by Connor O’Brien

Key Findings:

- The COVID pandemic did not induce a massive wave of permanent business closures as some feared. In fact, the opposite happened—total business establishments nationwide stood 7 percent above their pre-pandemic levels as of the third quarter of 2021, the latest data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages shows.

- Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of all counties contained more business establishments in Q3 2021 than they did prior to the pandemic. By contrast, only 44 percent of counties had reached a similar milestone five full years after the onset of the Great Recession.

- The South saw substantially faster growth in business establishments (9.4 percent) than the Midwest, Northeast, or West between Q3 2019 and Q3 2021.

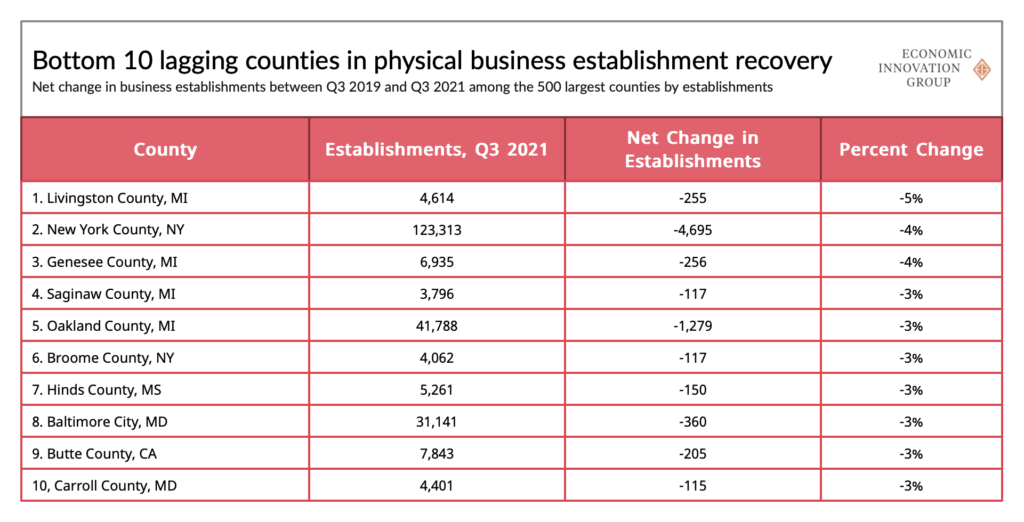

- New York County (Manhattan) lost more business locations (4,695) between the end of 2019 and the third quarter of 2021 than any other county, while Queens, Detroit, and Baltimore also saw outright declines.

- In absolute terms, Los Angeles County (CA), Miami-Dade County (FL), and Maricopa County (AZ) led the country in establishments added, each growing by at least 10,000.

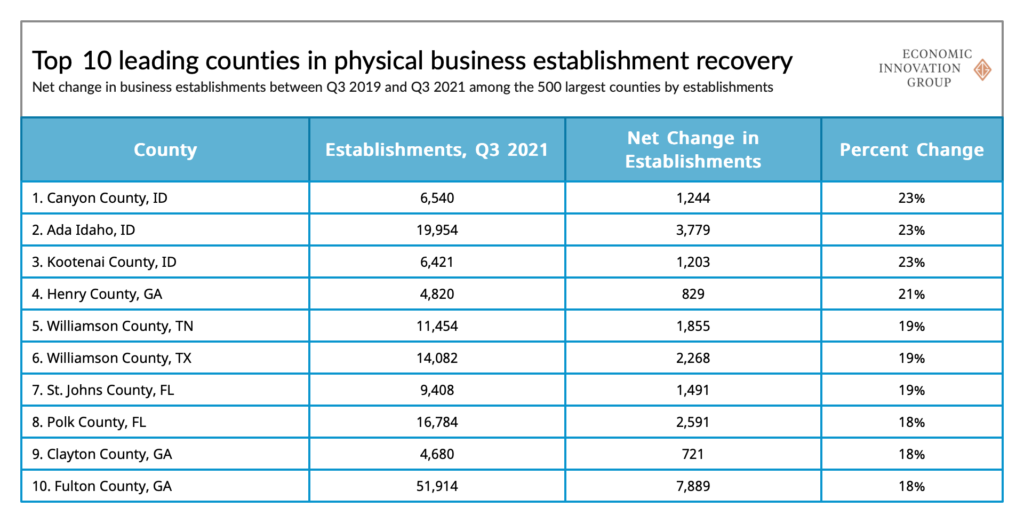

- In relative terms, the biggest gainers were small and mid-sized counties throughout the West and South. Ada County, Idaho, home to the City of Boise, saw its business establishment total grow 23 percent.

- The shock of the pandemic notably disrupted the growth trajectories of certain counties—most prominently, Wayne County, Michigan (Detroit)—while accelerating growth across Sun Belt and Western metros.

- Across all regions, the number of service-producing establishments grew nearly twice as fast as those of goods producers.

- Nationwide, professional and technical services accounted for 23 percent of net establishment growth, adding 169,502 establishments.

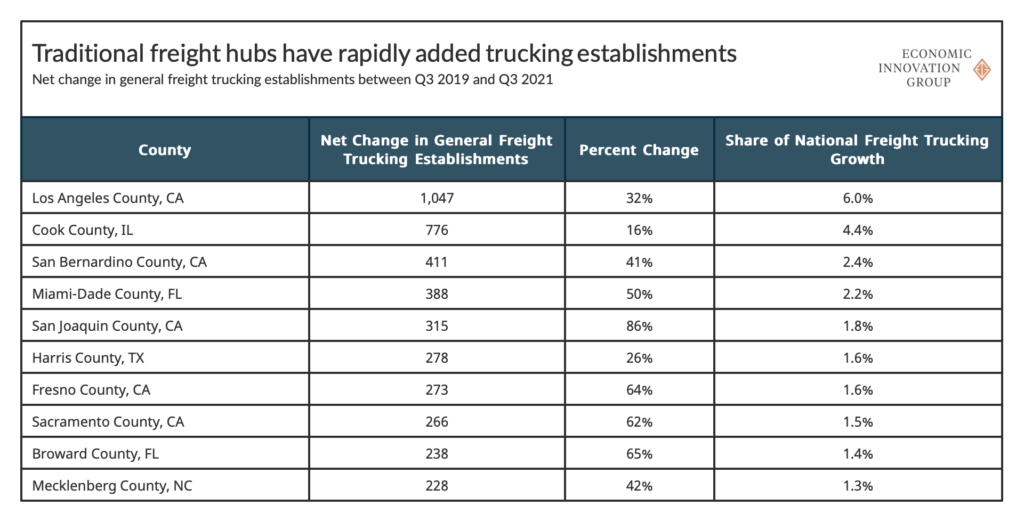

- Reflective of American households’ appetite for consumer durables, freight trucking has grown rapidly, particularly in traditional freight hub counties.

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, fears of a massive wave of small business failures were pervasive. Fortunately, these fears failed to materialize, no doubt due in part to unprecedented direct federal aid to help businesses survive the downturn, combined with household and monetary stimulus that enabled an entirely new crop of enterprises to take root.

Now that we are well into the economic recovery, it’s time to step back and take stock of how the pandemic and its aftermath have altered the trajectory of the economy from an important angle: the physical places of business, or business establishments, that populate American communities. Last month, EIG’s August Benzow highlighted how certain metro areas remain well behind pre-pandemic employment levels, while others saw a swift and complete recovery. What about business growth? Where has the concentration of business establishments grown beyond pre-pandemic levels, and which places appear to be struggling under the weight of closures or changing residential and commuting patterns? New data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages through the third quarter of 2021 sheds light on which sectors and counties have led this recovery, revealing some surprising results.

Nearly three-quarters of all U.S. counties added business establishments through the pandemic and recovery.

Relative to the recovery from the Great Recession, the national rebound from the pandemic’s shock has been both faster and more broad-based. Seventy-four percent of counties had fully recovered to their pre-pandemic concentration of business establishments by Q3 last year. For comparison, a full five years after the peak of the financial crisis in the fall of 2008, only 44 percent of counties had fully recovered. In fact, the share of counties actively shedding business establishments fell over the last two years compared with the prior, pre-pandemic, two-year window.

Business establishments proliferated fastest in the Southeast and inland West.

Between Q3 of 2019 and Q3 2021—the most recent quarter available—the South saw rapid establishment growth (9.4 percent), ahead of the West (7.3 percent), Northeast (6.3 percent), and Midwest (5.2 percent). These patterns are consistent with regional performance across other economic indicators during the pandemic, where economic recoveries took hold faster and more strongly in regions that imposed lighter restrictions on in-person business activities.

Leading counties in terms of total establishments added include Los Angeles (23,399), Maricopa County (13,070), Miami-Dade (13,205) and Orange County, California (8,609). Rounding out this list are largely Sun Belt and interior Western metros like Salt Lake County, Utah, Fulton County, Georgia, Broward County, Florida, and Palm Beach County, Florida. Of the top 25 counties by total business establishments added, only Middlesex County, Massachusetts, including many of Boston’s wealthiest suburbs, lies outside either the South or West.

Beyond metro areas, rural counties in the Southeast and West have, in many cases, fared very well. In Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Florida, most counties added business establishments at rates faster than the country at-large, even those not immediately bordering an urban center. Nevertheless, even in these states, denser counties tended to add business establishments at a higher rate, pointing to the strength of the Southeast’s major metropolitan agglomerations. In Georgia, for example, counties with population densities of at least 1,000 people per square mile experienced a 17 percent increase in establishments, whereas those with fewer than 100 people per square mile grew 10 percent. In the Mountain West states of Colorado, Utah, and Idaho, denser areas grew about four percentage points faster than those with a lower density than the country at-large.

Business establishments have also increased substantially in both metropolitan and rural parts of the Mountain West, one of the country’s fastest-growing regions generally and a popular hotspot for remote workers seeking recreation and open spaces during the pandemic. Ada County, Idaho, home of the City of Boise, is one prominent example. The county added 3,779 business establishments between Q3 2019 and Q3 2021, an increase of 23 percent. The composition of this growth is largely what one would expect for a region serving as a lower-cost magnet for a new class of remote workers. Real estate agent and broker establishments grew 47 percent, computer programming services grew 63 percent, and residential remodeler establishments increased by 58 percent in just two years. Boise has, in fact, become a hub for those leaving California seeking a lower cost of living and recreational amenities, enabled by widespread flexible remote work arrangements. Incredibly, statewide, the number of business establishments in Idaho grew by one-quarter between 2019 and 2021, leagues ahead of any other state.

In other parts of the country, the fastest-growing counties are new suburbs that were already booming before the pandemic. Williamson County, Texas, which encompasses Austin’s northern suburbs and saw 19 percent business establishment growth, is one such county. The 2020 Census estimated the county’s population at over 609,000, up from just over 422,000 in the 2010 Census and slightly less than 250,000 in the 2000 Census. Thus (and intuitively), business establishments are following Americans flocking to lower-density, more affordable suburbs—a trend accelerated by both remote work and high central-city housing costs.

Some large coastal metros and parts of the Great Lakes and Midwest have been slow to rebound.

Meanwhile, net establishment losses were registered in many sparsely populated counties in the Plains, parts of the Mississippi River Basin, the interior Northeast, and particular states such as Michigan. Yet in sheer magnitude, losses were steepest in certain coastal and older cities in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. New York City has outright lost business establishments, as have Baltimore and Detroit (Wayne County, Michigan). The southeast corner of Michigan has been particularly slow to recover, and a number of counties outside Detroit are among the national leaders in business establishments lost since 2019. Businesses in this region were confronted with early Covid case waves significantly higher than national averages, along with some of the strictest stay-at-home measures in the country. Meanwhile, San Francisco has added just under 700 net establishments, amounting to 1 percent growth. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that the mayors of both New York and San Francisco have publicly campaigned for downtown office employees to return to in-person work. Manhattan is still down nearly 400 full-service restaurants, 300 limited-service restaurants, and hundreds of other service establishments compared to Q3 2019. San Francisco is in a similar position, adding a modest number of computer programming (141) and management consulting (135) establishments but losing full-service restaurants, drug stores, dentist offices, and other in-person services.

The pandemic accelerated pre-crisis trends in some counties but dramatically altered the growth trajectory of others.

In many counties, pre-pandemic and post-pandemic trends look similar, or in some cases were modestly accelerated by the Covid shock. However, many other counties experienced dramatic changes in trajectory. Ada County, Idaho, for example, ranked 212th among the 500 largest counties in establishment growth between 2017 and 2019, but shot up to second within this group over the subsequent two years. Cobb and Fulton County, Georgia grew at 2 and 4 percent respectively in the two-year window prior to the pandemic, but each grew more than 15 percent in the next two years. Those counties experiencing the largest “reversal of fortune”—or positive deviations from their prior two-year trend—are heavily concentrated in Idaho, Georgia, North Carolina, and a handful of other states in the West and Sun Belt.

In contrast, negative reversals were widely dispersed but most common in the Midwest. Wayne County, Michigan, experienced the second-largest negative reversal relative to 2017-2019 trends. Total business establishments there grew 16 percent between the third quarters of 2017 and 2019, but shrank 2 percent in the following two years. In fact, of the 500 largest counties, the 12 which saw the largest negative shock relative to trend were in Michigan. Had Wayne County remained on its prior two-year growth trend through 2021, it would have added another 5,400 business establishments. Instead, it shed 770. (At this point, it is worth noting that the QCEW data underlying this analysis is provided by states themselves and aggregated by BLS, which can introduce state-level bias into the data if a state reclassifies certain establishments or adjusts its methodologies in manners that others don’t. We do not believe such bias explains Michigan’s poor performance, given the troubles Michigan businesses have felt during the pandemic, but we would be remiss not to issue the caveat). San Francisco was on pace to add nearly 1,500 new business establishments and instead lost roughly 800. Manhattan added fewer than 650 establishments in the two years prior to the pandemic, but lost a whopping 5,000 during and after.

These changes relative to prior trends defy any one overarching narrative. One cannot safely say, for example, that cities suffered while outer suburbs or rural areas benefited, given the heterogeneity in each category. And though the Sun Belt and interior West did generally fare much better than their coastal counterparts, there were places on the coasts, such as Hudson County, New Jersey, that grew much faster during the pandemic than they did before. Some of this scrambling of regional growth trajectories may prove permanent and others ephemeral. Regardless, the scope and consequences of these changes may take years to sort out.

Growth has been particularly strong in professional services, social assistance, and trucking

Services have led the way in the business establishments recovery thus far, growing 7.9 percent in two years—nearly twice as fast as goods-producing sectors (4.5 percent) in all four regions of the country. The growth of goods-producing businesses has remained steady (4.5 percent between 2017 and 2019) while service growth has doubled from its 4.1 percent rate between 2017 and 2019. This may not be intuitive given the enormous surge in consumer spending has been heavily slanted towards durable goods purchases, creating red-hot markets for automobiles and home appliances; however, “services” in this context includes not just retail and restaurant storefronts (which have seen little to no growth), but also information and technical, professional, and social services in which enterprise growth has been most rapid.

Indeed, establishment-level trends broadly track the shifts in economic activity the pandemic triggered (or in some cases accelerated) across the economy. Professional and technical services accounted for 23 percent of the approximate net 746,000 establishments added between Q3 2019 and Q3 2021. Major industries adding establishments in this sector include computer programming services (28,791); administrative and management consulting services (23,848); and computer design services (16,895). Research and development in biotechnology, nanotechnology, and physical sciences added a combined 9,180 establishments, each growing more than 20 percent.

As the national trend of population aging continued, growth in support services for the elderly and disabled added 99,232 new establishments, accounting for 13 percent of national net establishment growth. Mental health practitioners (6,359 net new establishments), home health care services (5,557), and specialty therapists (4,565) also added establishments or offices more rapidly than the overall economy. The impact of the pandemic on nursing homes may cause a shift to at-home elder care, though it’s too soon to tell if this effect is substantial.

The major sector that shed the most establishments was “other services,” a broad category that includes household services like cooks, gardeners, and home cleaning, along with services like home and car repairs, dry cleaners, and nail and hair salons. This sector lost 16,582 establishments. Other shrinking sectors include wholesale trade brokers (11,460), clothing stores (6,620), electronic appliance stores (1,691), and furniture stores (1,139). Here, the effects of early pandemic restrictions and work-from-home arrangements are most visible, as physical stores closed in favor of their e-commerce competitors (an industry that saw 31 percent growth over the last two years), and households remaining home took on a greater share of home chores like cooking and cleaning.

Surging demand for durable goods and associated freight and delivery services from e-commerce orders is reflected in the 19 percent surge in freight trucking establishments, accounting for 2.3 percent of net national establishment growth. As one might expect given the need for freight services in every corner of the country, growth in this sector has been widely dispersed. Nevertheless, traditional freight transportation hubs with major ports, airports, and interchanges have seen tremendous freight trucking growth, adding establishments much faster than the economy as a whole.

Whether these trends continue, abate, or even reverse will depend on several factors, including the permanence of work-from-home arrangements, supply chain bottlenecks and labor shortages at coastal ports, and Americans’ appetite for durable goods over retail and storefront services. For now, the economic effects of the pandemic and its aftermath continue to substantially alter the landscape of American business growth.