By: John W. Lettieri, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)1

Chairman Sanders, Ranking Member Graham, and members of the committee: Thank you for the privilege of testifying today on the challenge of inequality in the United States.

My testimony is organized around four distinct aspects of tackling economic inequality and building an economy that supports the needs of all Americans, especially low-income and disadvantaged people. While much of the debate over inequality remains contentious, I believe these four areas provide an opportunity for Congress to work on a broad, bipartisan basis.

- One of the primary ways Americans build wealth is through tax-advantaged retirement savings accounts. Federal policy has failed to support the needs of low- and moderate-income Americans who would benefit the most from opportunities to build wealth. To correct this, Congress should dramatically expand access to proven wealth-building vehicles like the federal Thrift Savings Plan.

- A dynamic economy—one in which entrepreneurialism is encouraged, worker mobility is unrestricted, and technological innovation is embraced—is good for American workers. Restoring the lagging dynamism of the U.S. economy should be a chief priority, starting with restricting the use of noncompete agreements that dampen wage growth and undermine worker well-being.

- The best foundation on which to build policy interventions for low-income and disadvantaged workers is an economy experiencing prolonged and robust economic growth and a tight labor market. As we emerge from the pandemic crisis, it is crucial that we avoid repeating the slow and uneven growth that followed the Great Recession, which had devastating consequences for millions of American workers and families.

- Finally, place matters. Millions of Americans are trapped in persistently high-poverty neighborhoods that exert enormous negative effects on their residents. The number of high-poverty neighborhoods has grown significantly over the past 40 years, and poverty itself has increasingly become spatially concentrated. The United States needs a robust place-based policy agenda to support residents of struggling communities and regions.

The need to help low-income Americans build wealth through long-term savings and investment

The U.S. economy is the world’s most powerful engine of wealth creation and prosperity. In spite of this, the lack of wealth at the bottom remains a troubling and persistent fact of life in this country—one that undermines faith in the basic fairness of our economic system and inhibits the kind of widespread human flourishing to which we aspire as a country.

The numbers are startling: The median net worth for the bottom 25 percent of American families is a mere $310.2 The bottom 50 percent of families own less than 2 percent of total U.S. wealth.3 These statistics are, in part, a reflection of the lack of policies designed to help low-income people build long-term savings and investments.

One of the central reasons for the persistent lack of wealth at the bottom is the lack of adequate retirement savings among low-income families. The median retirement savings balance for the bottom 50 percent of American families is $0. For comparison, the median for families in the top 10 percent is $610,000.4 The glaring failure here is not that affluent Americans are doing well, but rather that current policy is so poorly designed to support those most in need of building wealth.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics,5 access to some form of employer-sponsored retirement plan skews heavily towards higher-income, full-time workers at large firms. Workers in the top quartile of wages are more than twice as likely to have access to such a plan as low-income workers in the bottom 25 percent.

Not only are more affluent workers more likely to have access to a workplace retirement account, but federal tax policy is almost exclusively designed to reward their savings. The reason is simple: tax policy pertaining to retirement savings mostly relies upon deductions from taxable income that are of little use to Americans in the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution, most of whom pay little to no federal income tax to begin with. A person making $20,000 a year and contributing the maximum gets nothing from federal and state tax incentives; a person earning $200,000 gets over $7,000 in federal and state aid. Those needing help creating wealth are implicitly excluded by current incentives.

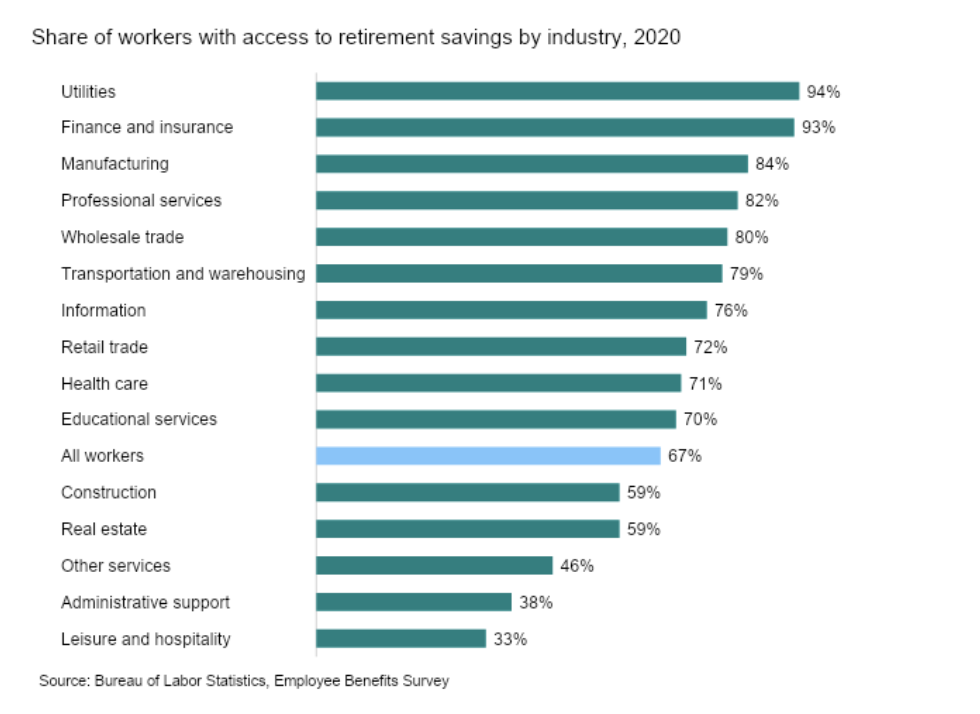

While 67 percent of all private industry workers have access to an employer-provided retirement savings plan, surveys show that only about half of the private sector workforce actually participates in such a plan, down from an estimated 62 percent in 1980.6 These numbers vary dramatically by industry. For instance, in the most pandemic-exposed leisure and hospitality sector, merely one-third of all private sector workers have access to a plan, and only a paltry 16 percent of workers participate in one.7

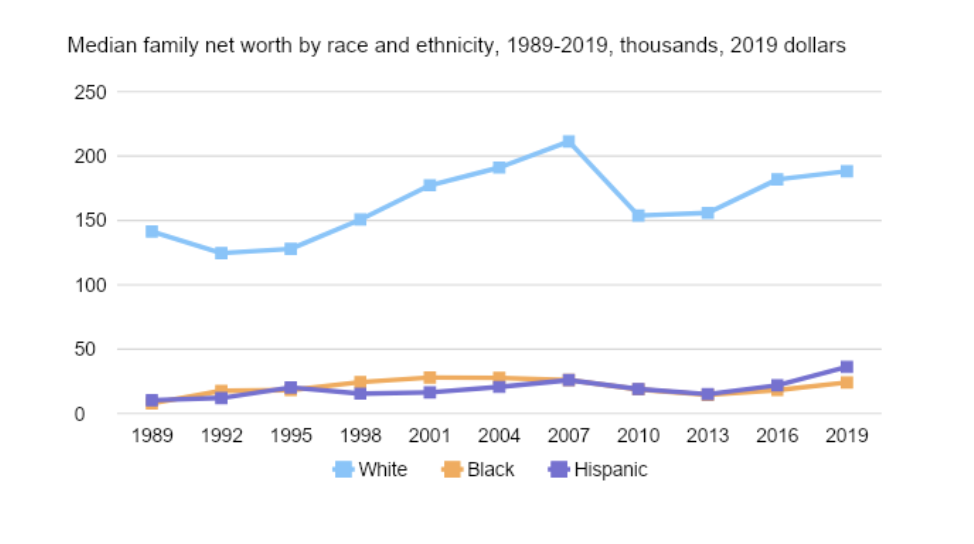

Tackling the deeply uneven participation in retirement savings is also key to addressing the racial wealth gap. According to a study of 2016 data, only 35 percent of Hispanic families and 41 percent of Black families held any retirement account savings, compared to 68 percent of white families.8 Among families that do have at least some retirement savings, the median Hispanic family holds $30,400 and the median Black family holds $35,000, compared to roughly $80,000 for the median white family.9

What can be done? A number of noteworthy proposals, including from members of this committee, have been put forward in recent years to address the dearth of retirement savings among large shares of the population. But there is one option that is both elegant in its simplicity and transformative in its potential benefits—and it will be familiar to every member of Congress: make all low- and moderate-income workers eligible for a program modeled after the federal Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), complete with a government match on contributions up to a certain percentage of income.

The TSP is a defined contribution savings program now available only to federal employees and members of the military. In a paper soon to be published by the Economic Innovation Group (EIG),10 coauthors Dr. Teresa Ghilarducci, a labor economist at the New School and one of the leading experts on retirement security, and Dr. Kevin Hassett, a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution and the former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, make the case for expanding access to the TSP to tens of millions of Americans who currently do not enjoy participation in an employer-sponsored plan. They argue that the design of the TSP makes it an ideal model for helping low- and moderate-income workers build wealth, ensure a comfortable retirement, and grow a nest egg that can be passed on to future generations.

The TSP was first established in 1987 and has evolved over time to incorporate a number of best-practice features that are rooted in the behavioral science on savings. Participants in the TSP—including most members of Congress and congressional staff—enjoy automatic enrollment, a simple menu of investment options, an easy user interface, very low expense ratios, matching contributions by the government of up to 5 percent of income, and a number of other features that, when combined, have proven effective at encouraging remarkably strong participation among eligible workers.

The beauty of the TSP is that it is a proven and carefully studied model that performs exceedingly well for the kinds of traditionally marginalized workers that have largely been neglected by U.S. retirement policy. For example, after the adoption of automatic enrollment, participation among those with a high school degree or less rose to a staggering 95 percent. Likewise, workers in the bottom one-third of earnings also saw their participation rates rise to 95 percent.11Research also finds that workers with low educational attainment and low wages on average contribute a significant share of their earnings to their TSP accounts.12 In other words, TSP already provides compelling evidence that low-income, limited-education workers will avidly participate in well-designed savings schemes made available to them.

Creating a new pathway for working Americans to build wealth through a widely-available and portable program modeled on the TSP would be a transformative step towards ensuring everyone has a meaningful stake in national economic growth and prosperity. Such a program would be in addition to—not in place of—Social Security, filling the gap in current policy to support of tens of millions of workers, including part-time and gig workers, who currently lack access to an employer sponsored plan and for whom current incentives to save do not apply. Early estimates suggest that the enormous social and economic benefits generated by this policy could be achieved at relatively little cost, as the forthcoming paper and subsequent analyses will demonstrate.

I want to close this section with a brief thought on the cost of such a program. Would expanding access to a TSP-style program be prohibitively expensive? The short answer is no. As noted earlier, most of its potential beneficiaries pay little or no federal income tax currently, so the foregone revenue in that respect would be negligible. Most of the cost would come from matching contributions by the government. But it’s important to note that, while such a program would increase spending in a narrow sense, the return on investments in a worker’s retirement accounts are almost certain to exceed the government’s borrowing cost, which, as Ghilarducci and Hassett argue, should improve the long-run fiscal balance as that money is eventually taxed upon withdrawal. Furthermore, boosting wealth through retirement savings means that a worker will be less dependent on public assistance in retirement and more likely to spend money, both of which have positive budgetary implications. All of this is, of course, in addition to the substantial benefits of improving the basic fairness and inclusivity of our economy, which wide access to a TSP-style program would no doubt do.

The benefits of a dynamic economy for worker well-being

Savings and retirement policies are important planks of an agenda to forge a more equitable distribution of wealth and opportunity in the United States, but a challenge of this scale requires much work besides. Another notable area in which Congressional action could yield immediate dividends for American workers is restoring the dynamism of the American economy.

The term “economic dynamism” refers to the rate and direction of change in an economy, or the process by which an economy reallocates its resources to new and productive uses. It traditionally encompasses activities like the rate of new business formation, the frequency of labor market turnover, and the geographic mobility of the workforce. For much of its history, the United States enjoyed the benefits of a young and fast-growing population, high rates of geographic mobility among workers, a fluid labor market, and high rates of business formation. Troublingly, across all of these measures, the United States is a significantly less dynamic economy than it was prior to the turn of the 21st century. This is bad news for American workers.

Workers benefit from an economy in which new firms are generating demand and competition for labor, and workers are moving fluidly in and out of jobs in pursuit of better and better opportunities. A dynamic economy works as a sort of combined safety net and circulatory system, catching displaced workers and pumping them into new attachments in a constant process of allocation and reallocation. This process is especially important in opening up opportunities for those who have the fewest advantages in the form of wealth, social connections, or educational attainment.13 A fluid labor market also supports the crucial spread of know-how and expertise throughout the economy, which contributes to innovation and productivity gains that benefit everyone. And workers who switch jobs frequently—especially early in their careers—tend to experience the strongest wage gains over time.

While there are many factors at work in the decline of American dynamism, I would like to focus on one of the more obvious and pernicious: the proliferation of noncompete agreements. A noncompete agreement generally prohibits an employee from starting or working for a business that competes with his or her employer. One recent study estimated that somewhere between 36 million and 60 million private sector workers are subject to noncompete agreements.14These agreements are not simply reserved for top executives or workers with highly-specialized expertise. In fact, millions of workers earning under $40,000 are bound by a noncompete.15 What is worse, noncompetes are often enforced even in cases when a worker has been laid off through no fault of their own.

The widespread use of noncompetes harms worker well-being and reduces the dynamism of the broader economy. Strict enforcement of noncompetes is associated with reduced job-to-job mobility, lower wages, and weaker rates of firm formation.16 Research suggests that noncompetes exacerbate racial and gender wage gaps by exerting much larger wage effects on female and Black employees than on white men.17 Furthermore, the harmful effects of noncompetes extend far beyond the individual workers bound by them, exerting a chilling effect on the entire labor market.18 Simply put: noncompetes undermine the goal of fostering an equitable and opportunity-rich job market for all Americans.

There is growing momentum behind noncompete reform. Recently, a bipartisan group of lawmakers in the House and Senate introduced the Workforce Mobility Act, which would prohibit the use of noncompetes except in cases involving the sale of a business or dissolution of a partnership. As we search immediate ways to advance the well-being of American workers, freeing them to benefit from robust and fair competition for their own labor seems a natural place to start. I strongly urge members of this committee to support this legislation, which would help boost wages, strengthen market competition, increase entrepreneurship, and foster a more innovative economy.

The importance of a tight labor market for low-income workers

One of the most important lessons of the past decade is the importance of a tight labor market for low-wage workers. From February 2019 to February 2020, the United States experienced an unbroken stretch during which the unemployment rate remained at or below 3.8 percent, reaching 3.5 percent in November 2019—the lowest level on record since 1969.19 There is growing evidence that tight labor markets deliver disproportionate benefits to workers at the bottom by boosting wages and drawing workers back into the labor market. Sure enough, by the end of the 2010s, prime-age labor force participation was spiking and wages were rising fastest for lower-wage workers.20 In some places, these gains were boosted further by increases in the state and local minimum wage.21

Two things are worth noting. First, many experts believed that such a healthy labor market was out of the country’s reach. For much of the weak and uneven recovery that followed the Great Recession, the idea of a 3.5 percent unemployment rate—without a corresponding spike in inflation—was generally not treated as a serious or achievable policy goal. Theories proliferated to explain why workforce participation remained so low and why meaningful wage growth failed to materialize, including advances in the quality of video games and the idea of a so-called “skills gap.” Only a handful of economists correctly gauged the simple answer to the supposed puzzle of missing wage growth: too much slack.22 By the end of the expansion, demand from a tight labor market was powerful enough to boost wages and pull large numbers of marginally attached workers, video games and all, off of the sidelines.

Second, it was likely to get even better. For all the progress that was made prior to the pandemic, the economy had not yet reached full employment. Absent the crisis, there is reason to believe American workers—including and especially low-wage workers—would have seen a continued period of strong wage growth and widespread economic opportunity. Furthermore, these gains were occurring without major advances in productivity; a tight labor market combined with strong productivity gains would have likely delivered even stronger benefits to workers at the bottom.

The lesson in all of this is that getting to full employment quickly and staying there as long as possible should be a central goal for policymakers as the country exits the current crisis. While redistributive policy interventions can no doubt help address the challenge of inequality, we need to ensure markets themselves are doing “pre-distributive” heavy lifting to support a rising floor of well-being for those at the bottom.23 Tight labor markets are essential for reducing inequality and bolstering workers’ confidence in the broader economy, which is exactly what was occurring prior to the pandemic. By early 2020, Americans were reporting levels of optimism that were at or near the highest ever recorded on a range of questions, including personal financial security, overall confidence in the economy, and the availability of quality employment opportunities.24

The slow-and-steady recovery that followed the Great Recession was in many ways the result of a tepid policy response—one that had devastating consequences for millions of workers, especially the most disadvantaged. We must not repeat that mistake. Congress should be applauded for its willingness to act boldly thus far in response to the economic fallout from the pandemic, and I urge members of this committee to continue doing everything possible to foster a strong, sustained, and widely-felt recovery in the year ahead.

Addressing the challenge of spatial inequality

The final issue I want to address is the role of “place” in the broader landscape of economic inequality.

Spatial inequality, or geographic unevenness in economic well-being, has become an increasingly relevant aspect of the broader debate over inequality in the United States.25 This is because the divergence between thriving and struggling places has grown more pronounced in recent decades, with profound implications for low-income and disadvantaged Americans. As a recent EIG report noted, minorities are especially disadvantaged by deep spatial inequities, and the pandemic has served as a painful reminder that economic, racial, and health inequalities are often spatially concentrated. In the Midwest, for example, fully half of the Black population lives in an economically distressed zip code. In many of these neighborhoods, long and troubled histories of segregation have become entangled with the challenges of post-industrial decline to demonstrate why a place-based policy agenda to restore opportunity must complement efforts aimed at individuals and families, as well.

The spatial concentration of economic distress has a devastating effect on the lives on local residents, especially children. Research finds moving from high-poverty neighborhoods to lower-poverty ones as a child leads to higher average earnings later in life and increases the likelihood of going to college.26 But in general, Americans are moving less and poverty is becoming more spatially concentrated, trapping millions of Americans in environments that make it difficult to achieve the American Dream.

Indeed, like retirement savings, home equity is one of the fundamental ways that people build wealth in this country. Undervalued housing markets and disinvested neighborhoods therefore prevent millions of Americans from building wealth. And since distressed neighborhoods are disproportionately home to minority groups, this lack of housing wealth helps perpetuate the racial wealth gap across generations.

I want to underscore that a growing national economy and rising aggregate prosperity alone are not enough to tackle these deep-seated problems. EIG’s research demonstrates that prosperous areas have captured the lion’s share of new jobs, new businesses, and population growth over the course of the 21st century. Meanwhile, following the devastation of the Great Recession, distressed zip codes—home to over 50 million Americans—continued to see jobs and businesses disappear long after the national economy had turned the corner. Indeed, EIG’s work demonstrates economic distress is “sticky;” it is relatively uncommon for a high-poverty neighborhood to turn around. For example, 64 percent of neighborhoods that were high poverty in 1980 remained high poverty nearly four decades later, while only a small share experienced dramatic improvement. Meanwhile, nearly 4,300 neighborhoods crossed over the high-poverty threshold during that period. By 2018, the United States was home to nearly double the number of high poverty neighborhoods as there were in 1980.27

The persistence and proliferation of crippling community-level economic distress is shameful and exacerbates the already difficult experience of poor and disadvantaged people in this country. While some gaps in well-being between places are natural and benign, we should not be content with an economy in which a large share of communities, home to tens of millions of Americans, experience active decline while the national economy grows larger and more prosperous. This is not inevitable.

EIG recently published a policy roadmap for addressing spatial inequality, covering everything from how to reorganize the federal agencies to support struggling regions, to enacting an ambitious place-based policy agenda that would boost investment in needy places and support the build the local capacities needed to attract and retain the workforce needed for a thriving economy. I will not repeat that full slate of recommendations here, but simply note that there are a number of actionable steps Congress and the Biden Administration could take today that would, if done in tandem, represent a major advance in how we address the needs of Americans who live in struggling areas of the country. Such place-centric efforts to revive local and regional economies would complement people-centric policies, like a child allowance, that directly address the material needs of poor and low-income households.

One relatively new policy, Opportunity Zones, holds enormous promise and is already being put to work in communities nationwide to support of a wide-range of needs, including affordable housing, revitalizing blighted business districts, expanding local businesses, and helping formerly incarcerated individuals find high-quality employment. But more should be done to strengthen the policy and ensure it achieves its potential and purpose. For example, Congress should pass the bipartisan IMPACT Act, which would establish thorough reporting and transparency requirements and ensure the policy can be evaluated over time. Congress should also strengthen the incentive itself and make it more useful to a “build back better” agenda in the country’s neediest communities in the wake of the current crisis.

Conclusion

Boosting incomes, wealth, and well-being for those at the bottom is a worthy policy goal that should be tackled from a number of complementary directions.

The challenges I have outlined above are urgent and affect tens of millions of Americans, many of whom have had their lives deeply disrupted by the pandemic and economic crisis. Fortunately, each of these areas is ripe for bipartisan policymaking.

Thank you, and I look forward to taking your questions.

Download the Full Testimony

1Special thanks to my EIG colleagues August Benzow, Kenan Fikri, Catherine Lyons, and Jimmy O’Donnell for their assistance as I prepared this testimony.

2Federal Reserve. 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

3World Inequality Database. Wealth inequality, USA, 1962-2019

4Federal Reserve. 2019 Survey of. Consumer Finances.

5Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey — Benefits 2020.

6Teresa Ghilarducci and Tony James, Rescuing Retirement, 2018.

7Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey — Benefits 2020.

8Monique Morrissey, Economic Policy Institute. The State of American Retirement Savings, 2019.

9Federal Reserve. 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

10The authors’ forthcoming work is discussed here with their permission.

11Justin Falk and Nadia Karamcheva, Congressional Budget Office. The Effect of the Employer Match and Defaults on Federal Workers’ Savings Behavior in the Thrift Savings Plan, 2019.

12Ibid.

13 Steven J. Davis & John Haltiwanger. “Labor Market Fluidity and Economic Performance,” 2014.

14Alexander J.S. Colvin and Heidi Shierholz, Economic Policy Institute. “Noncompete Agreements,” 2015.

15Evan Starr, Economic Innovation Group. “The Use, Abuse, and Enforceability of Non-Compete and No-Poach Agreements,” 2019.

16Ibid.

17Matthew S. Johnson, Kurt Lavetti, and Michael Lipsitz. “The Labor Market Effects of Legal Restrictions on Worker Mobility,” 2019.

18Evan Starr, J.J. Prescott, and Norman Bishara, “Noncompete Agreements in the U.S. Labor Force,” 2020; Evan Starr, Justin Frake, and Rajshree Agarwal, “Mobility Constraint Externalities,” 2019.

19Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Unemployment Rate, 1948-2021.

20St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Prime-age Employment-Population Ratio, 1949-2021.”; Jay Shambaugh and Michael Strain, Brookings Institution and American Enterprise Institute. “The Recovery From The Great Recession: A Long, Evolving Expansion,” 2021.

21Jay Shambaugh and Ryan Nunn, Brookings Institution. “Whose wages are rising and why?” 2020.

22Ozimek, Adam. “Explaining the Wage Growth Mystery.” 2017.

23It is worth noting that, while a tight labor market produces generally positive outcomes across the labor market, the national unemployment rate can mask significant differences among geographic areas and racial groups that call for more targeted policy interventions.

24McCarthy, Justin. “U.S. Economic Confidence at Highest Point Since 2000.” January 23, 2020; Reinhart, R.J. “Record-High Optimism on Personal Finances in U.S.” February 5, 2020.

25The following section draws heavily from a recent EIG report, “Uplifting America’s Left Behind Places: A Roadmap for a More Equitable Economy,” by Kenan Fikri, Daniel Newman, and Kennedy O’Dell.

26Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Lawrence F. Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment.” 2016.

27August Benzow and Kenan Fikri, “The Expanding Geography of Neighborhood Poverty.” Economic Innovation Group, 2020.

By: John W. Lettieri, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)1

Chairman Sanders, Ranking Member Graham, and members of the committee: Thank you for the privilege of testifying today on the challenge of inequality in the United States.

My testimony is organized around four distinct aspects of tackling economic inequality and building an economy that supports the needs of all Americans, especially low-income and disadvantaged people. While much of the debate over inequality remains contentious, I believe these four areas provide an opportunity for Congress to work on a broad, bipartisan basis.

The need to help low-income Americans build wealth through long-term savings and investment

The U.S. economy is the world’s most powerful engine of wealth creation and prosperity. In spite of this, the lack of wealth at the bottom remains a troubling and persistent fact of life in this country—one that undermines faith in the basic fairness of our economic system and inhibits the kind of widespread human flourishing to which we aspire as a country.

The numbers are startling: The median net worth for the bottom 25 percent of American families is a mere $310.2 The bottom 50 percent of families own less than 2 percent of total U.S. wealth.3 These statistics are, in part, a reflection of the lack of policies designed to help low-income people build long-term savings and investments.

One of the central reasons for the persistent lack of wealth at the bottom is the lack of adequate retirement savings among low-income families. The median retirement savings balance for the bottom 50 percent of American families is $0. For comparison, the median for families in the top 10 percent is $610,000.4 The glaring failure here is not that affluent Americans are doing well, but rather that current policy is so poorly designed to support those most in need of building wealth.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics,5 access to some form of employer-sponsored retirement plan skews heavily towards higher-income, full-time workers at large firms. Workers in the top quartile of wages are more than twice as likely to have access to such a plan as low-income workers in the bottom 25 percent.

Not only are more affluent workers more likely to have access to a workplace retirement account, but federal tax policy is almost exclusively designed to reward their savings. The reason is simple: tax policy pertaining to retirement savings mostly relies upon deductions from taxable income that are of little use to Americans in the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution, most of whom pay little to no federal income tax to begin with. A person making $20,000 a year and contributing the maximum gets nothing from federal and state tax incentives; a person earning $200,000 gets over $7,000 in federal and state aid. Those needing help creating wealth are implicitly excluded by current incentives.

While 67 percent of all private industry workers have access to an employer-provided retirement savings plan, surveys show that only about half of the private sector workforce actually participates in such a plan, down from an estimated 62 percent in 1980.6 These numbers vary dramatically by industry. For instance, in the most pandemic-exposed leisure and hospitality sector, merely one-third of all private sector workers have access to a plan, and only a paltry 16 percent of workers participate in one.7

Tackling the deeply uneven participation in retirement savings is also key to addressing the racial wealth gap. According to a study of 2016 data, only 35 percent of Hispanic families and 41 percent of Black families held any retirement account savings, compared to 68 percent of white families.8 Among families that do have at least some retirement savings, the median Hispanic family holds $30,400 and the median Black family holds $35,000, compared to roughly $80,000 for the median white family.9

What can be done? A number of noteworthy proposals, including from members of this committee, have been put forward in recent years to address the dearth of retirement savings among large shares of the population. But there is one option that is both elegant in its simplicity and transformative in its potential benefits—and it will be familiar to every member of Congress: make all low- and moderate-income workers eligible for a program modeled after the federal Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), complete with a government match on contributions up to a certain percentage of income.

The TSP is a defined contribution savings program now available only to federal employees and members of the military. In a paper soon to be published by the Economic Innovation Group (EIG),10 coauthors Dr. Teresa Ghilarducci, a labor economist at the New School and one of the leading experts on retirement security, and Dr. Kevin Hassett, a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution and the former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, make the case for expanding access to the TSP to tens of millions of Americans who currently do not enjoy participation in an employer-sponsored plan. They argue that the design of the TSP makes it an ideal model for helping low- and moderate-income workers build wealth, ensure a comfortable retirement, and grow a nest egg that can be passed on to future generations.

The TSP was first established in 1987 and has evolved over time to incorporate a number of best-practice features that are rooted in the behavioral science on savings. Participants in the TSP—including most members of Congress and congressional staff—enjoy automatic enrollment, a simple menu of investment options, an easy user interface, very low expense ratios, matching contributions by the government of up to 5 percent of income, and a number of other features that, when combined, have proven effective at encouraging remarkably strong participation among eligible workers.

The beauty of the TSP is that it is a proven and carefully studied model that performs exceedingly well for the kinds of traditionally marginalized workers that have largely been neglected by U.S. retirement policy. For example, after the adoption of automatic enrollment, participation among those with a high school degree or less rose to a staggering 95 percent. Likewise, workers in the bottom one-third of earnings also saw their participation rates rise to 95 percent.11Research also finds that workers with low educational attainment and low wages on average contribute a significant share of their earnings to their TSP accounts.12 In other words, TSP already provides compelling evidence that low-income, limited-education workers will avidly participate in well-designed savings schemes made available to them.

Creating a new pathway for working Americans to build wealth through a widely-available and portable program modeled on the TSP would be a transformative step towards ensuring everyone has a meaningful stake in national economic growth and prosperity. Such a program would be in addition to—not in place of—Social Security, filling the gap in current policy to support of tens of millions of workers, including part-time and gig workers, who currently lack access to an employer sponsored plan and for whom current incentives to save do not apply. Early estimates suggest that the enormous social and economic benefits generated by this policy could be achieved at relatively little cost, as the forthcoming paper and subsequent analyses will demonstrate.

I want to close this section with a brief thought on the cost of such a program. Would expanding access to a TSP-style program be prohibitively expensive? The short answer is no. As noted earlier, most of its potential beneficiaries pay little or no federal income tax currently, so the foregone revenue in that respect would be negligible. Most of the cost would come from matching contributions by the government. But it’s important to note that, while such a program would increase spending in a narrow sense, the return on investments in a worker’s retirement accounts are almost certain to exceed the government’s borrowing cost, which, as Ghilarducci and Hassett argue, should improve the long-run fiscal balance as that money is eventually taxed upon withdrawal. Furthermore, boosting wealth through retirement savings means that a worker will be less dependent on public assistance in retirement and more likely to spend money, both of which have positive budgetary implications. All of this is, of course, in addition to the substantial benefits of improving the basic fairness and inclusivity of our economy, which wide access to a TSP-style program would no doubt do.

The benefits of a dynamic economy for worker well-being

Savings and retirement policies are important planks of an agenda to forge a more equitable distribution of wealth and opportunity in the United States, but a challenge of this scale requires much work besides. Another notable area in which Congressional action could yield immediate dividends for American workers is restoring the dynamism of the American economy.

The term “economic dynamism” refers to the rate and direction of change in an economy, or the process by which an economy reallocates its resources to new and productive uses. It traditionally encompasses activities like the rate of new business formation, the frequency of labor market turnover, and the geographic mobility of the workforce. For much of its history, the United States enjoyed the benefits of a young and fast-growing population, high rates of geographic mobility among workers, a fluid labor market, and high rates of business formation. Troublingly, across all of these measures, the United States is a significantly less dynamic economy than it was prior to the turn of the 21st century. This is bad news for American workers.

Workers benefit from an economy in which new firms are generating demand and competition for labor, and workers are moving fluidly in and out of jobs in pursuit of better and better opportunities. A dynamic economy works as a sort of combined safety net and circulatory system, catching displaced workers and pumping them into new attachments in a constant process of allocation and reallocation. This process is especially important in opening up opportunities for those who have the fewest advantages in the form of wealth, social connections, or educational attainment.13 A fluid labor market also supports the crucial spread of know-how and expertise throughout the economy, which contributes to innovation and productivity gains that benefit everyone. And workers who switch jobs frequently—especially early in their careers—tend to experience the strongest wage gains over time.

While there are many factors at work in the decline of American dynamism, I would like to focus on one of the more obvious and pernicious: the proliferation of noncompete agreements. A noncompete agreement generally prohibits an employee from starting or working for a business that competes with his or her employer. One recent study estimated that somewhere between 36 million and 60 million private sector workers are subject to noncompete agreements.14These agreements are not simply reserved for top executives or workers with highly-specialized expertise. In fact, millions of workers earning under $40,000 are bound by a noncompete.15 What is worse, noncompetes are often enforced even in cases when a worker has been laid off through no fault of their own.

The widespread use of noncompetes harms worker well-being and reduces the dynamism of the broader economy. Strict enforcement of noncompetes is associated with reduced job-to-job mobility, lower wages, and weaker rates of firm formation.16 Research suggests that noncompetes exacerbate racial and gender wage gaps by exerting much larger wage effects on female and Black employees than on white men.17 Furthermore, the harmful effects of noncompetes extend far beyond the individual workers bound by them, exerting a chilling effect on the entire labor market.18 Simply put: noncompetes undermine the goal of fostering an equitable and opportunity-rich job market for all Americans.

There is growing momentum behind noncompete reform. Recently, a bipartisan group of lawmakers in the House and Senate introduced the Workforce Mobility Act, which would prohibit the use of noncompetes except in cases involving the sale of a business or dissolution of a partnership. As we search immediate ways to advance the well-being of American workers, freeing them to benefit from robust and fair competition for their own labor seems a natural place to start. I strongly urge members of this committee to support this legislation, which would help boost wages, strengthen market competition, increase entrepreneurship, and foster a more innovative economy.

The importance of a tight labor market for low-income workers

One of the most important lessons of the past decade is the importance of a tight labor market for low-wage workers. From February 2019 to February 2020, the United States experienced an unbroken stretch during which the unemployment rate remained at or below 3.8 percent, reaching 3.5 percent in November 2019—the lowest level on record since 1969.19 There is growing evidence that tight labor markets deliver disproportionate benefits to workers at the bottom by boosting wages and drawing workers back into the labor market. Sure enough, by the end of the 2010s, prime-age labor force participation was spiking and wages were rising fastest for lower-wage workers.20 In some places, these gains were boosted further by increases in the state and local minimum wage.21

Two things are worth noting. First, many experts believed that such a healthy labor market was out of the country’s reach. For much of the weak and uneven recovery that followed the Great Recession, the idea of a 3.5 percent unemployment rate—without a corresponding spike in inflation—was generally not treated as a serious or achievable policy goal. Theories proliferated to explain why workforce participation remained so low and why meaningful wage growth failed to materialize, including advances in the quality of video games and the idea of a so-called “skills gap.” Only a handful of economists correctly gauged the simple answer to the supposed puzzle of missing wage growth: too much slack.22 By the end of the expansion, demand from a tight labor market was powerful enough to boost wages and pull large numbers of marginally attached workers, video games and all, off of the sidelines.

Second, it was likely to get even better. For all the progress that was made prior to the pandemic, the economy had not yet reached full employment. Absent the crisis, there is reason to believe American workers—including and especially low-wage workers—would have seen a continued period of strong wage growth and widespread economic opportunity. Furthermore, these gains were occurring without major advances in productivity; a tight labor market combined with strong productivity gains would have likely delivered even stronger benefits to workers at the bottom.

The lesson in all of this is that getting to full employment quickly and staying there as long as possible should be a central goal for policymakers as the country exits the current crisis. While redistributive policy interventions can no doubt help address the challenge of inequality, we need to ensure markets themselves are doing “pre-distributive” heavy lifting to support a rising floor of well-being for those at the bottom.23 Tight labor markets are essential for reducing inequality and bolstering workers’ confidence in the broader economy, which is exactly what was occurring prior to the pandemic. By early 2020, Americans were reporting levels of optimism that were at or near the highest ever recorded on a range of questions, including personal financial security, overall confidence in the economy, and the availability of quality employment opportunities.24

The slow-and-steady recovery that followed the Great Recession was in many ways the result of a tepid policy response—one that had devastating consequences for millions of workers, especially the most disadvantaged. We must not repeat that mistake. Congress should be applauded for its willingness to act boldly thus far in response to the economic fallout from the pandemic, and I urge members of this committee to continue doing everything possible to foster a strong, sustained, and widely-felt recovery in the year ahead.

Addressing the challenge of spatial inequality

The final issue I want to address is the role of “place” in the broader landscape of economic inequality.

Spatial inequality, or geographic unevenness in economic well-being, has become an increasingly relevant aspect of the broader debate over inequality in the United States.25 This is because the divergence between thriving and struggling places has grown more pronounced in recent decades, with profound implications for low-income and disadvantaged Americans. As a recent EIG report noted, minorities are especially disadvantaged by deep spatial inequities, and the pandemic has served as a painful reminder that economic, racial, and health inequalities are often spatially concentrated. In the Midwest, for example, fully half of the Black population lives in an economically distressed zip code. In many of these neighborhoods, long and troubled histories of segregation have become entangled with the challenges of post-industrial decline to demonstrate why a place-based policy agenda to restore opportunity must complement efforts aimed at individuals and families, as well.

The spatial concentration of economic distress has a devastating effect on the lives on local residents, especially children. Research finds moving from high-poverty neighborhoods to lower-poverty ones as a child leads to higher average earnings later in life and increases the likelihood of going to college.26 But in general, Americans are moving less and poverty is becoming more spatially concentrated, trapping millions of Americans in environments that make it difficult to achieve the American Dream.

Indeed, like retirement savings, home equity is one of the fundamental ways that people build wealth in this country. Undervalued housing markets and disinvested neighborhoods therefore prevent millions of Americans from building wealth. And since distressed neighborhoods are disproportionately home to minority groups, this lack of housing wealth helps perpetuate the racial wealth gap across generations.

I want to underscore that a growing national economy and rising aggregate prosperity alone are not enough to tackle these deep-seated problems. EIG’s research demonstrates that prosperous areas have captured the lion’s share of new jobs, new businesses, and population growth over the course of the 21st century. Meanwhile, following the devastation of the Great Recession, distressed zip codes—home to over 50 million Americans—continued to see jobs and businesses disappear long after the national economy had turned the corner. Indeed, EIG’s work demonstrates economic distress is “sticky;” it is relatively uncommon for a high-poverty neighborhood to turn around. For example, 64 percent of neighborhoods that were high poverty in 1980 remained high poverty nearly four decades later, while only a small share experienced dramatic improvement. Meanwhile, nearly 4,300 neighborhoods crossed over the high-poverty threshold during that period. By 2018, the United States was home to nearly double the number of high poverty neighborhoods as there were in 1980.27

The persistence and proliferation of crippling community-level economic distress is shameful and exacerbates the already difficult experience of poor and disadvantaged people in this country. While some gaps in well-being between places are natural and benign, we should not be content with an economy in which a large share of communities, home to tens of millions of Americans, experience active decline while the national economy grows larger and more prosperous. This is not inevitable.

EIG recently published a policy roadmap for addressing spatial inequality, covering everything from how to reorganize the federal agencies to support struggling regions, to enacting an ambitious place-based policy agenda that would boost investment in needy places and support the build the local capacities needed to attract and retain the workforce needed for a thriving economy. I will not repeat that full slate of recommendations here, but simply note that there are a number of actionable steps Congress and the Biden Administration could take today that would, if done in tandem, represent a major advance in how we address the needs of Americans who live in struggling areas of the country. Such place-centric efforts to revive local and regional economies would complement people-centric policies, like a child allowance, that directly address the material needs of poor and low-income households.

One relatively new policy, Opportunity Zones, holds enormous promise and is already being put to work in communities nationwide to support of a wide-range of needs, including affordable housing, revitalizing blighted business districts, expanding local businesses, and helping formerly incarcerated individuals find high-quality employment. But more should be done to strengthen the policy and ensure it achieves its potential and purpose. For example, Congress should pass the bipartisan IMPACT Act, which would establish thorough reporting and transparency requirements and ensure the policy can be evaluated over time. Congress should also strengthen the incentive itself and make it more useful to a “build back better” agenda in the country’s neediest communities in the wake of the current crisis.

Conclusion

Boosting incomes, wealth, and well-being for those at the bottom is a worthy policy goal that should be tackled from a number of complementary directions.

The challenges I have outlined above are urgent and affect tens of millions of Americans, many of whom have had their lives deeply disrupted by the pandemic and economic crisis. Fortunately, each of these areas is ripe for bipartisan policymaking.

Thank you, and I look forward to taking your questions.

Download the Full Testimony

1Special thanks to my EIG colleagues August Benzow, Kenan Fikri, Catherine Lyons, and Jimmy O’Donnell for their assistance as I prepared this testimony.

2Federal Reserve. 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

3World Inequality Database. Wealth inequality, USA, 1962-2019

4Federal Reserve. 2019 Survey of. Consumer Finances.

5Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey — Benefits 2020.

6Teresa Ghilarducci and Tony James, Rescuing Retirement, 2018.

7Bureau of Labor Statistics. National Compensation Survey — Benefits 2020.

8Monique Morrissey, Economic Policy Institute. The State of American Retirement Savings, 2019.

9Federal Reserve. 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

10The authors’ forthcoming work is discussed here with their permission.

11Justin Falk and Nadia Karamcheva, Congressional Budget Office. The Effect of the Employer Match and Defaults on Federal Workers’ Savings Behavior in the Thrift Savings Plan, 2019.

12Ibid.

13 Steven J. Davis & John Haltiwanger. “Labor Market Fluidity and Economic Performance,” 2014.

14Alexander J.S. Colvin and Heidi Shierholz, Economic Policy Institute. “Noncompete Agreements,” 2015.

15Evan Starr, Economic Innovation Group. “The Use, Abuse, and Enforceability of Non-Compete and No-Poach Agreements,” 2019.

16Ibid.

17Matthew S. Johnson, Kurt Lavetti, and Michael Lipsitz. “The Labor Market Effects of Legal Restrictions on Worker Mobility,” 2019.

18Evan Starr, J.J. Prescott, and Norman Bishara, “Noncompete Agreements in the U.S. Labor Force,” 2020; Evan Starr, Justin Frake, and Rajshree Agarwal, “Mobility Constraint Externalities,” 2019.

19Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Unemployment Rate, 1948-2021.

20St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Prime-age Employment-Population Ratio, 1949-2021.”; Jay Shambaugh and Michael Strain, Brookings Institution and American Enterprise Institute. “The Recovery From The Great Recession: A Long, Evolving Expansion,” 2021.

21Jay Shambaugh and Ryan Nunn, Brookings Institution. “Whose wages are rising and why?” 2020.

22Ozimek, Adam. “Explaining the Wage Growth Mystery.” 2017.

23It is worth noting that, while a tight labor market produces generally positive outcomes across the labor market, the national unemployment rate can mask significant differences among geographic areas and racial groups that call for more targeted policy interventions.

24McCarthy, Justin. “U.S. Economic Confidence at Highest Point Since 2000.” January 23, 2020; Reinhart, R.J. “Record-High Optimism on Personal Finances in U.S.” February 5, 2020.

25The following section draws heavily from a recent EIG report, “Uplifting America’s Left Behind Places: A Roadmap for a More Equitable Economy,” by Kenan Fikri, Daniel Newman, and Kennedy O’Dell.

26Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Lawrence F. Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment.” 2016.

27August Benzow and Kenan Fikri, “The Expanding Geography of Neighborhood Poverty.” Economic Innovation Group, 2020.

Retirement Security| Inclusive Wealth Building Initiative

Related Posts

EIG Letter: DHS Should Revise Proposed H-1B Weighted Lottery to Prioritize Top Talent

Will the New Wave of Place-Based Policy Leave Persistently Poor Areas Behind?

EIG Letter: FTC Should Move to Limit Non-Compete Contracts; Congressional Action Still Needed