By Daniel Newman and Kenan Fikri

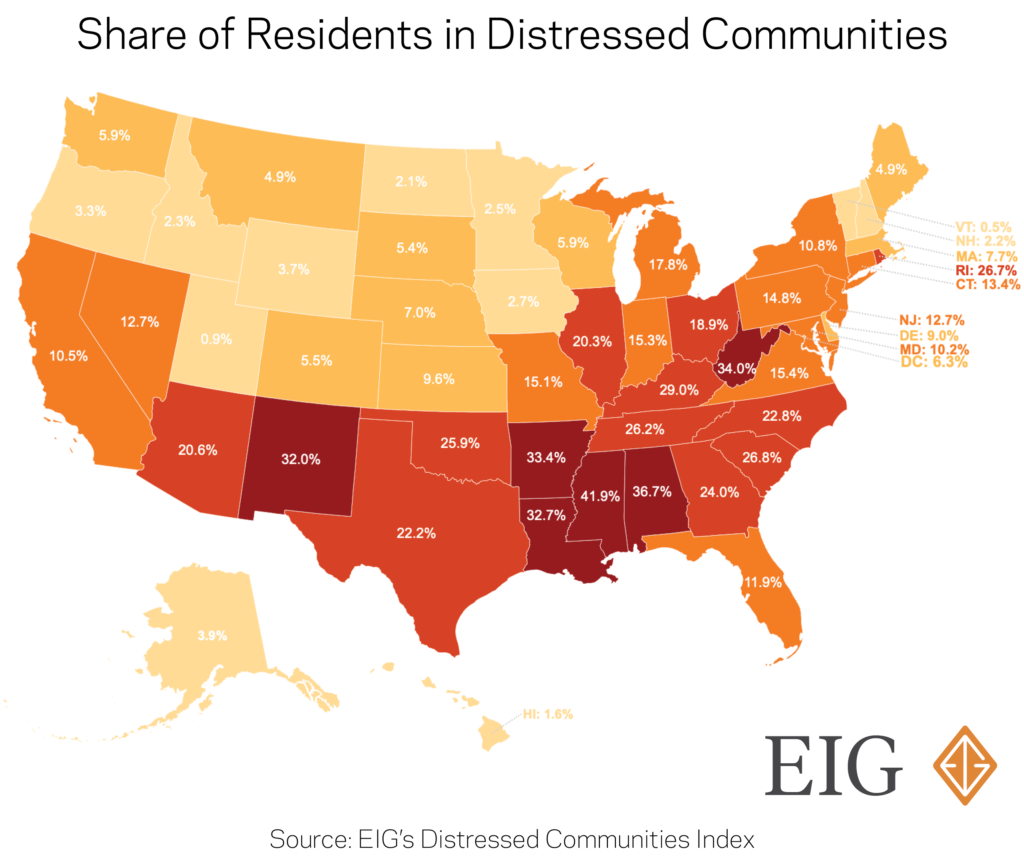

Americans living in distressed communities are about to be hit by a one-two punch from the economic and healthcare crises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Louisiana—where nearly one-third of residents live in an economically struggling community—is now well on its way to being one of the hardest struck by the pandemic. As of Friday, March 27, the state registered 2,305 cases of COVID-19 and 83 deaths. Only New York and Washington have had more fatalities. The vast majority of Louisiana’s counties and parishes have reported cases. On the economic front, unemployment claims shot up to 72,620 last week, the 15th highest in the nation. Louisiana is likely a harbinger for its class of peer states, rather than an anomaly. In Louisiana as well as similarly-distressed Arkansas, Alabama, New Mexico, and West Virginia, cases more than doubled between Monday and Thursday of this week.

In particular, distressed rural areas could face the most difficulty from this unprecedented, multifaceted crisis. Three characteristics prevalent in these communities are poised to make the impact of the new coronavirus and its economic fallout especially acute: large at-risk populations, vulnerable local economies, and weak healthcare infrastructure.

EIG’s Distressed Communities Index (DCI) uses a set of seven indicators to track the socioeconomic health of communities. The DCI illustrates a stark divide between the post-Great Recession economic progress of distressed areas and that of the rest of the country. But the challenges confronting these places are not limited just to the economy; key indicators of physical well-being also lag behind the national average.

What is unique about the health of residents in distressed communities?

The economic divergence between prosperous and distressed communities over the past decade of recovery and expansion is well-documented. The places that have lagged behind tend to suffer from lower rates of labor force participation and educational attainment along with more people in poverty. In distressed communities, the average share of prime-age adults (25 to 54 years old) not working was one-and-a-half times the national rate during the core years of the economic recovery. These communities could be primed to see unemployment rates skyrocket to exceptional levels once again as economic life slows due to the pandemic.

Community economic conditions are strongly linked to individual health outcomes, and there are several ways in which distressed places and the vulnerable populations in them may be disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic:

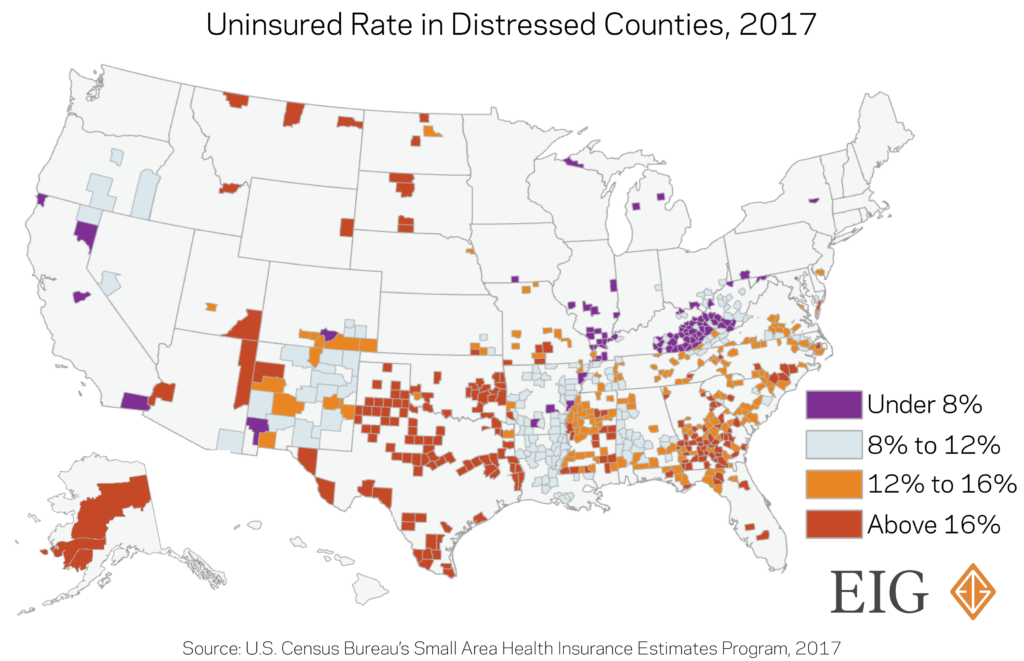

- The uninsured rate for residents of distressed counties is much higher than those living elsewhere. An average of 14 percent of residents were uninsured in the 626 worst-performing (bottom quintile) counties across the United States in 2017. In particular, rural counties with smaller populations tended to have higher uninsured rates. That compares with an average of 8.6 percent of residents lacking health insurance across the top-performing quintile of counties, closely matching the national figure. The difference translates to one out of seven residents lacking coverage in distressed counties versus just one out of 12 residents in prosperous ones.

- Residents of distressed counties are more likely to be elderly and susceptible to complications resulting from coronavirus infection. Four out of every five distressed counties have a larger share of residents over 65 years old than the country overall. That number is startlingly high considering only about half of prosperous counties have a greater percentage of residents age 65 and older than the national figure.

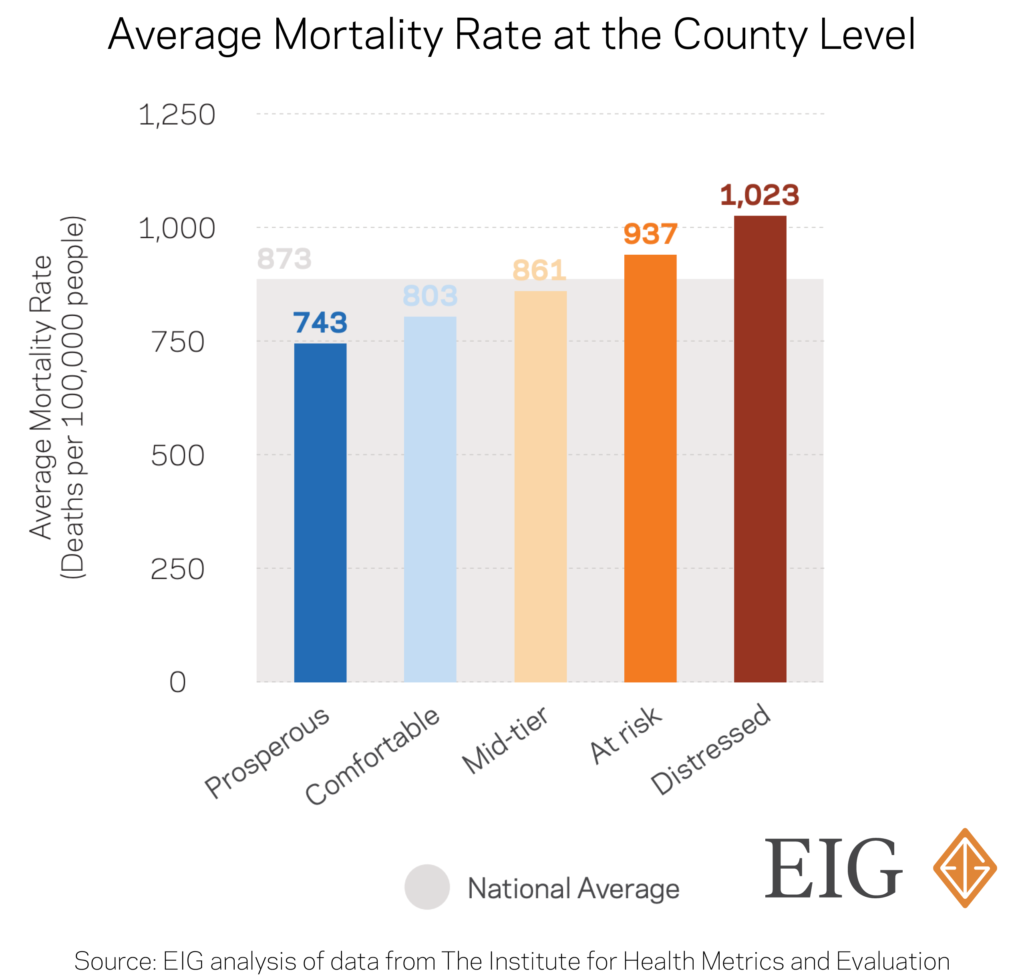

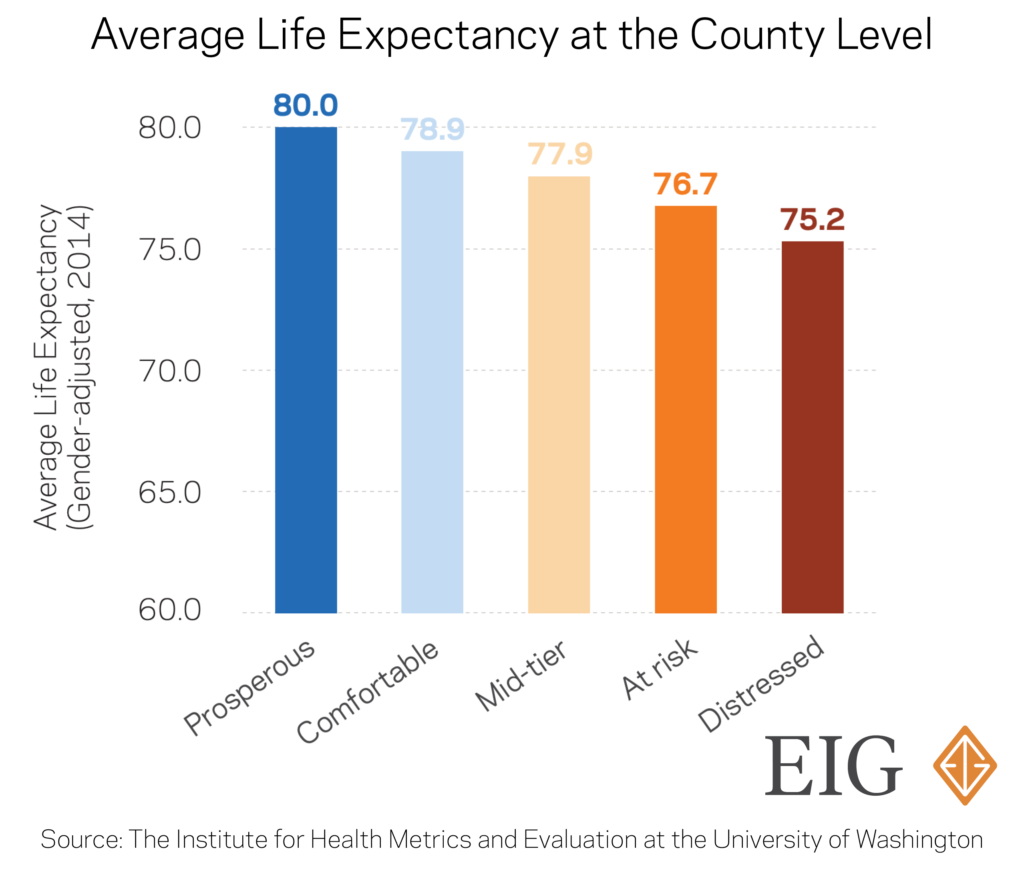

- Life-threatening health disorders are more prevalent and more dangerous in distressed areas. Mortality rates in distressed counties are 25 percent higher than in prosperous ones. The rate of death from cancers, pregnancy complications, suicides, and violence are elevated in these communities. In more rural counties, limited access to quality care exacerbates the situation. Not only can it be more difficult to reach healthcare centers because of physical distance or availability, but once at a healthcare provider, the level of care and availability of treatments can fall below that of more prosperous or urban counterparts.

- Life expectancy is already significantly shorter in economically distressed places. On average, residents of prosperous communities live five years longer than those in distressed areas. The connection between socioeconomic status and life expectancy is unmistakable, and the compounding lack of economic opportunity and weak health infrastructure contributes to the strain in certain communities.

What are the challenges to accessing healthcare in distressed communities?

Access to healthcare–particularly hospital beds vital in an emergency–is now an acute concern as the pandemic spreads across the country, and distressed areas are once again at a disadvantage. It is important to note that nearly 98 percent of distressed counties have fewer than 100,000 people, and 90 percent have fewer than 50,000, making them overwhelmingly rural. The rural healthcare system was already under strain before the current crisis, as 126 rural hospitals have closed over the past decade. These hospitals are often in particularly precarious financial positions, and many have only limited access to specialized services.

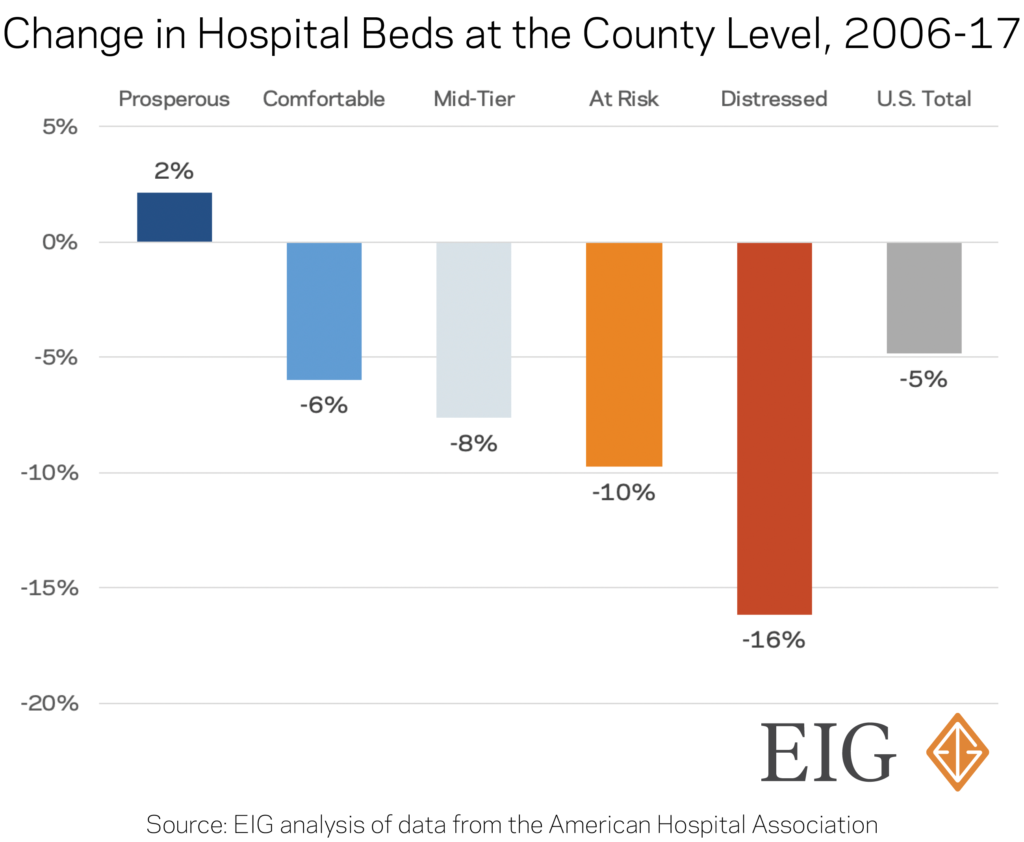

EIG’s analysis of data from the American Hospital Association shows that the number of hospital beds shrank nationwide by five percent from 2006 to 2017 amid a general restructuring of the healthcare industry and a period of hospital consolidations and closures. Indeed, just 16 states recorded a net increase in hospital beds over that time span, many of which tend to have rapidly-expanding populations or serve as retirement hotspots. But the relative availability of beds (number per 1,000 residents) declined in all but six states (AK, AZ, NV, UT, VT, and WA). This standard measure smooths out the effects of population changes over time.

At the county level, only the most prosperous one-fifth of counties recorded any growth in the number of hospital beds, expanding by two percent from 2006 to 2017. Over the same time, distressed counties lost a staggering total of 32,200 beds or about one of every six that had been present in 2006.

What does this all mean for residents in distressed communities?

Many economically left-behind places never fully recovered from the last recession, and they now find themselves on the precipice of being dragged down again. Under threat of a pandemic, these communities must tackle an unprecedented economic crisis from an already weak starting point. If weathering the fallout from an economic shock alone isn’t challenging enough, distressed communities are disproportionately home to elderly citizens and individuals in chronically poor health that face the highest mortality rates from COVID-19 and they will suffer as a result of more limited access to hospital beds than neighbors in prosperous counties. As policymakers seek to counteract the health and economic impacts of the new coronavirus, the unique challenges faced by distressed and rural communities must be front of mind.