By Jason Segedy

Few regions of the United States exemplify what it means to be a legacy place better than Northeast Ohio. This 12-county region, with a population slightly larger than Connecticut and slightly smaller than Oklahoma, was once an exemplar of working class economic prosperity.

This densely-populated region is comprised of four closely-connected core cities—Cleveland, Akron, Canton, and Youngstown—all located within 20 to 50 miles of one another. These cities were globally-significant centers for industrial production, on a truly massive scale that is difficult to even imagine today, in the heavy industries which built the American economy in the 20th century—steel, rubber, tires, automobiles, and machinery.

Since 1970, the region has struggled like few other large metropolitan regions have. While the United States as a whole has increased its population by 64 percent over the past 50 years, Northeast Ohio has lost 7 percent of its population, shrinking from 4.1 million to 3.8 million. Its four core cities, which had a combined peak population of nearly 1.5 million, are home to barely 700,000 people today and are collectively smaller than Cleveland alone was in 1970.

Like the United States as a whole, the region has been transitioning from an industrial, production-based economy to a post-industrial service and consumption-based economy, but at a far slower rate. Once a model of industrial economic prosperity, Northeast Ohio has fallen behind nearly all of the nation’s other large metropolitan areas in terms of median household income and educational attainment. In 1960, median household income in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area was only 9 percent higher than in the Cleveland metropolitan area. Today, median household income in Washington, DC, is 82 percent higher.

Decades after the heavy industries that built this region collapsed, urban and economic policy people still do not have a clear idea of what to do about, or for, Northeast Ohio. The region is still one of the nation’s largest and most urban. It is far less industrial than it once was, but it is still more industrial than most other metropolitan areas, and it is still a place where many people build things and transport things for a living. It has transitioned to a “knowledge-based” economy, in sectors such as “Eds and Meds,” but not as comprehensively or as rapidly as other places.

Today, more and more people across the political spectrum are beginning to ask questions about the nation’s economic policy framework, and about the decisions that have been made in Washington, DC, and on Wall Street over the past several decades, which have had the net effect of concentrating more and more wealth and prosperity in fewer and fewer places.

The previous murmurs of concern and discontent over growing economic disparities between people and places have, now after an economically-crippling pandemic and a contentious presidential election, grown even louder and more urgent.

It is more difficult than ever for someone without a college degree to get ahead economically. Here in Akron, four in five adults do not have a four-year college degree. In Cleveland, Canton, and Youngstown, the number is even lower. Even in the United States as a whole, after decades of transition to a “knowledge economy,” two in three people still do not.

The economic prospects for many in the non-college working class are growing dimmer, and there is little substantive policy discussion about restoring broad-based economic prosperity for working class people.

No demographic group has lost more trust in our political institutions, or has more pessimism about their economic future than people without a four-year college degree.

Perhaps the most profound demographic shift between our recent presidential election and elections in the not-so-recent past was in the realm of educational attainment.

Trump won the vast majority of white, non-college votes, and although non-white, non-college voters still overwhelmingly supported Biden, Trump made historically-significant inroads here as well, to the surprise of many pundits.

As the Wall Street Journal recently reported, the white-collar/blue-collar political divide in this country is deepening. In the 2000 election, Bush won 49 of the most college-educated counties in the United States, while Gore won 51. In 2020, Trump won only 16 of the most college-educated counties, while Biden won 84.

Today, many in the working class are angry and mistrustful. They have borne the brunt of this nation’s social and economic decline, as blue-collar jobs, pay, and benefits have eroded and continue to disappear, and as the once-stable neighborhoods that they call home have continued to decline.

At the same time, many in my own professional class exhibit a startling lack of appreciation for (and increasingly do not possess even a rudimentary understanding of) the jobs, people, and systems that are in place to meet our basic physical needs and which make our civilization and way of life possible.

The aspirations and points of view of people who work with their hands to make things, build things, fix things, transport things, provide food, produce energy, and extract natural resources are increasingly a mystery to those in the professional class.

Many of my fellow “knowledge workers” have the relationship between these jobs and ours backwards. It is these jobs, not ours, that form the base of the pyramid of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. If it wasn’t for these jobs, our jobs would not exist.

This growing class and educational divide was dramatically reflected in the 2020 election results here in Ohio. Despite polls that indicated that the election would be closer this time, Trump (once again) defeated his Democratic opponent by eight points.

For the first time since 1960, and for only the third time since 1892, Ohio did not vote for the winning candidate. What was once the most politically-competitive state in the union is undergoing a seismic political shift.

The Democratic party was once indisputably the standard-bearer for the American working class. But over the past several decades, non-college voters have increasingly shifted toward the Republican party. For the first time in generations, neither party has a lock on the American working class.

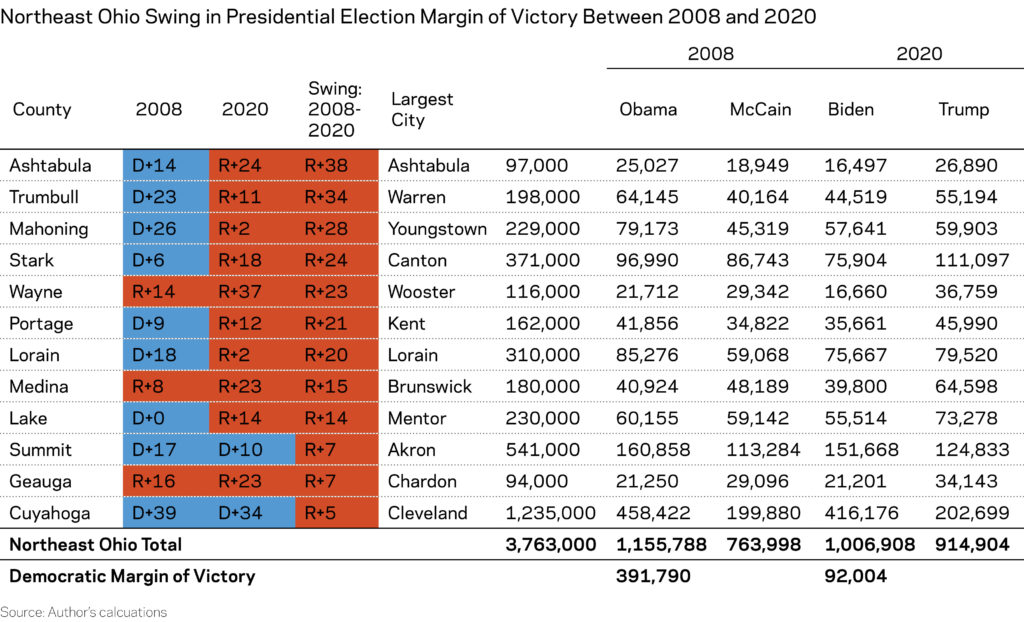

Northeast Ohio has been a stronghold of the Democratic party for decades. The shift in the presidential vote in this region over the past 12 years has been truly profound. I am not aware of another large urban region that shifted more dramatically toward Republicans and away from Democrats between 2008 and 2020.

Every county in the region, including Cuyahoga, which is the most heavily-Democratic county in the state, swung between 5 and 38 points toward Trump.

The three counties along the Pennsylvania border, Ashtabula, Trumbull, and Mahoning, the latter two of which comprise the Youngstown-Warren metro area, and were traditionally the most-reliably Democratic counties in Ohio outside of Cuyahoga County, all swung between 28 and 38 points toward Trump. Trump won all three counties in 2020.

In 2008, Obama won nine of the region’s 12 counties, and carried Northeast Ohio by nearly 392,000 votes. In 2020, Biden won only two of these 12 counties, and carried Northeast Ohio by only 92,000 votes.

We are in the midst of a political realignment in the United States, centered around social class and educational attainment. How extensive and far-reaching that realignment will be is, as yet, unclear.

What is clear is that working class people increasingly feel alienated from the mainstream of both political parties, and are increasingly supporting the populist movements that are embedded within each party.

In the wake of the 2020 election, thoughtful factions within both parties are beginning to discuss pivoting their policy platforms to more intentionally help the working class.

It is unclear to this writer whether the mainstream leadership in either party will do so. But it is equally clear to this writer that leaders in both parties should.

Too many working class people in too many legacy places like Northeast Ohio are being left behind.

In the previous installment of this series, I said that it is time to start helping the people in these places, by helping the places. Northeast Ohio, and legacy places like it, could benefit greatly from place-based approaches to economic development, and from bipartisan public policy proposals that make working class people and places a priority.

Legacy places which still specialize in making and transporting things could be helped by a reevaluation of our national trade and industrial policy; by antitrust reform which would take a hard look at how deregulation has eroded civic assets and strangled lending and capital formation; and by new approaches to urban redevelopment which recognize that legacy city real estate markets don’t look like those in superstar cities. We need to start making more urban policy with cities like Cleveland and Akron in mind, and less with Washington, DC, and San Francisco in mind.

Recently, eight mayors from cities in the Ohio River valley wrote an editorial in the Washington Post, calling for a “Marshall Plan for Middle America.” The plan called for “an ambitious federal response to save our industries and communities from destruction.” The roadmap for the plan discusses a variety of strategies for regional cooperation and federal investment and intervention.

I don’t know enough about the specifics to know whether this is the right approach for the Ohio Valley, or whether the same general concept would make sense for cities in the Great Lakes region, where I live. My sense is that it will need to be fleshed-out further. But the fact that leaders in this part of the country are talking about the collapse of industries and communities in Ohio and in neighboring states, and putting forth bold proposals to do something about it, is a huge step in the right direction, and I commend these mayors for their leadership.

Many commentators in the wake of the 2020 election have said that Ohio is no longer a bellwether. But I wonder about that. Perhaps Ohio is telling the rest of the nation something about our economy and how it has left too many people in too many places behind. Perhaps the rest of the nation should listen.

Jason Segedy is the Economic Innovation Group’s inaugural Legacy Cities Fellow. You can learn more about EIG’s Legacy Cities Fellowship and Jason’s background here.