By Jason Segedy

My name is Jason Segedy, and I am EIG’s Legacy Cities Fellow. The Fellowship offers a platform for emerging leaders from the heartland to shape the national conversation on how to forge a more dynamic and prosperous future. As Fellow, I will serve as a correspondent for the Legacy Cities Series, exploring the people who live in these legacy cities while examining a range of social and economic issues including housing, jobs, neighborhoods, urban redevelopment, the real estate market, and governance.

Our overall goal is to offer a glimpse into the often overlooked communities in our nation’s heartland. We will describe the challenges and opportunities before them through the lens of someone with personal and professional ties to an older, industrial city.

I was born in Akron, Ohio during the early 1970s – the beginning of profound economic decline for the city. Most of my life revolved around Akron. The church where I was baptized and the home I grew up in are both a short walk away from my current home. I simply love everything about this city, including our past.

In 1925, Akron produced half of the tires on the planet. It was once home to the corporate headquarters of four of the five largest rubber and tire manufacturers in the U.S. – Goodyear Tire & Rubber, Firestone Tire & Rubber, B.F. Goodrich, and General Tire. Nearly 60,000 people worked in the production facilities of these companies, as well as many other smaller rubber and tire manufacturers.

After reaching a peak population of 290,000 in 1960, however, manufacturers began to relocate production to more modern, non-union factories in the South. By the 1970s, Akron lost nearly 14 percent of its population as a result of the collapse of the rubber industry. By the end of the 1980s, Goodyear was the only corporate headquarters that remained. Other companies were bought-out by foreign competitors, and their North American headquarters were relocated to the South.

Today, Akron’s population has stabilized at 198,000, and its economy has become a center for higher education and health care. Although the smokestacks are gone, Akron remains a global center for the rubber and tire industry with thousands of jobs in polymer engineering, advanced materials, and research and development.

Akron is representative of the legacy cities experience, but it’s not alone. Many cities like Buffalo, Cleveland, Dayton, Detroit, Erie, Flint, Rochester, South Bend, Toledo, and Youngstown have experienced incredible ups and downs over the last 150 years.

These cities were some of the largest and fastest-growing cities in the nation by World War I. But after World War II, these cities began a painful period of economic and social decline, as three national trends – the decline and outsourcing of manufacturing, regional outmigration to the Sunbelt, and rapid suburbanization – converged on these communities.

Although many started to stabilize in the 2000s, the Great Recession decimated their local housing markets. A winner-take-all global economy led to growing economic divergence and disparities between these legacy cities and Sunbelt and coastal cities and even resulted in a Hunger Games-like dynamic between these cities and their own suburbs.

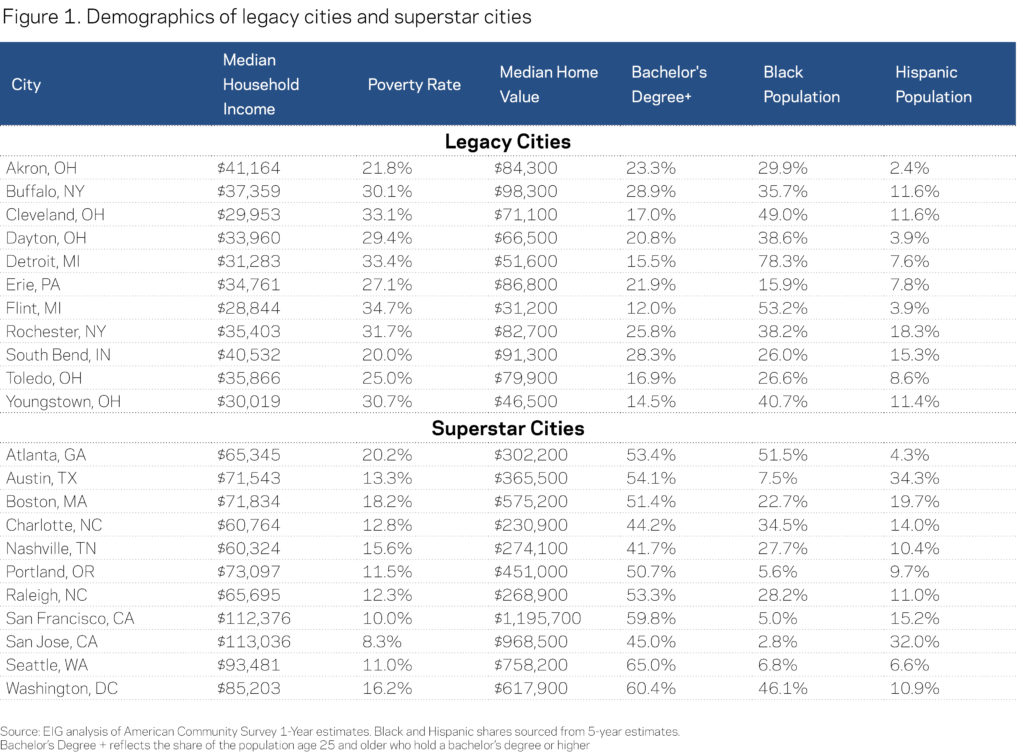

Figure 1 illustrates this divergence in terms of median household incomes, poverty rate, home values, educational attainment, and racial composition. Not only have many legacy cities fallen behind their superstar city counterparts, but they are often islands of poverty and disinvestment in racially-segregated metro regions that are otherwise relatively stable – as EIG’s Distressed Communities Index shows.

Today, it is a virtual certainty that COVID-19 will result in the largest and most profound disruption to our economy and our way of life than any event since the Great Depression and World War II.

The negative impact on legacy cities will likely be profound and potentially devastating – affecting municipal revenues (58 percent of Akron’s general fund budget relies on the income tax), small businesses, and the everyday people who already struggle to make ends meet.

However, it is possible that disruptions to the world economy and global supply chains might upend the status-quo of the past. This result could prove beneficial to cities in the nation’s heartland that are ideal locations for transportation, distribution, and logistics. Most importantly, these legacy cities still have the production of tangible goods embedded deep into their economic DNA.

Although their futures are uncertain, let’s be clear – these cities are not going anywhere. The U-Haul School of Urban Policy where residents simply move on to greener pastures is impractical and foolish. The hard-working people who call these legacy cities home are proud and deserve better than a “just move” economic policy.

So, the questions that we will explore throughout the Legacy Cities Series will focus on how to revitalize these cities. What can be done? How should it be done? Who should be doing it?

I am not ashamed of the Rust Belt. Though our past is difficult to navigate, we can’t be held captive by it. But we also can’t ignore it and pretend that it didn’t shape where we live. It is in our nature as humans to evolve and crave stability. That paradox is who we are. So, paving a way forward requires us to stand on the shoulders of past giants.

The future will belong to the cities that are able to be unashamed, yet desire to transcend. And I look forward to taking this journey with you.

Jason Segedy is the Economic Innovation Group’s inaugural Legacy Cities Fellow. You can learn more about EIG’s Legacy Cities Fellowship and Jason’s background here.