A tidal wave of insolvency is about to crash on the American small business community,

and Congress is running out of time to stop it.

By Adam Ozimek and John Lettieri

It is now clear that the coronavirus pandemic will exact a staggering toll on the American economy. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has reportedly warned Congress that unemployment rates – currently near their historical lows – could skyrocket to 20% absent massive federal intervention. Former White House Council of Economic Advisors chair Kevin Hassett believes a global recession is nearly certain to unfold, and expects monthly job losses for March to be among the worst in U.S. history. By any measure, an economy that not long ago had driven Americans’ confidence in the labor market and optimism about their financial security to record highs is about to undergo a massive and potentially catastrophic disruption.

To date, the response from policymakers has primarily centered on ways to provide relief for the millions of individuals likely to be directly harmed by the crisis, including direct cash transfers and extended unemployment benefits. While individual relief is badly needed, it is only part of the equation. The fate of individual workers is tied to the survival of employers over the coming months. Small businesses, which employ nearly half of the American workforce, are particularly vulnerable to a crisis that is likely to cause months of lost revenue for businesses in deeply affected industries such as restaurants and retail, which employ millions of American workers.

The economic damage is already underway. Across the country states and cities are forcing non-essential businesses to close in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus. This action is wise and for the greater good, but will devastate small retailers, restaurants, and other customer-focused businesses. The fragility of these businesses and urgency of intervention should alarm policymakers. According to the JP Morgan Institute, 50% of small businesses have a mere 15 days of cash buffer or less. For those that have already shut down their operations, the clock is ticking. Unless policymakers act, a generation of small businesses, including a cohort of new entrepreneurs just getting their start, will be wiped out. As we saw with the last financial crisis, failure on this scale could cause irreparable damage to the entrepreneurial engine of our country.

Unfinished Business

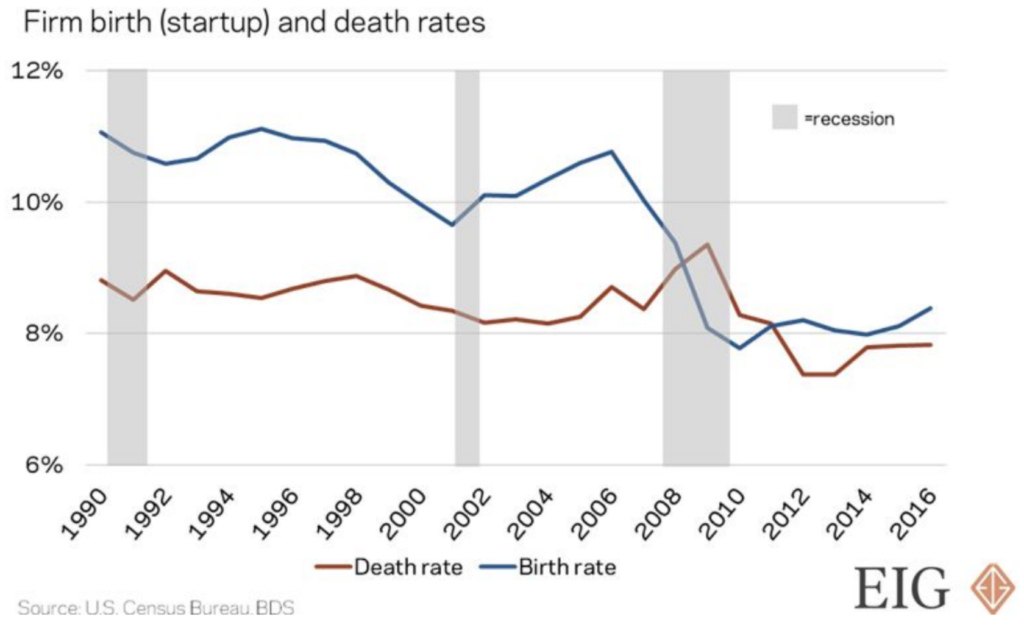

In considering responses to this crisis, policymakers should be mindful of the lingering effects of the last one. The Great Recession marked the first time that U.S. firms were failing at a faster rate than they were being born – a trend that continued for three consecutive years. The financial crisis did severe and lasting damage to American entrepreneurship, driving the U.S. startup rate to its record low. Even after years of subsequent economic expansion, the rate of new business formation remains far below its pre-recession levels. The startup-less recovery revealed one of the glaring failures of the response to the Great Recession. Now, with U.S. entrepreneurship still mired near record low levels, we are facing a certain and dramatic spike in the business death rate, one that will take a disproportionately heavy toll on young firms. Coupled with a predictable drop in new business formation as a result of collapsing consumer demand, the U.S. is once again headed for a severely depressed environment for American entrepreneurship. New businesses that have not had the time to build the cash reserves or establish credit histories that would enable emergency borrowing under normal circumstances are particularly fragile, and should be targeted in any small business relief effort enacted by Congress.

Proposal: Emergency Lending Program for Affected Small Businesses

Small businesses faced with rapid decline in demand will have two fundamental financial challenges: liquidity and solvency. The liquidity challenge is whether they have the money to pay for their ongoing fixed expenses. Businesses that run out of cash will become delinquent on debt and fail to pay rent, and eventually be forced to shut down. However, even small business owners with enough cash in their business or their personal savings to remain operating will face the risk of insolvency, where their business will not be worth operating as the value falls below zero. Unfortunately, the early outline of a White House-backed proposal to provide liquidity to small businesses appears insufficient to alleviate the looming insolvency crisis.

A targeted relief effort must simultaneously deal with the liquidity and solvency problem. To that end, an emergency small business loan program should have the following features:

- Commercial Banks: These loans should be underwritten and held by all commercial banks, so that small businesses can utilize their existing banking relationships or establish new ones. Working with existing lenders will simplify and lower costs for businesses who will refinance existing loans. Banks will be paid by the Federal Government for underwriting, and the government will pay 25 basis points (or whichever rate Congress deems necessary) for the banks to hold the debt on their balance sheets.

- Long-term: Amortization schedules of up to 20 years will allow businesses to spread business cost over a longer period of time.

- Zero Rates: The federal government and banks can currently borrow money at zero or close to zero rates. By insuring these loans under the full faith of the U.S. government, we can pass this low lending rate on to small businesses.

- Uncollateralized: Loans should only be secured by the personal guarantees of the business owners. Businesses in need of emergency lending may lack the collateral necessary for a commercial loan, and assessing collateral quality would waste valuable time.

- Three Months No Payment: Small business commercial loans often include interest only periods, which in the case of 0% interest will mean no payment. This should start with a three month period, which the government can increase if the length of the crisis is longer than anticipated.

- Qualifying Businesses: Providing timely relief to affected businesses will require simple eligibility criteria and a straightforward process for accessing the loans. Lending should be limited to privately-held businesses across all sectors with under 500 full time employees who can demonstrate lost monthly revenue of 25% or more. (Congress may instead choose to focus this program only on sectors likely to experience the most severe effects of the crisis.) To expedite underwriting, no proof of lost revenue will be required up front. However, documentation of temporary significant loss of business revenue must be provided to the IRS as part of the 2021 tax season. Those unable to document this loss will have their loan increased to prime lending rates.

- Broad Usage: Allowed usage of the debt should include maintaining payrolls, refinancing existing loans, purchasing equipment, inventory, furniture and fixtures, funding tenant improvements, and paying for occupied real estate.

- Loan Limits: Loan size should be limited to the lesser of $5 million or 200% of 2019 annual expenses. For the sake of speedy approvals, only the $5 million limit will be imposed up-front and the 200% of annual expenditures will be verified later as part of the business’s annual tax returns. Loans above the 200% of expenditure limit will have the interest rate increased to prime lending rates.

- Bank Liability: For loans amounts above $250,000, if the ex post tax filing fails to substantiate that the recipient business experienced significant revenue loss or finds that it borrowed above the lending limit, banks would see their federal government insurance coverage fall to 90%. This provides skin in the game for banks to provide some due diligence on larger loans, without risking the feasibility of smaller loans. Importantly, both tests are done later so that this does not increase the underwriting burden.

Altogether, this loan program will help to lower business operating costs in a variety of ways. A typical restaurant, for example, will be able to refinance their existing debt, reducing payments for the next three months to zero and to a low level after that. In addition, they may purchase new equipment, buy property they currently rent, pay for ongoing services, and keep crucial staff on payrolls. This will not only help improve cash flow, including potentially zero rent and debt payments in the short-term, but will help to sustain the value of the business and ensure fewer small businesses owners shut down due to insolvency. Instead of a bankrupt business and ruined credit, business owners will have a sound basis from which to invest and expand when the economy is ready. Indeed, a well-designed policy will not only ensure that otherwise viable businesses survive the near-term disruption, but that they also emerge ready to drive a rapid, bottom-up Main Street recovery.

It’s worth underscoring that this program is not “free money” cash assistance, but rather debt provided on terms favorable enough to bolster the resiliency of affected businesses during the worst of the crisis. And, in spite of those generous terms, business owners who don’t believe they stand a reasonable chance of surviving the crisis – and those who were on their way to failure before the recent turmoil – will be unlikely to take advantage of the program. In that sense it is likely to be naturally targeted to the intended recipients: small businesses that are both viable in the medium-term and vulnerable to short-term failure due to the unique nature of this economic shock.

Time Is of the Essence

Every aspect of the federal response thus far has been too slow and too small. Without swift and decisive action, a tidal wave of closures will hit the small business community and unleash far-reaching consequences throughout the economy that may be difficult to undo. This crisis necessitates sacrificing finely-tuned targeting and administrative complexity in favor of broad and immediate accessibility of capital. The potential costs of overreacting – providing stimulus that is too broad or too large – pale in comparison to the potentially devastating costs of underreacting or moving too slowly.

Under normal circumstances, government preventing business from failing is antithetical to the principles of a free market. These are far from normal circumstances. The small businesses facing collapse today did not create the crisis unfolding in our economy, and their vulnerability stems from an exogenous shock they were powerless to avoid. Instead, many are shutting down – voluntarily in some cases, and by order of state and local governments in others – as a once-in-a-generation emergency measure to help us all avoid a far worse fate. While it is necessary that businesses do their part to halt the pandemic’s spread, it is neither fair nor in the public interest to allow mass business failures as a result.

The economy is unlikely to rebound quickly once this emergency has passed if hundreds of thousands of small businesses have permanently shuttered. The millions of people they employ and the customers they serve represent the kinds of relationships that take time to build, and cannot be replaced quickly. If we have learned one lesson from the Great Recession, it is that building new businesses and employer-employee matches after a crash can take a decade or more.

John Lettieri is Co-founder, President, and CEO of the Economic Innovation Group. Dr. Adam Ozimek is the Chief Economist at Upwork. He is also a member of EIG’s Economic Advisory Board.