The Neighborhood Poverty Project

City Profiles: Houston, TX

Houston presents a dramatic example of high-poverty neighborhoods radiating out into the suburbs, sprawling alongside America’s now fourth-largest city. Meaningful reductions in poverty have only occurred in the downtown core of the city. Elsewhere, high levels of poverty have persisted in many close-in neighborhoods, while suburbs and exurbs, especially to the east of downtown, have seen increasing poverty take root in areas that were once comfortably middle class.

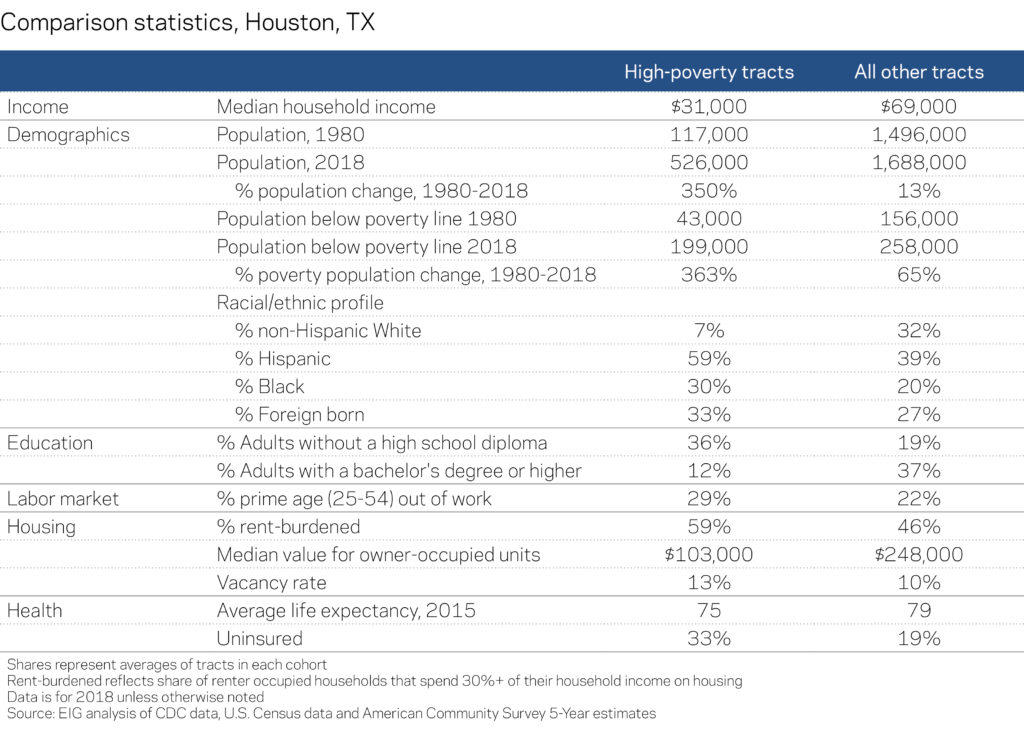

Houston claims the largest number of newly poor neighborhoods in the country after Detroit. Newly poor neighborhoods far outweigh the city’s persistently poor or deepening poverty neighborhoods. City-wide, the poverty rate rose from 13 percent in 1980 to 20 percent in 2018. The city now has nearly half a million people living below the poverty line.

Houston’s historically impoverished neighborhoods, like its Fifth Ward, are mostly clustered around downtown. Houston’s downtown itself has revitalized, but poverty rates remain quite high to the north and west of it. In contrast to many Rust Belt cities, where poverty tends to spread from urban cores to adjacent suburban tracts over time, pockets of high poverty in Houston have leapfrogged many prosperous and middle class neighborhoods to take root on the far edges of the city. Neighborhoods more than 15 miles from downtown Houston are now experiencing climbing poverty rates.

The consequence of this unique spread of high-poverty neighborhoods is that economic well-being is now highly stratified on hyper-local scales. Neighborhoods right next to each other differ starkly. About 10 miles west of downtown, Houston’s Gulfton neighborhood has experienced a precipitous decline since 1980, when it provided housing for predominantly white workers in Houston’s oil industry. The neighborhood now serves as a gateway district for Hispanic immigrants. It faces compounded economic and demographic challenges: 52 percent of its residents do not have a high school diploma, its median family income is $23K, 60 percent of residents are rent-burdened, and the neighborhood’s poverty rate climbed from 12 percent in 1980 to 41 percent in 2018.

Immediately adjacent to it is Bellaire, a municipality carved out of Houston proper. One neighborhood in Bellaire across the highway from Gulfton has a poverty rate of just 1.8 percent and more of its population (84 percent) has a bachelor’s degree or higher than has a high school diploma in Gulfton. The median family income exceeds $250,000. These two neighborhoods demonstrate a new pattern in the geography of inequality within American cities where high-poverty neighborhoods form right next to low-poverty neighborhoods, a pattern that is especially common in other sprawling, fast-growing cities such as Phoenix and Charlotte.

The Hispanic population in Houston’s high-poverty neighborhoods has increased dramatically over the past 38 years, rising from 18,000 in 1980 to 330,000 in 2018. Its high-poverty Black population also climbed from 92,000 to 140,000, and the non-Hispanic white population in high-poverty neighborhoods rose from 4,600 in 1980 to 36,000 in 2018. Corresponding to the city’s growth in Hispanics living in high-poverty neighborhoods, the number of immigrants living in high-poverty neighborhoods increased from 8,900 in 1980 to 192,000 in 2018. Immigrants now make up one-third of the population of Houston’s high-poverty neighborhoods. However, like most other cities, immigrants below the poverty line are not much more likely to end up in a high-poverty neighborhood than native-born residents. Forty-five percent of Houston’s poor immigrants live in a high-poverty neighborhood, compared to 43 percent of poor native-born residents. At the same time, Houston’s high-poverty neighborhoods face unique challenges compared to other cities. Among major cities, residents of its high-poverty neighborhoods are the least likely to have health insurance.