Uplifting America’s Left Behind Places: A Roadmap for a More Equitable Economy

By Kenan Fikri, Daniel Newman, and Kennedy O’Dell

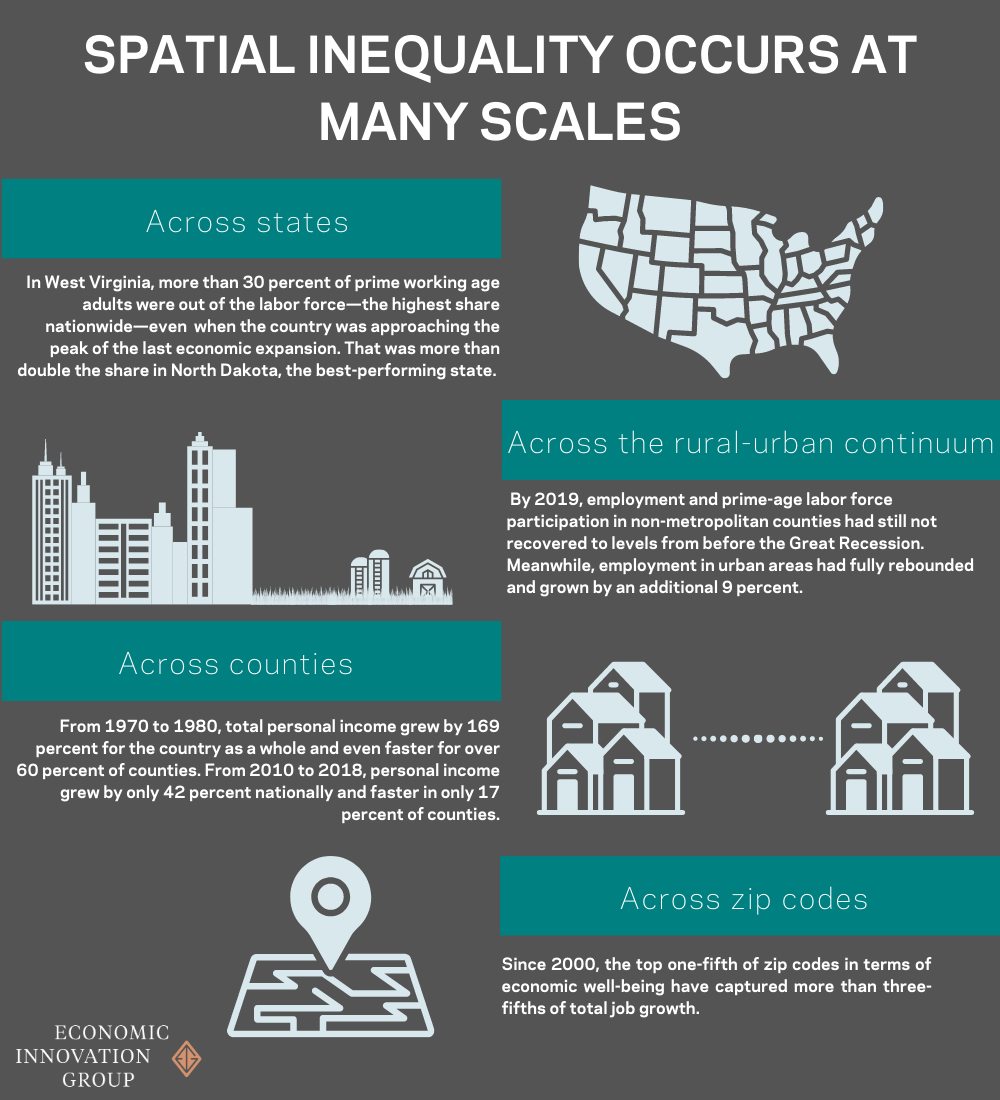

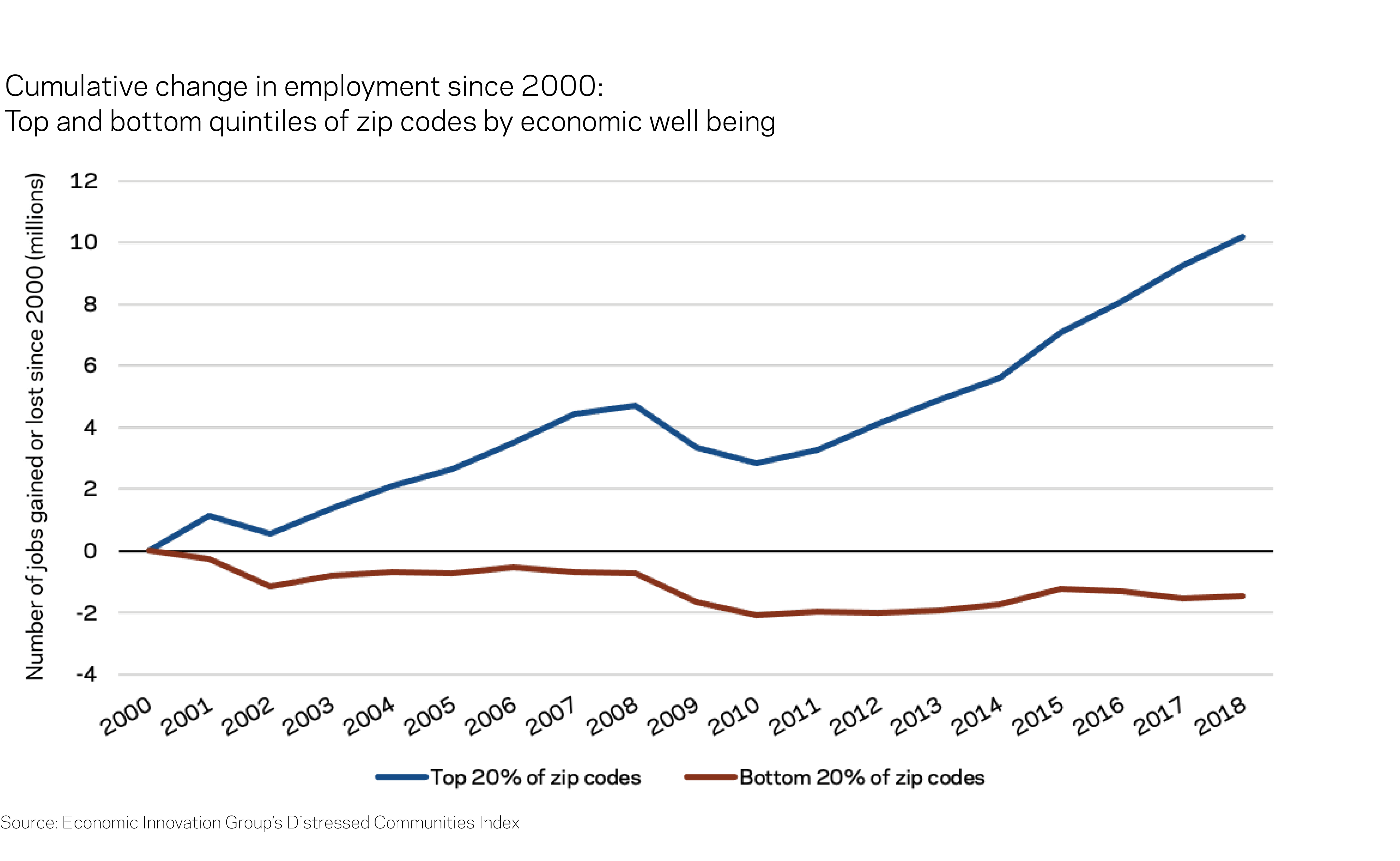

The Issue: Spatial inequality

Spatial inequality, or geographic unevenness in economic well-being, is on the rise. Rather than shrink over time, spatial inequalities have become a defining feature of the American experience in recent decades and were accelerating in the run up to the COVID-19 pandemic. When communities undershoot their economic potential, the entire country’s progress is held back. With economic disruptions of historical magnitudes occurring now and on the horizon—the climate crisis first and foremost—the entire federal stance towards geographic inequality requires a pivot from redressing damage after the fact to mitigating it at the outset by investing proactively and positioning localities to thrive. A new administration and a new Congress now have a chance to recalibrate the federal approach to economic development to empower more people in more places to participate in the country’s advance.

Spatial inequality is related to racial inequality.

Minorities are especially disadvantaged by deep spatial inequities, and the pandemic has served as a painful reminder that economic, racial, and health inequalities all converge spatially. Blacks and Native Americans are three-times more likely to live in a distressed community than whites, the product of decades of discrimination and segregation.

There’s nothing inevitable about the degree of spatial inequality in the United States and policymakers have failed to deliver solutions to meaningfully address it.

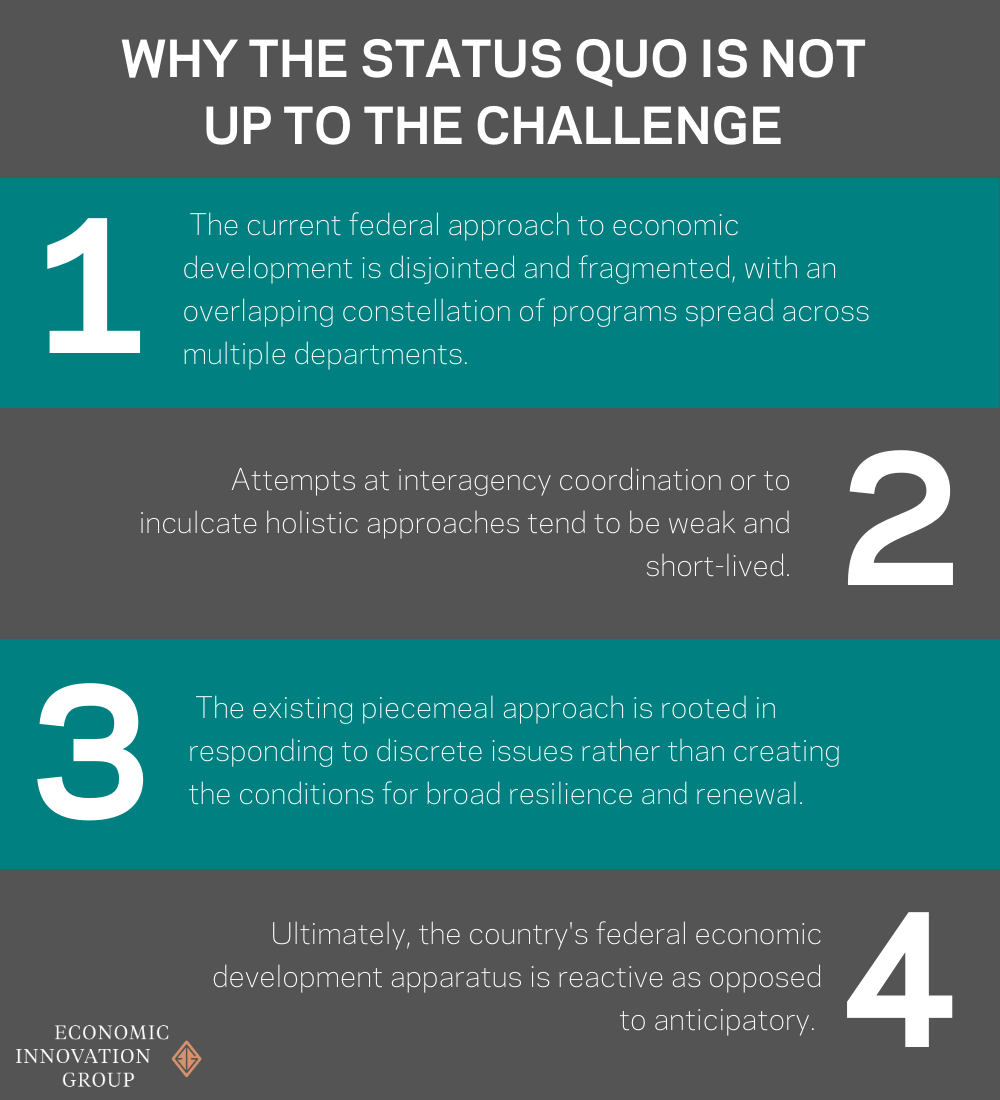

Some gaps between places are natural, but the scale of the disparities, speed of the collapse in some places, and longevity of distress in others are phenomena that have been exacerbated by policy myopia and neglect. Decision-makers have broadly overlooked the geographic ramifications of trade, competition, and deregulation policies.5 Prevailing economic models have blithely assumed that local economic transitions could proceed seamlessly. As a result, domestic economic development has been underfunded, its work an afterthought. The established toolkit has largely failed to help large swathes of the country successfully navigate technological disruptions and economic change. It has also failed to incubate growth in deeply distressed areas over decades.

The United States must learn from the past 20 years of economic disruptions—from the China trade shock to digitalization and the pandemic—to fortify local economies to better withstand whatever lies ahead. Achieving the Biden administration’s climate goals, for example, will require disruption, perhaps on an unprecedented scale. The nation cannot afford to confront that transition with the same hands-off approach of the recent past that had the federal government largely stand by as the country’s manufacturing belt hollowed out, for example. The federal policy stance vis-à-vis regional economic transitions must shift from too little, too late (e.g., Trade Adjustment Assistance) to a more proactive, anticipatory stance that helps communities adapt before they decline and find opportunity in economic change.

The Solution: Reorient government to forge more inclusive economic growth

If the Biden administration and its partners in Congress hope to use this moment to build back better, they must place spatial inequality at the heart of their domestic policy agenda and institutionalize new approaches to economic and community development across the government. Place-conscious policymaking requires a whole-of-government framework for advancing regional inclusion and adapting the structure of government to reflect the prioritization of inclusive growth.

Filter ideas through a spatial lens

We encourage executive branch policymakers to routinely apply geographic filters at two stages of the policy process: incubation, in the National Economic Council and Domestic Policy Council, and review, in the Office of Management and Budget, particularly the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Committees and lawmakers in the legislative branch can adopt parallel initiatives.

Place-conscious policymaking is about more than the place-based policies themselves, it is about instilling spatial awareness into everything relevant the federal government does. Situating a geographic lens at the center of the policy process is important because competition policy, trade policy, immigration policy, and even highway spending all have unintended geographic ramifications that are better anticipated ahead of time rather than dealt with after the fact.

A whole-of-government approach to economic development

| Meet demand |

|---|

| Federal spending provides ample evidence that demand for federal economic development services far outstrips the normal supply of funding. Congress relies on the Economic Development Administration as a vitally important transmission channel for delivering emergency funds when disaster strikes. Better yet would be a more strategic federal approach to fortify local economies beforehand, too. |

| Rise to the challenge and lead |

|---|

| In an ideal world, a new, independent, cabinet-level entity with the express mission of driving domestic economic development and regional economic resilience would consolidate related activities from existing agencies under a single organizational roof.6

Regardless of the exact form it takes, communities nationwide would benefit from an elevated, empowered, centralized entity to drive federal economic development policy. An empowered entity must provide coherence, leadership, vision, and final accountability for economic development policies across the bureaucracy. |

| Innovate |

|---|

| Federal policymakers should expand the range of tools in the economic development finance toolkit in order to nurture private sector activity to the country’s persistently lagging regions and communities. A Domestic Development Finance Corporation would provide the sort of financing private markets will not—loan guarantees, direct equity contributions, and securitization across high-risk entrepreneurs or locations—that allow private commerce to take hold and flourish. |

Several near-term, actionable priorities would help lay the groundwork for such ambitious institutional reform:

- Undertake a thorough review of the efficacy and efficiency of all existing economic development programs and provide recommendations to Congress as to whether the program is best administered by its current agency or should be consolidated under the expanded purview of another one.

- Establish permanent interagency task forces co-chaired with the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Agriculture to coordinate economic development efforts across programs and agencies.

- Set clear goals, in coordination with the White House and Congress, to guide the country’s domestic economic development agenda.

- Work with partners in Congress to create or expand programs derived from best practices to invest in local capacity-building at scale. Local conditions such as fiscal health, administrative capacity, the quality of local leadership, and the depth of staff expertise mediate the success of federal economic development interventions.

- Experiment with a more regional approach to development by adjusting the purview and focus of existing regional development offices or forming a nation-wide network of fully-funded regional commissions and authorities.

The Toolkit: Policies to Address Spatial Inequality

Click through to explore the Policy Toolkit

Conclusion

As it gets to work, the new administration and Congress should direct energy and programming towards chronically distressed places that have suffered from inattention and underinvestment for too long. They should also set out to bolster resilience to a range of economic disruptions—from pandemics to climate change and long-term industrial change—in all communities. An empowered federal agency coordinating economic development policy and an aggressive place-conscious policy agenda are essential to achieving these goals. The legacy of such bold action will be an expanded map of American economic dynamism and prosperity.