The Neighborhood Poverty Project

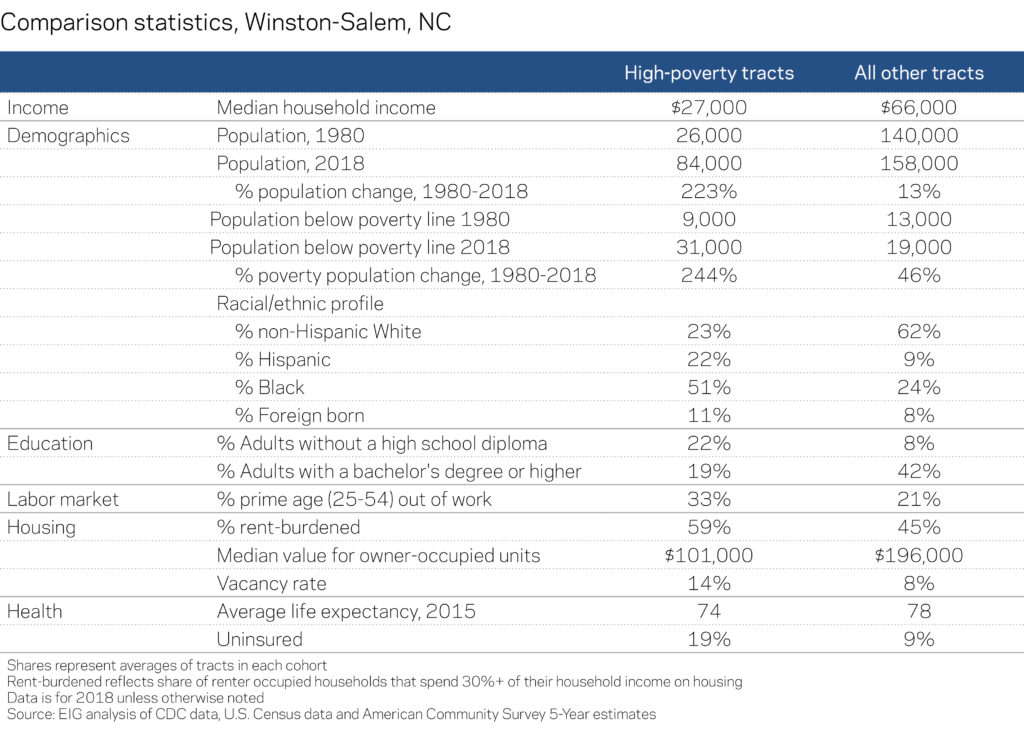

Winston-Salem’s city-wide poverty rate in 2018 stood at 20.6 percent, unchanged from the year prior, and nearly four percentage points higher than its 1980 poverty rate. While the city’s poverty rate looks modest in comparison to cities such as Memphis and Detroit, the proliferation of new high-poverty neighborhoods locally is worrisome. Seventeen neighborhoods in Winston-Salem went from low or moderate poverty in 1980 to high poverty in 2018, representing 28 percent of all the city’s neighborhoods. Meanwhile, the city has made little progress towards reducing its stock of historically high-poverty neighborhoods. Of the nine high-poverty neighborhoods the city had in 1980, just one turned around, while another one switched to moderate poverty. All but one of Winston-Salem’s persistently poor neighborhoods had an even higher poverty rate in 2018 than they did in 1980.

Like many American cities, Winston-Salem has focused its economic development efforts on revitalizing its downtown. The crown jewel of this effort is the city’s Innovation Quarter, a project 20 years in the making that has succeeded in repurposing former industrial buildings into a research park with 90 companies alongside residential developments. This is the only neighborhood in Winston-Salem to pivot from high to low poverty in the last 38 years. Its poverty rate dropped from 43 percent in 1980 to 14 percent in 2018. The successful turnaround of this neighborhood demonstrates both the positive impacts of targeted economic development efforts and how much work is necessary to revitalize a deeply distressed neighborhood.

And yet, so far there have been few observable spillover effects from the city’s Innovation Quarter to adjacent neighborhoods. A neighborhood just to the east saw its poverty rate climb from 20 percent to 46 percent in that same time period, and the neighborhood to the south saw its poverty rate climb from 17 percent to 37 percent. A cluster of persistently poor neighborhoods to the north of the Innovation Quarter continue to have poverty rates above 40 percent.

Further from downtown, poverty has begun to fan out and reach into the close-in suburbs. A 2014 study from Brookings ranked Winston-Salem second in the country for suburban poverty based on 2008-2012 ACS data (Kneebone 2014). More recent data show no improvement since. Entire communities, such as Waughtown and Easton View, have gone from low poverty to high poverty in the past 38 years. One tract in Waughtown saw its poverty rate climb from 11 percent in 1980 to 51 percent in 2018. Some tracts have undergone dramatic demographic shifts over the study period, but not others. The Waughtown tract transitioned from being majority non-Hispanic white in 1980 to majority Hispanic in 2018; other newly poor neighborhoods on the west side of the city are majority white; and the persistently poor neighborhoods to the north of the city remain majority Black.

Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites each make up a little less than one-quarter of the population in Winston-Salem’s high-poverty neighborhoods, while Blacks make up around half. This is a dramatic shift from 1980 when Blacks made up 89 percent of the population of high-poverty neighborhoods, compared to 1 percent for Hispanics and 10 percent for non-Hispanic whites. With over one-third of the city’s residents now living in a high-poverty neighborhood, the economic challenges for the city are increasing. A 2015 income mobility study found that only one county in the United States ranks worse than Winston-Salem’s Forsyth County for poor children having the opportunity to climb the income ladder (Chetty and Hendren 2016). Winston-Salem, like so many other American cities, will struggle to deliver economic opportunity to its residents if high-poverty communities continue to proliferate.