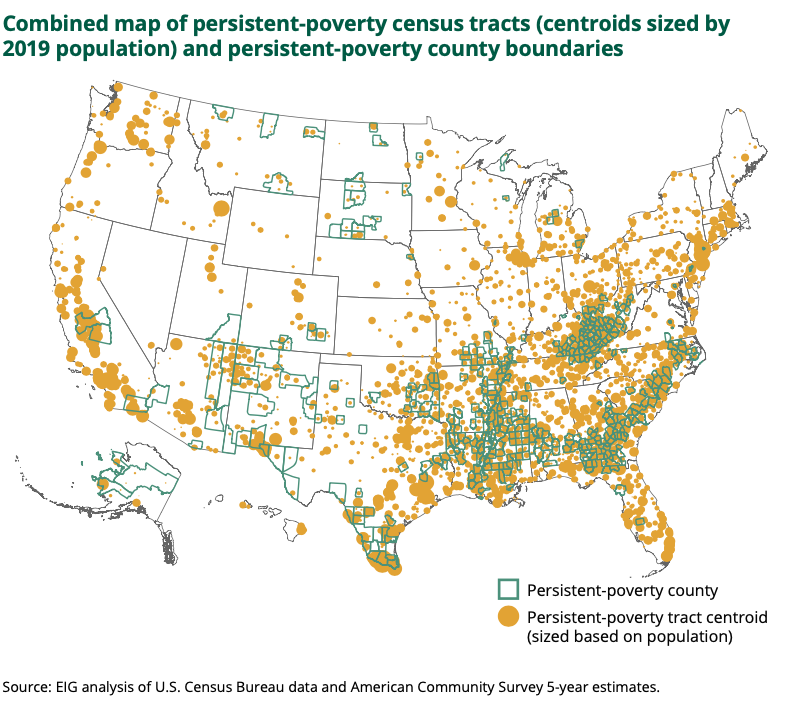

The 10-20-30 framework represents a significant advancement in defining the challenge of persistent poverty and making it a permanent feature of federal policy. However, federal policy still has not risen to meet the full scope and scale of the problem under the framework. Measuring persistent poverty only at the county level misses large areas of persistent poverty in urban settings, because most metropolitan counties are too populous and economically diverse to register as persistently poor county-wide, even though they contain a majority of both the affected communities and the affected populations. Designed to secure set-asides from existing programs, the framework has delivered little impetus to develop novel programs specifically tailored to the problem of persistent poverty. Even the methodology for identifying persistent-poverty communities is not standardized across agencies, leading to large divergences in which counties qualify as persistently poor and undermining needed federal coordination in these areas.

It is time for federal policy to evolve again to support America’s most left behind communities. This report contributes to that evolution in several significant ways, both quantitatively and qualitatively. It puts forth contiguous groups of persistently poor census tracts as a more refined alternative to the current county-only definitions. While these groups are more methodologically complicated to create, they offer a right-sized geography for economic development interventions, more precisely identify areas of persistent poverty within counties, and are better aligned with the empirical evidence on the effects of neighborhoods on individual outcomes and opportunity. Typologies are created to differentiate persistent-poverty communities from each other while also highlighting key commonalities. A development assessment scores communities based on those typologies across 14 distinct metrics to identify strengths and weaknesses in the local economic foundations and to inform development strategies. Finally, a set of case studies provide an analysis of four distinct persistent-poverty communities to help understand the local dynamics that perpetuate poverty—and draw lessons from initiatives past and present that have tried to break the cycle.

The report’s key findings include:

- 35 million Americans reside in a persistent-poverty community. These communities are identified using a novel geography that groups together adjacent persistent-poverty census tracts into distinct persistent-poverty tract groups (PPTGs). Altogether, the approach captures 15 million more Americans living in persistent poverty communities than when counted only at the county-level. Among the hundreds of additional areas of persistent poverty that come into focus are large, urban, and demographically diverse communities such as one in central Los Angeles with a population of 1.2 million, and ones in Chicago and Houston with 500,000 residents each. The approach also offers greater precision in identifying persistent-poverty areas in rural settings.

-

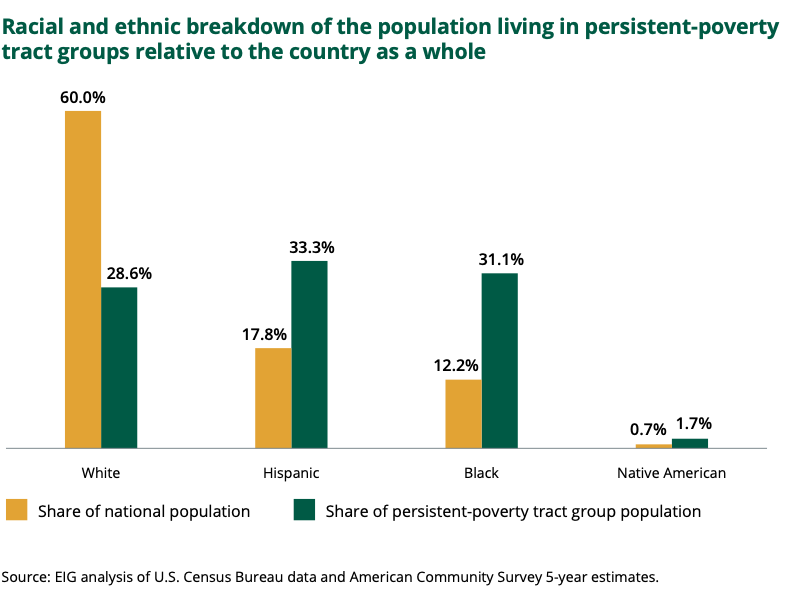

Tract groups are more representative of the population living in persistent- poverty areas. More than twice as many Black and Hispanic Americans are represented in PPTGs than in persistent-poverty counties, as well as 20 percent more white Americans in those PPTGs than at the county level.

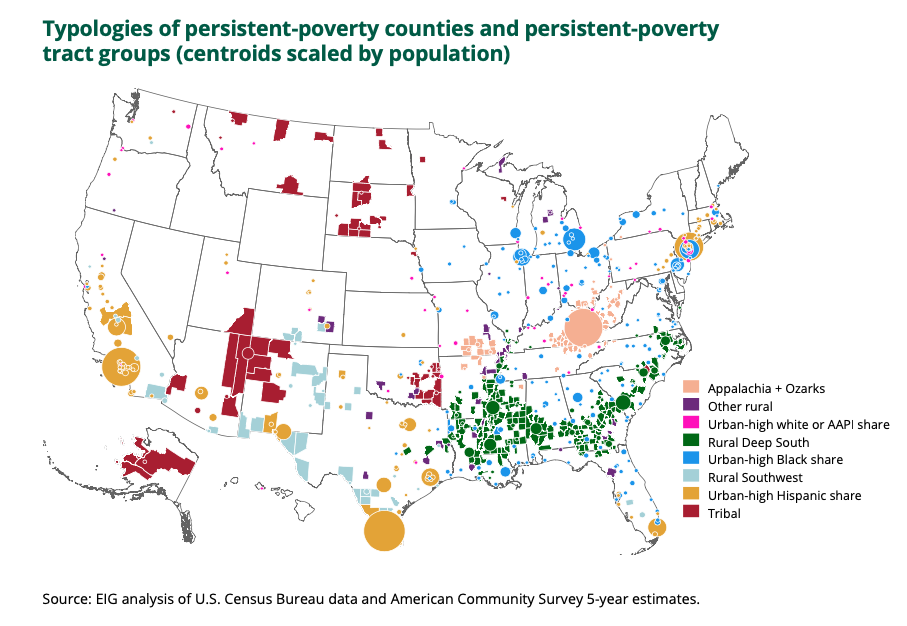

- Race and region define the map of persistent poverty. A single racial or ethnic group tends to predominate in each persistent-poverty area—pointing to the deep historical roots of the challenge everywhere it arises. Blacks are overrepresented in the band of persistent poverty that stretches from East Texas to Southern Virginia, a living legacy of the region’s agricultural and slave-holding past. Many tribal counties in the western states are rich in natural resources, culture, and language. However, a centuries-long pattern of economic and social exclusion has left them with some of the country’s most persistent and widespread pockets of poverty. Many predominantly Hispanic counties along the Southern border also trace their lineage as persistently poor communities back centuries. Similarly, white poverty in Appalachia and the Ozarks is rooted in the economic histories of those regions. Comparable forces of segregation and barriers to opportunity are key protagonists behind persistently poor neighborhoods in American cities. Shared experiences and histories naturally lead to the creation of distinct typologies of persistently poor communities.

- Each typology exhibits different strengths and weaknesses across the building blocks of economic development. Prime-age employment rates and educational attainment tend to be low across all persistent-poverty communities. Affordability tends to be a greater challenge in more urban settings, while proximity to good-paying jobs is rare in rural ones. Measures such as infrastructure quality and upward income mobility vary significantly across the different typologies.

- It is very rare that once-high poverty places eventually turn around. Only 7 percent of counties that were high poverty in 1990 had poverty rates fall comfortably below 20 percent by 2019 and also experienced population growth in the process. Most either benefited from exurban sprawl or growth in the mining and extraction industry. The weak state of private sector development in persistently poor areas likely inhibits more turnarounds from taking hold.

Case studies were conducted in four persistent-poverty communities falling into four different typologies: Phoenix, Arizona (Urban-high Hispanic share); North St. Louis, Missouri (Urban-high Black share); Big Horn County, Montana (Tribal); and Gadsden County, Florida (Rural Deep South). Despite the geographic and cultural differences of these communities, several key themes emerged from these case studies that help to identify the binding constraints on their development. All of these four distinct communities grappled with:

- Disconnection from regional growth: At the regional level, economic growth alone does not necessarily translate into prosperity that reaches persistently poor areas. The very persistence of poverty in South Phoenix exemplifies this, located in one of the fastest-growing regions in the country. The same holds true in St. Louis, where a burgeoning innovation sector has yet to translate into much direct economic opportunity for residents of persistently poor areas.

- Insufficient local institutional capacity: Most persistent-poverty communities are by definition resource-limited, with many needs and a comparatively small tax base given their economic distress. Limited capacity makes it difficult to do basic economic development work, ranging from applying for federal grants to attracting new businesses. For example, Big Horn County, Montana, had no full-time economic development position until recently.

- Inadequate infrastructure: Infrastructure issues large and small hold back growth. For example, residents of North St. Louis pointed out that the poor condition of their infrastructure degrades their quality of life and discourages potential residents and businesses from locating within the area. Meanwhile, plans to develop a freight corridor in Gadsden and build out a rail spur in Big Horn are examples of the types of larger infrastructure investments that could help kickstart the development of private industry were they to come to fruition.

- Anemic small business ecosystems: All four case study communities struggle to foster entrepreneurship and cultivate a healthy small business ecosystem. Some contend with limited access to capital or the leakage of resident earnings to more economically vibrant neighbors. In others, local population loss makes it harder for businesses to survive. All four grapple with the need to cultivate a more robust pipeline of local entrepreneurs.

- Inadequate workforce development systems: Every case study community has employment opportunities for residents able to complete the necessary training and to successfully find and keep a position. However, these opportunities are practically out of reach for many poor residents. Gadsden and St. Louis lack the workforce development infrastructure needed to connect low-skilled workers to higher paying employment at scale. In rural Big Horn, degree completion is a major challenge, and in expansive, decentralized Phoenix, limited transportation access to job centers erects barriers.

Policy Objectives

This report’s quantitative and qualitative analyses reveal a tangled knot of forces at work in most persistent-poverty communities that keep them from escaping poverty. The long-term work of finally, durably, advancing economic development in persistent-poverty communities can begin with a few basic steps: more precision in diagnosing the problem, better alignment of policy tools with community needs, greater cultivation of a local partner network, and a focus on simultaneously incubating private sector activity while strengthening connectivity between poor places and the rest of the economy. There is much that federal agencies can do in collaboration with each other and partners on the ground to set persistently poor communities on a better trajectory. Key themes to guide the next stage of policy ideation and implementation include:

- If the federal government is committed to attacking persistent poverty at its roots, it needs to do two things: invest more in these places and invest more wisely. Based on this report’s methodology, the problem of persistent geographic poverty is at least 72 percent larger by population than the federal government’s current county-based measurement. Given the true scale of the problem, both more direct development-related funding and customized policy solutions that address the unique challenges of persistent-poverty communities are needed. Here, the Recompete Pilot Program may serve as a model of a sizable, flexible, economic development-oriented funding stream that could eventually be scaled.

- Federal partners must better coordinate their interventions to maximize successful outcomes in persistent-poverty communities. Due to the overlapping nature of issues facing persistently poor communities and the scarce resource environment in which most of them operate, a lack of collaboration and coordination across federal agencies hinders effective interventions and ensures each individual federal investment undershoots its potential. Without coordination, there is a much higher risk that isolated investments fail in the absence of complementary initiatives or supportive follow-on activities, squandering already scarce resources when collaboration could lead to better local outcomes without significant new funding.

- Federal goals would be best served by a standardized methodology for defining persistent-poverty areas. Congress should ask the U.S. Census Bureau to set the authoritative qualifying criteria for persistent-poverty communities to be used across all federal agencies. In that process, the Census Bureau should work with affected agencies to explore the feasibility of incorporating census tracts or tract groups into the model. Federal program officials and recipient communities alike would be better served by agencies working off a single, authoritative, complete, and predictably updated map of persistent-poverty areas.

- Congress and federal stakeholders should look beyond the poverty rate and consider other metrics to design place-based policies that target economically distressed areas. Most persistent-poverty communities are embedded in wider areas that are broadly struggling but not necessarily pervasively and persistently poor. The poverty rate itself is fraught with measurement challenges and controversies. When designing and implementing place-based economic development policy, measures such as median incomes and prime-age employment rates should be considered to more precisely target economically lagging areas.

- The core economic development challenge in persistently poor communities is to stimulate private economic activity. Given the anemic state of private sector development in most persistently poor areas, federal interventions must strive to stimulate markets, attract private capital, and empower residents to become productive economic actors. People-based strategies around career pathways, workforce development partnerships, and re-entry programs should be accompanied with more place-based ones around investment incentives and capital solutions, public-private partnerships, and placemaking.

- Given persistent poverty’s deep historical and localized roots, the federal government must support locally-grown strategies and bottom-up capacity building. Truly sustainable economic development strategies stem organically from their environments. The federal government can support such strategies by elevating the problem, setting bold national goals around it, and following through with sustained financial commitments and novel programming. Perhaps most important, however, are direct investments to incubate local capacity in persistent-poverty communities so that they can take control over their futures.

Advancing the economic development of persistently poor places requires strengthening the ties between them and the rest of the nation’s economic and social fabric. Persistent-poverty communities suffer from too little connectivity: too few jobs, too little investment, too much economic and social isolation. The task for policymakers and economic development practitioners is to develop the next generation of programs and tools tailored to the specific needs of persistent-poverty communities to better integrate them into the nation’s economic fold. Some elements of this playbook have already been outlined, but the field of economic development still has more questions than answers and will need to embark on a new era of brainstorming, experimentation, and innovation to rise to the challenge.

Notes

- Chetty and Hendren, 2018.

- Chyn and Katz, 2021; Sharkey and Elwert, 2011.

- Chetty, 2022.

- Chyn and Katz, 2021.

- Downey and Hawkins, 2008; Manduca and Sampson, 2021.

- Sampson, 2018.

- Yang and Scott, 2020.

- Creamer et al., 2022.

- Sampson, 2018.

- Based on the dataset created for this report, a half million fewer people live in a census tract with a poverty rate above 40 percent today compared to 1990.

This report was prepared by the Economic Innovation Group using Federal funds under award ED21HDQ3120059 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.