April 5, 2017: John W Lettieri, Economic Innovation Group

*Watch the full hearing here.

Introduction

Chairman Tiberi, Ranking Member Heinrich, Vice Chairman Lee, and members of the committee: Thank you for the opportunity to testify today.

Many ingredients that helped the United States forge the world’s leading economy over the past century are now the subject of considerable political debate and anxiety — from international trade and investment, to advanced technology, to robust immigration, to even capitalism itself. But one thing that still seems to unite all sides is the shared belief that the United States should be a country in which access to opportunity is broadly available — not simply reserved for those who won the lottery of birth. This idea is at the very core of our national identity.

While there are many ways to approach a discussion on economic opportunity, my testimony today will focus on the pervasive decline of U.S. dynamism and its implications for workers, markets, and regions.

Why focus here? Because a less dynamic economy is one likely to offer fewer pathways to achieving the American Dream. For workers, declining dynamism means fewer labor market opportunities and less upward mobility. For markets, it has corresponded with an era of diminished competition and greater rewards to entrenched incumbents. For regions, it means shrinking industrial bases and more profound geographic disparities.

I especially want to emphasize that the challenges we face related to economic dynamism are new, having emerged clearly in the early 2000s and then accelerated sharply with the onset of the Great Recession. The trends and consequences described later in my testimony put our economy — and, therefore, our policymaking efforts — in uncharted waters. We do not have a playbook for the current status quo.

In short, the central economic challenge of our time is not the trade deficit, tax rates, or income inequality. It’s dynamism.

Dynamism in Retreat

The economy today is suffering from too little change, not too much. I realize this is a provocative claim in the age of the gig economy, automation, and the dawn of artificial intelligence. But the fact is Americans are less likely to start a business, move to another region, or switch jobs now than at any other time on record. Indeed, the U.S. economy is quickly becoming less dynamic in nearly every measurable respect.

Why does this matter? If we believe the problem is too much change, it follows that policy priorities will be oriented around mitigating disruptions and hedging against risk. On the other hand, if we understand the economy has grown too static and too risk averse in too many areas, the logical response is a dynamism-boosting policy agenda — precisely what I believe is urgently needed.

Dynamism can be understood, in essence, as the rate and scale of economic churn. It fuels an economy’s process of creative destruction, enhancing our ability to adapt and allocate resources in a more efficient manner. Historically, the high-churn nature of the U.S. economy acted as a kind of shock absorber in times of economic change or trauma.

Let’s start by assessing the state of dynamism today through three important and interrelated measures: the startup rate, job turnover rate, and domestic migration rate.

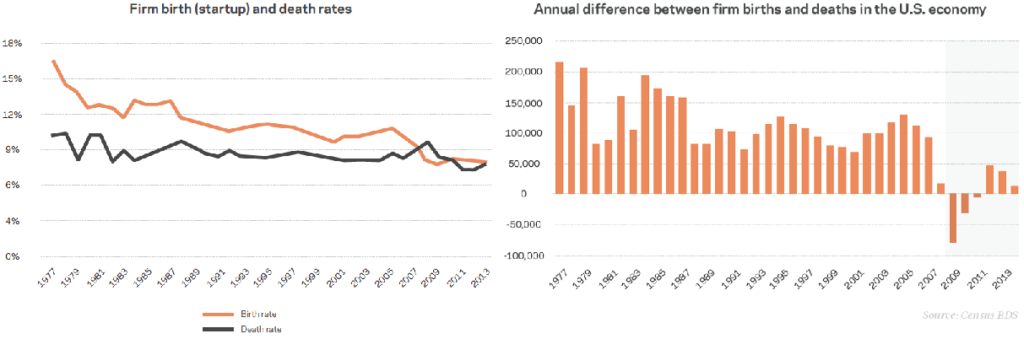

- New firms are becoming scarce. At the core of the broad decline in economic dynamism is a steep drop in new firm formation. The startup rate collapsed during the Great Recession to its lowest point on record — dipping below the closure rate for the first time. Even as the broader economy has improved, the startup rate has barely budged and remains mired at 8.0 percent — narrowly outpacing the firm closure rate (this is important, as we will see below). Even in absolute terms, the economy produced 25 percent fewer new firms in 2014 than it did before the crisis. The decline is pervasive across all regions and industry sectors.

This is a deeply troubling development. New firms are the “creative” part of creative destruction. They help keep the economy in a constant state of rebirth by replacing dying industries, fostering competition with incumbent companies, and producing new and higher wage jobs. When they disappear, the cycle of creative destruction falls out of balance.

It is worth noting that the rate at which firms close has remained fairly stable over the past 30 years. In fact, given all the talk about disruption these days, one might be surprised to see the closure rate currently near its lowest point on record. At least as far as businesses go, the dynamism problem is rooted in anemic birth rates, not spiking closures.

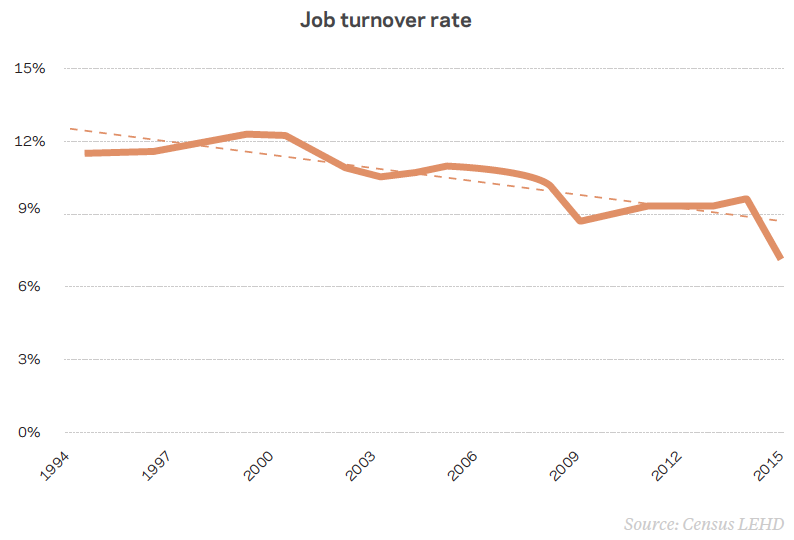

- Job turnover has plummeted. Job turnover is an important sign of labor market flexibility. High turnover was once a key feature of the U.S. economy but has declined substantially from a high of 12.4 percent annually in 1999 to a low of only 7.2 percent in 2015. In other words, only one in every 14 positions turned over in 2015. Disadvantaged workers are the ones most acutely impacted by lower turnover rates. Without churn in the labor market, it’s simply more difficult to find an unoccupied rung on the career ladder. For individuals, low job churn has negative implications for wages. For the broader economy, there is evidence that slower rates of churn meaningfully reduced GDP growth during early stages of the economic recovery.

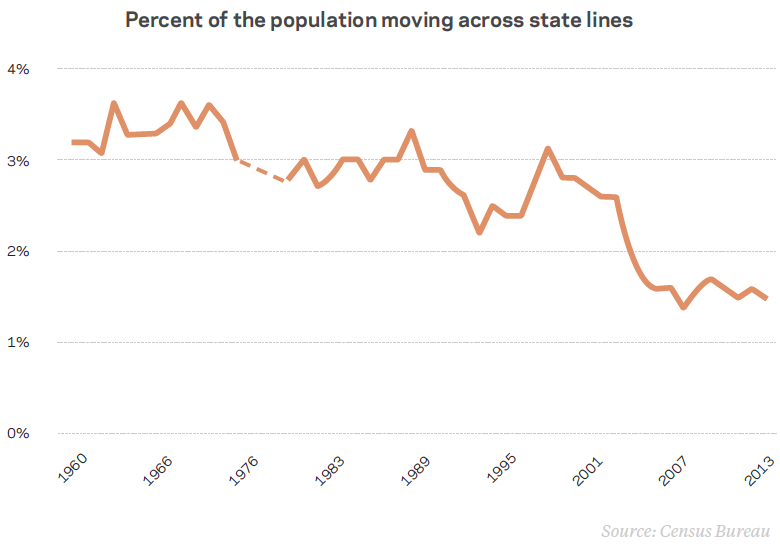

- People are staying put. Americans are far less geographically mobile than they once were. High rates of internal migration historically served as an important adjustment mechanism for the U.S. economy, mitigating downturns as workers moved to areas more rich in opportunity. The domestic migration rate throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was consistently between 3.0 percent and 3.5 percent, and it was above 3.0 percent as recently as the late 1990s. Since then it has fallen by roughly half, settling to a historic low of 1.5 percent. While demographic factors impact domestic migration, the bulk of the trend can be attributed to declining business dynamism. As fewer firms open and close, fewer employment opportunities emerge, and thus, fewer people have reason to move long distances.

Consequences of Declining Dynamism

Let’s now explore some of the consequences of a low-dynamism economy.

Declining Stock of U.S. Firms

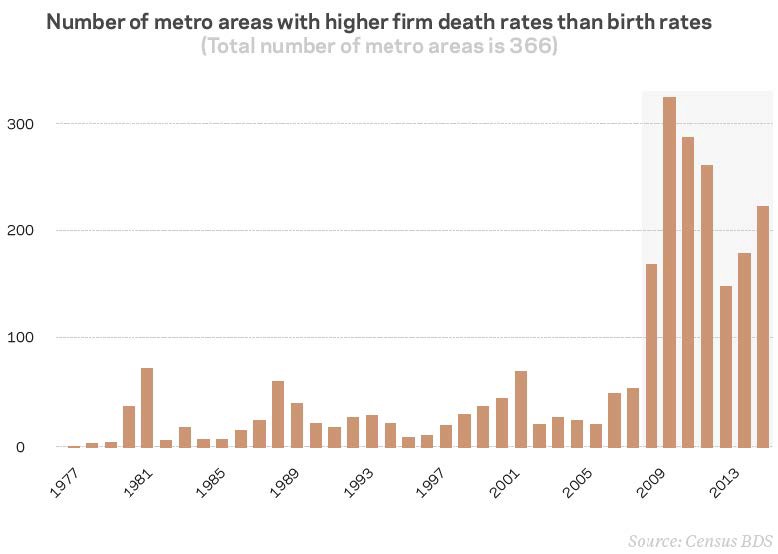

The rapid decline in the U.S. startup rate has ushered in the modern economy’s first period of a shrinking U.S. business sector. Prior to 2008, the vast majority of U.S. metro areas saw more businesses open than close every year. In fact, the share of metro areas generating a net increase in firms in a given year never fell below 80 percent, fueling a steady increase in the total number of firms nationwide — even during years of recession (Figure 4). From 1977 to 2007, the U.S. economy generated an average net increase of roughly 117,000 firms per year (Figure 5).

This trend reversed entirely with the Great Recession. At its worst, nearly 90 percent of metros experienced a net decrease in firms in 2009. Perhaps of even greater concern is that the national recovery has not brought a return to normalcy. As of 2014, more than 60 percent of metro areas continued to lose more firms than they were creating. Even the economy’s best year for net firm formation since the recession (2012) fell far short of its worst year prior to 2008.

To underscore the severe and unprecedented nature of this reversal: Prior to the recession, the United States had never recorded a year-over-year decrease in the number of firms. By 2014, however, the economy’s total stock of firms was 182,000 smaller than it was in 2007 — in spite of an increase of $1.1 trillion in real GDP.

Fewer Jobs

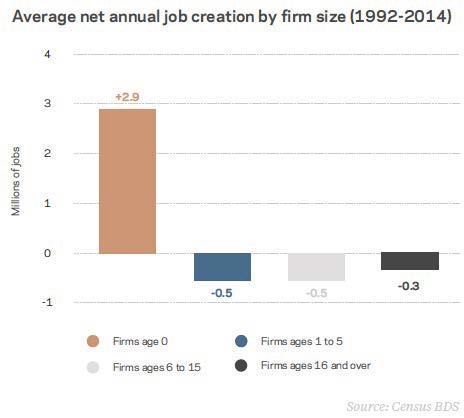

Workers suffer in an economy with fewer firms competing for their labor and less labor market turnover. New firms are the economy’s most potent engine for net job creation and play an underappreciated role in keeping the labor market healthy. In fact, established firms as a cohort tend to shed more jobs than they create in an average year; only new firms are consistently net job creators. Thus, the meager startup rate has served to mute both the quality and quantity of job growth during the current recovery. Our conservative estimate is that the cumulative deficit from a missing generation of new firms between 2007 and 2014 was 3.4 million jobs. At a time when nearly 15 percent of prime working-age men are out of the labor force, diminished startup activity will continue to pose a major impediment to the goal of expanding access to opportunity through quality employment.

Incumbency and Market Concentration

The economy is now dominated by older incumbent firms who are thriving in an environment with fewer new challengers and weaker competitive pressures. Firms that are at least 16 years old are claiming an ever-larger share of the business sector and now employ nearly three-quarters of the country’s workforce, up from 60 percent in the early 1990s. Corporate profits, which normally average around 6 percent of GDP, have averaged over 9 percent of GDP over the recovery. Market concentration is becoming more pervasive. Two-thirds of U.S. industries saw an increase in concentration between 1997 and 2012, with the top firms claiming a larger and larger share of total revenue.

To be clear: Some degree of market concentration is not inherently bad for consumers or the broader economy. However, remarkably high and persistent profits alongside pervasive concentration are a warning sign of economic rents. What should be temporary rewards in a competitive economy now resemble perpetual rewards to incumbency. And the steady creep of regulatory complexity only serves to strengthen incumbents’ hold on the market. Another reason to be concerned by the graying of the business sector is its impact on innovation and productivity. An array of research indicates that firms tend to become more risk averse as they age, while new companies are disproportionately likely to bring radical innovations to market. But with the number of initial public offerings down significantly since the 1990s and number of acquisitions going up, much of the innovation generated by today’s new companies simply goes to directly strengthening — instead of challenging — an incumbent.

Rising Geographic Inequality and Concentrated Growth

The economy has undergone massive changes in recent decades, but few are as obvious as the shifting geographic distribution of new jobs and businesses. The last recession and subsequent years have accelerated a trend towards geographic concentration after decades of decentralizing growth that spread economic activity to more locales. An increasingly narrow set of places are responsible for national rates of growth as an increasingly wide swath of places get left behind. While regional variations have always been a fact of life, the relationship between place and opportunity appears more pronounced than ever.

As the map of economic growth and recovery has changed, so too has the nature of economic opportunity for millions of Americans. Consider these findings:

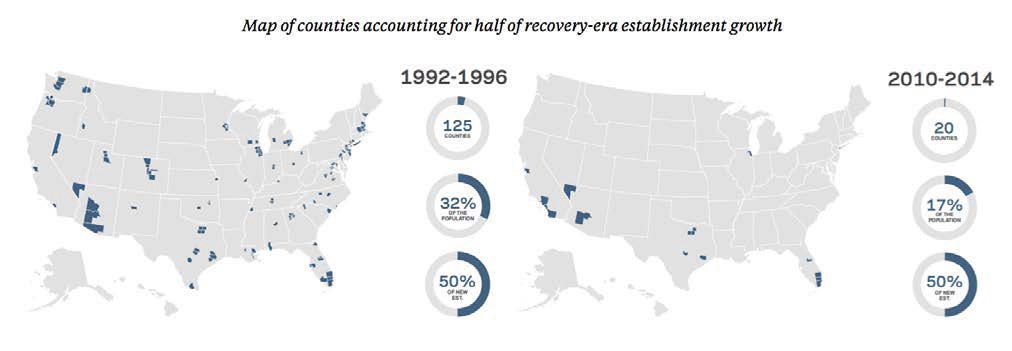

- The local benefits of dynamism are accruing to smaller shares of the population. For example, fully half of the net increase in U.S. firms from 2010 to 2014 was located in only five metro areas: Houston, Dallas, Los Angeles, Miami and New York. These places were home to only 17 percent of the country’s jobs. Compare that to the 1992 to 1996 period, in which 30 metro areas — spread throughout the entire country and housing 40 percent of U.S. employment — produced half the net growth in firms. It is crucial to note: This trend is the result of most places doing worse, not a few places doing better than ever. For example, the New York metro area produced roughly the same increase in firms over the last three economic recovery periods. In other words, the pie itself is getting smaller and the biggest slices are going to resilient large metro areas. The trend with firms and metro areas holds true for counties and business establishments as well. This is important because if fewer new firms were still producing a broad and healthy distribution of growth in business establishments, the detrimental effects would likely be less severe. Instead, we see that half of the net growth in establishments from 2010 to 2014 occurred in just 20 counties home to only 17 percent of the U.S. population. This is again a far cry from the 1992 to 1996 period, during which 125 counties home to roughly a third of the population generated half the net establishment growth.

- Counties losing business establishments have more than tripled over the past three recoveries. The percentage of counties seeing a net decline in business establishments during national recoveries went from 17 percent from 1992 to 1996 to 59 percent from 2010 to 2014. As a result, most U.S. counties had fewer business establishments in 2014 than they did in 2010. Counties seeing a net establishment loss were home to nearly one third of the U.S. population.

- The early recovery passed over the neediest communities. National figures are increasingly unreliable in telling a local story. For example, EIG’s Distressed Communities Index (DCI) project found that U.S. zip codes in the bottom quintile of prosperity saw significant ongoing losses of both jobs and business establishments during the first four years of the national economic recovery. On average, they saw a -6.7 percent change in employment and a -8.3 percent change in establishments. These are places spread throughout every region and housing over 50 million Americans — often adjacent to highly prosperous centers of economic growth. Meanwhile, the top quintile of zip codes saw employment gains of 17.4 percent and establishment growth of 8.8 percent. These findings underscore the consistent disconnect between the national narrative of steady recovery and the deep anxiety many Americans still feel about their own local economies.

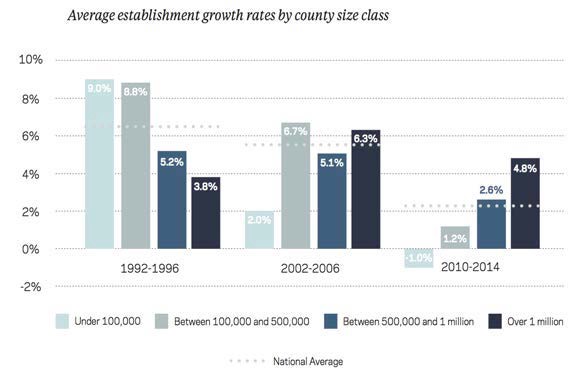

- Small and rural counties experienced a stunning reversal of fortune over the past two decades. Low-density counties went from a 16 percent employment growth rate in the 1992 to 1996 period to a 4.9 percent growth rate from 2010 to 2014. Worse, over the same period, those counties went from leading the nation with a 9.0 percent establishment growth rate to last place with a rate of -1.0 percent. While many flourishing rural and small town communities remain, the landscape of opportunity and economic growth has clearly shifted toward higher density locales.

- The largest counties were the clear winners of the 2010s recovery. As fortunes have faded elsewhere, counties with over one million residents led the nation in employment and establishment growth rates for the first time. This defies the conventional wisdom that growth rates in larger and highly developed cities are by nature slower than growth rates in smaller and less developed ones.

The geographic shift in employment and business growth cannot be explained by population trends alone. For example, roughly one-third of the counties that lost business establishments and one-quarter of the counties that lost jobs during the 2010s recovery actually saw an increase in population. Furthermore, populations increased in more than 20 percent of counties that lost both jobs and establishments.

Upward Mobility

While rumors of the demise of the American Dream have been greatly exaggerated, there are clear signs it is under threat or fenced off in too many American communities. Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and their colleagues at the Equality of Opportunity Project (EOP) have done an enormous service through their research on upward mobility. Thanks to their work, as well as a flurry of other new research into economic mobility and geographic inequality, we understand better than ever just how profoundly geography impacts an individual’s economic destiny.

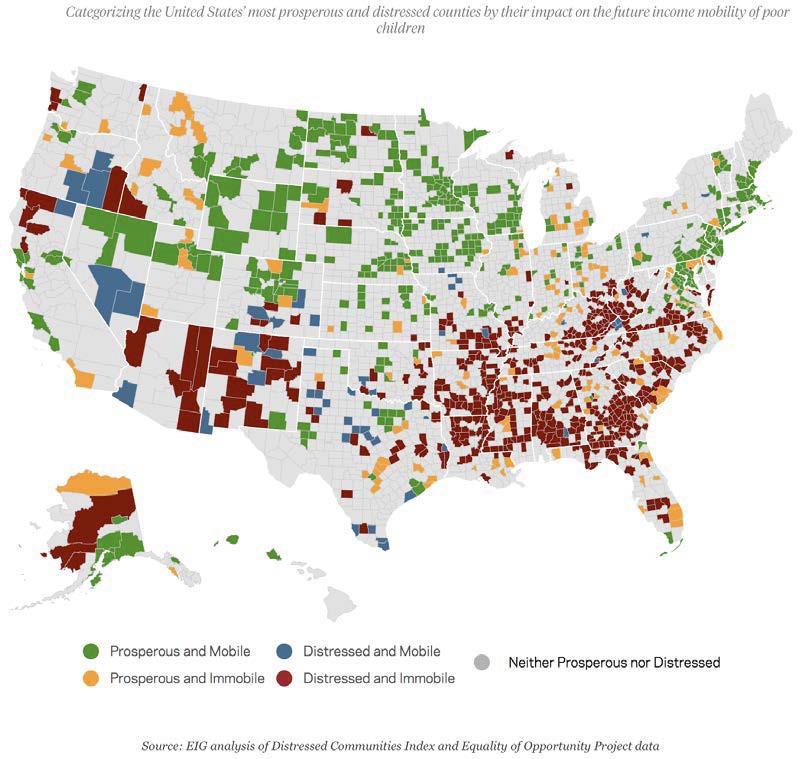

EIG recently merged EOP’s data on economic mobility with its own DCI data on economic wellbeing to examine the relationship between economic well-being and upward mobility in communities across the United States. 12Specifically, we studied counties that fell into the top and bottom fifths of prosperity nationally. We find that county-level economic distress weighs more heavily on children from poor backgrounds than it does on children from wealthier ones, who are better equipped to rise above their surrounding circumstances. Troublingly, 60 percent of Americans under the age of 18 are growing up in counties that historically exert a negative impact on the economic mobility of low-income children.

Our analysis also finds a clear correlation between the degree of prosperity or distress in a county and the extent to which living there boosts or hinders a child’s future earnings potential. Prospering counties are generally more likely to foster upward mobility, although exceptions abound (especially in the Southeast). In fact, more than a quarter of the nation’s most prosperous counties fail to positively impact the future earnings potential of their poor children. Surprisingly, 10 percent of economically distressed counties still manage to promote upward mobility for poor children.

We also found an important silver lining for rural economies: Prosperous rural areas predominantly in the Upper Midwest and Northern Plains are the country’s most powerful engines of upward mobility.

Demographic Considerations

Recent U.S. demographic trends are exacerbating the decline of dynamism. Population growth is a major driver of startup rates both nationally and regionally, so it should come as a concern that the U.S. population grew by only 0.7 percent in 2016 — the slowest since at least the Great Depression. 13 Meanwhile, the median age in the United States has increased by nearly a decade since 1970. Immigration into the United States is an obvious dynamism booster on two fronts. First, it helps keep population growth in positive territory and bends the median age down. Second, immigrants in the United States are highly entrepreneurial; research by the Kauffman Foundation found that immigrants were nearly twice as likely as U.S.-born individuals to start a business in 2014. Not only that, but they are disproportionately likely to start high-growth companies. A study last year found that more than half of the current crop of U.S.-based startups with a valuation of at least $1 billion were started by immigrants.

Guideposts for an Opportunity Agenda

Before discussing potential solutions, let’s play devil’s advocate and ask if declining dynamism is really a problem that can or should be solved. If the decline is inevitable, why bother with useless policy prescriptions? Or, if there are hidden benefits to declining dynamism, why be worried at all?

Dynamism is only worth restoring to the extent that its decline corresponds with downstream negative outcomes. If, for example, we were seeing strong GDP growth, robust labor force participation, increased upward mobility, and strong wage growth, declining dynamism would be a moot point. Unfortunately, we see just the opposite. Furthermore, we can be certain that much of the current dilemma is due to policy choices and thus totally within our control. Nevertheless, our solutions should not fundamentally be aimed at making the economy look more like the past, but rather at ensuring that the benefits of tomorrow’s economy are broadly shared.

Here are five guideposts for a future-oriented opportunity agenda:

1. Focus on new firm creation and competition. Access to opportunity suffers when incumbents are too powerful, markets are too concentrated, and entrepreneurs are an endangered species. Policymakers should rebalance the playing field with lower barriers to entry and greater emphasis on the unique needs of new companies. This includes, among other things, reforming exceedingly complex tax and regulatory regimes, which serve to protect incumbents from competition, and boosting access to capital and talent for new ventures. It also includes accelerating the pipeline of high-skilled workers into the labor market — both through better skills training and by fixing the truly self-defeating U.S. immigration system.

2. Enhance geographic mobility and labor market fluidity. Central to any opportunity agenda should be empowering people to move to places of opportunity and efficiently develop and deploy their skills in the marketplace. Among other things, this means getting rid of onerous occupational licensing requirements, designing a safety net that does not discourage mobility, and revamping local zoning and land use regulations so that high-opportunity areas can accommodate more people.

3. Invest in the future. The United States has benefitted enormously from previous decades of massive public sector investments in infrastructure and basic research, but we often forget why such investments are critical to private sector innovation and dynamism. As we renew our commitment to smart public sector investments, we should also abandon 13 traditional economic development incentives, which too often amount to giveaways that mortgage the future of local communities. New approaches are needed.

4. Growth is still key. The United States is in desperate need of stronger GDP growth, which itself would go a long way to addressing concerns about access to opportunity and upward mobility. A broad pro-growth agenda is necessary, but we should also be bold in incorporating ideas aimed at helping struggling regions regain their footing. Meanwhile, let’s resist the temptation to feel complacent given our relatively strong post-crisis performance in comparison to other developed economies. Their present struggles are a glimpse into our economic future unless we take action soon.

5. We need data. It is hard enough to diagnose complex problems when data are available. Without sound data, we are left with little more than faith-based policymaking. The federal government should protect and expand its investment in the economic statistical agencies and allow for improvements that will make their work even more useful in the years to come. 18 But that is not enough. In light of how little we know about solving long-standing problems (especially related to upward mobility), federal policies should aggressively support novel approaches and reward state and local policy innovation. A more experimental approach to policymaking alongside existing legacy programs could provide a wealth of new data on what works and what should be discarded.

Conclusion

The decline of dynamism poses a threat to economic opportunity and upward mobility for future generations. A country as prosperous as the United States has a moral obligation to devote serious resources and brainpower to ensuring that everyone — especially children from poor backgrounds — has a shot at a better life. This is by no means the job of government alone, but the public sector has a crucial role to play in organizing the necessary attention and resources. The good news is that we retain enormous advantages and resources as a nation — more than enough to meet this challenge if we choose.