The Case for Economic Dynamism

And why it matters for the American worker

Working Americans have far more to lose from an economy that is changing too little and too slowly than from one that is quickly adapting and advancing to new frontiers. But in recent decades, policymakers have ignored signs that the dynamic mechanisms at the heart of our economy were growing weaker. Worse still, policy failures at every level of government have contributed to the sclerosis that has slowly robbed the country of its vitality. From NIMBYs to non-competes, vested interests have steadily weighed the economy down with artificial barriers to mobility, competition, and adaptation. These barriers have made our economy less abundant in opportunity and less able to improve the lives of ordinary Americans.

How can we restore American dynamism and build an economy in which workers can truly thrive?

That question is at the heart of a new paper, “The Case for Economic Dynamism and Why it Matters for the American Worker.”

The decline and potential rebirth of American Dynamism

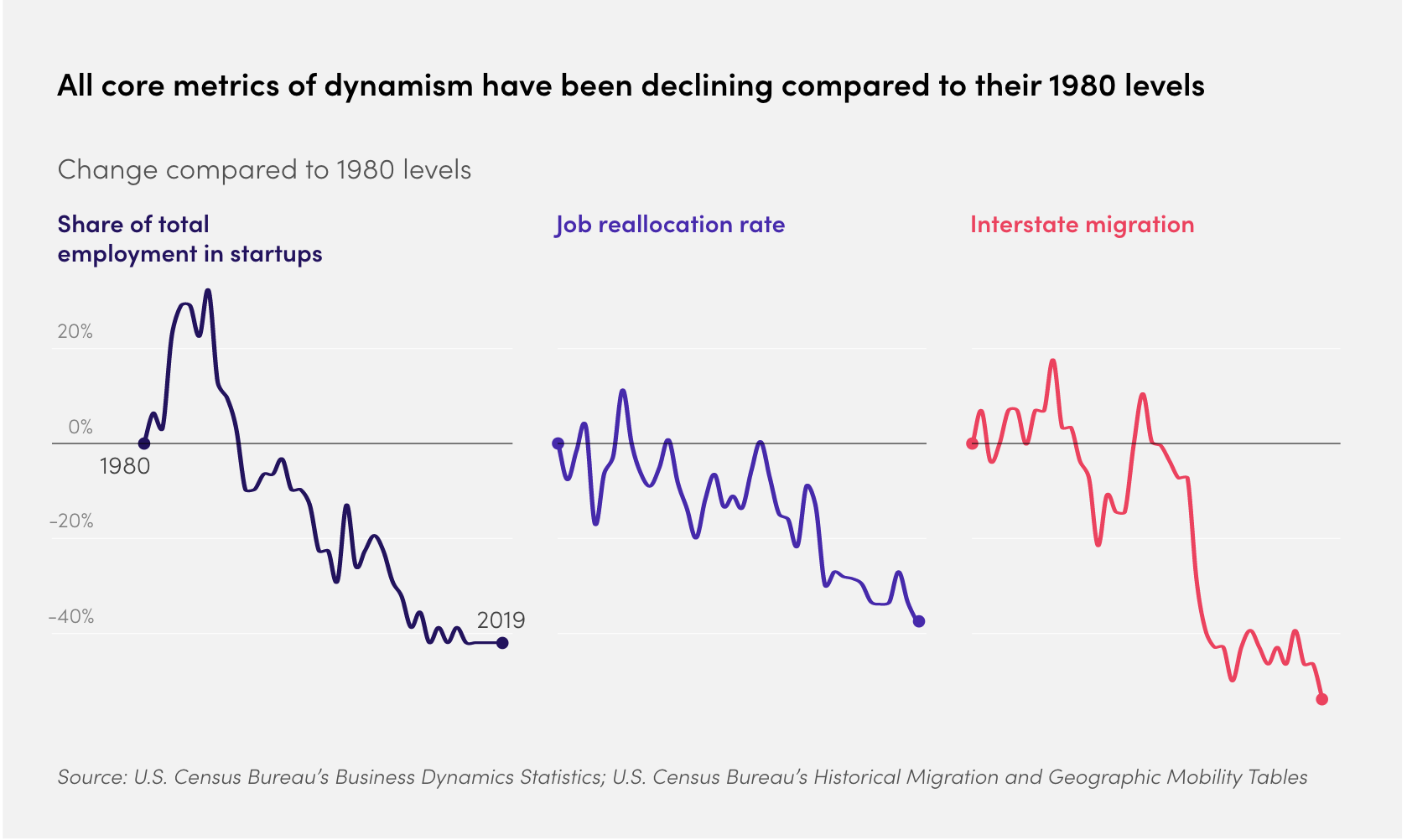

It is a popular myth that the 21st century has been a period of unprecedented economic change and transformation. In reality, American dynamism has been in a decades-long retreat. In the years leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic, startup rates languished near all-time lows. Fewer companies were going public. Corporate America looked old and complacent. Increasingly, too, did American demography. Productivity growth decelerated in spite of promising new technologies. And a country whose people were once known for their restless, pioneering spirit became increasingly stuck in place.

To the surprise of many observers, the pandemic has jolted several key indicators of economic dynamism–at least temporarily–back to life, as Americans are switching jobs and starting businesses at rates not seen in decades. Look beyond the current momentum, however, and it remains clear that powerful headwinds are working against a return to the high-churn qualities that once characterized our economy. These headwinds include our demographic transformation into a rapidly aging society with minimal population growth, a drastic slowdown in the velocity with which knowledge moves through the economy, and the sclerotic buildup of vested interests, domineering incumbents, and veto-wielding stakeholders throughout economic and social life. The weight of these forces makes it harder to build, move, switch jobs, start firms, and compete in the United States, and each calls for a forceful policy response.

What is Dynamism?

The term economic dynamism refers to the rate and pervasiveness of change across industries, geographies, and the labor market in an economy. Key indicators of dynamism traditionally include the rates of business formation and closure, the frequency at which workers quit and switch jobs, and the propensity of workers and families to move to new locations. Economic dynamism is not simply “disruption”; it equates more closely to a state of productive churn and adaptation that enables the economy and its workers to respond to disruption.

Why is dynamism so important to the well-being of American workers?

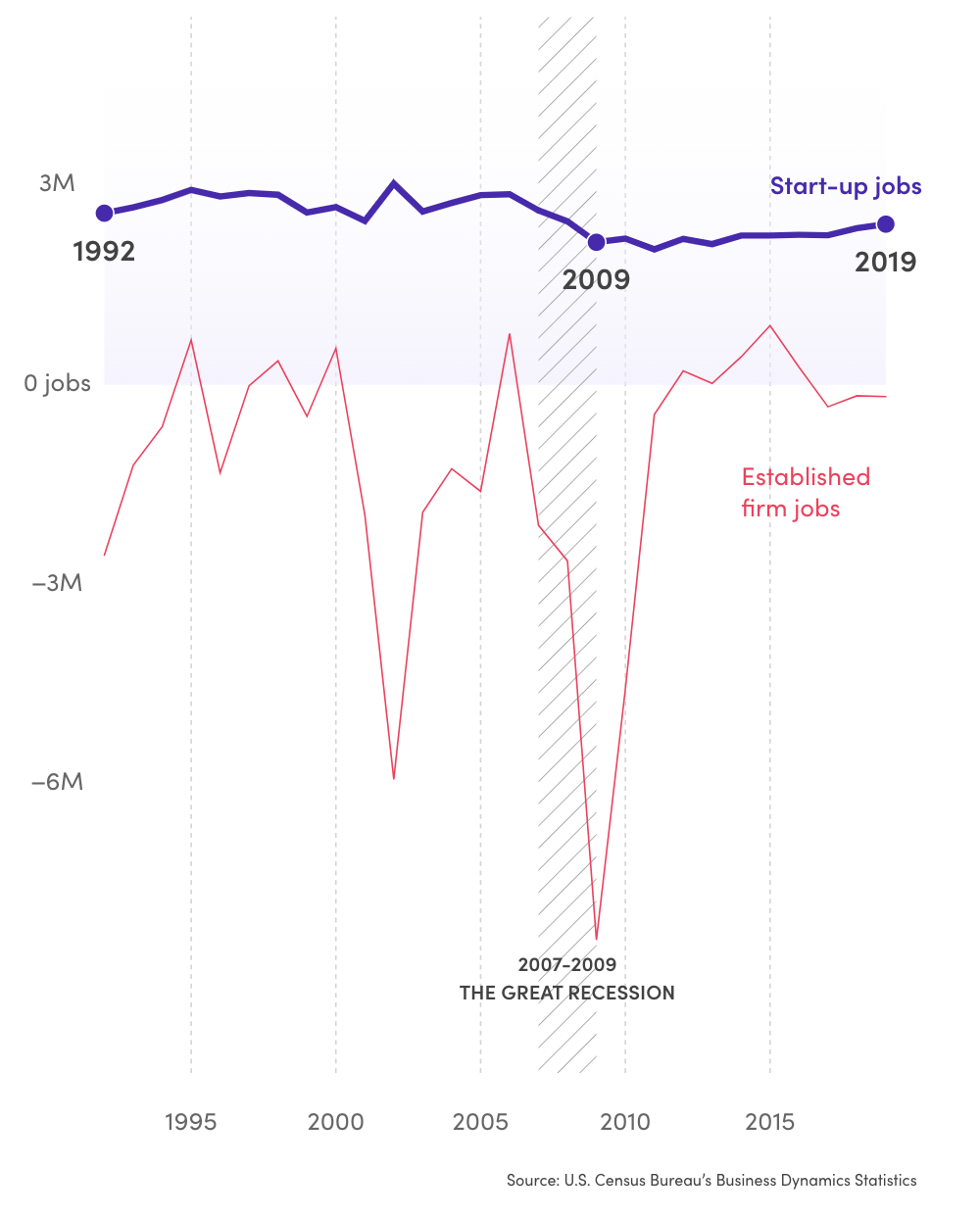

Jobs: New firms generate the bulk of net job growth

The startup rate is one of the most important indicators of economic dynamism. But how do new firms fuel a healthy job market? The answer is simple: they’re the true engine of job creation.

First, consider that established firms grow and decline at predictable rates, with their job gains and losses canceling each other out in most years.

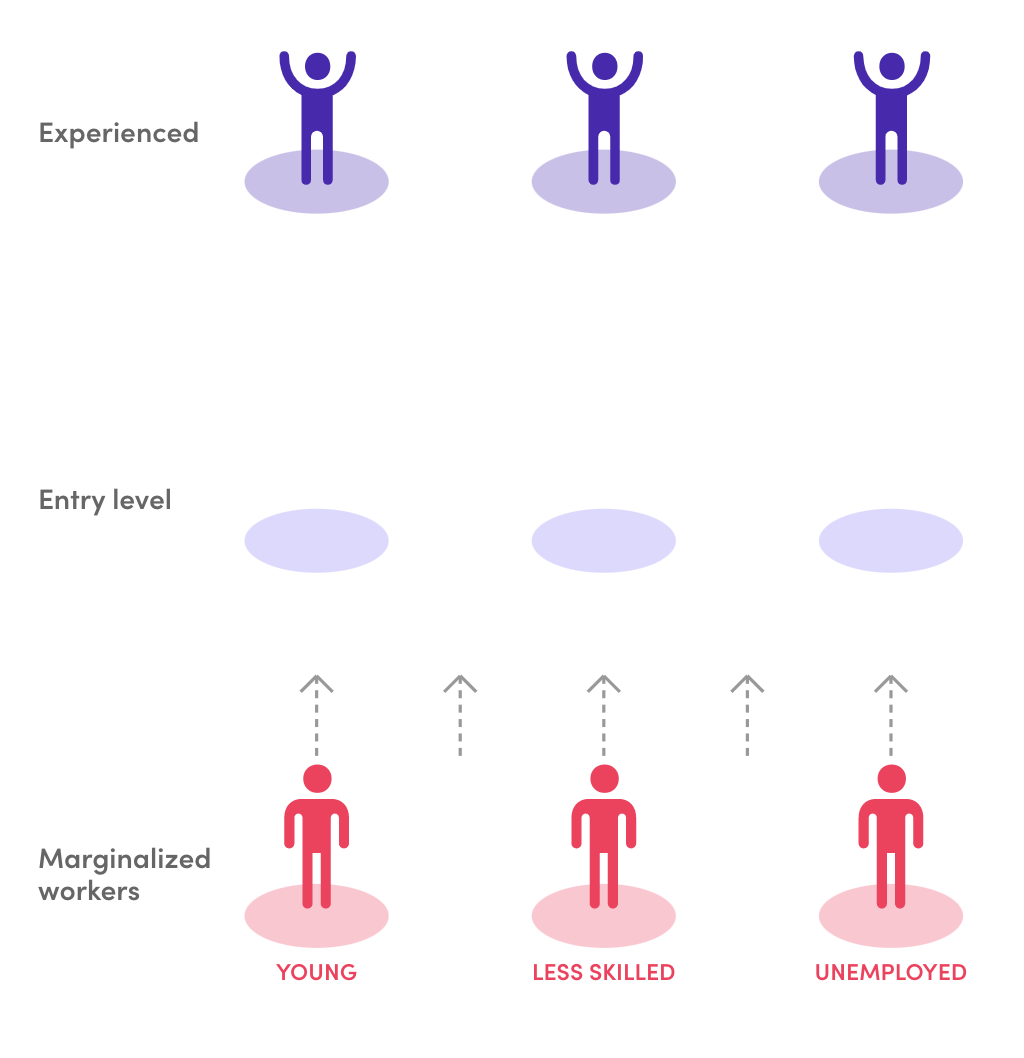

Opportunity: A dynamic economy creates job opportunities for marginalized workers

A dynamic economy doesn’t just create more jobs, it creates more opportunities for marginalized workers to get a step on the career ladder.

For instance, when labor market churn is low, competition for each job opening is more intense and there is less mobility overall. Those in the weakest positions remain on the sidelines.

However, in a more dynamic economy, higher rates of churn free up employment opportunities for those traditionally sidelined workers. It provides its own form of an economic safety net, too, catching displaced workers and pulling them into new occupations and endeavors.

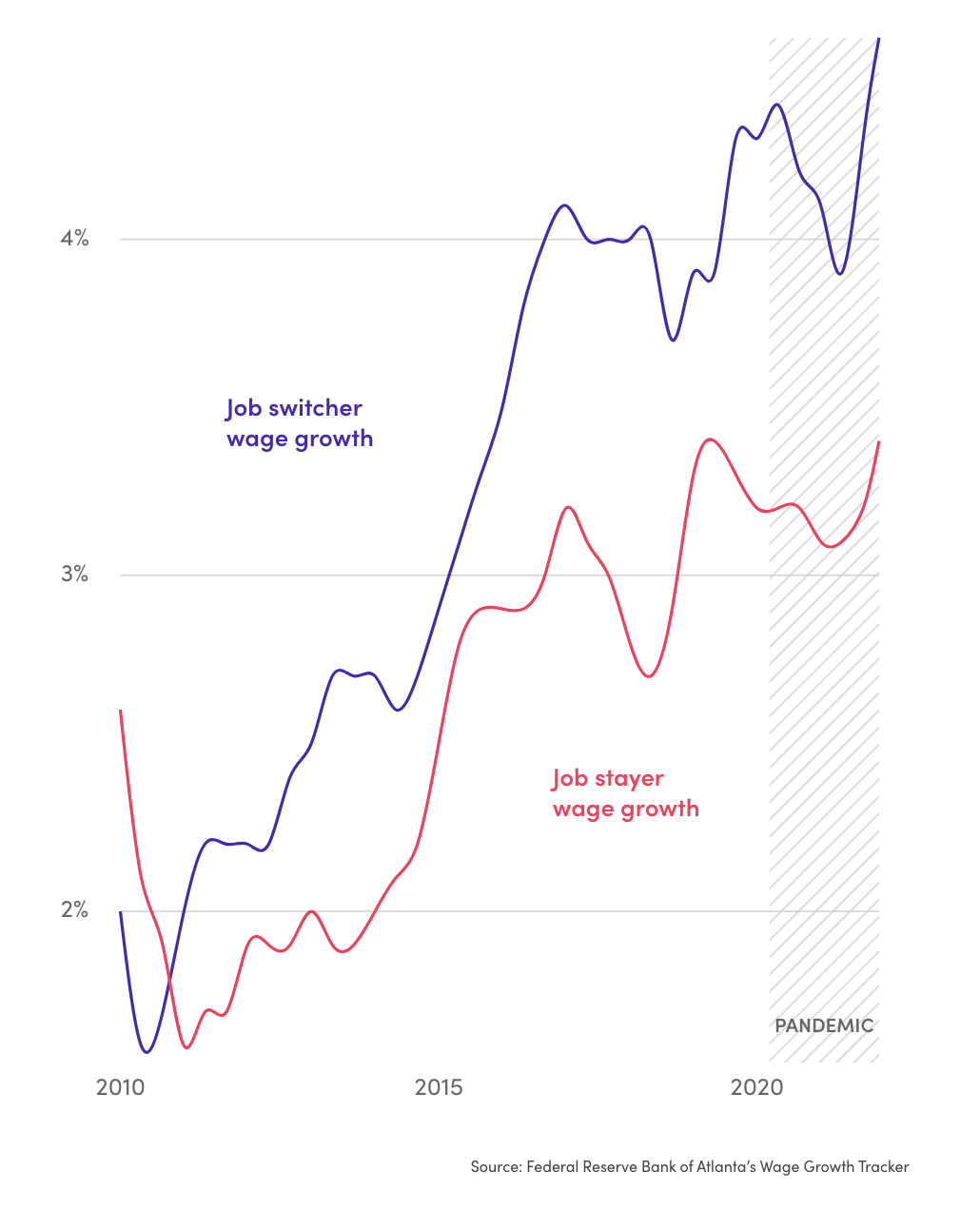

Wages: Dynamic labor markets accelerate wage growth

The competition and job-to-job mobility fostered by dynamism helps power wage gains for workers. In a churning labor market where demand for workers is high and competition is intense, workers gain leverage and have ample opportunities to seek out better jobs and higher wages.

The benefits of a more dynamic labor market have been on clear display during the pandemic, with wage growth for job switchers consistently outpacing that of job stayers by roughly a full percentage point.

The path to renewal

As we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers confront a high-stakes opportunity to restore U.S. economic dynamism and forge a more optimistic, aspirational future for American workers. Such an agenda should be rooted in three fundamental policy goals that would deliver large and widespread benefits for all Americans at virtually no cost to taxpayers.

Americans shouldn’t settle for a future of complacency and managed decline. Policy mistakes compounded over decades have contributed heavily to the country’s diminished vitality, but it is not too late to change course. And change is urgently needed, because a dynamic economy is one that offers the most abundant opportunities for workers to thrive, as well as the best chance to ensure that all Americans share in the benefits of economic growth.