On October 24, 2025, the Economic Innovation Group submitted a comment letter to the Department of Homeland Security in response to its proposed rule, Weighted Selection Process for Registrants and Petitioners Seeking To File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions. The letter provides detailed recommendations and proposes alternative policies designed to more effectively prioritize and select the most highly skilled workers for the H-1B program.

Chief, Business and Foreign Workers Division

Office of Policy and Strategy

Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

5900 Capital Gateway Drive, Camp Springs, MD 20746

Phone: 240-721-3000

RE: DHS Docket No. USCIS-2025-0040, Weighted Selection Process for Registrants and Petitioners Seeking To File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions

Dear Sir or Madam:

The Economic Innovation Group (EIG) is a bipartisan economic research and advocacy organization dedicated to fostering a more dynamic and entrepreneurial American economy. We commend the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for its intention to overhaul the H-1B lottery in a manner that “would favor the allocation of H-1B visas to higher skilled and higher paid aliens.” Unfortunately, the agency’s current proposal would fail to accomplish its stated goals and in fact would place them further out of reach.

Instead of prioritizing new H-1B applicants according to pay, the proposed rule gives greater weight to those applicants whose jobs are tagged with higher “Wage Levels,” as defined by the Department of Labor. These Wage Levels are only weakly correlated with actual salary or proffered wages. The rule attempts to prioritize applicants whose wages are high relative to other workers in their same occupation and labor market — but it does not prioritize between occupations or labor markets. The result is that the rule would prioritize many lower-skilled, lower-paid workers over other applicants with much higher salaries. This is a mistake that deeply undermines the purpose of the rule, which is to prioritize top talent with skills that are both scarce and in high demand.

Beyond the proposed rule’s failure to prioritize the highest-earning applicants, the proposal suffers from three additional problems:

- The rule creates a new incentive to commit fraud by rewarding employers who miscode sponsored workers into lower-paying occupations.

- The rule would not reduce the abuse of the H-1B program by IT outsourcers and staffing companies, a stated motivation of the rule. According to our estimates and others, the proposal would actually increase this misuse of the program.

- The rule does not alleviate the fundamental problem with the current H-1B lottery: uncertainty. An employer offering an exceptionally talented professional a $300,000 salary, for example, would have no certainty of winning the weighted lottery. That is not an acceptable outcome for America’s flagship skilled immigration program.

In this comment letter, we elaborate on the flaws of the proposed rule and offer a better, occupation-agnostic system for DHS to prioritize simultaneously submitted applications. Our proposed alternative would lead to the expected median annual wage of H-1Bs being $31,000 (29 percent) higher than the current rule and $40,000 (41 percent) higher than the status quo random lottery. While the proposed rule would lead to more IT outsourcers winning H-1B visas than the status quo lottery, our proposal reduces these notorious companies’ use of the H-1B by 80 percent.

Compared to the proposed rule, our proposed alternative improves the selection and retention of exceptional early-career workers and yields larger net fiscal benefits to the United States than either the proposed rule or current policy.

Section 1: The Proposed Rule Misidentifies Talent and Will Systematically Disadvantage Top Earners.

DHS is correct in stating that “salary generally is a reasonable proxy for skill level” and in claiming there is “a correlation between higher salaries and higher skill and Wage Levels.” That correlation, however, is weak. According to our analysis, three-quarters of the variation in salaries among H-1B winners cannot be explained by Wage Level, demonstrating that the proposed rule would fail to reliably identify the highest-skilled or most highly compensated applicants.,

While Wage Levels correlate well with wages within a particular occupation, wages between occupations can vary significantly, which the rule fails to take into account. This leads to some distortions that are obviously out of step with the intent of the rule. We offer a few examples:

- An exercise physiologist in Jacksonville, Florida, earning $55,000 per year would be classified as a Wage Level IV applicant and given four entries into the weighted lottery under the proposed rule. A software developer in San Francisco earning $155,000, with a salary classified as Level I, would only get one lottery entry. The hypothetical exercise physiologist earns 15 percent less than the median year-round, full-time American worker. The hypothetical software developer earns nearly 2.5 times the median year-round, full-time worker.

- In Huntsville, Alabama — a major hub of the American aerospace industry — a marriage and family therapist with a $65,000 salary offer (Level IV) will have twice the odds of winning an H-1B visa under the proposed weighted lottery as an aerospace engineer earning twice as much, $130,000 (Level II).

- In the Phoenix area, arguably at the center of the urgent race to build American semiconductor manufacturing capacity, an event planner earning $63,000 (Level IV) would be given twice as many lottery entries as an electrical engineer with a $115,000 (Level II) offer from Intel.

- The United States is facing fierce competition with China in artificial intelligence, yet a brilliant computer and information research scientist in Seattle with a $210,000 salary offer (Level II) plus stock options would have half the odds in the proposed weighted lottery as an acupuncturist in the same area making $105,000.

The reason for these unintended outcomes is that Wage Levels are specific to particular occupations in particular local labor markets. As a result, there are substantial overlaps in the distribution of actual salaries by Wage Level. We also find, for instance, that in fiscal year 2024:

- 20 percent of all successful Level I applicants earn more than the bottom 10 percent of Level IV winners.

- One-third of Level I winners earn more than the bottom decile of Level III winners.

- More than two-thirds — 68 percent — of all Level I H-1B winners in FY 2024 earned more than the bottom 10 percent of Level II winners.

- More than 30 percent of Level I, Level II, and Level III winners earned more than the bottom 10 percent of Level IV winners ($110,000).

We do wish to commend DHS for recognizing a major flaw in its 2021 H-1B selection final rule, which “effectively left little or no opportunity for the selection of lower Wage Level or entry-level workers, some of whom may still be highly skilled.” According to USCIS data, over 40 percent of individuals who are on a student visa are certified at Level 1 compared to less than one-fourth of non-student applicants. And yet, despite skewing younger and being disproportionately more likely than the average H-1B applicant to be certified at Level 1, international students earn higher median salaries because they are clustered in higher earning fields.

But while DHS recognizes that the 2021 final rule “did not capture the optimal approach” by effectively barring these highly skilled Level I applicants from the H-1B program, the agency is mistaken in its conclusion that conducting a weighted lottery based on DOL’s Wage Levels constitutes an improvement.

DHS states that the motivation behind pursuing a Wage-Level-based weighting of H-1B lottery registrations instead of the ranking method proposed in the 2021 rule was to “better ensure that initial H-1B visas and status grants would more likely go to the highest skilled or highest paid beneficiaries, while not effectively precluding those at lower Wage Levels.” Yet the new rule does nothing to distinguish those high-skilled, early-career Level I applicants with high salaries and sought-after skills.

An early-career pediatric surgeon in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, with a $230,000 salary stands the same chance of being awarded an H-1B visa under the proposed weighted lottery as a landscape architect in the same city earning $50,000. Alternatives that are instead based on actual proffered salary offers would account for such differences.

Section 2: The proposed rule would worsen IT outsourcers’ abuse of the H-1B program.

In addition to disfavoring younger employees with the greatest earning potential, the proposed rule also favors older, more tenured employees in relatively low-wage professions. As the Institute for Progress notes, the large IT outsourcing firms are generally certified for Wage Levels II and III. Boosting applicants’ weighted lottery odds based on their Wage Level, rather than their actual salaries, would end up increasing the number of H-1B visas awarded to these companies, which have a well-documented history of underpaying workers and discriminating against U.S. employees.

We find that large IT outsourcers would be awarded 7.4 percent more visas under the proposed rule than under current policy. Favoring these companies contradicts DHS’s stated goals of “disincentiviz[ing] the existing widespread use of the H-1B program to fill lower paid or lower skilled positions.”

The White House proclamation issued on September 19, 2025, also correctly noted that “some of the most prolific H-1B employers are now consistently IT outsourcing companies” and that “[d]omestic law enforcement agencies have identified and investigated H-1B-reliant outsourcing companies for engaging in visa fraud, conspiracy to launder money, conspiracy under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, and other illicit activities.” We strongly agree that abuse of the H-1B program by such companies is a major concern. It represents a waste of visas that should be awarded instead to workers, researchers, or entrepreneurs who bring skills and economic contributions that unambiguously benefit the United States. By awarding even more visas to companies abusing the status quo policy, the proposed rule fails to address these challenges and may even exacerbate them.

Section 3: The proposed weighted lottery would incentivize fraud, unlike a compensation-based ranking.

The proposed rule does not account for the new costs and enforcement challenges posed by using Wage Levels to weigh lottery applicants. Historically, unscrupulous employers have been found misclassifying their workers as employed in lower-paying occupations in order to underpay them or to evade program requirements. The proposed rule greatly worsens this incentive.

Because Wage Levels are assigned within occupations, not between them, employers will face stronger incentives to miscode or misclassify sponsored workers into slightly different occupations with lower Wage Level thresholds. Because distinct occupations with different average earnings frequently share similar job duties, core responsibilities, and required skills, these misclassifications will be too subtle and pervasive for enforcement agencies to detect in real time.

Under the status quo policy, DOL verifies Labor Condition Applications to ensure the information in them is accurate. DHS polices the boundaries of “specialty occupations.” The agency’s proposed rule would require much more intensive scrutiny around the bounds of particular occupations, requiring greater resources and raising the average time adjudicators must spend on each application.

Consider an example of a hypothetical software company in DeKalb County, Georgia, sponsoring a fresh computer science graduate for an H-1B visa with a mutually agreed-upon salary offer of $100,000. If the applicant is classified as a “software developer,” where Level I earnings in the area range from $82,000 to $105,000, the applicant will be classified as a Level I applicant with just a single lottery entry. But job descriptions are flexible, and the line between what constitutes a “software developer” and a “computer programmer,” a very similar occupation with lower wage requirements, is fuzzy. The employer could instead modify the on-paper job description to better fit that of a computer programmer, where the area’s Level I wages range from $70,000 to $90,000, reclassifying the applicant and doubling his odds of winning the weighted lottery.

This kind of manipulation will not just happen at lower Wage Levels. In Philadelphia, a company hiring a Data Warehousing Specialist with a $125,000 salary (Level II) could double its odds of winning the weighted lottery by slightly tweaking the job description to better fit that of a Database Administrator, where the worker would be classified as Level IV with four lottery entries.

Despite recent initiatives from DOL to increase scrutiny of H-1B employers suspected of abusing the program, these enforcement agencies lack the capacity to effectively identify all major instances of this type of fraud. Officials tasked with investigating and enforcing these types of violations lack subject matter expertise in the fields they are policing, severely limiting their ability to accurately differentiate between highly specialized occupations. These officials are not equipped to handle a surge of new misclassification cases that may result from the proposed rule, where they will be tasked with navigating highly technical distinctions between adjacent occupations, where differences in compensation can amount to tens of thousands of dollars.

While DHS is theoretically correct that some employers may respond to the change that gives higher Wage Level applicants better odds by “increas[ing] the proffered wage to increase the probability of getting its H-1B registration selected,” this possibility is undermined by the incentive for many to simply respond by misclassifying sponsored workers into occupations with lower Wage Level thresholds. This undercuts the stated purpose of the rule, which is to shift the use of the program to more skilled, well-paid applicants. The competitive pressures under a compensation-based, occupation agnostic ranking system, on the other hand, would accomplish this stated purpose of the rule by incentivizing employers to outbid one another with higher salary offers.

Section 4: Any reform to prioritize H-1B applicants by skill or merit should be occupation-agnostic.

The problems with the newly proposed rule by DHS, including its failure to prioritize the highest-skilled applicants and its incentive to commit fraud, ultimately stem from its prioritization of applicants in lower-paying occupations above those in higher-paying occupations. The proposed rule shifts the burden of labor-market competition into the opaque occupational classification system, where enforcement is weakest, rather than allowing wages themselves to function as the clear and objective signal of market demand. Even within the group of “specialty occupations” eligible for the H-1B visa, some occupations have wage distributions that sit much higher on the earnings spectrum than others. For example, the median engineering manager who won the H-1B lottery in FY 2024 had an average salary of $163,000, while the median public relations specialist earned $55,000.

As already explained, prioritizing applicants only according to where their wages lie on the distribution within their occupation leads to some obviously flawed outcomes. We believe that DHS should drop its use of occupation except insofar as it determines eligibility for the H-1B visa (i.e. whether an applicant is applying for a job in a “specialty occupation”).

Very high salaries are an indication that visa applicants are offering employers skills that are highly valuable to American companies and in short supply. Prioritizing applicants according to absolute earnings, rather than earnings relative to workers in the same occupation, is consistent with how DHS describes the purpose of the H-1B program: “to help U.S. employers fill labor shortages in positions requiring highly skilled or highly educated workers.” If firms find that a particular kind of worker offers critical, scarce skills, wages should rise, and such workers will be competitive in a system that allocates visas according to pay.

Prioritizing applicants according to absolute pay fixes the proposed rule’s incentive for employers to miscode or misclassify the workers they sponsor. The only way employers can improve their sponsored workers’ chance of being awarded a visa is to offer higher pay. This creates fairer competition for American workers, in line with the President’s September 19 proclamation. It also prioritizes applicants who possess skills so scarce and hard to find that employers are willing to pay substantially to acquire them.

Section 5: We propose two alternatives to the agency’s weighted lottery rule.

In this section, we offer two alternative, wage-based selection mechanisms for the agency to adopt in lieu of the proposed weighted lottery. The first, which we call a “lifetime expected earnings ranking,” would rank applicants according to projections of their future lifetime earnings, and accept them in descending order. The second, a compensation ranking, would accept H-1B applicants in descending order of pay.

Both options would be major improvements over the status quo and the agency’s proposal. We recommend the lifetime earnings ranking, though other immigration analysts prefer the compensation-based approach because of its relative simplicity. We present our analysis of both options below so that the agency can easily compare them.

As we will show, both options also accomplish the stated goals of the new rule more effectively than the agency’s proposal and, we believe, would yield much larger benefits to American communities, companies, workers, and the Treasury. In contrast to the agency’s proposals, both suggested alternatives would:

- Substantially raise the typical salary of new H-1B awardees;

- Dramatically reduce notorious IT outsourcers’ use of the H-1B program;

- Improve the H-1B’s net fiscal benefits to the United States; and

- Continue or improve retention of international students graduating from American universities.

Both options reconcile the 2021 rule’s goal of prioritizing the highest-paid, highest-skilled applicants and one of the goals of this year’s revisions: to ensure that highly-paid, early-career workers are not locked out of the program simply because of their job descriptions.

Below, we provide a detailed description of how each of these alternative policies would work in practice. Further, we use data on H-1B lottery winners from FY 2021 through FY 2024 from Bloomberg to construct simulations of each proposal alongside the agency’s proposal, the 2021 rule, and the status quo random lottery.

Option 1: Lifetime earnings ranking (maximizes economic and fiscal contribution)

Our primary recommendation is to rank applicants according to the net present value (NPV) of their expected lifetime earnings, estimated from their current salary offer and age. This ranking would select the workers who will make the maximum long-run economic and fiscal contributions to the United States. We suggest a ranking constructed according to the following steps:

- Adjust every applicant’s proffered salaries using the Regional Price Parity of the location of their worksite to account for differences in prices that may otherwise penalize applicants in lower cost-of-living labor markets.

- Project out every applicant’s expected earnings stream through age 65 according to the cross-sectional average earnings trajectory by age for private-sector workers with at least a four-year degree.

- Discount each applicant’s expected stream of future earnings by either 3 percent or 7 percent, as required by EO 14192 (“Unleasing Prosperity Through Deregulation”).

- Accept petitions in descending order of applicants’ NPV of future earnings until the regular cap of 65,000 is reached.

- Accept master’s cap-eligible petitions in descending order of NPV of future earnings until the supplemental 20,000-visa cap is reached.

This proposal would maximize the total long-run earnings (and therefore fiscal benefits) of each incoming cohort of new H-1B awardees. We believe that aiming to maximize the average lifetime contributions of each H-1B awardee makes sense for two reasons:

- First, Congress created the H-1B visa in 1990 as a dual-intent visa, meaning visa holders are allowed to seek permanent status while on their temporary visa. The intent of Congress was to create a bridge for high-wage talent to stay permanently.

- Second, most H-1B visa holders indeed intend to remain in the United States long-term. Recognizing these realities, it is therefore in the national interest to prioritize those workers who will make the largest economic and fiscal contributions over time, both during the period in which they are on the H-1B visa and beyond.

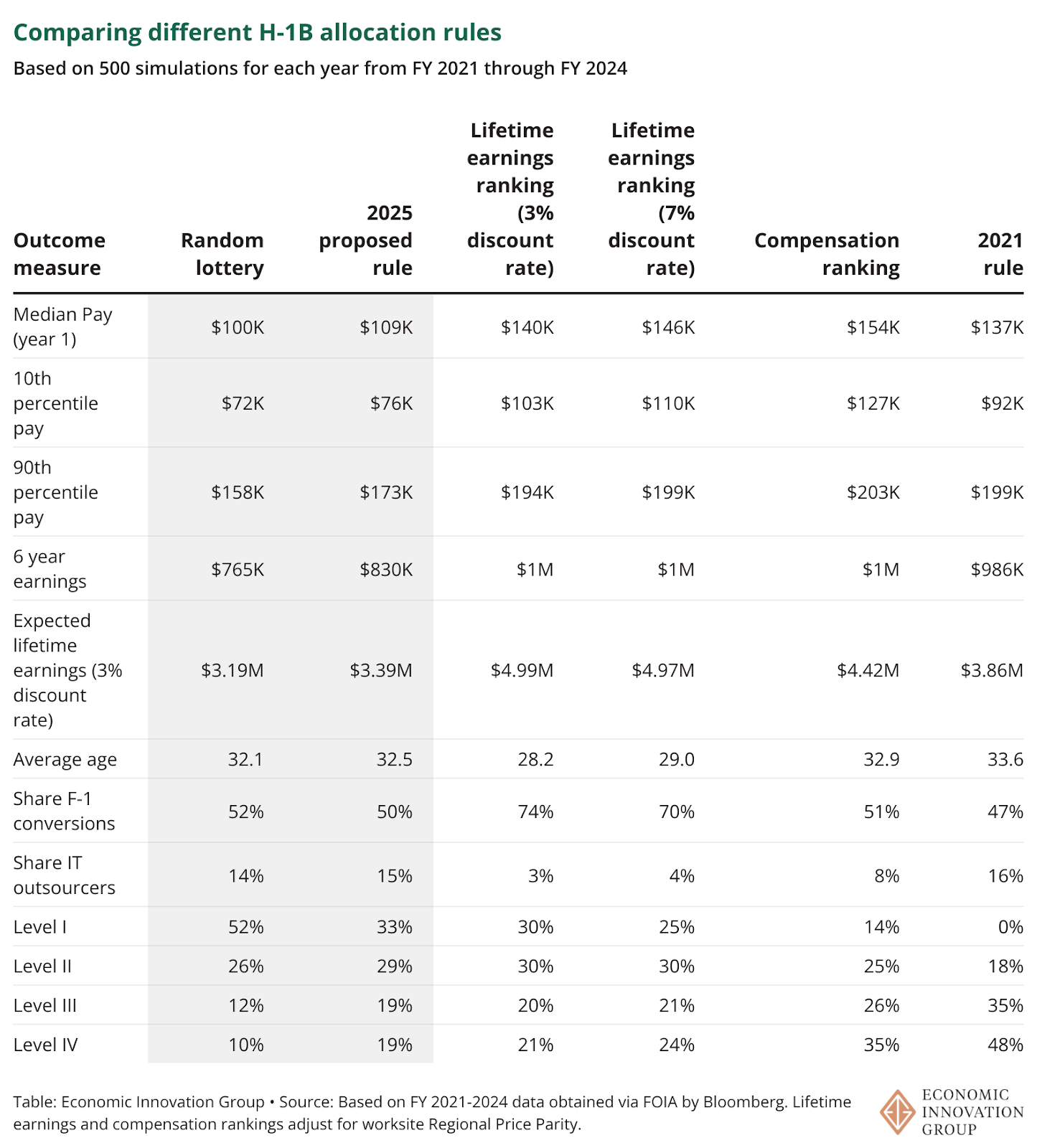

We find that a lifetime earnings ranking outperforms the agency’s proposal across a wide range of outcomes of interest. Under the lifetime earnings ranking, median pay would climb from $100,000 under the current random lottery to $140,000. In contrast, median earnings under the agency’s proposal would rise to just $109,000.

The expected lifetime earnings of a typical visa holder would also be much higher under a lifetime earnings ranking than either the status quo random lottery or the agency’s rules. Under a lifetime earnings ranking with a 3 percent discount rate, the typical worker awarded an H-1B would earn $5 million over their lifetime. Under the random lottery, the typical winner would earn just $3.2 million. Under the agency’s rule, lifetime earnings for the typical winner would rise modestly to $3.4 million. Over just the six years in which new H-1B awardees are on the visa, the typical new arrival under an expected lifetime earnings ranking would earn $315,000 more than under a random lottery and $251,000 more than under the agency’s proposal.

A lifetime earnings ranking does far better than the random lottery or the agency’s current proposal in reducing use of the H-1B visa by IT outsourcing companies. We estimate that a lifetime earnings ranking would reduce these companies’ use of the visa by 78 percent from the current random lottery. The agency’s rule would actually increase outsourcing companies’ use of the visa by 7.4 percent.

Finally, the lifetime earnings ranking would help retain many more international students who graduated from American colleges and universities. President Trump has repeatedly identified this as a problem that needs fixing. In June 2024, he said on the All In podcast, “Somebody graduates at the top of the class, they can’t even make a deal with the company because they don’t think they’re going to be able to stay in the country. That is going to end on day one.” Our proposed alternative to the agency’s rule would bring the country closer to the President’s goal of retaining more top international students who study at American schools. Under a lifetime earnings ranking, 74 percent of new H-1B awardees would be students adjusting from F-1 visa status. Under the random lottery, the share would be 52 percent, while under the agency’s proposed rule, the share would fall to 50 percent.

Option 2: Compensation Ranking (simpler, still highly effective)

The second option is a straightforward compensation ranking, which has been recommended by reform advocates across the political spectrum. Each applicant’s wages would be adjusted to account for the cost of living at their worksite, but would otherwise be ranked from highest to lowest. To meet the regular cap, the top 65,000 applicants with the highest (location-adjusted) salary offers would be granted a visa. The supplemental master’s cap would be met with the 20,000 highest-salaried applicants remaining who have a qualifying graduate degree.

Overall, the median salary for a new H-1B visa awardee would climb from less than $100,000 under the current random lottery to $154,000 under a compensation ranking. As noted earlier, under the agency’s proposal, the typical new H-1B would earn $109,000 in their first year, far less than under a compensation ranking.

Over their lifetimes, H-1B awardees under a compensation-based ranking would earn $4.4 million over their working lives, compared to $3.4 million under the agency’s proposal and $3.2 million under the random lottery. Over six years — equivalent to two full terms of an H-1B visa — the typical arrival under a compensation ranking system would earn $359,000 more than the average winner under the random lottery and $295,000 more than under the agency’s proposed rule.

At the same time, the number of visas awarded to IT outsourcers would fall by 41 percent under a compensation-based ranking, while it would rise 7.4 percent under the agency’s proposal.

Under a compensation ranking, 51 percent of new, cap-subject H-1B visas would be awarded to applicants adjusting from an F-1 status. By comparison, that share would be 50 percent under the proposed rule.

Applying a weighted lottery to either policy recommendation

While a system that ranks applicants based on lifetime expected earnings or proffered salaries are both superior to one that selects applicants based on a weighted lottery, DHS can greatly minimize the negative consequences of the proposed rule even if the agency insists on maintaining the lottery framework.

As written, the proposed rule’s use of Wage Levels would not significantly raise the average skill level of new winners and in fact would reward outsourcing companies that have long abused the program. This is not the right way to design a weighted lottery.

A weighted lottery, while not ideal, should instead base applicants’ odds of winning on where they fall within the whole distribution of applicants’ expected lifetime earnings or salary offers.

This approach would be superior to the agency’s current proposal of granting each applicant a certain number of lottery entries based on their within-occupation Wage Level. As we have shown, this mistake significantly undercuts the average pay of the typical H-1B awardee and will significantly reduce the amount of tax revenue the Treasury derives from the earnings of each winner over their working lives.

Any weighted lottery should furthermore give much greater relative odds to top applicants than the agency’s current proposal, such that the very highest-paid applicants have at least a 90 percent chance of being awarded a visa. Under the current proposal, top applicants (who are poorly identified because of the agency’s use of Wage Levels) have less than a 70 percent chance of winning the weighted lottery. Those odds are too low.

Comparing the alternatives

Using data on H-1B lottery winners obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request from Bloomberg, we simulate the effects of different H-1B allocation mechanisms on outcomes that include pay, F-1 conversions, average age, and expected future earnings. Using the winners of the first (“regular cap”) random lottery, whose winners are representative of the overall applicant pool, we simulate applicant pools and apply different policies to allocate 85,000 H-1B visas annually. For more information on the methodology behind these simulations, see the appendix.

Using these simulations, we compare the following policy alternatives:

- The status quo random lottery

- DHS’ current proposed rule

- A lifetime earnings ranking, assuming a 3 percent discount rate

- A lifetime earnings ranking, assuming a 7 percent discount rate

- A compensation-based ranking

- DHS’ 2021 final rule

We find lifetime earnings and compensation-based rankings outperform the agency’s current proposal, its 2021 rule, and the random lottery on selecting for the highest-skilled, highest-paid applicants; retaining international students; and reducing abuse from IT outsourcing firms.

Conclusion

DHS has correctly identified the fundamental problem with the H-1B program: relying on a pure lottery system to allocate visas. Unfortunately, the agency’s proposed weighted lottery would not achieve its stated intent to shift the H-1B program to higher-paying, higher-skilled applicants. Instead, it will boost the number of visas going to IT outsourcing companies that have long drawn bipartisan scrutiny. It would not provide certainty to very highly-paid applicants, still subjecting them to a lottery. Nor would the proposed rule accomplish what it seeks to do in revising the 2021 rule: providing a path for exceptional early-career talent.

We strongly urge the agency to revise its proposal and adopt either an expected lifetime earnings or compensation-based ranking to prioritize applicants. As our estimates show, this will prioritize more highly-skilled applicants who yield greater economic benefits to the United States than the agency’s current proposal.

Sincerely,

Sam Peak

Manager, Labor and Mobility Policy

Connor O’Brien

Research Analyst, Innovation and Industrial Policy

Jiaxin He

Research Assistant

Appendix: Our methodology

1. Identifying salaries and Wage Levels of H1-B lottery winners

We link H-1B lottery winners from FY 2021 to FY 2024, obtained from Bloomberg, with Labor Condition Application (LCA) disclosure data from FY 2015 to FY 2024 using Department of Labor case IDs, accounting for the multi-year processing time of LCAs. Entries censored under sections (b)(3), (b)(6), or (b)(7)(C) of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) are excluded. Entries listing applicants under 18 years of age are presumed to be erroneous, as the H-1B program requires at least a bachelor’s degree, and are therefore excluded from the analysis.

To correct for missing values and reporting errors in H-1B annual wages recorded on USCIS Form I-129, we proceed as follows:

- We first assume that annual earnings reported between $10 and $500 represent hourly wages and annualize them based on the worker’s full- or part-time status.

- For wage entries below $10 or between $500 and $30,000, we substitute the values with the corresponding LCA-reported annual wages whenever available.

- If an I-129 wage falls within the top 1 percent of entries and exceeds the LCA wage by more than a factor of ten, we infer a misplaced decimal point and divide the I-129 wage by the power of ten closest to the I-129-to-LCA wage ratio. Similarly, top 1 percent I-129 wages that are more than twice their corresponding LCA wages are replaced with the LCA values.

- When I-129 wages fall between one-tenth and 95 percent of their respective LCA wages, they are also replaced with the LCA values, provided that the LCA wages are below $1 million or below the LCA’s reported upper bound, whichever is smaller.

- Two records reporting annual earnings above $8 million are discarded due to apparent irregularities.

Since the same individual may file multiple petitions for different worksites, a loophole that was particularly exploited in FY 2024, we retain only one entry from each group of records in which multiple H-1B petitions were filed under the same LCA case and share identical demographic, educational, and immigration characteristics. Although this filter is not perfect, it provides the best available means of ensuring that each H-1B petition corresponds to a unique worker.

To assign H-1B petitions to metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), we use the crosswalk provided by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to link each I-129 worksite ZIP code to the county with which at least 90 percent of the ZIP code’s land area overlaps. Entries that cannot be matched through this method are instead assigned to counties using coordinates geocoded from the listed addresses. Records without valid geocoding are assigned to the LCA worksite county. Finally, counties (or towns, in the case of New England states) are merged into MSAs using the geographic crosswalk provided by the Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC). Three entries lacking identifiable MSAs are excluded.

Most H-1B petitions already include Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) occupation codes in their corresponding LCA records. We crosswalk all existing SOC codes to the most recent vintage (2018). For petitions missing SOC codes, we first apply a string similarity algorithm to match their Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) codes and applicant-entered job titles to SOC codes. We then use a machine learning model trained on entries with valid SOCs to predict missing occupational codes based on the petitioner’s firm name, degree field, and self-reported job title. Remaining entries are retained if they contain valid LCA Wage Levels, which drops around one thousand entries.

Because we only have access to 2024–2025 OFLC Wage Level data due to the government shutdown, we adjust 2021–2023 wages to 2024 levels for Wage Level identification purposes only, using the growth rates of mean wages for the corresponding MSA–SOC combinations from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES). Records with missing or censored OES mean wages are instead adjusted to 2024 dollars using the PCE inflation rate. OFLC Level floors for each metropolitan area and occupation are applied wherever available. Wages below the Level I threshold are treated as Level I, while those lacking OFLC information are substituted with LCA-reported Wage Levels.

To account for cost-of-living differences across the visa applicants’ worksites, we further adjust wages using state-level Regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Wages from 2021 to 2023 are adjusted using each year’s corresponding RPP, while 2024 wages use the 2023 RPP values, the most recent available data.

In total, we identify around 373,000 H-1B petitions from lottery winners from FY2021 to FY2024 with valid wage, metropolitan area, occupation, and Wage Level information.

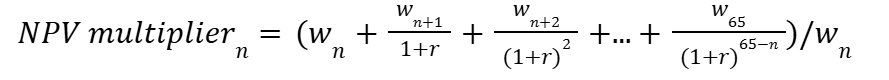

2. Projecting Net Present Value (NPV) of H1-B applicants’ expected lifetime earnings

To estimate the lifetime earnings of each year’s H-1B cohort, we begin with mean wages by age for all private-sector wage and salary workers holding at least a bachelor’s degree, as reported in the most recent five-year American Community Survey (ACS) from the U.S. Census Bureau. The wage universe is restricted to reflect the characteristics of H-1B applicants — skilled, college-educated workers employed in the private sector.

For each age between 22 and 65, we discount the ACS cross-sectional mean wages for subsequent ages by either 3 percent or 7 percent, as specified by Executive Order 14192, and sum the discounted values to calculate the expected NPV of earnings. Finally, we divide the NPV of each age’s projected earnings stream by the corresponding mean wage to derive the expected lifetime earnings multiplier.

For workers with age n, discount rate r, and ACS cross-sectional mean wage w, the equation for NPV multiplier is as follows:

We assign the NPV multiplier for 22-year-olds to all age groups younger than 22, and the multiplier for 59-year-olds to all ages above 59. Because H-1B visas require applicants to hold at least a bachelor’s degree, nearly all applicants are 22 or older. The few 20- and 21-year-olds in the sample are likely freshly graduated from college and are therefore treated the same as the 22-year-old recent graduates. Conversely, H-1B awardees are expected to work for two full visa terms (six years), so individuals between 60 and 65 can reasonably be assumed to remain employed for at least six additional years. Since most U.S. workers begin retiring around age 65, ACS cross-sectional mean wages beyond that age are not representative of actual late-career earnings. Given these limitations, the best practice is to apply the same multiplier used for 60- to 65-year-olds to those continuing to work past 65.

Our preferred proposal aims to maximize the total long-run earnings of H-1B awardees. To do so, we multiply each applicant’s wage by the NPV multiplier corresponding to their age and rank the resulting products in descending order to allocate visas under the regular (65,000) and graduate (20,000) caps.

3. Simulating different H1-B selection schemes using synthetic samples

The strict randomness of the current H1-B lottery for the regular lottery cap makes the lottery winners a representative sample of the universe of all workers who entered the lottery.

Using the H-1B lottery winners from each fiscal year, after applying the data cleaning procedures outlined above, we first subset the sample to those who answered “B” in Section 3, Question 1 of Form I-129, indicating selection under the uncapped 65,000 quota. Among these uncapped winners, we then retain only approved petitions to calculate the approval rate. Since the lottery is random, we assume that all entrants faced the same approval probability as the uncapped sample and simulate only those whose applications would have been approved.

Among the uncapped lottery winners whose petitions were approved, we calculate the share of individuals holding master’s, Ph.D., or professional graduate degrees. This share is assumed to represent the proportion of graduate degree holders among all lottery entrants, although it may be underestimated due to missing education data in some I-129 records. With this estimate, we derive the number of H-1B lottery entrants eligible for the graduate cap and those who are not.

Combining the approved graduate degree holders among the uncapped lottery winners with the capped winners (those who answered “M” in Section 3, Question 1 of Form I-129), we obtain a complete sample of graduate degree holders. We then draw randomly with replacement from this group up to the estimated number of graduate-cap entrants. Similarly, we perform random draws with replacement from the non-graduate degree holders among the regular cap’s lottery winners up to the estimated number of bachelor’s-level entrants. Combining the regular cap-eligible and ineligible synthetic H-1B lottery entrants produces a synthetic dataset of all H-1B applicants for a given year who would have been approved had they been selected for a visa.

We generate the synthetic H-1B applicant dataset 500 times and apply the following selection procedures to obtain summary statistics for potential H-1B awardees:

- The current, random lottery system

- The proposed Wage-Level-weighted lottery

- The 2021 Wage-Level-based ranking and lottery

- Ranking by RPP-adjusted compensation alone

- Ranking by lifetime earnings NPV using 3 percent and 7 percent discount rates

All wage summaries for FY 2021–FY 2023 are adjusted to 2024 dollars.

View the Github with code for replicating this analysis here.

Notes

On October 24, 2025, the Economic Innovation Group submitted a comment letter to the Department of Homeland Security in response to its proposed rule, Weighted Selection Process for Registrants and Petitioners Seeking To File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions. The letter provides detailed recommendations and proposes alternative policies designed to more effectively prioritize and select the most highly skilled workers for the H-1B program.

Chief, Business and Foreign Workers Division

Office of Policy and Strategy

Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

5900 Capital Gateway Drive, Camp Springs, MD 20746

Phone: 240-721-3000

RE: DHS Docket No. USCIS-2025-0040, Weighted Selection Process for Registrants and Petitioners Seeking To File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions

Dear Sir or Madam:

The Economic Innovation Group (EIG) is a bipartisan economic research and advocacy organization dedicated to fostering a more dynamic and entrepreneurial American economy. We commend the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for its intention to overhaul the H-1B lottery in a manner that “would favor the allocation of H-1B visas to higher skilled and higher paid aliens.”[1] Unfortunately, the agency’s current proposal would fail to accomplish its stated goals and in fact would place them further out of reach.

Instead of prioritizing new H-1B applicants according to pay, the proposed rule gives greater weight to those applicants whose jobs are tagged with higher “Wage Levels,” as defined by the Department of Labor. These Wage Levels are only weakly correlated with actual salary or proffered wages. The rule attempts to prioritize applicants whose wages are high relative to other workers in their same occupation and labor market — but it does not prioritize between occupations or labor markets. The result is that the rule would prioritize many lower-skilled, lower-paid workers over other applicants with much higher salaries. This is a mistake that deeply undermines the purpose of the rule, which is to prioritize top talent with skills that are both scarce and in high demand.

Beyond the proposed rule’s failure to prioritize the highest-earning applicants, the proposal suffers from three additional problems:

In this comment letter, we elaborate on the flaws of the proposed rule and offer a better, occupation-agnostic system for DHS to prioritize simultaneously submitted applications. Our proposed alternative would lead to the expected median annual wage of H-1Bs being $31,000 (29 percent) higher than the current rule and $40,000 (41 percent) higher than the status quo random lottery.[3] While the proposed rule would lead to more IT outsourcers winning H-1B visas than the status quo lottery, our proposal reduces these notorious companies’ use of the H-1B by 80 percent.

Compared to the proposed rule, our proposed alternative improves the selection and retention of exceptional early-career workers and yields larger net fiscal benefits to the United States than either the proposed rule or current policy.

Section 1: The Proposed Rule Misidentifies Talent and Will Systematically Disadvantage Top Earners.

DHS is correct in stating that “salary generally is a reasonable proxy for skill level” and in claiming there is “a correlation between higher salaries and higher skill and Wage Levels.”[4] That correlation, however, is weak. According to our analysis, three-quarters of the variation in salaries among H-1B winners cannot be explained by Wage Level, demonstrating that the proposed rule would fail to reliably identify the highest-skilled or most highly compensated applicants.[5],[6]

While Wage Levels correlate well with wages within a particular occupation, wages between occupations can vary significantly, which the rule fails to take into account. This leads to some distortions that are obviously out of step with the intent of the rule. We offer a few examples:

The reason for these unintended outcomes is that Wage Levels are specific to particular occupations in particular local labor markets. As a result, there are substantial overlaps in the distribution of actual salaries by Wage Level. We also find, for instance, that in fiscal year 2024:

We do wish to commend DHS for recognizing a major flaw in its 2021 H-1B selection final rule,[9] which “effectively left little or no opportunity for the selection of lower Wage Level or entry-level workers, some of whom may still be highly skilled.”[10] According to USCIS data, over 40 percent of individuals who are on a student visa are certified at Level 1 compared to less than one-fourth of non-student applicants. And yet, despite skewing younger and being disproportionately more likely than the average H-1B applicant to be certified at Level 1, international students earn higher median salaries because they are clustered in higher earning fields.[11]

But while DHS recognizes that the 2021 final rule “did not capture the optimal approach”[12] by effectively barring these highly skilled Level I applicants from the H-1B program, the agency is mistaken in its conclusion that conducting a weighted lottery based on DOL’s Wage Levels constitutes an improvement.

DHS states that the motivation behind pursuing a Wage-Level-based weighting of H-1B lottery registrations instead of the ranking method proposed in the 2021 rule was to “better ensure that initial H-1B visas and status grants would more likely go to the highest skilled or highest paid beneficiaries, while not effectively precluding those at lower Wage Levels.”[13] Yet the new rule does nothing to distinguish those high-skilled, early-career Level I applicants with high salaries and sought-after skills.

An early-career pediatric surgeon in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, with a $230,000 salary stands the same chance of being awarded an H-1B visa under the proposed weighted lottery as a landscape architect in the same city earning $50,000.[14] Alternatives that are instead based on actual proffered salary offers would account for such differences.

Section 2: The proposed rule would worsen IT outsourcers’ abuse of the H-1B program.

In addition to disfavoring younger employees with the greatest earning potential, the proposed rule also favors older, more tenured employees in relatively low-wage professions. As the Institute for Progress notes, the large IT outsourcing firms are generally certified for Wage Levels II and III.[15] Boosting applicants’ weighted lottery odds based on their Wage Level, rather than their actual salaries, would end up increasing the number of H-1B visas awarded to these companies, which have a well-documented history of underpaying workers and discriminating against U.S. employees.[16]

We find that large IT outsourcers would be awarded 7.4 percent more visas under the proposed rule than under current policy.[17] Favoring these companies contradicts DHS’s stated goals of “disincentiviz[ing] the existing widespread use of the H-1B program to fill lower paid or lower skilled positions.”[18]

The White House proclamation issued on September 19, 2025, also correctly noted that “some of the most prolific H-1B employers are now consistently IT outsourcing companies” and that “[d]omestic law enforcement agencies have identified and investigated H-1B-reliant outsourcing companies for engaging in visa fraud, conspiracy to launder money, conspiracy under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, and other illicit activities.”[19] We strongly agree that abuse of the H-1B program by such companies is a major concern. It represents a waste of visas that should be awarded instead to workers, researchers, or entrepreneurs who bring skills and economic contributions that unambiguously benefit the United States. By awarding even more visas to companies abusing the status quo policy, the proposed rule fails to address these challenges and may even exacerbate them.

Section 3: The proposed weighted lottery would incentivize fraud, unlike a compensation-based ranking.

The proposed rule does not account for the new costs and enforcement challenges posed by using Wage Levels to weigh lottery applicants. Historically, unscrupulous employers have been found misclassifying their workers as employed in lower-paying occupations in order to underpay them or to evade program requirements.[20] The proposed rule greatly worsens this incentive.

Because Wage Levels are assigned within occupations, not between them, employers will face stronger incentives to miscode or misclassify sponsored workers into slightly different occupations with lower Wage Level thresholds. Because distinct occupations with different average earnings frequently share similar job duties, core responsibilities, and required skills, these misclassifications will be too subtle and pervasive for enforcement agencies to detect in real time.

Under the status quo policy, DOL verifies Labor Condition Applications to ensure the information in them is accurate. DHS polices the boundaries of “specialty occupations.” The agency’s proposed rule would require much more intensive scrutiny around the bounds of particular occupations, requiring greater resources and raising the average time adjudicators must spend on each application.

Consider an example of a hypothetical software company in DeKalb County, Georgia, sponsoring a fresh computer science graduate for an H-1B visa with a mutually agreed-upon salary offer of $100,000. If the applicant is classified as a “software developer,” where Level I earnings in the area range from $82,000 to $105,000, the applicant will be classified as a Level I applicant with just a single lottery entry.[21] But job descriptions are flexible, and the line between what constitutes a “software developer” and a “computer programmer,” a very similar occupation with lower wage requirements, is fuzzy. The employer could instead modify the on-paper job description to better fit that of a computer programmer, where the area’s Level I wages range from $70,000 to $90,000, reclassifying the applicant and doubling his odds of winning the weighted lottery.

This kind of manipulation will not just happen at lower Wage Levels. In Philadelphia, a company hiring a Data Warehousing Specialist with a $125,000 salary (Level II) could double its odds of winning the weighted lottery by slightly tweaking the job description to better fit that of a Database Administrator, where the worker would be classified as Level IV with four lottery entries.[22]

Despite recent initiatives from DOL[23] to increase scrutiny of H-1B employers suspected of abusing the program, these enforcement agencies lack the capacity to effectively identify all major instances of this type of fraud. Officials tasked with investigating and enforcing these types of violations lack subject matter expertise in the fields they are policing, severely limiting their ability to accurately differentiate between highly specialized occupations. These officials are not equipped to handle a surge of new misclassification cases that may result from the proposed rule, where they will be tasked with navigating highly technical distinctions between adjacent occupations, where differences in compensation can amount to tens of thousands of dollars.

While DHS is theoretically correct that some employers may respond to the change that gives higher Wage Level applicants better odds by “increas[ing] the proffered wage to increase the probability of getting its H-1B registration selected,”[24] this possibility is undermined by the incentive for many to simply respond by misclassifying sponsored workers into occupations with lower Wage Level thresholds. This undercuts the stated purpose of the rule, which is to shift the use of the program to more skilled, well-paid applicants. The competitive pressures under a compensation-based, occupation agnostic ranking system, on the other hand, would accomplish this stated purpose of the rule by incentivizing employers to outbid one another with higher salary offers.

Section 4: Any reform to prioritize H-1B applicants by skill or merit should be occupation-agnostic.

The problems with the newly proposed rule by DHS, including its failure to prioritize the highest-skilled applicants and its incentive to commit fraud, ultimately stem from its prioritization of applicants in lower-paying occupations above those in higher-paying occupations. The proposed rule shifts the burden of labor-market competition into the opaque occupational classification system, where enforcement is weakest, rather than allowing wages themselves to function as the clear and objective signal of market demand. Even within the group of “specialty occupations” eligible for the H-1B visa, some occupations have wage distributions that sit much higher on the earnings spectrum than others. For example, the median engineering manager who won the H-1B lottery in FY 2024 had an average salary of $163,000, while the median public relations specialist earned $55,000.[25]

As already explained, prioritizing applicants only according to where their wages lie on the distribution within their occupation leads to some obviously flawed outcomes. We believe that DHS should drop its use of occupation except insofar as it determines eligibility for the H-1B visa (i.e. whether an applicant is applying for a job in a “specialty occupation”).

Very high salaries are an indication that visa applicants are offering employers skills that are highly valuable to American companies and in short supply. Prioritizing applicants according to absolute earnings, rather than earnings relative to workers in the same occupation, is consistent with how DHS describes the purpose of the H-1B program: “to help U.S. employers fill labor shortages in positions requiring highly skilled or highly educated workers.” If firms find that a particular kind of worker offers critical, scarce skills, wages should rise, and such workers will be competitive in a system that allocates visas according to pay.

Prioritizing applicants according to absolute pay fixes the proposed rule’s incentive for employers to miscode or misclassify the workers they sponsor. The only way employers can improve their sponsored workers’ chance of being awarded a visa is to offer higher pay. This creates fairer competition for American workers, in line with the President’s September 19 proclamation. It also prioritizes applicants who possess skills so scarce and hard to find that employers are willing to pay substantially to acquire them.

Section 5: We propose two alternatives to the agency’s weighted lottery rule.

In this section, we offer two alternative, wage-based selection mechanisms for the agency to adopt in lieu of the proposed weighted lottery. The first, which we call a “lifetime expected earnings ranking,” would rank applicants according to projections of their future lifetime earnings, and accept them in descending order. The second, a compensation ranking, would accept H-1B applicants in descending order of pay.

Both options would be major improvements over the status quo and the agency’s proposal. We recommend the lifetime earnings ranking, though other immigration analysts prefer the compensation-based approach because of its relative simplicity. We present our analysis of both options below so that the agency can easily compare them.

As we will show, both options also accomplish the stated goals of the new rule more effectively than the agency’s proposal and, we believe, would yield much larger benefits to American communities, companies, workers, and the Treasury. In contrast to the agency’s proposals, both suggested alternatives would:

Both options reconcile the 2021 rule’s goal of prioritizing the highest-paid, highest-skilled applicants and one of the goals of this year’s revisions: to ensure that highly-paid, early-career workers are not locked out of the program simply because of their job descriptions.

Below, we provide a detailed description of how each of these alternative policies would work in practice. Further, we use data on H-1B lottery winners from FY 2021 through FY 2024 from Bloomberg to construct simulations of each proposal alongside the agency’s proposal, the 2021 rule, and the status quo random lottery.

Option 1: Lifetime earnings ranking (maximizes economic and fiscal contribution)

Our primary recommendation is to rank applicants according to the net present value (NPV) of their expected lifetime earnings, estimated from their current salary offer and age. This ranking would select the workers who will make the maximum long-run economic and fiscal contributions to the United States. We suggest a ranking constructed according to the following steps:

This proposal would maximize the total long-run earnings (and therefore fiscal benefits) of each incoming cohort of new H-1B awardees. We believe that aiming to maximize the average lifetime contributions of each H-1B awardee makes sense for two reasons:

We find that a lifetime earnings ranking outperforms the agency’s proposal across a wide range of outcomes of interest. Under the lifetime earnings ranking, median pay would climb from $100,000 under the current random lottery to $140,000. In contrast, median earnings under the agency’s proposal would rise to just $109,000.[29]

The expected lifetime earnings of a typical visa holder would also be much higher under a lifetime earnings ranking than either the status quo random lottery or the agency’s rules. Under a lifetime earnings ranking with a 3 percent discount rate, the typical worker awarded an H-1B would earn $5 million over their lifetime. Under the random lottery, the typical winner would earn just $3.2 million. Under the agency’s rule, lifetime earnings for the typical winner would rise modestly to $3.4 million. Over just the six years in which new H-1B awardees are on the visa, the typical new arrival under an expected lifetime earnings ranking would earn $315,000 more than under a random lottery and $251,000 more than under the agency’s proposal.[30]

A lifetime earnings ranking does far better than the random lottery or the agency’s current proposal in reducing use of the H-1B visa by IT outsourcing companies. We estimate that a lifetime earnings ranking would reduce these companies’ use of the visa by 78 percent from the current random lottery. The agency’s rule would actually increase outsourcing companies’ use of the visa by 7.4 percent.

Finally, the lifetime earnings ranking would help retain many more international students who graduated from American colleges and universities. President Trump has repeatedly identified this as a problem that needs fixing. In June 2024, he said on the All In podcast, “Somebody graduates at the top of the class, they can’t even make a deal with the company because they don’t think they’re going to be able to stay in the country. That is going to end on day one.”[31] Our proposed alternative to the agency’s rule would bring the country closer to the President’s goal of retaining more top international students who study at American schools. Under a lifetime earnings ranking, 74 percent of new H-1B awardees would be students adjusting from F-1 visa status. Under the random lottery, the share would be 52 percent, while under the agency’s proposed rule, the share would fall to 50 percent.[32]

Option 2: Compensation Ranking (simpler, still highly effective)

The second option is a straightforward compensation ranking, which has been recommended by reform advocates across the political spectrum. Each applicant’s wages would be adjusted to account for the cost of living at their worksite, but would otherwise be ranked from highest to lowest. To meet the regular cap, the top 65,000 applicants with the highest (location-adjusted) salary offers would be granted a visa. The supplemental master’s cap would be met with the 20,000 highest-salaried applicants remaining who have a qualifying graduate degree.

Overall, the median salary for a new H-1B visa awardee would climb from less than $100,000 under the current random lottery to $154,000 under a compensation ranking. As noted earlier, under the agency’s proposal, the typical new H-1B would earn $109,000 in their first year, far less than under a compensation ranking.

Over their lifetimes, H-1B awardees under a compensation-based ranking would earn $4.4 million over their working lives, compared to $3.4 million under the agency’s proposal and $3.2 million under the random lottery. Over six years — equivalent to two full terms of an H-1B visa — the typical arrival under a compensation ranking system would earn $359,000 more than the average winner under the random lottery and $295,000 more than under the agency’s proposed rule.

At the same time, the number of visas awarded to IT outsourcers would fall by 41 percent under a compensation-based ranking, while it would rise 7.4 percent under the agency’s proposal.

Under a compensation ranking, 51 percent of new, cap-subject H-1B visas would be awarded to applicants adjusting from an F-1 status. By comparison, that share would be 50 percent under the proposed rule.[33]

Applying a weighted lottery to either policy recommendation

While a system that ranks applicants based on lifetime expected earnings or proffered salaries are both superior to one that selects applicants based on a weighted lottery, DHS can greatly minimize the negative consequences of the proposed rule even if the agency insists on maintaining the lottery framework.

As written, the proposed rule’s use of Wage Levels would not significantly raise the average skill level of new winners and in fact would reward outsourcing companies that have long abused the program. This is not the right way to design a weighted lottery.

A weighted lottery, while not ideal, should instead base applicants’ odds of winning on where they fall within the whole distribution of applicants’ expected lifetime earnings or salary offers.

This approach would be superior to the agency’s current proposal of granting each applicant a certain number of lottery entries based on their within-occupation Wage Level. As we have shown, this mistake significantly undercuts the average pay of the typical H-1B awardee and will significantly reduce the amount of tax revenue the Treasury derives from the earnings of each winner over their working lives.

Any weighted lottery should furthermore give much greater relative odds to top applicants than the agency’s current proposal, such that the very highest-paid applicants have at least a 90 percent chance of being awarded a visa. Under the current proposal, top applicants (who are poorly identified because of the agency’s use of Wage Levels) have less than a 70 percent chance of winning the weighted lottery.[34] Those odds are too low.

Comparing the alternatives

Using data on H-1B lottery winners obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request from Bloomberg, we simulate the effects of different H-1B allocation mechanisms on outcomes that include pay, F-1 conversions, average age, and expected future earnings. Using the winners of the first (“regular cap”) random lottery, whose winners are representative of the overall applicant pool, we simulate applicant pools and apply different policies to allocate 85,000 H-1B visas annually. For more information on the methodology behind these simulations, see the appendix.

Using these simulations, we compare the following policy alternatives:

We find lifetime earnings and compensation-based rankings outperform the agency’s current proposal, its 2021 rule, and the random lottery on selecting for the highest-skilled, highest-paid applicants; retaining international students; and reducing abuse from IT outsourcing firms.

Conclusion

DHS has correctly identified the fundamental problem with the H-1B program: relying on a pure lottery system to allocate visas. Unfortunately, the agency’s proposed weighted lottery would not achieve its stated intent to shift the H-1B program to higher-paying, higher-skilled applicants. Instead, it will boost the number of visas going to IT outsourcing companies that have long drawn bipartisan scrutiny. It would not provide certainty to very highly-paid applicants, still subjecting them to a lottery. Nor would the proposed rule accomplish what it seeks to do in revising the 2021 rule: providing a path for exceptional early-career talent.

We strongly urge the agency to revise its proposal and adopt either an expected lifetime earnings or compensation-based ranking to prioritize applicants. As our estimates show, this will prioritize more highly-skilled applicants who yield greater economic benefits to the United States than the agency’s current proposal.

Sincerely,

Sam Peak

Manager, Labor and Mobility Policy

Connor O’Brien

Research Analyst, Innovation and Industrial Policy

Jiaxin He

Research Assistant

Appendix: Our methodology

1. Identifying salaries and Wage Levels of H1-B lottery winners

We link H-1B lottery winners from FY 2021 to FY 2024, obtained from Bloomberg, with Labor Condition Application (LCA) disclosure data from FY 2015 to FY 2024 using Department of Labor case IDs, accounting for the multi-year processing time of LCAs. Entries censored under sections (b)(3), (b)(6), or (b)(7)(C) of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) are excluded. Entries listing applicants under 18 years of age are presumed to be erroneous, as the H-1B program requires at least a bachelor’s degree, and are therefore excluded from the analysis.

To correct for missing values and reporting errors in H-1B annual wages recorded on USCIS Form I-129, we proceed as follows:

Since the same individual may file multiple petitions for different worksites, a loophole that was particularly exploited in FY 2024, we retain only one entry from each group of records in which multiple H-1B petitions were filed under the same LCA case and share identical demographic, educational, and immigration characteristics. Although this filter is not perfect, it provides the best available means of ensuring that each H-1B petition corresponds to a unique worker.

To assign H-1B petitions to metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), we use the crosswalk provided by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to link each I-129 worksite ZIP code to the county with which at least 90 percent of the ZIP code’s land area overlaps. Entries that cannot be matched through this method are instead assigned to counties using coordinates geocoded from the listed addresses. Records without valid geocoding are assigned to the LCA worksite county. Finally, counties (or towns, in the case of New England states) are merged into MSAs using the geographic crosswalk provided by the Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC). Three entries lacking identifiable MSAs are excluded.

Most H-1B petitions already include Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) occupation codes in their corresponding LCA records. We crosswalk all existing SOC codes to the most recent vintage (2018). For petitions missing SOC codes, we first apply a string similarity algorithm to match their Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT) codes and applicant-entered job titles to SOC codes. We then use a machine learning model trained on entries with valid SOCs to predict missing occupational codes based on the petitioner’s firm name, degree field, and self-reported job title. Remaining entries are retained if they contain valid LCA Wage Levels, which drops around one thousand entries.

Because we only have access to 2024–2025 OFLC Wage Level data due to the government shutdown, we adjust 2021–2023 wages to 2024 levels for Wage Level identification purposes only, using the growth rates of mean wages for the corresponding MSA–SOC combinations from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES). Records with missing or censored OES mean wages are instead adjusted to 2024 dollars using the PCE inflation rate. OFLC Level floors for each metropolitan area and occupation are applied wherever available. Wages below the Level I threshold are treated as Level I, while those lacking OFLC information are substituted with LCA-reported Wage Levels.

To account for cost-of-living differences across the visa applicants’ worksites, we further adjust wages using state-level Regional Price Parities (RPPs) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Wages from 2021 to 2023 are adjusted using each year’s corresponding RPP, while 2024 wages use the 2023 RPP values, the most recent available data.

In total, we identify around 373,000 H-1B petitions from lottery winners from FY2021 to FY2024 with valid wage, metropolitan area, occupation, and Wage Level information.

2. Projecting Net Present Value (NPV) of H1-B applicants’ expected lifetime earnings

To estimate the lifetime earnings of each year’s H-1B cohort, we begin with mean wages by age for all private-sector wage and salary workers holding at least a bachelor’s degree, as reported in the most recent five-year American Community Survey (ACS) from the U.S. Census Bureau. The wage universe is restricted to reflect the characteristics of H-1B applicants — skilled, college-educated workers employed in the private sector.

For each age between 22 and 65, we discount the ACS cross-sectional mean wages for subsequent ages by either 3 percent or 7 percent, as specified by Executive Order 14192, and sum the discounted values to calculate the expected NPV of earnings. Finally, we divide the NPV of each age’s projected earnings stream by the corresponding mean wage to derive the expected lifetime earnings multiplier.

For workers with age n, discount rate r, and ACS cross-sectional mean wage w, the equation for NPV multiplier is as follows:

We assign the NPV multiplier for 22-year-olds to all age groups younger than 22, and the multiplier for 59-year-olds to all ages above 59. Because H-1B visas require applicants to hold at least a bachelor’s degree, nearly all applicants are 22 or older. The few 20- and 21-year-olds in the sample are likely freshly graduated from college and are therefore treated the same as the 22-year-old recent graduates. Conversely, H-1B awardees are expected to work for two full visa terms (six years), so individuals between 60 and 65 can reasonably be assumed to remain employed for at least six additional years. Since most U.S. workers begin retiring around age 65, ACS cross-sectional mean wages beyond that age are not representative of actual late-career earnings. Given these limitations, the best practice is to apply the same multiplier used for 60- to 65-year-olds to those continuing to work past 65.

Our preferred proposal aims to maximize the total long-run earnings of H-1B awardees. To do so, we multiply each applicant’s wage by the NPV multiplier corresponding to their age and rank the resulting products in descending order to allocate visas under the regular (65,000) and graduate (20,000) caps.

3. Simulating different H1-B selection schemes using synthetic samples

The strict randomness of the current H1-B lottery for the regular lottery cap makes the lottery winners a representative sample of the universe of all workers who entered the lottery.

Using the H-1B lottery winners from each fiscal year, after applying the data cleaning procedures outlined above, we first subset the sample to those who answered “B” in Section 3, Question 1 of Form I-129, indicating selection under the uncapped 65,000 quota. Among these uncapped winners, we then retain only approved petitions to calculate the approval rate. Since the lottery is random, we assume that all entrants faced the same approval probability as the uncapped sample and simulate only those whose applications would have been approved.

Among the uncapped lottery winners whose petitions were approved, we calculate the share of individuals holding master’s, Ph.D., or professional graduate degrees. This share is assumed to represent the proportion of graduate degree holders among all lottery entrants, although it may be underestimated due to missing education data in some I-129 records. With this estimate, we derive the number of H-1B lottery entrants eligible for the graduate cap and those who are not.

Combining the approved graduate degree holders among the uncapped lottery winners with the capped winners (those who answered “M” in Section 3, Question 1 of Form I-129), we obtain a complete sample of graduate degree holders. We then draw randomly with replacement from this group up to the estimated number of graduate-cap entrants. Similarly, we perform random draws with replacement from the non-graduate degree holders among the regular cap’s lottery winners up to the estimated number of bachelor’s-level entrants. Combining the regular cap-eligible and ineligible synthetic H-1B lottery entrants produces a synthetic dataset of all H-1B applicants for a given year who would have been approved had they been selected for a visa.

We generate the synthetic H-1B applicant dataset 500 times and apply the following selection procedures to obtain summary statistics for potential H-1B awardees:

All wage summaries for FY 2021–FY 2023 are adjusted to 2024 dollars.

View the Github with code for replicating this analysis here.

Notes

Skilled Immigration

Related Posts

Will the New Wave of Place-Based Policy Leave Persistently Poor Areas Behind?

EIG Letter: FTC Should Move to Limit Non-Compete Contracts; Congressional Action Still Needed

Noncompete Agreements – Testimony before the Connecticut State Legislature’s Labor and Public Employees Committee