Daniel Newman and Kennedy O’Dell

Over the past several years, the United States has experienced a growing divergence in the economic fates of its so-called superstar cities and the rest of the country. Powerhouses that drove prior eras of the country’s development, with economies typically oriented around the production of goods rather than the provision of services, found themselves left behind. Complementing previous scholars’ work on so-called “legacy cities,” EIG has identified 232 “legacy communities” that have experienced such reversals of fortune. These communities dot the country and include a diverse array of places from Detroit, MI, to Birmingham, AL, to Topeka, KS. Characterized over decades by population decline, a drop in median household incomes, and high housing vacancy rates, these “past-peak” communities face a shared set of headwinds, yet each is also home to a particular host of assets and opportunities.

Legacy communities are home to 1 out of every 7 Americans. Containing 15 percent of the country’s population, these communities are responsible for 14 percent of U.S. GDP. These places are often saddled with vacant buildings and under-performing labor markets, but they are also home to nation-leading universities, headquarters of major corporations, and world-class healthcare facilities—not to mention talent and grit. While struggle is an essential element of the legacy story, so too is resilience.

Legacy communities are a vital part of the American economy and the country’s broader social fabric. Ensuring their economic health and success is thus an essential part of forging a new era of inclusive dynamism in the wake of the COVID crisis. Some legacy communities had already started bouncing back prior to the COVID pandemic, but the combined health crisis and economic downturn has put that recovery in jeopardy. Asking individuals to simply move from these struggling areas is not a solution that does justice to these places or the people who call them home. The Legacy Cities Series, of which this post is a part, seeks to elevate these places in discussions of national urban and economic policy that are too often dominated by the issues facing elite superstar cities. Building a better understanding of legacy communities—where they are, what they look like, who lives in them—is an essential part of forcing that recalibration.

What does it mean to be a legacy community?

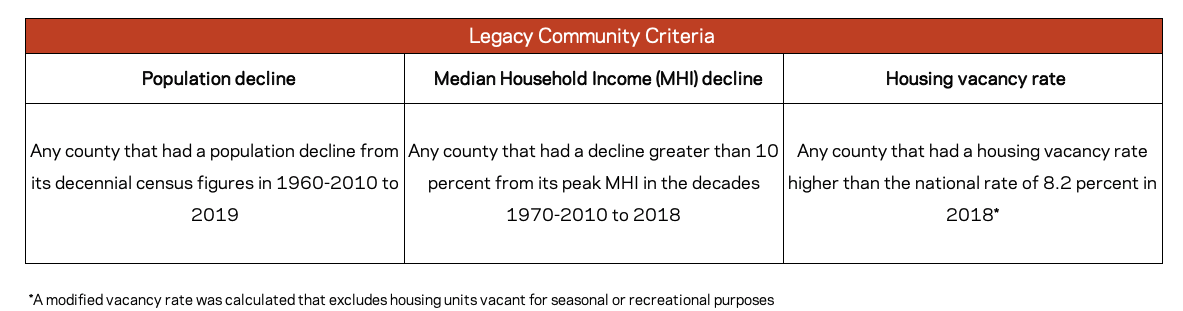

The EIG criteria for identifying legacy communities are deliberately designed to be broad and inclusive to capture the full spectrum of places whose economic heyday lies in the past. EIG determines legacy status at the county level because it provides the most plentiful and consistent data through time, as city boundaries may change from decade to decade. “Community” and “county” are used interchangeably throughout this analysis. The selection excludes counties with a current population less than 50,000 as a way to remove predominantly rural parts of the country. This size requirement does not mean that lower population places are not important to consider, only that they are dealing with rural dynamics that make them distinct from the designation at hand.

EIG chose three elements that define the legacy community experience: population loss, real median household income declines, and elevated housing vacancy rates (see table above for specific indicators). Because communities experience decline in different ways, EIG chose a flexible definition that would allow communities to receive the legacy designation if they met at least two of the three qualifying criteria. In total, 232 counties met the minimum population requirement and at least two of the criteria.

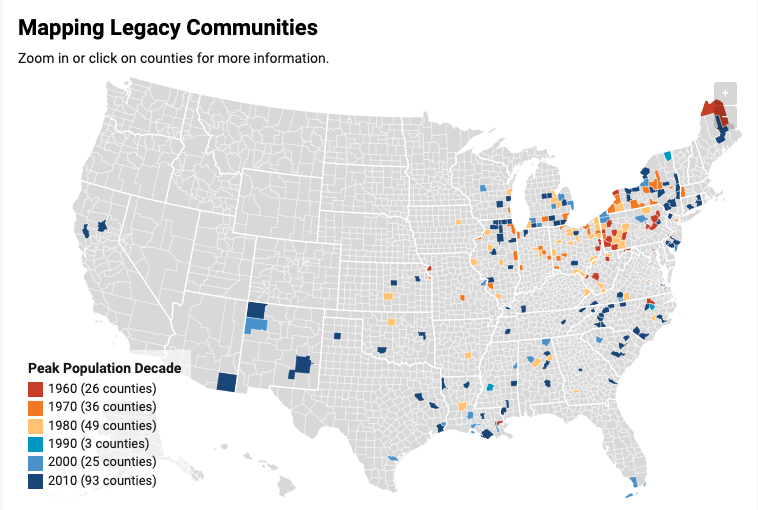

Where are legacy communities?

The 232 qualifying legacy counties represent every region of the country and stretch across 32 states. Home to approximately 48 million people, these communities have been—and still are—valuable contributors to the country’s history, culture, and economy. In 2018 they produced $2.9 trillion worth of goods and services, or 14 percent of the nation’s GDP.

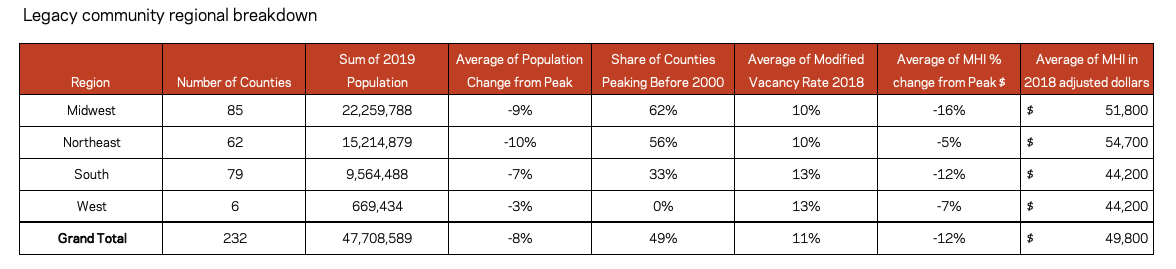

While the Midwest is home to the largest regional concentration of legacy counties (85), the state with the most is actually in the Northeast: New York’s 26 legacy communities largely blanket the formerly industrial Upstate region. Three additional states are home to at least 20 legacy counties: Ohio (25), Pennsylvania (23), and Illinois (20).

The typical image of a formerly industrial Rust Belt city that many identify as a legacy community fails to fully capture the universe of places that have similarly fallen from a more prosperous past. The sprawling South, for instance, actually holds the second most legacy counties (79), many of which are located in diverse parts of Virginia, North Carolina, and Louisiana.

Southern legacy communities stand out from the rest in several ways. Only one-third peaked in population before the year 2000, compared to 56 percent in the Northeast and 62 percent in the Midwest. Black residents make up over one-quarter of the population on average, nearly three times the share in the typical Midwestern county. Generally, legacy communities in the South tend to be lower population places—despite having nearly as many legacy counties as the Midwest, the region is home to just over 9.5 million people in legacy communities compared to the 22.3 million who reside in Midwestern ones.

Despite the population gap, the South and Midwest share an important commonality: legacy communities in both regions have experienced much larger declines in their median household incomes on average than their peers in the Northeast and West. While median household incomes in Northeastern legacy communities have declined by 5 percent on average from their peaks, legacy counties in the harder-hit Midwest and South average declines of 16 percent and 12 percent respectively.

How do legacy communities compare to their peers?

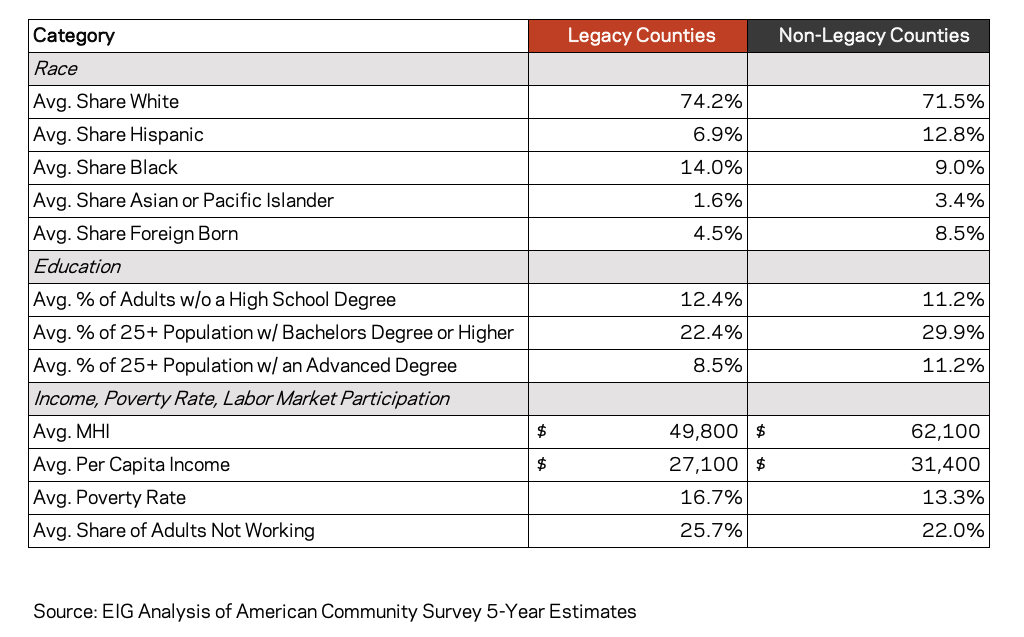

Comparing legacy counties to their non-legacy peers with at least 50,000 residents on key demographic and economic indicators such as education, poverty, and labor market participation paints a clearer picture of the divergent experiences facing residents in legacy communities and their non-legacy counterparts.

Demographics

Racial characteristics of legacy communities vary greatly across the country, and differences can be obscured when analyzed together as a group. Within the same county, stark contrasts often exist in the racial makeup between the central cities and the surrounding communities. EIG’s Neighborhood Poverty Project offers a lens for observing this type of intracounty variation. Regional differences can also be obscured by national averages. Yet on average, both legacy and non-legacy counties tend to be overwhelmingly white. At the same time, the legacy share of Black residents is five points higher than non-legacy places, likely reflecting the prevalence of large urban clusters in the Midwest and the significant number of counties included in the South. Hispanic Americans, for their part, are relatively underrepresented in legacy communities: the average share of Hispanic residents is only around half what it is in the typical non-legacy county.

Legacy communities also appear to be lagging behind their peers in terms of the number of immigrants. Immigrants bring population growth, entrepreneurial energy, and often a more youthful workforce. Yet just over 4 percent of legacy county residents were born outside of the United States. That is about half the share of non-legacy places, signaling that many legacy communities appear to be missing out on these vital flows.

Education

One of the starkest differences shows up in the share of residents holding a college degree. In the typical legacy community, 22 percent of residents held at least a four-year degree. Across comparable counties nationally, that figure stood at 30 percent. In a job market that increasingly restricts many well-paying jobs to those who possess a college degree, these figures suggest that an especially large share of legacy community residents may struggle to obtain good jobs.

Employment

Many legacy community labor markets were already struggling prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the crisis has likely deepened distress. Prior to the pandemic, legacy communities reported a higher share of prime age adults (25-54 years old) not working than their non-legacy peers. On average, 26 percent of adults in these places reported not working in 2018 compared to 22 percent in non-legacy communities. Recent research brings to light the devastating long-term effects that localized recessions (which most legacy cities by definition have experienced) can have, including the fact that places typically fail to recoup all of their initial employment losses, leading to permanently higher rates of adults being out of work.

Income

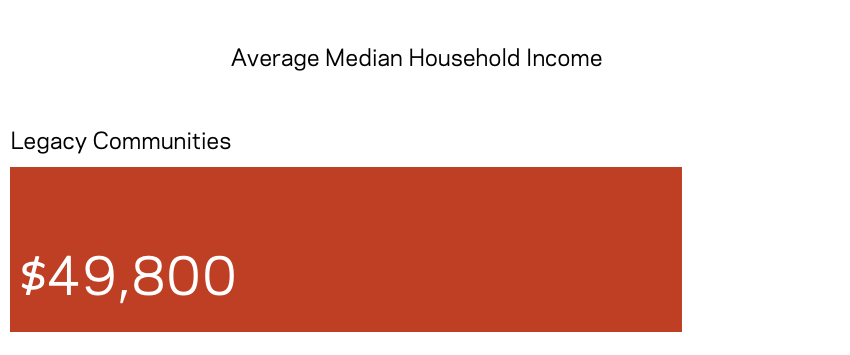

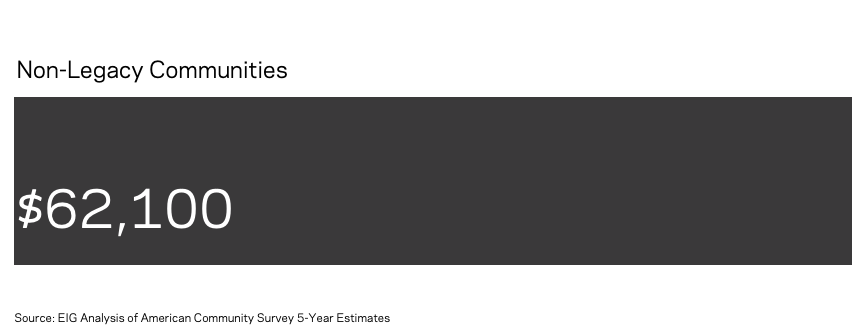

Legacy community households typically take in less money than their peers. While the average median household income (MHI) for non-legacy communities was $62,100 in 2018, the average in legacy counties was only $49,800, over $12,000 less. Using another measure of earnings, per capita personal income, shows that legacy county income was $27,100 per person in 2018, equal to just 86 percent of the average non-legacy community per capita income.

Poverty rates also tend to be elevated, as the average share of legacy county residents living below the poverty line stood at 17 percent, four percentage points higher than in non-legacy counties.

Industry Mix

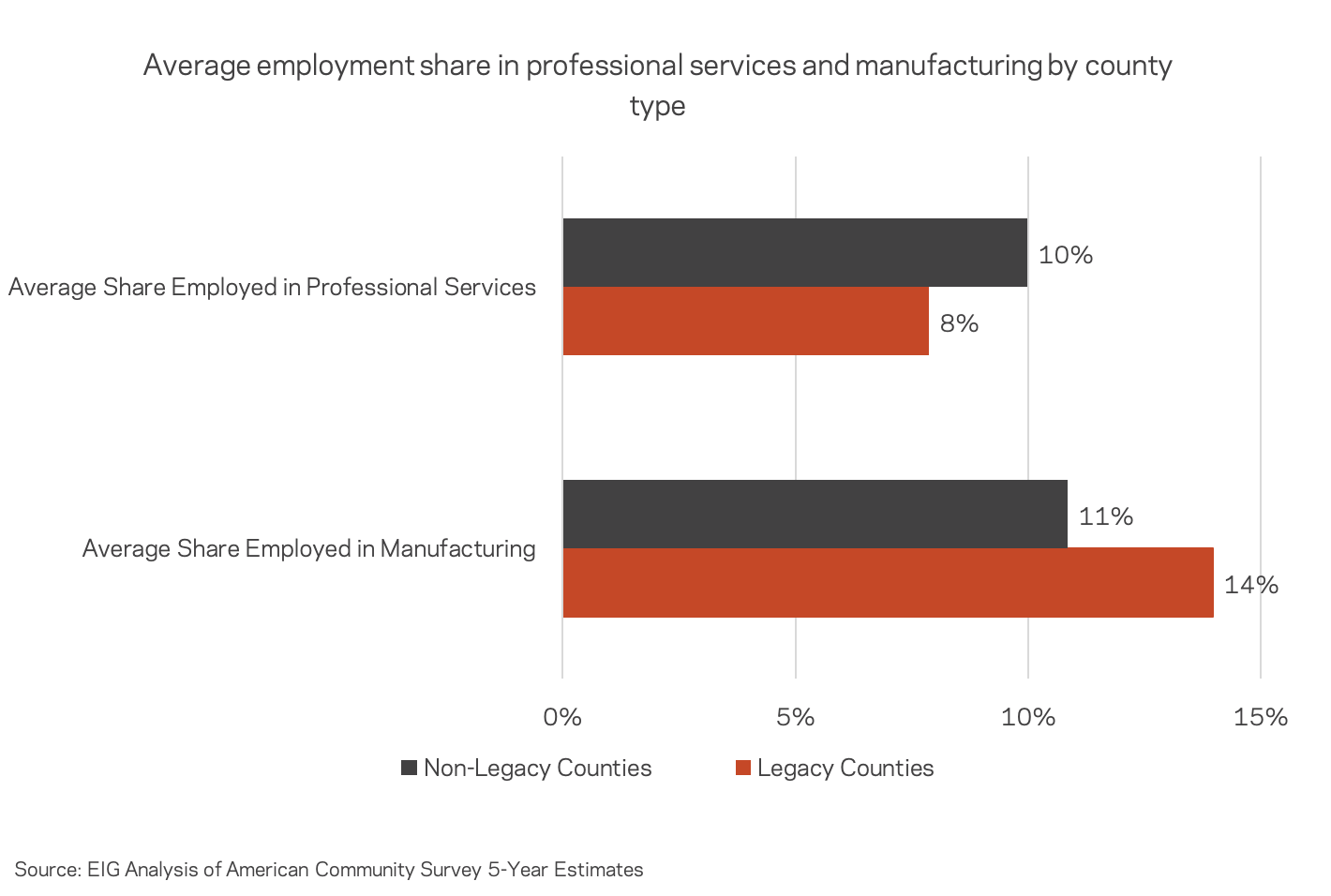

The typical industry make-up varies between the two types of communities. True to reputation, legacy communities remain more oriented towards manufacturing. The varying labor market structures in each type of community are at least in part driving the gap in median household income as the clustering of high-paying professional services jobs in non-legacy cities widens the wage gap between the average legacy city worker and their non-legacy counterpart.

Housing

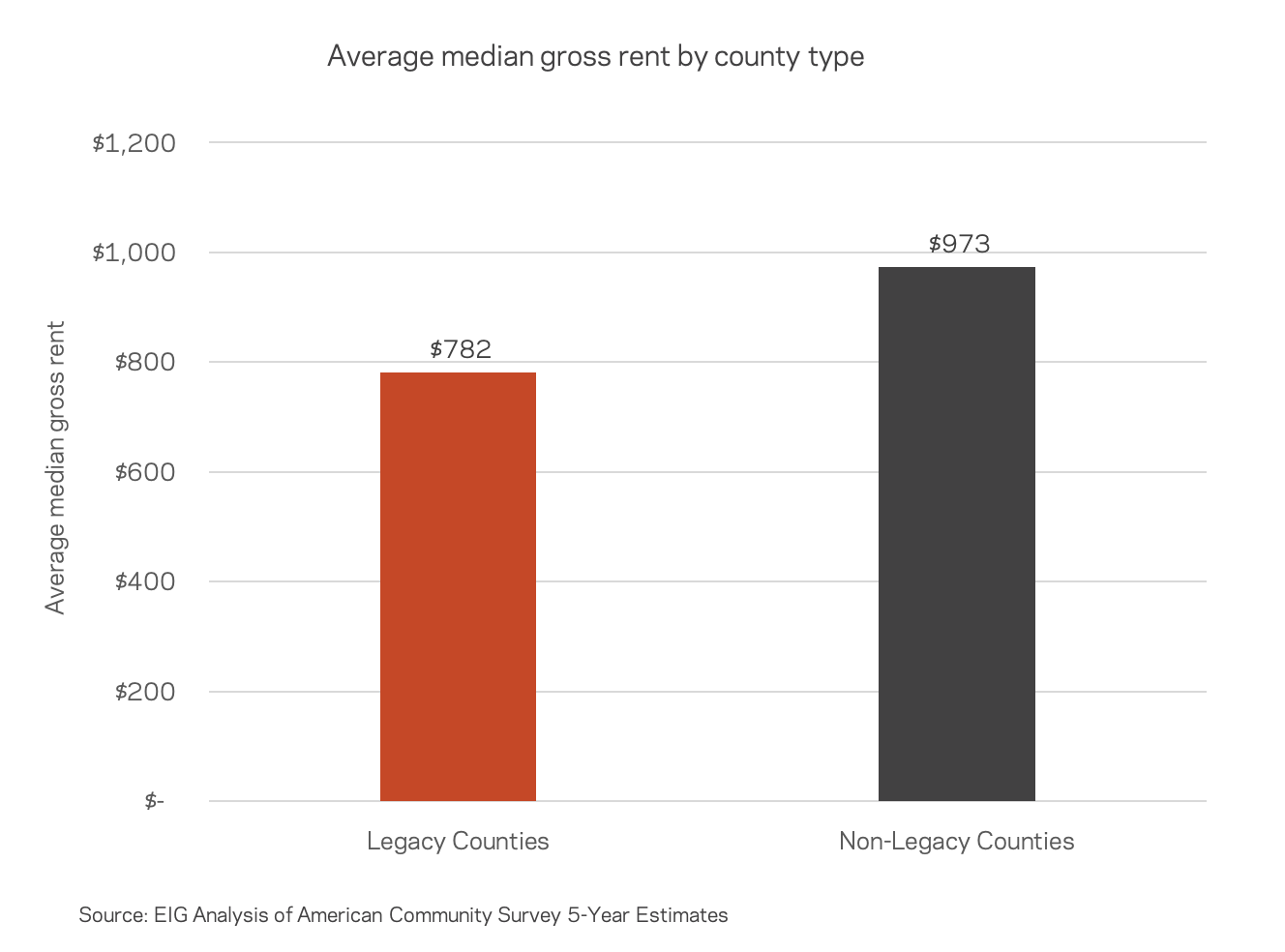

An oft-touted characteristic of legacy communities is their affordability compared to coastal cities. Affordability, however, is relative. Median gross rent is almost $200 less per month in legacy communities than non-legacy communities—$782 and $973 dollars, respectively. Yet about half of households are rent-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of monthly income on rent, in both legacy and non-legacy communities. This means that what looks affordable from the outside and may be affordable in practice for incoming workers remains a challenge for existing residents in historically distressed labor markets.

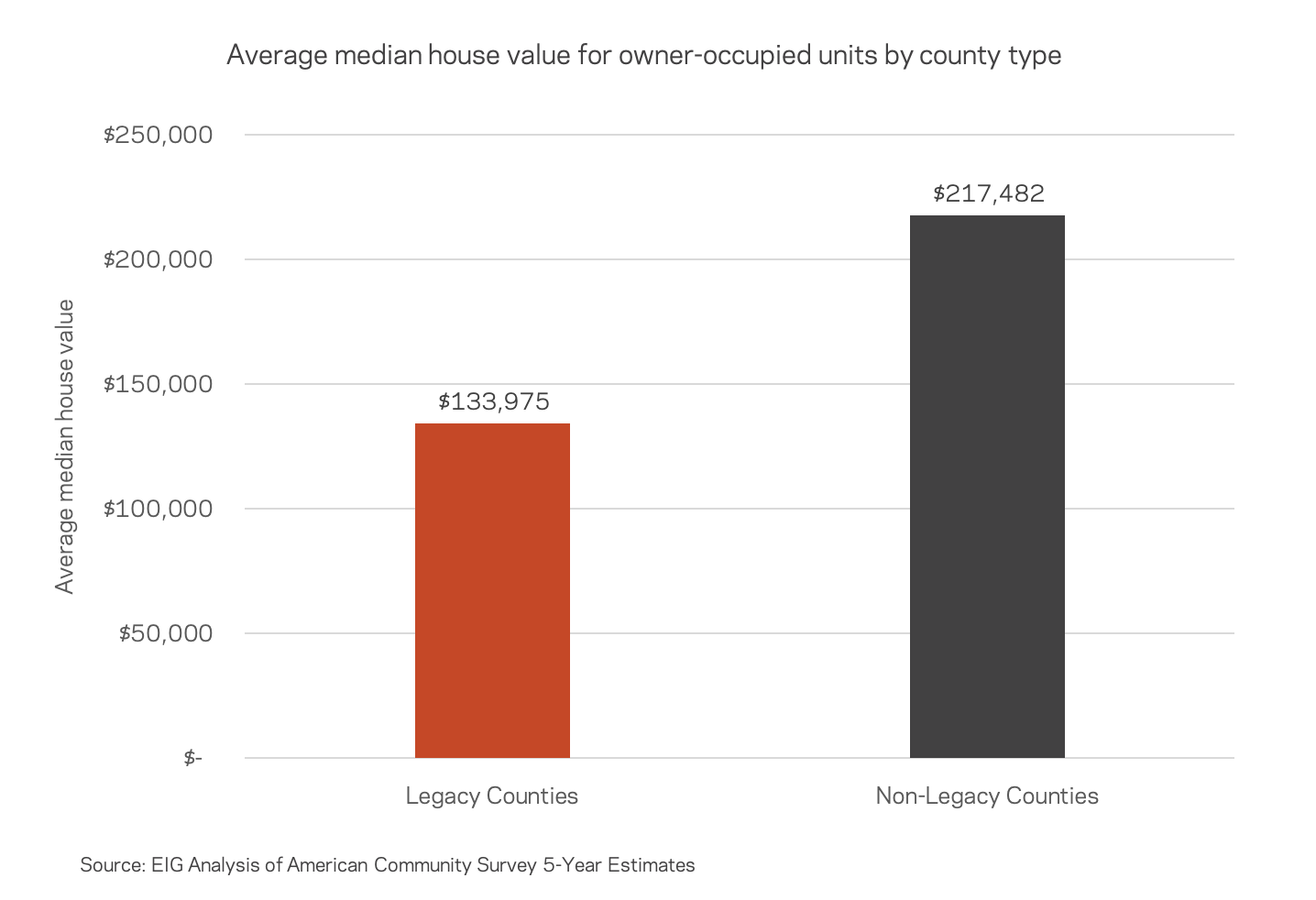

Stark gaps exist in terms of housing values as well. The average median house value in legacy communities is $134,000, $12,800 below the $146,800 average for all counties. However, with non-legacy counties reporting an average median house value of $217,500, the gap between legacy communities and their peers is enormous. This large gap reflects different experiences of population concentration—while legacy communities past peak deal with an excess of developed property, neglect, and falling home values, non-legacy communities continue to see housing values climb thanks to in-migration and amenity concentration.

Where do legacy communities go from here?

Legacy communities are a vital part of the American economy. Yet, the economic recovery from the Great Recession largely left them behind, leaving their economies and populations especially vulnerable in the face of today’s intertwined economic and public health crises. If each legacy community’s GDP, population, and median household income had grown by just one additional percentage point—in total, not even annualized—between 2010 and 2018, there would have been nearly $24 billion in additional economic output, 44 fewer cities with net population loss, and an extra $505 in the average median household income across legacy communities.

A renewed agenda to revitalize our legacy communities is in the interest of all Americans, no matter where they live. Restoring economic opportunity in these places would do much to begin healing the nation’s social and political divides, for starters. Legacy communities were once places of economic success and growth for many, and they still sustain millions. They can thrive again, especially if policymakers at all levels bring a renewed focus to these places and begin to assess them through the lenses of assets and possibilities. Several legacy communities are already on their way to bouncing back and prove that renewal is achievable. Fifteen legacy communities, including the counties housing St. Louis and Baltimore, recorded real median household incomes in 2018 that were above their peaks from decades ago.

These places and the tens of millions of Americans who live in them matter. The EIG Legacy Cities series aims to lift voices from legacy communities in order to build a clearer and deeper understanding of both their immense potential and their distinct and pressing needs. The past decade of urban thought in the United States was largely dominated by the issues and preoccupations of superstar cities and elite metropolitan areas. Theories and models forged in those ecosystems were poorly adapted to the very different market circumstances facing most legacy communities. As the toolkit for the next decade comes together against the backdrop of the country’s greatest economic challenge since the Great Depression, we hope this platform can become a forum for debate and ideas around the economic restoration of some of the country’s greatest assets—its legacy communities.