By Kennedy O’Dell and Kenan Fikri

The American Jobs Plan (AJP) is among the most sprawling and expensive legislative packages in recent memory. Organized loosely around the concept of infrastructure, the package includes a suite of policies ranging from investments in bridges and highways to new innovation assets and job training. A survey of the sea of investments and new programs included in the package reveals a continuous thread: conscious investment in the nation’s distressed communities and in economic resilience more broadly. The AJP contains multiple elements that target the nation’s lagging regions, recognizing the power of strategic infrastructure investments to incubate economic activity, broaden market access, and uplift distressed communities. However, combating rising spatial inequality is not as simple as matching investment to distress—capacity matters—and the administration should think bigger about how it can reshape government to deliver better outcomes for American communities.

For this post, we assessed the AJP against the principles we laid out earlier this year in the policy brief “Uplifting America’s Left-Behind Places: A Roadmap for a More Equitable Recovery.” We find its intentions and ideas score well on many fronts, and it conveys an admirable understanding of history and local context. rethinking how the federal government delivers such programming and what innovative financing tools it brings to bear may further enhance the AJP’s impact.

- The plan includes a number of ideas that target geographic inequality head-on. The AJP includes a plethora of place-based programs that try to operationalize some of the latest thinking in economic and community development. Together, they signal a real commitment from the Biden administration to boost the fortunes of distressed or otherwise “left-behind” places and their residents.

-

- The Rural Partnership Program provides $5 billion for local planning and capacity building in rural and tribal areas and represents a major, meaningful investment. Limited local capacity is a serious hurdle for many small and struggling communities that keeps them trapped in economic distress. It often prevents them from successfully winning federal grants awarded on a competitive basis, for example, and this program seeks to directly address that roadblock.

- The Regional Innovation Hubs proposal mirrors the vision of the Endless Frontier Act to foster more innovation across a broader swath of the country. It would entail considerable federal market-making investments into key future technology clusters in mid-sized metro areas. The emphasis on new business starts, inclusive workforce development, and urban-rural linkages is also welcome.

- The proposed Community Revitalization Fund dovetails with the lessons learned from watching the Opportunity Zone (OZ) incentive closely: the most meaningful community development projects often require additional flexible public support that can be used for anything from planning and technical assistance to closing funding gaps to get a project off the ground.

- Multiple parts of the AJP focus on cleanups and environmental remediation in distressed communities, which are home to far more than their fair share of the country’s brownfield sites. These are not just health hazards, but they are also major obstacles to redevelopment and bringing economic activity back to these communities. A focus on them—not to mention lead remediation, ensuring adequate sewage systems, and attending to other foundational aspects of development and well-being—is appropriate and overdue.

- Programs aimed at helping workers and communities navigate economic change should be particularly beneficial for struggling regions.Many of the country’s distressed communities are in the positions they are today because they struggled to navigate economic change of one form or another. Key elements of the AJP—such as funding a national buildout of broadband, supporting dislocated workers, and investing in the entrepreneurial ecosystems—are designed to help lagging places and workers catch up to the knowledge-centric economy of today and smooth the transition to a cleaner industrial future in the years ahead. These investments to facilitate adaptation and economic resilience should disproportionately benefit lagging communities, if well-crafted, well-targeted, and well-executed.

Expanding broadband access is critical to ensuring all Americans have the chance to participate in the 21st century economy. The pandemic underscored the urgency of connecting as many Americans as possible to the best connections possible through vehicles that are innovative, sustainable, and affordable to build and use. The AJP’s broadband agenda is guided by several positive principles—not just building it, but also ensuring competition in the sector, transparency in pricing, and practical affordability for households—but how these principles are operationalized in terms of build out details and price tag will shape how successful the effort is. In its final form, the package should make space for a range of solution sets and technologies, opting for a “yes, and” approach that embraces the potential of both public and private investment to build-out a flexible and affordable network that reaches every American. For now, the AJP seems to recognize that investing in pervasive, high-quality broadband is a downpayment on spatially equitable growth in the future.

Programs to help workers and communities navigate economic change, such as the proposed $40 billion Dislocated Workers Program and sector-based training initiatives, should help smooth transitions from the old economy to the new one. Targeted assistance to help workers adapt will especially benefit communities with a strong legacy industry presence and those that will be on the frontlines of a transition to a clean economy. While the AJP includes a significant investment in workforce development, the devil will be in the details. Workforce development in general is a realm of public policy in which it is hard to define and measure success, and standing up an effective new national program that efficiently targets those most in need will be challenging. Some programs like the Appalachian Regional Commission’s POWER program have been targeted and relatively successful while others, such as Trade Adjustment Assistance, have been small bore relative to the challenges they were established to address. The United States spends very little relative to other advanced countries, and even then the consensus is that the country does not spend its resources particularly well. Fresh thinking is much needed on this front—and follow-through, too.

In addition, the proposal includes a commitment to building entrepreneurial ecosystems throughout the country to seed the employers and innovators of tomorrow. The proposal includes $31 billion in funding aimed at increasing small business access to credit, capital, and R&D funds. It also includes funding for community-based small business incubators and innovation hubs to support the growth of entrepreneurship in minority and underserved communities. American entrepreneurship never recovered from the Great Recession, to the detriment of communities and workers. Investments into softer ecosystem infrastructure may help ensure the recovery from the pandemic recession is much more home-grown.

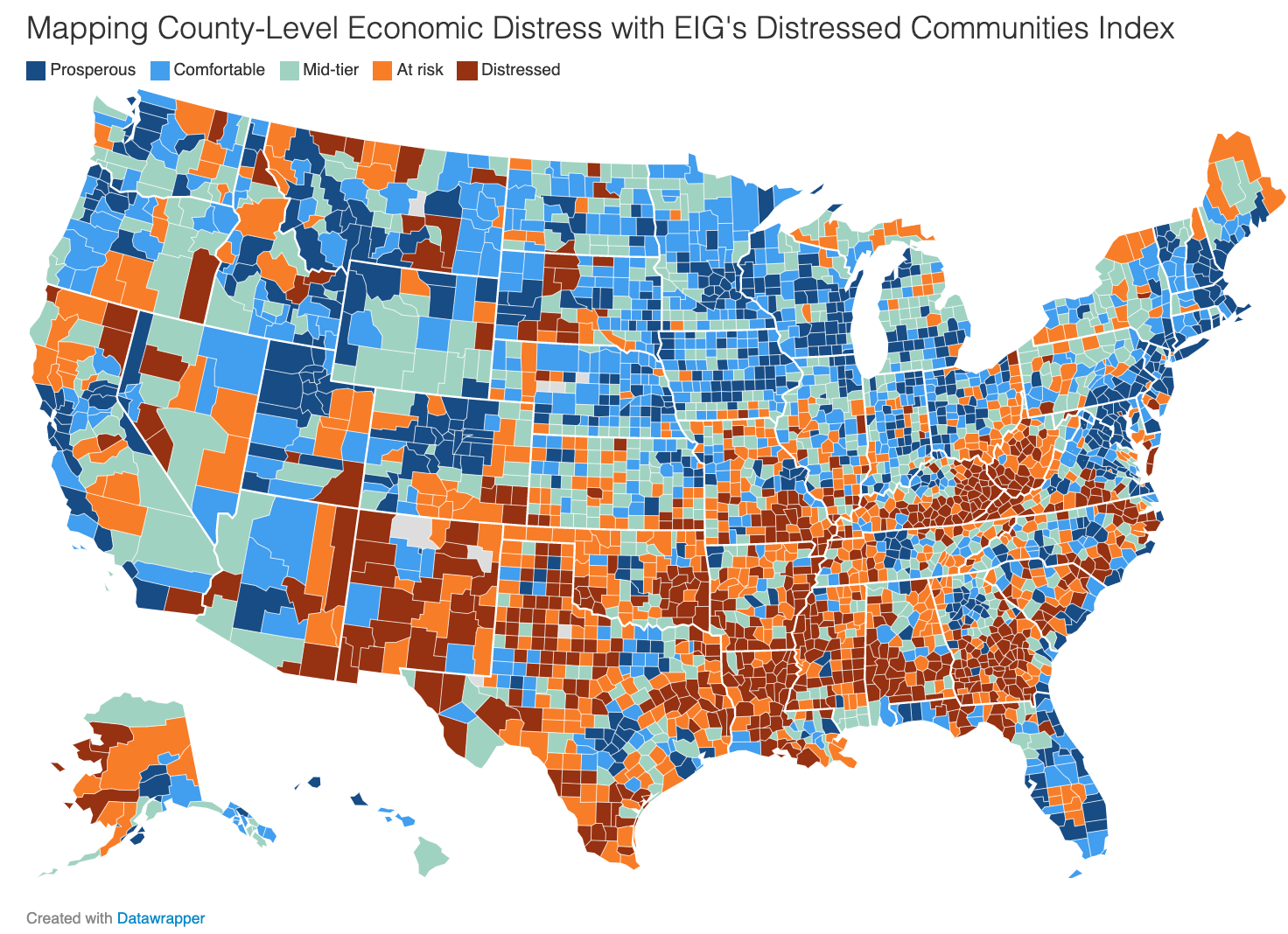

- Definitions of “distress” matter.The AJP is a consciously place-based proposal, and it makes clear the administration’s intent to target struggling, marginalized, and generally underserved areas. The sentiment behind the targeting expressed in the bill is quite positive and represents the increasing geographic awareness at the highest levels of federal economic policymaking. Nevertheless, good intentions must be transformed into precise policy. For now, the AJP punts the critically important question of how the terms distressed, disadvantaged, or underserved are operationalized to Congress. How these broad categories are defined will have serious implications for the reach and prospective impact of a program. Actual interventions must be carefully and intentionally targeted, with an eye to the strengths and weaknesses of using a particular metric, like the poverty or unemployment rate, or a particular scale, such as commuting zones or census tracts, to try to solve the issue at heart with the tool at hand.

- Acknowledging the errors of the past while making space to dream bolder moving forward is one of the strengths of the bill.Too often, policymakers move forward on new programs without reckoning with the lingering impacts of previous interventions. The AJP works hard to avoid this mistake and acknowledge the degree to which past histories of federal interventions live on in community outcomes today. The $20 billion investment in reconnecting urban neighborhoods severed from their broader communities by highway construction decades ago is one concrete example of this historical awareness in action. The plan’s commitment to ensuring future investments advance equity, affordability, and opportunity builds on these lessons.The proposal also makes space for big, potentially transformative projects, as evidenced by a fund for regional or national projects with significant economic impact “too large or complex for existing funding programs,” without giving specifics. It also includes some innovative solutions to entrenched issues, such as encouraging zoning reform through a new competitive grant program that would award flexible and attractive funding to jurisdictions that take concrete steps to eliminate restrictive zoning. However, zoning reform is one of many ideas in the plan that may be left on the cutting room floor in Congress, as the plan encounters pushback on its expansive definition of infrastructure.

What’s Missing?

While the AJP impresses as a collection of programs and commitments, it falls short on rethinking the institutions in charge of delivering them. The plan would benefit from the creation of a centralizing agency or entity within the Executive Branch that could unite funding streams with a clear vision and back them with strategic direction. More institutional and programmatic experimentation around infrastructure, climate, and development financing, not just spending, would also strengthen the plan.

Ensuring the AJP reaches its full potential requires more than money and intent—it requires coordination and strategic direction.

While the plan contains a number of promising individual policies and programs, it does not seem to include the administrative infrastructure necessary to ensure they add up to more than the sum of their parts. A national effort to marshall resources on this scale should be met with strategic direction and, at a minimum, deep cross-agency coordination. Better yet, a cabinet-level office (an enhanced and empowered Economic Development Administration is a possibility) dedicated to advancing equitable economic development would go further to put accountability behind the plan’s ambitions to not just distribute federal largesse, but truly incubate development in distressed and marginalized parts of the country. EIG called for such an agency earlier this year, and the AJP is just the sort of bold legislation that opens a window for meaningful institutional reform at the federal level.

The difficulty in estimating the ultimate geographic impacts of the proposal is, in and of itself, a strong demonstration of the need case for a dedicated federal entity to put the pieces together. A division of the federal government should be broadly considering the answer to the same type of question everyday Americans ask about the bills Congress considers: How will this bill in its entirety affect my community, be it Akron or Boise or Chattanooga? The infrastructure plan includes a number of important legislative quivers, but without the coordination and long-term accountability that a coordinating entity provides, their success may be limited.

The plan does not push far enough on costs and process improvements in infrastructure delivery.

Infrastructure projects in the United States are incredibly expensive and are often completed over an unduly long time period. Reducing cost and red tape on a systematic level is key to ensuring that infrastructure investments can actually reach left behind places and people. A recent Brookings report included several suggestions for potential process improvements, including experimenting with fast-tracking project reviews to reduce long-term costs and exploring the potential benefits of supporting state and local predevelopment activities to accelerate project delivery and improve outcomes. Policymakers might also consider requiring final cost reporting to help control costs and improve the government’s ability to assess the efficiency of various projects. The government should also carefully consider the regulatory process for infrastructure projects more broadly. Good norms and regulations help ensure a project fits community needs and environmental standards. Overly onerous regulations stall good projects and run up costs, further taxing local or regional budgets in general and posing a difficult challenge for already financially overburdened distressed communities in particular.

The Biden plan appreciates that improvements to process are key—it includes several calls for local capacity building, an essential building block for successful projects. Streamlining the process for infrastructure projects broadly is a complement to capacity building. In general, policymakers should strive to make the process simpler, smarter, and more efficient.

More innovations in development finance are needed to seed sustainable change.

While the AJP opens the spigot on federal infrastructure spending for a long-parched nation, it contains few specifics about novel financing mechanisms to unlock private capital to come in alongside and at scale. The plan may have missed an opportunity to stand up something like an infrastructure bank (the UK just announced one), a green bank, or a national development corporation that could become a sustainable fixture of our infrastructure and development landscape.

Innovative financing tools are essential to plugging the public resource and private sector capital access gaps that stymie economic development in struggling corners of the country, from disinvested urban neighborhoods to underdeveloped rural regions. In our recent brief, we called for a domestic development finance corporation designed to provide the sort of financing private markets will not, such as loan guarantees, direct equity contributions, and securitization across high-risk entrepreneurs or locations. Such financing would help fill the space between existing federal grants, loans, and programs to incubate market activity in some of the country’s weakest-market areas. The same basic concept can be extended to financing a clean transition. It is easy to see how a large infrastructure finance arm investing in projects of national (and local) significance—which the plan alludes to—would find a home in such a new institution as well. The full development corporation or bank would find a logical home within the new federal development agency mentioned just above.

In addition, the AJP could more intentionally build on promising new investment models sprouting through the bipartisan Opportunity Zones program. Public private partnerships are now using OZ financing to build out rural broadband in Maine. OZ financing is helping convert one of the country’s most notorious brownfield sites into a new logistics center in East Chicago. OZ capital is financing urban agriculture and vertical farming in legacy cities, biofuels in the Southeast, water technology startups in Appalachia. And it is fostering density and in-fill development in cities across the country. The pending infrastructure package provides a prime chance to experiment with regulatory flexibility to allow for OZs to more easily deliver private capital in service of meeting the country’s infrastructure and climate goals.

Conclusion

The AJP stands out as one of the most substantial—and substantive—efforts to tackle the country’s widening geographic disparities to come out of the federal government in a long time. If passed, it could meaningfully impact the trajectories of communities throughout the country, especially those struggling under the weight of environmental injustices and those most exposed to the downsides of economic change. Yet individual programs will have the greatest impact when executed as part of a well-coordinated, strategic plan. Congress and the Biden Administration should seize the moment to build something larger than an assemblage of disparate initiatives and consider complementary institutional reforms, up to and including a cabinet-level agency in charge of economic development outfitted with a best-in-class development finance arm. The AJP provides a new vision for infrastructure investment, but its successful implementation may depend on the establishment of a new system that can carry out its commitments in full consideration of the tight relationships among people, place, and economic growth.

For more place-based policy discussion, see EIG’s recently released spatial inequality policy brief.