Advancing Economic Development in Persistent-Poverty Communities

Advancing Economic Development in Persistent-Poverty Communities

Overview

Once a thriving industrial metropolis, the St. Louis region struggles with slow growth and a long history of racial divides. The persistently poor group of census tracts centered around North St. Louis struggles under the weight of depopulation and decades of private disinvestment. This quadrant of the city is representative of the Black urban poverty that was seeded decades ago by deindustrialization, suburbanization, and discriminatory housing policies all across the Rust Belt. Revitalization is made all the more challenging by local government fragmentation, which, combined with such depopulation, has left many municipalities with depleted local tax bases and few resources to invest in themselves. Fragmentation extends to the civic sector, too, where community development organizations proliferate but achieve less separately than they could together.

Today, North St. Louis remains a stone’s throw from economic opportunity in the city’s flourishing central corridor and western suburbs, but residents expressed the feeling that their neighborhoods’ fates were nearly completely cut off from those of the broader regional economy, so deep are the divides across all facets of economic and social life in the region. Leaders recognize that repairing that civic fabric is a top priority. New initiatives to cultivate local suppliers and contractors, stabilize communities by improving schools and building out from neighborhood cores, and intentionally marry advanced manufacturing with inclusive development hold promise, but decades of divides and mistrust have left even cautiously optimistic residents waiting to see results.

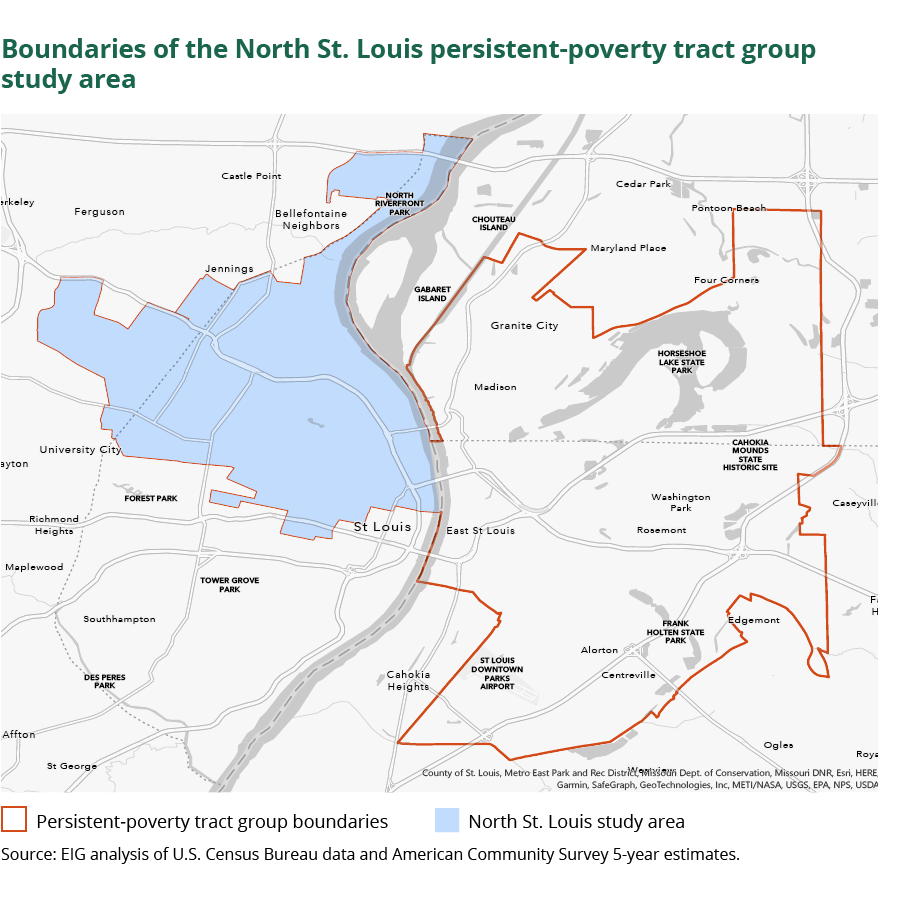

Geography and background

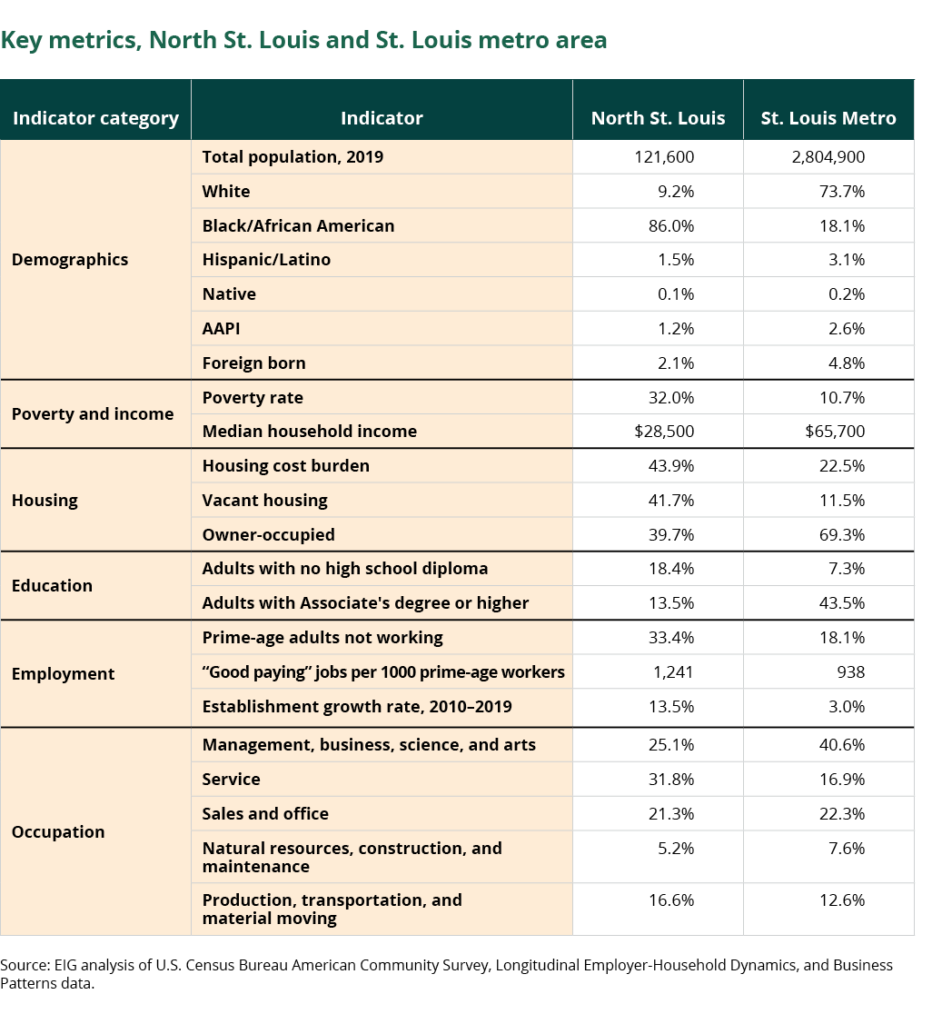

The City of St. Louis, which is separate from St. Louis County and has county-equivalent status, is itself considered a persistently poor county, with a poverty rate of 21.8 percent in 2019 (compared to 9.7 percent for St. Louis County). However, a more granular look at the census tract level provides a very different picture of the geography of local poverty. In reality, the region hosts a continuous expanse of persistent neighborhood poverty forming a single PPTG encompassing 75 census tracts stretching from inner-ring St. Louis County suburbs to the west and north, through the city, and all the way across the Mississippi River to East St. Louis, Illinois. Altogether nearly 200,000 people (62,000 below the poverty line themselves) live in this PPTG—one of the nation’s largest. Our study focuses on the Missouri portions of this cluster, which includes the historically marginalized neighborhoods north of the “Delmar Divide,” referring to the east-west Delmar Boulevard which divides the city by race and class. The core of the study area rests within the bounds of the City of St. Louis, where poverty has persisted the longest, but many challenges are shared with neighboring communities in north St. Louis County, just over the municipal boundary.

In our focus groups and interviews, St. Louisans themselves readily pointed to how such divides define their city. More than perhaps any other city in the United States, St. Louis’s history blends that of the industrial north with the formerly slave-holding south. Long before the so-called “Great Migration” sent millions of Black people from southern states to northern ones in search of industry and opportunity, St. Louis had an established, stable, and segregated Black community. As the city industrialized and the automotive, aerospace, and other manufacturing industries flourished in the post-World War II-era, so did the Black middle class, centered around North St. Louis.[1]

However, deindustrialization also took hold early and swiftly in St. Louis, and the mid-century wave of suburbanization crashed across an already-segregated map.[2] As urban conditions deteriorated, the sequential blows of white flight, Black middle-class flight, and then the flight of most remaining households with the means to get out exacerbated the decline of North St. Louis. The result was massive disinvestment from once-stable, majority-Black neighborhoods.[3] The city’s population has more than halved since 1950, while that of the surrounding county has doubled, testifying to the zero-sum nature of intra-metro migration in the segregated and jurisdictionally-fractured region. Racial undercurrents lie beneath such a seismic regional reallocation of residents: the white share of the city’s population fell from 82 percent in 1950 to 43 percent in 2018.[4] Today, St. Louis ranks as the 10th most segregated large metropolitan area in the country, similar to peer cities such as Buffalo, Cleveland, and Philadelphia.[5] Black residents in the city are three times more likely to live in concentrated poverty than whites.[6] In the North St. Louis study area, Blacks encompass 86 percent of the population compared to only 18 percent in the metro area.

The segregation and clustering of high-poverty, majority-Black neighborhoods make St. Louis demonstrative of the Black Urban typology of persistently poor areas discussed in various sections of this report. Since the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson in 2014, communities in the region have been immersed in conversations about racial injustice and have progressed further along the journey of racial reckoning than many others. The Ferguson Commission, appointed by former Missouri Governor Jay Nixon in 2014, examined how “systemic racism” embedded in the history of local and national institutions has disproportionately segregated Black communities from access to opportunity and caused disparities in everyday life.[7] Regional economic development entities have since developed roadmaps for advancing racially and spatially inclusive economic growth in the region.[8] However, leaders and residents alike share the sentiment that with plans galore, now is the time for action.

Key challenges and barriers to revitalization

Despite the region’s slow growth, lack of quality jobs is not the core problem facing North St. Louis, which lies in close physical proximity to downtown and numerous anchor institutions—as do many other persistent-poverty tract groups located inside metropolitan areas across the country. Instead, the quadrant of the city faces a series of stacked issues: getting residents into those jobs, helping residents keep those jobs, helping neighborhoods then keep those workers, and helping neighborhoods attract businesses. Thus, workforce development and educational attainment strategies are essential for breaking cycles of poverty and boosting the incomes of North St. Louis residents at the individual level, but economic development efforts also need to work on the physical development of the area and the fundamental economic conditions of North St. Louis itself. If the quality of the location does not improve, residents who attain good jobs will likely continue to move away and leave the area in persistent poverty. To truly turn around, North St. Louis needs to be reintegrated into the economic fabric of the region.

Stark population decline makes it challenging to maintain a sustainable level of economic activity in North St. Louis

In urban areas, a certain level of population and housing density is key to the revitalization of communities. Yet, the population of North St. Louis fell by 40 percent from 202,000 in 1990 to 122,000 in 2019, while that of the exurban counties in the metropolitan area jumped by 39 percent from around 300,000 to 418,000. This intra-metropolitan redistribution of population out of persistently poor communities presents one of the most formidable headwinds confronting the revitalization of the affected neighborhoods as households with means leave for communities that offer more safety, better schools, higher-quality services, and more stable home values. The continued drip of residents and activity from the area weighs on its economic prospects—few want to invest in an area with a shrinking consumer base.

Such depopulation has also left this once-urbanized area surprisingly low-density, which presents another hurdle to revitalization. With residential and economic activity so attenuated, there are too few neighborhood poles around which to anchor revitalization. New investment gets diluted or spread too thinly to achieve a critical mass of economic momentum that might catalyze a self-sustaining turnaround. One initially promising attempt demonstrates the challenge: the 14th St. Mall in Old North St. Louis was redeveloped by the City of St. Louis and community-based organizations between 2007 and 2010.[9] The revitalization project was initially hailed as a success as it temporarily halted population decline and attracted a wave of new residents and small businesses to the neighborhood’s historic commercial corridor itself.[10] But the upswing did not last. Eventually, depopulation resumed, and few small businesses found they could succeed with so few people living, working, and spending in the community.

Relatively unique among major metropolitan areas is St. Louis’ undersized immigrant population, at just under 5 percent. The lack of immigration from abroad contributes to the city’s low headline population growth rate. Low rates of international immigration may inhibit the region’s poor neighborhoods from turning around, too, as recent immigrants often seek out affordable neighborhoods and do not view local real estate markets with the same prejudices as long-term residents. Bolstering immigration could help backfill neighborhoods on the losing side of intra-metropolitan migration and blunt the zero-sum nature of population dynamics in the region.

Multiple factors inhibit demand to live and work in the area

North St. Louis suffers from traditional market mechanisms having broken down. Demand to live or do business in the area is too low. Normally, economies have the ability to self-correct. But in the case of North St. Louis, so much land is held by private speculators or in trust by the public sector in a complex patchwork that the market struggles to clear. Consequently, the area struggles to reactivate and redeploy its assets. Issues around vacancy, aging infrastructure, poor public services, and safety all compound the underlying problem that this urban area has undergone extreme disinvestment from which it is very difficult to recover.

Decline, once it sets in, has its own momentum. As middle-income and working-class families move out of North St. Louis and adjacent communities, municipal governments and public schools struggle to provide quality services to remaining residents.[11] This struggle then sets off a cycle that leads to more population loss, as poor schools and services drive out more residents.[12] Crime is perpetually on the mind of residents and in the prejudices of others in the region. In focus groups, residents complained of poorly maintained roadways and dilapidated public spaces as factors that keep people away. Residents were especially impatient with poor services in the City of St. Louis itself, where sufficient resources should be available to pick up the trash on time and keep the streetlights on.

Low-quality public services and schools contribute to the broader devaluation of properties in the neighborhood and stand in the way of attracting new residents. Meanwhile, old and abandoned buildings drive down property values and neighborhood quality. Fully 42 percent of the study area’s housing stock is vacant, some of the highest rates of any neighborhoods in the country—and that figure excludes the extensive demolitions that have turned entire blocks green. Attesting to the extent to which market demand for land and property in North St. Louis has all but dried up, one interviewee mentioned that some of the properties fail to get even $5,000 at auction.

Because the neighborhoods are perceived as a poor store of value, it has been extremely difficult to get bank lending to open a business or renovate a house or commercial property in North St. Louis. The city’s out-of-date zoning code, which has not been updated since 1947, makes attracting private investments to fuel the economic reinvention of the neighborhood even more challenging.[13] Many blocks—and sometimes several adjacent ones—that were once residential are now completely empty, with all prior structures demolished. Yet rezoning and repurposing such parcels on a plot-by-plot basis is costly, time-consuming, and uncertain—adding more barriers to redevelopment in an area that is already at a disadvantage relative to other parts of the region.

Thus, a key challenge facing North St. Louis is how to improve livability in the face of so many headwinds. With such limited demand, the area demonstrates the clear usefulness of a tool such as Opportunity Zones in principle. The federal investor tax incentive is designed to increase investor interest in particular areas by raising the potential returns they can look forward to if their investments are successful. However, such an incentive alone appears unable to move the dial significantly in a place with as many compounding issues as North St. Louis, which has seen little investment through the incentive itself. However, the City Foundry STL, a local Opportunity Zone investment towards the southern edge of the study area, is widely hailed as a community development coup, bridging St. Louis’ divides and supporting minority entrepreneurs from diverse backgrounds.[14] An example of economically inclusive infill development, it may offer a model for other parts of the community, too.

Fragmentation combined with slow growth creates a zero-sum local economic situation

Governance in the St. Louis region is fractured from the highest to lowest levels. The metro area is spread across two states and 15 different counties. The city and county itself are separate entities. The county, for its part, consists of 88 municipalities after a few recent mergers and numerous unincorporated areas.[15] Many municipalities are very small; 21 of them have fewer than 1,000 residents. Meanwhile, the city of 300,000 was divided into 28 wards (nearly one for every 10,000 residents) represented by separate aldermen until the passage of a recent redistricting plan, which will reduce the number of wards in half.[16] By comparison, the city of Washington, DC, consists of only 8 wards for a population of 700,000.

In many ways, the region’s history of divisions by race and class manifest themselves in this fragmented governance of municipalities. Even St. Louis City has a long history of gated communities, special tax districts, and exclusionary zoning. As in metro areas across the country, many suburban municipalities established mid-century were expressly incorporated to keep residents’ tax revenues in while keeping cities’ problems out.[17] Locally, the result is a fractured regional tax base, continuous westward sprawl, and a rolling redistribution of economic activity within a region with slow headline growth.[18]

Fragmentation carries over into the civic sector as well. On the face of it, the region has a robust civic infrastructure: approximately 3,260 charitable organizations serve the St. Louis metro area communities.[19] This robust civic foundation represents a core strength of many of the predominantly Black urban counties and tract groups studied in this project. Many stakeholders stated throughout the interviews that there are many committed, passionate community-based organizations that work to bring positive changes to the region. Yet we also heard that the non-profit landscape is so fragmented that the aggregate impact of the vibrant ecosystem all too often adds up to less than the sum of its parts. In such a fractured landscape, organizations often find themselves competing against each other for scarce funding, duplicating efforts, and struggling individually to achieve scale.

Interviewees also acknowledged that the region needs more capable and effective actors and better policies and practices that encourage collaboration among them. Stakeholders generally agreed that St. Louis had too many, too small local governments and non-profit groups—and felt strongly that their capacity to carry out quality work varied immensely. Too many local governments were an obstacle to reform, rather than a visionary and empowering partner. For some this comes down to limited staff and resources under the tight budgetary constraints imposed by their limited tax bases, but for others it is a matter of capacity, priorities, and culture.[20] Accountability and collaboration are needed to help all the existing pieces in the community fit together better.

Assets and opportunities

Despite significant challenges, the St. Louis metropolitan area is rich in assets, starting with its people and their communities. More than 120,000 individuals reside in North St. Louis city, constituting the bedrock of resilience the community maintains in the face of its challenges. There are numerous opportunities to build on strengths, cultivate new ones, and experiment with new models. The city’s rich base of anchor institutions, civic actors, and leaders across sectors can help provide both the vision and the resources to make transformational change happen. Perhaps most importantly of all, St. Louis is a region aware of its problems. Numerous initiatives are underway to overcome the fragmentation and segregation that has held the region, and its poor communities, back for too long. And through programs like Neighborhood Leadership Fellows, a new generation of leaders is taking the helm.

Overcoming fragmentation

Multiple organizations and initiatives stand out for their innovative approaches to overcoming the barriers presented by fragmentation. Regional leaders recognize that fragmentation is an obstacle to economic development and have been taking steps to find creative solutions around the issue.[21] In 2013, the independent city and county governments merged the business support functions of the two separate agencies—the Economic Council of St. Louis County and the City’s St. Louis Development Corporation—to “more effectively promot[e] business expansion, retention, and job creation” throughout the St. Louis region.[22] As a result, the St. Louis Economic Development Partnership was formed, and it has since assisted the St. Louis City and County business community with development activities such as site selection and preparation, business incubators, and workforce development. The initiative expires in 2023, however, and with a mixed report card locally, its future is uncertain—signifying the practical difficulties inherent in overcoming fragmentation across governments.[23]

Civic leaders are trying to overcome fragmentation as well. For example, in 2021, five leading economic development organizations in the region—AllianceSTL, Arch to Park, Civic Progress, Downtown STL, Inc., and the St. Louis Regional Chamber—joined forces into Greater St. Louis, Inc., to better coordinate their expertise and resources around a shared vision of advancing a competitive, inclusive economy in the St. Louis region. As the region’s flagship business association, Greater St. Louis, Inc., develops metro-wide economic development strategies together with business and civic leaders, provides capacity-building programs, and advocates for policy priorities that advance broad-based prosperity in the region.

One organization that stands out in particular is Beyond Housing. Through their 24:1 Initiative, the group works across 24 different small municipalities on long-term investment and neighborhood revitalization strategies, replenishing local tax bases, and reaching economies of scale in procuring or providing essential services.[24] Rare in the economic development space is Beyond Housing’s recognition that improving public schools is essential for turning around neighborhoods, given how residential markets work in the United States. Thus, they have organized around a single school district, the Normandy school district in North St. Louis County, bringing different municipal governments and other stakeholders together to maximize the impact and make it sustainable. They have also adopted a multi-pronged approach of trying to broadly stabilize an area while investing in—and building out from—key nodes of activity in the community to improve the quality of residents’ lives.[25]

Boosting connectivity between advanced industries and distressed neighborhoods

Geographically, North St. Louis’ persistently poor communities are close to job centers in downtown and the Central West End, where significant public and private investments have seeded impressive turnarounds and a nation-leading innovation district. St. Louis has an ample base of blue-chip companies and growing advanced industry clusters in life sciences, agriculture technology, and more.[26] Yet, few tangible spillovers from these regional economic development successes have meaningfully materialized for more marginal communities, especially to the north. What is more, since the majority of jobs in the region’s growing advanced industries are knowledge-based, there are few direct pathways to economic opportunity within them for residents of persistently poor areas such as North St. Louis.[27]

In a region as fragmented and divided as St. Louis, focus group participants expressed the sentiment that few benefits from such growth in advanced industries ever reaches them and their communities. There was clear division in our interviews between those who firmly believed that region-wide economic growth and development was an essential if insufficient prerequisite for turning around North St. Louis, and those who felt that economic and social ties were so completely severed that local economic fates were effectively distinct.

The reality is somewhere in between. Slow regional economic growth does present a headwind to community economic development, and stronger growth could make the task of revitalizing persistently poor areas significantly easier. However, it is also true that investment and job growth in the knowledge economy frontier will neither naturally trickle down to the most vulnerable families nor spill over to the most marginalized communities in any meaningful magnitude without intentional efforts to create real, concrete ties in terms of investment and jobs.

The new campus of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) in North St. Louis is a clear case in point of this challenge. One of the biggest investments in the community in decades will eventually employ large numbers of highly-educated workers in advanced fields in a massive but secretive facility that, by its very nature, cannot be well-integrated into the community due to national security concerns.[28] Of course, the facility is still under construction, and it may yet serve as a catalyst. Anecdotal evidence suggests that land values around the complex are rising, implying that it still has the potential to deliver as an economic tentpole by stoking demand to live and work in a long-neglected corner of the region. Nevertheless, this unambiguous win for the regional economy may struggle to fulfill initial promises of serving as a neighborhood anchor and community hub. Such overpromising on what the innovation economy can directly deliver to the most hard-up residents and communities risks eroding trust in a region where it was already in scarce supply.[29]

As it looks forward, St. Louis has the opportunity—and in many ways obligation—to better connect its marginalized and underserved populations, centered on North St. Louis, to the benefits of the burgeoning regional economy. While many strategies are already percolating, in this work the region will find itself at the frontier of local economic development practice nationally. This is a toolkit that is still being assembled—and, auspiciously, a lot of that assembly and experimentation is taking place in St. Louis. Look no further than the St. Louis Development Corporation’s long-awaited Economic Justice Action Plan, a bottom-up roadmap for individual economic empowerment that runs through neighborhoods, rooted in inclusive development, with concrete steps for businesses, residents, public entities, and other stakeholders to take to fundamentally change the city’s economic promise.[30]

Another strategy for increasing the connectivity between regional growth and opportunity in long-disinvested communities is to tap into the purchasing power of the anchor institutions in the region, such as Washington University in St. Louis and BJC Healthcare.

In a promising extension of this practice, Greater St. Louis, Inc.’s recent jobs plan launches a Supply STL initiative to help private businesses, not just the usual “eds and meds” anchor institutions, to provide “a reliable and stable customer base” to fuel the sustainable growth of locally-owned minority businesses.[31] In this work of restoring ties, local civic organizations such as Invest STL and St. Louis Anchor Action Network can play a critical role in identifying and connecting small businesses and local entrepreneurs to large anchor institutions, as well as facilitating investment opportunities for underinvested communities.

Connectivity can be strengthened in both hard and soft ways. Most transit lines currently run from east to west, for example, when north-south links would do more to help struggling residents access jobs in the region’s core.[32] On the softer side, progress in reducing the social distance between someone growing up in North St. Louis and someone working in innovation districts is crucial, even if it may take a long time. This can come from outreach, events and programming, mentorship, partnerships, STEM pathways in school, customized training programs, entrepreneurship training academies, and the sort of active and genuine community engagement that organizations, such as the Cortex Innovation Community and BioSTL, are pioneering.[33]

These ideas and thinking are already well baked in Greater St. Louis, Inc.’s proposal for the U.S. EDA’s Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC), which the region won in September 2022.[34] The award was granted to support region-wide, collaborative efforts to foster inclusive economic growth by leveraging existing regional assets—historical manufacturing base as well as growing bioscience and geospatial clusters—while also addressing past racial and spatial injustice. Particularly, the plan, titled St. Louis Tech Triangle, is inherently spatial and emphasizes the role of community-based organizations, embracing the intent to ensure broad-based opportunities and benefits for residents in North St. Louis City: job and business opportunities targeted for residents and underserved populations; training and apprenticeship opportunities; new spaces for community gathering and services; and streetscape improvements.[35] The proposal put the MLK Innovation Center at its core, with numerous initiatives to ensure that the new advanced manufacturing facilities supported by the grant serve as genuine neighborhood anchors with multiple mutually-reinforcing ties into the surrounding community. With the award of a BBBRC grant, St. Louis earns a “once-in-a-generation” opportunity to advance innovation and inclusion, together and intentionally. There is a palpable sense that now is the time to show what equitable economic growth means in the region. And the initiative heralds a long-awaited shift from planning to implementation in the region.

Conclusion

North St. Louis is a classic example of the predominantly-minority persistent-poverty tract groups that sit at the center of many metropolitan area economies today. In this instance, St. Louis City itself qualifies as a persistently poor county, but, with poor neighborhoods concentrated in the north of the city, the area demonstrates the value of the tract-group approach in very populous metropolitan counties in which poverty and plenty coexist in close proximity. Dramatic depopulation and disinvestment have contributed to a gradual winding down of economic life in many parts of the study area. This leads to many chicken-and-egg dilemmas: How to bring residents back with low-quality schools? How to cultivate small businesses without residents? How to stabilize the tax base without either? In response, stakeholders are cohering around an approach of building out from neighborhood cores, but most neighborhoods are still trying to swim upstream. Notably, with top-line regional economic growth relatively stagnant, the region still engages in a mostly zero-sum redistribution of residents and economic activity from declining areas to growing ones, often on the exurban fringe but, more recently, in the city’s central corridor as well.

Fragmentation is a common theme across political, social, and economic life, and race is often the line on which life fractures. In the face of such multidimensional fragmentation, the concept of connectivity comes to the fore. Advancing economic development in North St. Louis requires cultivating more investment that crosses the “Delmar Divide” into North St. Louis, forging more career pathways for residents into good-paying jobs, fostering productive collaboration and economies of scale across the energetic base of community organizations, and harnessing the power of the region’s formidable base of anchor institutions to stimulate private sector growth in the region’s struggling quadrants.

Notes

- “A Preservation Plan for St. Louis Part I: Historic Contexts, The African American Experience,” City of St. Louis; Cambria, N. et al. “Segregation in St. Louis: Dismantling the Divide,” Washington University in St. Louis, 2018; Abello, Oscar P. “Breaking Through and Breaking Down the Delmar Divide in St. Louis,” Next City, 2019.

- Gordon, Colin. “Segregation and Uneven Development in Greater St. Louis, St. Louis County, and the Ferguson-Florissant School District,” University of Iowa, 2015.

- Baumann, Timothy, Andrew Hurley, and Lori Allen, “Economic Stability and Social Identity: Historic Preservation in Old North St. Louis,” Springer, 2008.

- Rowlands, DW and Tracy Hadden Loh. “Reinvesting in urban cores can revitalize entire regions,” Brookings Institution, 2021.

- Brown University, “Diversity and Disparities Index,” Russell Sage Foundation and the American Communities Project, 2020.

- City of St. Louis. “Fourteenth Street Mall: Overview and amenities,” 2022.

- The Ferguson Commission, “Forward Through Ferguson: A Path Toward Racial Equity,” 2015.

- Furtado, Karishma et al. “The State of Education Reform,” The Ferguson Commission, 2020; Greater St. Louis, Inc. “STL 2030: Jobs Plan,” New Localism Associates.

- “A Preservation Plan for St. Louis Part I: Historic Contexts, The African American Experience,” City of St. Louis.

- Office of Policy Development and Research. “St. Louis, Missouri: Crown Square Historic Rehabilitation in Old North St. Louis,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Furtado, Karishma et al. “The State of Education Reform,” The Ferguson Commission, 2020; Greater St. Louis, Inc. “STL 2030: Jobs Plan,” New Localism Associates.

- Bernhard, Blythe. “From falling enrollment to culture, top challenges for next leader of St. Louis Public Schools,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 2022.

- Bartholomew, Harland. “Comprehensive City Plan: Saint Louis, Missouri,” University of Illinois, 1947; Naffziger, Chris. “In 1947, city planners published a map of obsolete and blighted districts. The effects were disastrous,” St. Louis, 2019.

- Theodos, Brett et al. “An Early Assessment of Opportunity Zones for Equitable Development Projects,” Urban Institute, 2020; Woytus, Amanda. “Advantage Capital launches a new fund to support minority-owned businesses and entrepreneurs of color,” St. Louis Magazine, 2022.

- County of St. Louis, Missouri. “Municipal Boundaries,” Department of Conservation, 2021; “Tiny North County community Vinita Terrace merging into Vinita Park,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 2017.

- Board of Aldermen. “City of St. Louis Redistricting,” St. Louis, Missouri, 2022.

- Huber, Joe. “The History and Possibilities of a St. Louis City-County Reunification,” NextSTL, 2010; Rothstein, Richard. “The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles,” Economic Policy Institute, 2014; Cooperman, Jeannette. “The story of segregation in St. Louis,” St. Louis, 2014; Cambria N. et al. “Segregation in St. Louis: Dismantling the Divide,” Washington University in St. Louis, 2018; Gordon, Colin. “The Urban Crisis in the Gateway City,” St. Louis University Public Law Review, 2013.

- Gordon, Colin. “The Urban Crisis in the Gateway City,” St. Louis University Public Law Review, 2013; Florida, Richard and Patrick Adler. “The patchwork metropolis: The morphology of the divided postindustrial city,” Journal of Urban Affairs, 2018.

- Arena, Olivia and Kathryn Pettit. “Harnessing Civic Tech and Data for Justice in St. Louis,” Urban Institute, 2018.

- EIG interviews and listening sessions, Summer 2022; Missouri Senate Division of Research, “Report of the Interim Committee on Greater St. Louis Regional Emerging Issues,” State of Missouri, 2021; Balko, Radley. “How municipalities in St. Louis County, MO., profit from poverty,” The Washington Post, 2014; “Overcoming the Challenges and Creating a Regional Approach to Policing in St. Louis City and County,” Police Executive Research Forum, 2015.

- Coleman, Denny and Brian Murph. “Economic Development in St. Louis City and St. Louis County,” Better Together, 2014.

- Laws and Lawmaking. “Ordinance 69454: Intergovernmental Cooperation Agreement,” St. Louis, Missouri, 2013.

- Interviews and focus groups, Summer 2022.

- Swanstrom, Todd et al. “Civic Capacity and School/Community Partnerships in a Fragmented Suburban Setting: The Case of 24:1,” Journal of Urban Affairs, 2013.

- Beyond Housing. “A Region is Only as Strong ss All of Its Communities,” 2018.

- Muro, Mark and Yang You. “Superstars, rising stars, and the rest: Pandemic trends and shifts in the geography of tech,” Brookings Institution, 2022; Katz, Bruce and Karen Black. “Cortex Innovation District: A Model for Anchor- led, Inclusive Innovation,” Drexel University, 2020; Donahue, Ryan. “Rethinking Cluster Initiatives: St. Louis, Agriculture Technology,” Brookings Institution, 2018.

- “Building a five-year plan to narrow racial gaps in small business growth in St. Louis,” Next Street, 2022.

- Schlinkmann, Mark. “More delay on bill creating ‘protection’ district around new north St. Louis NGA campus,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 2022.

- This sentiment was expressed by residents in focus groups held Summer 2022.

- Develop St. Louis, “Economic Justice Action Plan,” St. Louis Development Corporation, 2022.

- Greater St. Louis, Inc. “STL 2030: Jobs Plan,” New Localism Associates.

- Kim, Jacob. “In push for the north-south MetroLink line, the route gets some tweaks,” St. Louis Business Journal, 2022.

- “Accelerating Inclusive Economic Growth in St. Louis,” Cortex Innovation Community, 2022; “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” BioSTL: Driving St. Louis Innovation, 2008.

- “Greater St. Louis, Inc.: St. Louis Tech Triangle,” U.S. Economic Development Administration, 2022.

- “St. Louis Tech Triangle: Build Back Better Regional Challenge, Phase 2,” U.S. Economic Development Administration, 2022.

This report was prepared by the Economic Innovation Group using Federal funds under award ED21HDQ3120059 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.