By: Kenan Fikri

Americans are losing their jobs. Production lines are halting. Main Streets are shuttering in real time. Washington is preparing to take bold action to save the economy from the fallout of COVID-19. Inevitably, today’s legislative response will carry some unintended consequences tomorrow. For evidence look no further than the Great Recession and its aftermath on entrepreneurship. That era offers crucial lessons in anticipating second order effects that policymakers must internalize—quickly—as they act to save the U.S. economy once again.

In one way in particular, the 2009 financial crisis was a dry run for the current moment: Its repercussions on entrepreneurs and small businesses—the very entities on the front lines of the economic crisis now being wrought by COVID-19—were deep and long-lasting. Untangling causality is difficult in a system as complex as the U.S. economy, but three facts clearly demonstrate how the economy that went into the crisis differed starkly from the economy that came out of it and was far less hospitable to entrepreneurs, the dynamic lifeblood of a healthy economy.

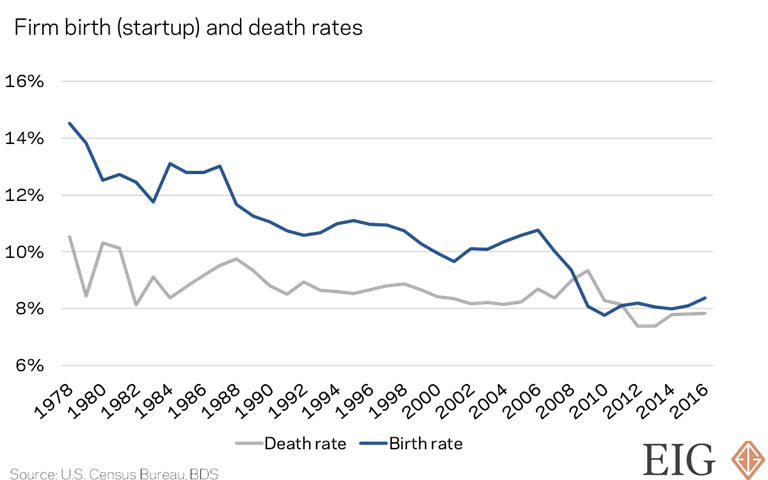

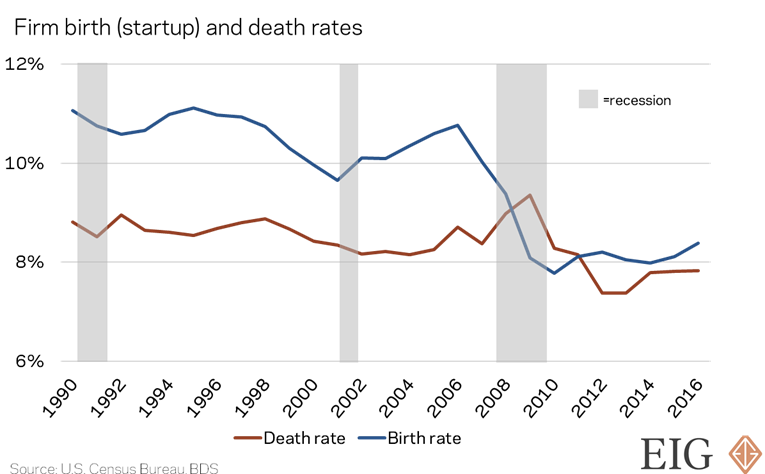

Fact 1: The startup rate never recovered from the Great Recession

The rate at which new firms form in the U.S. economy fell by one-fifth between 2007 and 2009. What is more surprising is that the startup rate never recovered from there. This translated into a missing 100,000 new firms entering the U.S. economy every single year this decade. The evidence suggests the collapse in startup rates wasn’t the product of some long-term secular decline, but rather a direct result of the economic crisis. Something about markets changed in the throes of the crisis that made it harder to start and sustain a new business in the United States than it used to be.

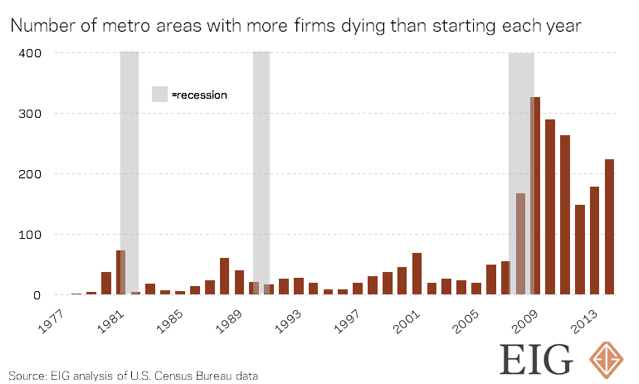

Reducing the startup pipeline to a trickle had real impacts in American communities. Even in downturns prior to the Great Recession, no more than about one-fifth of U.S. metro areas saw more firms shut their doors than hang a shingle in any given year. That all changed in 2009. With startup rates now settled barely above the rate of firm closures, most metro areas see more firms fail than launch each year.

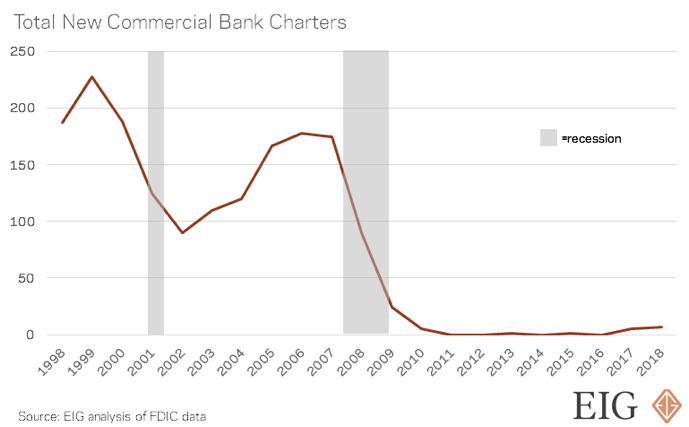

Fact 2: New bank formations never recovered from the Great Recession

More than 1,500 new banks were chartered in the decade prior to the Great Recession. Between 2011 and 2018, only 14 were. Even in a low interest rate environment, this shockingly low number can only be seen as a partial side effect of the measures put in place to stabilize the financial sector in the wake of the crisis. While some financial technology innovations have helped expand access to capital over the past few years, crisis-era regulations strained small banks, drove consolidation across the sector, and essentially removed entrepreneurship entirely from the country’s banking system. The absence of new banks is especially disadvantageous for would-be entrepreneurs and other groups including small and minority business owners traditionally under-served by more conservative established financial players.

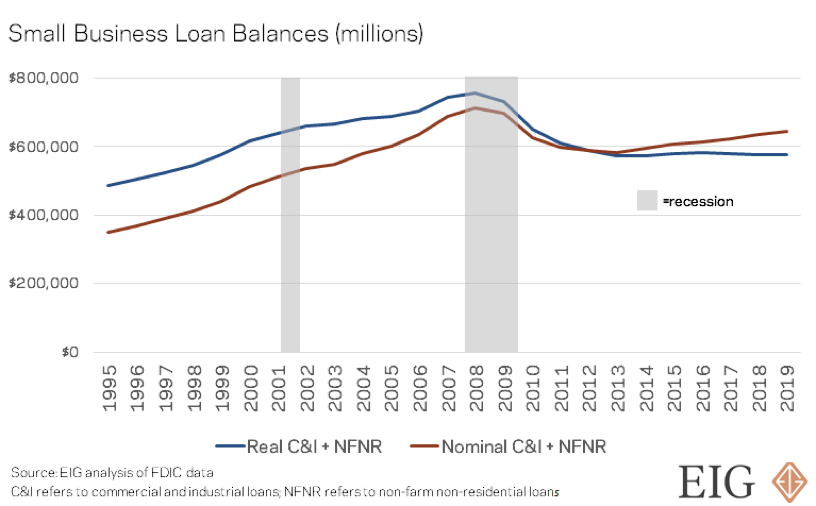

Fact 3: Small business lending never recovered from the Great Recession

Total small business lending (defined as commercial loans under $1 million) fell by nearly one-quarter in real terms during the Great Recession and stagnated thereafter, even as big businesses drove real total commercial lending to new heights. The small loan share fell from 40 percent of all commercial lending in 1995 to 20 percent in 2018. Banking sector consolidation meant that many regional and community banks disappeared or were absorbed into larger enterprises, severing long-established ties between business owners and their trusted bankers. Less lending by established players, fewer new companies demanding capital, and fewer new banks offering it all conspired to produce this dramatic fall and reflect how capital markets grew less accommodating of the needs of new and small businesses in the wake of the Great Recession.

Lessons learned

Entrepreneurs were an afterthought in the policy triage to save the economy and the financial system in 2009. It is imperative not to repeat the same mistake twice. The circumstances are very different, to be sure. The Great Recession was precipitated by a financial crisis, and the policy response to it more completely transformed the financial sector than anything now under consideration in response to the current public health crisis. Promisingly, numerous ideas are circulating to protect small businesses. EIG has advanced its own blueprint to put entrepreneurs at the center of the rescue effort: a Main Street Rescue and Resiliency Program that would offer lending on favorable terms to viable but vulnerable new and small businesses to see them through the crisis. Such proposals are necessary for the moment but will likely only be the first step in healing the economy after the pandemic.

Accordingly, there is one final lesson policymakers can learn from the recent past: responding to a massive economic shock is a dynamic exercise that requires ongoing cooperation and an iterative approach. The legislative gridlock that set in after 2010 prevented any policy recalibrations from taking effect even as the need for further reform became clear. Whatever gets passed this week marks only the beginning. The imperative today is to preserve solid, successful businesses, even as our economic needs evolve over the coming months. Congress, like the rest of us, is in for a long slog. Entrepreneurs and small businesses must remain front and center throughout if the economy that emerges from this crisis is to be more dynamic and opportunity-rich than the one that went into it.