Watch the Full Testimony

By: John W. Lettieri, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)

Introduction[1]

Chairman Kim, Ranking Member Hern, and members of the Committee: Thank you for inviting me to testify regarding how the Opportunity Zones tax benefit can be used to support new and growing businesses in struggling communities.

My name is John Lettieri and I am the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a bipartisan research and advocacy organization focused on the decline of economic dynamism and the growing divides between thriving and struggling American communities.

EIG was a leading proponent of the concept behind Opportunity Zones, and I believe the policy as enacted can provide a new lifeline of much-needed investment to struggling communities nationwide if implemented properly. While the incentive was designed to support a wide variety of needs across communities – from housing, to clean energy, to commercial development – its central purpose[2] was to support new businesses and existing small and medium-sized firms in need of growth capital. My testimony today will focus on the policy, regulatory, and practical steps still necessary to achieving this goal.

The Structure and Goals of Opportunity Zones

While there have been a number of previous federal incentive programs aimed at boosting economic activity in underserved areas, the Opportunity Zones incentive is a sharp departure from past precedent in its scope, flexibility, and structure. Perhaps for this reason, it has generated enormous interest among local leaders, investors, philanthropic organizations, and economic development practitioners. Unlike most other federal programs, this incentive can be used in a variety of ways, making it a potentially important and creative tool for financing a range of economic priorities across many different types of communities. At its core, the policy is intended to support the creation of new economic value within communities, either by establishing something new, such as an operating business or commercial development, or by making large-scale improvements to existing businesses or assets within a community.

The Opportunity Zones incentive provides a series of benefits to taxpayers that reinvest their capital gains into qualifying investments in designated low-income communities. The incentive is designed to reward patient capital, with the most significant benefit kicking in only after 10 years. The communities themselves were selected by governors in each state based upon federal income and poverty criteria. Governors were allowed to designate up to 25 percent of the eligible census tracts as Opportunity Zones, which in turn makes certain investments in those areas eligible for a federal tax benefit. To be eligible, an investment must be made using equity capital and deployed through a “Qualified Opportunity Fund,” which is any investment vehicle specifically organized to make qualifying investments in Opportunity Zones communities per the statute.

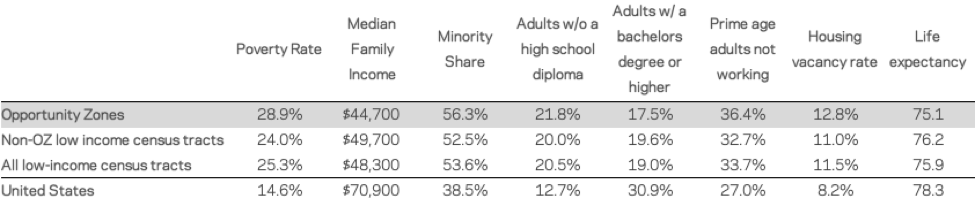

As a group, the designated communities have far higher levels of socioeconomic need than required by statute. They are also needier in terms of poverty rates, median family incomes, educational attainment, and a host of other criteria than the cohort of eligible tracts governors did not select. While the need-targeting was in general strong, a small percentage of designations have drawn justifiable criticism for being undeserving of Opportunity Zone status, despite being technically eligible according to U.S. Department of the Treasury standards. Such concerns should inform future legislative efforts to expand or improve the policy.

How the average Opportunity Zone census tract compares to other peer groups

Source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS) Data, 2013-2017

The State of American Entrepreneurship

Before going any further, I want to briefly examine the state of American entrepreneurship and how it relates to the Opportunity Zones initiative.

Policymakers generally devote too much attention to small businesses and not nearly enough to new businesses. One often hears that small businesses are the backbone of U.S. job creation, but it is specifically the small cohort of new businesses that grow and add employees to which most net new job creation can be attributed each year. EIG’s research finds that new business formation was abysmal in the wake of the Great Recession, both in terms of the rate and scale of new firms, as well as the geographic distribution of net firm formation. Yet this decline in entrepreneurship started long ago and is the centerpiece of an economy-wide decline in dynamism that defies popular notions of the current era being one of unprecedented economic change and disruption.

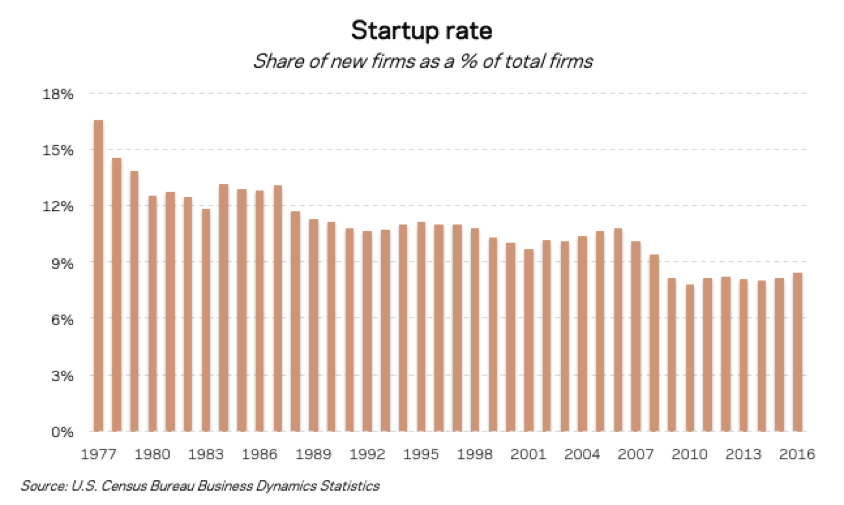

Over the past several decades, the startup rate, defined as the percent of all firms in the economy that started in the past year, has declined across virtually all regions and sectors of the economy. It fell steadily through the 1980s and 1990s before collapsing with the Great Recession. Troublingly, the national economic recovery has done little to improve the rate of business formation. Startup activity finally picked up in 2016, as the rate of new business creation improved to 8.4 percent. Yet even that post-recession high left the startup rate 2 percentage points below its long-run average, which translates to roughly 100,000 “missing” new companies annually.

The latest business application data from the Census Bureau tell us that as recently as the 2nd quarter of 2019, there were 17 percent fewer promising new businesses in the queue than in 2006.[3] The latest figures on actual startups show no real rebound at all between 2010 and 2016, making entrepreneurship one of the few indicators that have failed to meaningfully improve in spite of an ongoing economic expansion. Consider that between 2006 and 2019 real U.S. GDP grew by nearly $4 trillion and our population increased by nearly 30 million, and it becomes clear that the U.S. economy is growing relatively less entrepreneurial every year.

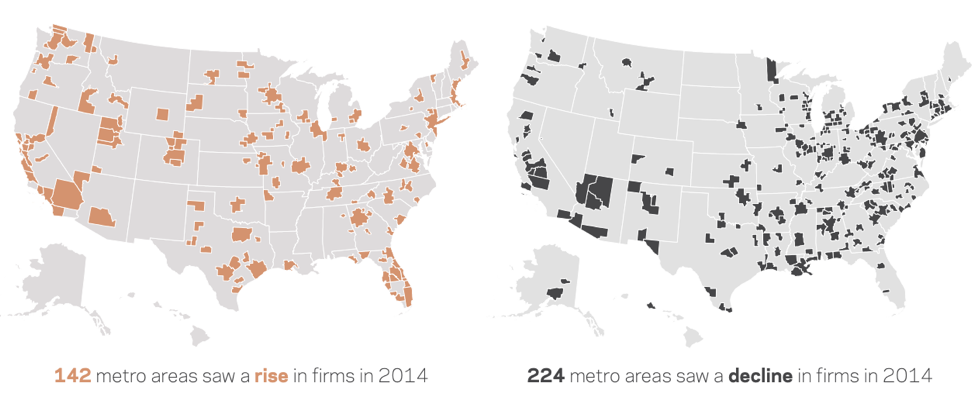

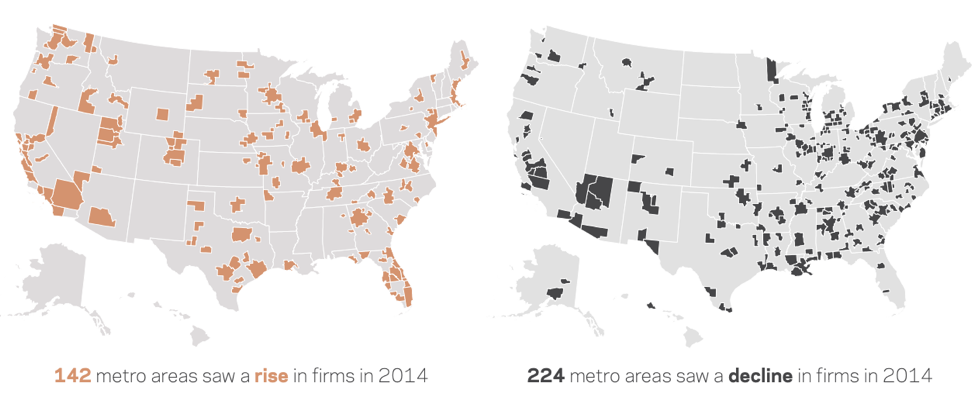

The decline in business dynamism has significant implications for the health of regions and communities. For the three decades prior to 2007, the vast majority of U.S. metro areas saw net increases in local firms each year. This changed dramatically with the Great Recession. Metro-level data from the latest year available, 2014, revealed that 61 percent of U.S. metro areas lost firms that year, meaning too few startups were launched to replace businesses that closed. The trend shows that across much of the country the cycles of churn and creative destruction that keep the economy healthy are breaking down.

Metro areas with increasing (left) and decreasing (right) numbers of firms in 2014

Source: EIG’s “Dynamism in Retreat” and U.S. Census Bureau Business Dynamics Statistics

The slowdown in entrepreneurial activity is even more pronounced in economically struggling communities. EIG’s Distressed Communities Index finds that the typical distressed zip code lost 5 percent of its business establishments from 2012 to 2016. On current trendlines, the same group of zip codes, representing one-fifth of all zip codes in the United States, will never recover the 1.3 million jobs they lost to the Great Recession. While numerous overlapping and complicated forces contribute to these outcomes, it is no coincidence that more entrepreneurial eras in American history were also times of more broadly shared prosperity.

Demographics stand out as a growing headwind for the U.S. economy with significant implications for the future of American entrepreneurship. The United States once enjoyed some of the highest rates of population growth in the developed world. Today, the rate of U.S. population growth stands at its lowest level since the Great Depression and half the level of the early 1990s. Economists have made considerable advances in the past two years explaining how this new development will impact the dynamism of the U.S. economy.

We reviewed the literature on demography and dynamism in a recent report.[4] Two prominent studies demonstrate how the slowing growth and aging of the population leads to fewer new firm starts.[5] An analysis of Moody’s Analytics data found that a 1 percentage point decline in population growth from 2007 to 2017 caused a county’s startup rate to decline by 2-3 percentage points.[6] Another shows how the aging of the large baby boom generation may be contributing to multiple related phenomena: fewer firm starts, an aging firm distribution, a growing concentration of employment into larger firms, and a falling share of national income going to workers.[7] Demographic stagnation and population loss are especially serious concerns for a large share of Opportunity Zones communities, 45 percent of which have lost population over the past decade.[8]

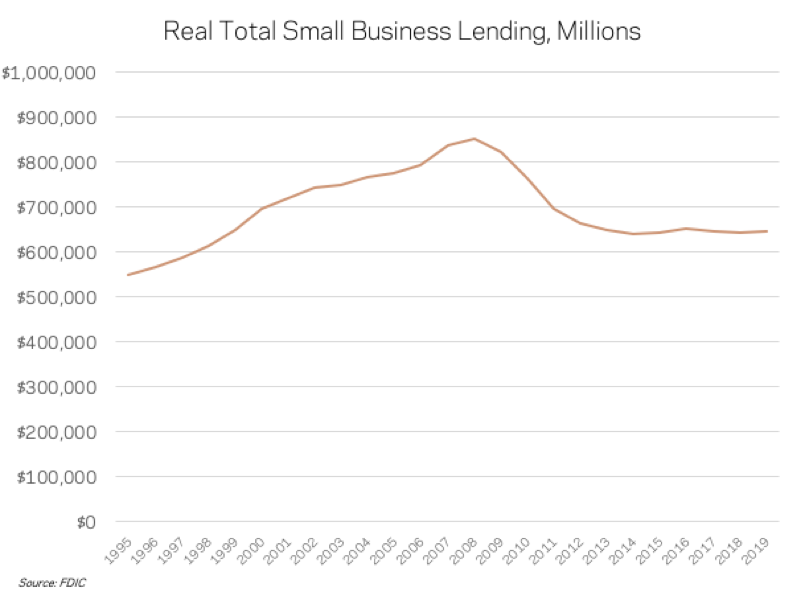

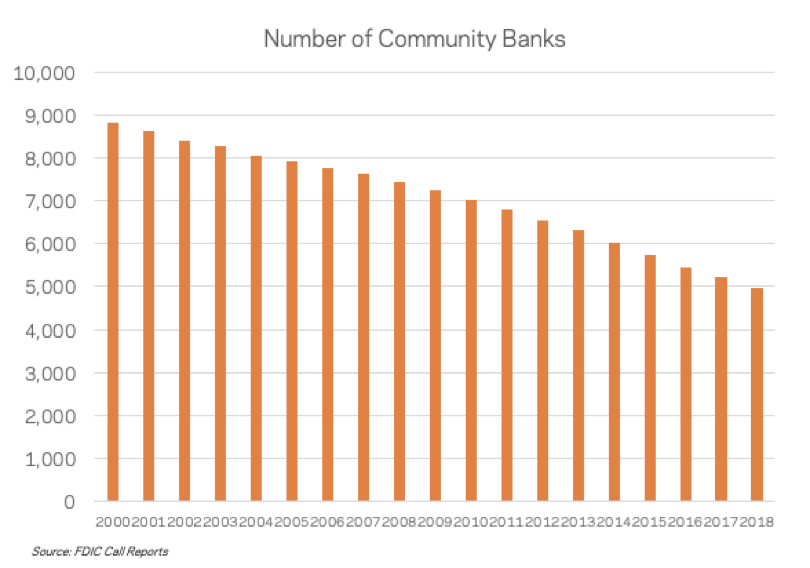

Another challenge faced by Opportunity Zones communities, like many other low-income communities, is capital access. Capital access is an especially critical piece of the puzzle for early stage entrepreneurs, and it is noticeably weak in most Opportunity Zones communities. Entrepreneurs often forgo traditional forms of capital such as bank loans and equity investments, relying instead on personal or familial savings to cover initial startup costs. With an average poverty rate nearly double the national average, Opportunity Zones entrepreneurs are less likely to have access to expendable savings. If they turn to traditional forms of financing, they may run into roadblocks there as well. Not only has small business lending remained frozen since the Great Recession in real terms, but 43 percent of all community banks have disappeared since 2000. There are no commercial banks in nearly half of all Opportunity Zones, and only 5 percent of the total dollar volume of CRA-oriented small business loans under $100,000 occur within Opportunity Zones.[9] Furthermore, it is well documented that the geography of startup financing is very narrow, with roughly 75 percent of venture capital going to just three states each year: New York, California, and Massachusetts.

Opportunity Zones could help fill an important financing gap by incentivizing equity investment in places that have largely struggled to access entrepreneurial growth capital, allowing entrepreneurs to stay and build economic opportunity and wealth for their communities. However, it is important to note that equity capital, while vitally important for the kind of growth-oriented companies that create significant jobs and value in a community, is not the right source of financing for most businesses. The Opportunity Zones is therefore not a panacea for meeting the capital needs of all types of businesses.

Early Opportunity Zones Market Activity

While the Opportunity Zones market is still nascent, most of the early investment has gone into an array of real estate developments. This is due to a number of factors, including the fact that improvements to the built environment is often a crucial first step in bringing people and businesses back into a community. One less benign factor is the continued lack of regulatory clarity governing investments in operating businesses, which I will address later in my testimony.

Even though the marketplace is far from fully formed, the Opportunity Zones incentive is being used to support a wide range of investments across the country just as Congress intended. Investments in clean energy, broadband infrastructure, vertical farming, manufacturing, and industrial facilities are a sign of the long-term potential of the incentive, even if the scale of capital flowing to such investments remains limited. Many early investments are going into basic neighborhood amenities, such as grocery stores in food deserts, medical clinics, and new housing of all different types. Small cities are using Opportunity Zones as a catalyst to build or expand local innovation districts or revitalize blighted downtown corridors. Anchor employers, from Fortune 500 companies to major hospital systems, are helping to jumpstart investment in communities like Cleveland, OH, and Erie, PA

Several early investments are using real estate development to support a stronger local startup ecosystem. For example, Launch Pad, a network of coworking spaces that started in New Orleans, is planning to expand into Opportunity Zones in more than 20 markets over the next year. The company also plans to start an Opportunity Fund to invest in the businesses that occupy their space. In South Los Angeles, SoLa Impact, an affordable housing developer, saw the chance to unlock the entrepreneurial potential of its surrounding community, and is now using Opportunity Zones capital to build “The Beehive,” a five-acre business campus and co-working space in a largely vacant industrial corridor.

Examples like these will proliferate as the rules and best practices for Opportunity Zones become more widely understood among communities, investors, and local businesses. While there are many encouraging signs of activity, I would caution against drawing broad conclusions from anecdotes at such an early stage. Without additional regulatory clarity and much stronger local implementation efforts, this policy will not reach its full potential.

Regulatory Hurdles Limiting Opportunity Zones Financing for Local Businesses

The rulemaking process is now in its final stages, but regulatory concerns are keeping many investors who wish to deploy capital into operating businesses on the sidelines. Specifically, the following technical issues[10] must be addressed in the final regulations in order to avoid repeating the shortcomings of previous federal efforts to support the growth of local businesses in low-income communities:

- Substantial Improvement Test: The “substantial improvement” test is a central feature of the Opportunity Zones legislation, requiring investments in existing businesses or assets to demonstrate significant new economic value creation. However, the draft regulations currently require the substantial improvement test to be assessed on an asset-by-asset – rather than aggregate – basis. This approach is extremely impractical and will hinder the ability for businesses to qualify for Opportunity Zones investment.

- Timing Considerations: Opportunity Funds need adequate time to build a portfolio of qualifying business investments. However, the draft regulations currently provide a window as short as six months for an Opportunity Fund to deploy any capital it receives from its investors. EIG and other commenters have recommended a minimum of one year, which is the same time period allowed under the New Markets Tax Credit.

- Recycling Capital from “Interim Gains”: Congress intended Opportunity Funds to have the ability to operate as true portfolio funds, allowing investors to mitigate risk by pooling capital together and deploying it in a variety of investments. Furthermore, Congress anticipated that an Opportunity Fund would not necessarily hold each of its portfolio investments for the entire duration of the Fund, but would instead make initial investments and then seek to reinvest later as capital was returned to the Fund from the sale of an asset. This is critical for Funds that intend to invest in operating businesses, which are inherently less predictable than real estate projects. However, the current proposed regulations would treat the sale of a business held by an Opportunity Fund as a taxable event for the Fund’s investors even if the proceeds are fully reinvested back into a new qualifying investment. In practice, this means that the sale of an asset held by an Opportunity Fund and the reinvestment of the proceeds back into a designated low-income area could result in a large tax bill for investors who have not yet received a distribution from the fund. This disharmony between the intent of the statute and current rulemaking undermines the utility of the incentive to support local operating businesses.

Unless we sufficiently address these and other key issues, it will be difficult for Opportunity Zones to live up to their full potential to boost investment in local businesses and create new economic opportunities for residents of distressed communities. Instead, it may go the way of previous federal policies that have a generally poor track record of encouraging private investment in businesses, and especially into new firms.

Other Tools are Needed

Opportunity Zones are designed to work alongside existing policy tools to support local businesses and entrepreneurial ecosystems across the country. But the current policy toolkit is woefully inadequate compared to the scale of the challenges.

To that end, I offer the following recommendations.

- Legislative improvements to Opportunity Zones. There are a number of potential legislative changes that Congress may want to consider, ranging from technical corrections to more significant improvements that would enhance the incentive’s benefits to designated communities. But perhaps the most obvious is to enact clear and practical reporting requirements that will help ensure the policy’s impact can be properly evaluated over time. EIG has worked closely with a bipartisan group of lawmakers in the House and Senate on such transparency legislation,[11] and we urge Congress to pass this uncontroversial measure as quickly as possible.

- Technical assistance to Opportunity Zones communities and stakeholders. Communities and local stakeholders need help navigating the use of the Opportunity Zones incentive and developing local implementation strategies. Federal agencies, especially the Small Business Administration (SBA), should be leading such efforts. The SBA should provide much-needed technical assistance to both Opportunity Funds and Opportunity Zone businesses on eligibility requirements, best practices, and other issues to ensure they are equipped to take advantage of the incentive as intended.

- Create new pathways for skilled immigrants to locate in struggling communities. In light of what we now know about the close ties between demographics, population growth, and startup rates, as well as the high propensity of immigrants to become inventors and entrepreneurs, we should recommit to comprehensive reform to our broken immigration system. My view is that a cornerstone of any such package must be a place-based visa – what EIG calls a “Heartland Visa” – that would allow places confronting demographic decline to welcome new skilled immigrants to their communities through a new program designed for community renewal. Such a program would need to be additive to national top-line skilled immigration flows; it could not repurpose existing visas and still achieve the same economic impact. The idea has been endorsed by business leaders and the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

- Limit the use of non-compete agreements. A growing body of research points to one simple way to boost wages, strengthen innovation, enhance competition, and spur greater levels of entrepreneurship – all without enacting any new programs or increasing federal spending: restrict the use of non-compete agreements in all but the narrowest of circumstances. Non-competes reinforce the advantages of incumbency for existing employers, protecting them from competition at the expense of workers and entrepreneurs. Any serious discussion about creating a more vibrant and competitive economy must include non-competes reform.

- Reform the Small Business Administration. The Small Business Administration plays a critical role in providing technical assistance, financing, and resources to small businesses and established industries, but the agency should modernize its policies to better serve entrepreneurs and new startups entering the market. The SBA should focus on high-growth technology and manufacturing companies, and develop better tools to boost American innovation. EIG joined a letter penned by innovation experts in July in support of such modernization proposals.

- Reauthorize the State Small Business Credit Initiative: The State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) was a component of the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 that generated high-impact entrepreneurial activity and investment ecosystems in all different parts of the country. The innately decentralized program built capacity in every state by providing $1.5 billion in flexible financing to intermediaries that disbursed it to entrepreneurs throughout the country, nearly one-third of whom built their companies in low- and moderate-income census tracts like Opportunity Zones. The initiative lapsed in 2017; Congress should reauthorize it or establish a successor.

What I have outlined here are just some of the building blocks of a comprehensive policy toolkit to support American entrepreneurs, restore U.S. economic dynamism, revitalize our communities, and ultimately restore the promise of the American Dream. Non-competes reform would unshackle potential entrepreneurs and tip the scales back in favor of workers and startups, away from incumbent vested interests. SBA reform and a restoration of the SSBCI would modernize federal approaches to supporting our entrepreneurs and business owners and building local capacity with public dollars. Improving Opportunity Zones and empowering communities to strategically deploy the incentive would further unlock private capital and help achieve national scale. And place-based visas would boost the dynamism and economic stability of struggling areas. No single policy, no matter how well-designed, will be sufficient. A coordinated onslaught, however, could make a real difference.

Conclusion

Opportunity Zones is a promising new initiative that will require much additional work to achieve its intended purpose. Rulemaking is not yet complete. Community stakeholders are still finding their footing. The philanthropic community, which could be playing a crucial role in shaping the early market, has been slow to engage at meaningful scale. And investors remain hesitant to make long-term investments in areas they might not have previously considered. That this is hard work should come as no surprise. As a country, we have largely neglected the underlying challenge this policy is designed to help address, allowing thousands of communities and millions of our fellow citizens to deal with the consequences of disinvestment and decline even in the midst of national growth and prosperity. There will be no overnight success stories, but with the right tools and a much greater commitment of resources, I believe Opportunity Zones can be an important first step in a new movement of place-based policymaking.

Thank you and I look forward to taking your questions.

[1] Much of this testimony is taken from the following testimonies:

John Lettieri, “Testimony for Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship Hearing on Small Business and the American Worker,” March 6, 2019

John Lettieri, “Testimony for Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship Hearing on Expanding Opportunities for Small Businesses Through the Tax Code,” October 3, 2018

John Lettieri, “Testimony for Joint Economic Committee Hearing on the Promise of Opportunity Zones,” May 17, 2018

[2] Bipartisan, Bicameral Congressional Letter to Treasury on Opportunity Zones, January 23, 2019

Press Release, Senator Scott Introduces the Bipartisan Investing in Opportunity Act, February 2, 2017

[3] U.S. Census Bureau Business Formation Statistics, High-Propensity Business Applications

[4] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?” Economic Innovation Group (2019).

[5] Fatih Karahan, Benjamin Pugsley, and Aysegul Sahin, “Demographic Origins of the Startup Deficit.” Technical Report. New York Fed, mimeo, 2016 and Manual Adelino, Song Ma, and David Robinson. “Firm age, investment opportunities, and job creation.” The Journal of Finance 72.3 (2017): 999-1038.

[6] Ozimek, et al., “From Managing Decline.”

[7] Hugo Hopenhayn, Julian Neira, and Rish Singhania, From Population Growth to Firm Demographics: Implications for Concentration, Entrepreneurship and the Labor Share.” No. w25382. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018.

[8] See EIG’s “Opportunity Zones Facts and Figures”

[9] EIG Analysis of Community Reinvestment Act data

[10] Several of these recommendations can be found in the EIG Opportunity Zones Coalition’s public comment letter (July 1, 2019)

[11] H.R.2593 – To require the Secretary of the Treasury to collect data and issue a report on the opportunity zone tax incentives enacted by the 2017 tax reform legislation, and for other purposes.

Watch the Full Testimony

By: John W. Lettieri, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)

Introduction[1]

Chairman Kim, Ranking Member Hern, and members of the Committee: Thank you for inviting me to testify regarding how the Opportunity Zones tax benefit can be used to support new and growing businesses in struggling communities.

My name is John Lettieri and I am the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a bipartisan research and advocacy organization focused on the decline of economic dynamism and the growing divides between thriving and struggling American communities.

EIG was a leading proponent of the concept behind Opportunity Zones, and I believe the policy as enacted can provide a new lifeline of much-needed investment to struggling communities nationwide if implemented properly. While the incentive was designed to support a wide variety of needs across communities – from housing, to clean energy, to commercial development – its central purpose[2] was to support new businesses and existing small and medium-sized firms in need of growth capital. My testimony today will focus on the policy, regulatory, and practical steps still necessary to achieving this goal.

The Structure and Goals of Opportunity Zones

While there have been a number of previous federal incentive programs aimed at boosting economic activity in underserved areas, the Opportunity Zones incentive is a sharp departure from past precedent in its scope, flexibility, and structure. Perhaps for this reason, it has generated enormous interest among local leaders, investors, philanthropic organizations, and economic development practitioners. Unlike most other federal programs, this incentive can be used in a variety of ways, making it a potentially important and creative tool for financing a range of economic priorities across many different types of communities. At its core, the policy is intended to support the creation of new economic value within communities, either by establishing something new, such as an operating business or commercial development, or by making large-scale improvements to existing businesses or assets within a community.

The Opportunity Zones incentive provides a series of benefits to taxpayers that reinvest their capital gains into qualifying investments in designated low-income communities. The incentive is designed to reward patient capital, with the most significant benefit kicking in only after 10 years. The communities themselves were selected by governors in each state based upon federal income and poverty criteria. Governors were allowed to designate up to 25 percent of the eligible census tracts as Opportunity Zones, which in turn makes certain investments in those areas eligible for a federal tax benefit. To be eligible, an investment must be made using equity capital and deployed through a “Qualified Opportunity Fund,” which is any investment vehicle specifically organized to make qualifying investments in Opportunity Zones communities per the statute.

As a group, the designated communities have far higher levels of socioeconomic need than required by statute. They are also needier in terms of poverty rates, median family incomes, educational attainment, and a host of other criteria than the cohort of eligible tracts governors did not select. While the need-targeting was in general strong, a small percentage of designations have drawn justifiable criticism for being undeserving of Opportunity Zone status, despite being technically eligible according to U.S. Department of the Treasury standards. Such concerns should inform future legislative efforts to expand or improve the policy.

How the average Opportunity Zone census tract compares to other peer groups

Source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS) Data, 2013-2017

The State of American Entrepreneurship

Before going any further, I want to briefly examine the state of American entrepreneurship and how it relates to the Opportunity Zones initiative.

Policymakers generally devote too much attention to small businesses and not nearly enough to new businesses. One often hears that small businesses are the backbone of U.S. job creation, but it is specifically the small cohort of new businesses that grow and add employees to which most net new job creation can be attributed each year. EIG’s research finds that new business formation was abysmal in the wake of the Great Recession, both in terms of the rate and scale of new firms, as well as the geographic distribution of net firm formation. Yet this decline in entrepreneurship started long ago and is the centerpiece of an economy-wide decline in dynamism that defies popular notions of the current era being one of unprecedented economic change and disruption.

Over the past several decades, the startup rate, defined as the percent of all firms in the economy that started in the past year, has declined across virtually all regions and sectors of the economy. It fell steadily through the 1980s and 1990s before collapsing with the Great Recession. Troublingly, the national economic recovery has done little to improve the rate of business formation. Startup activity finally picked up in 2016, as the rate of new business creation improved to 8.4 percent. Yet even that post-recession high left the startup rate 2 percentage points below its long-run average, which translates to roughly 100,000 “missing” new companies annually.

The latest business application data from the Census Bureau tell us that as recently as the 2nd quarter of 2019, there were 17 percent fewer promising new businesses in the queue than in 2006.[3] The latest figures on actual startups show no real rebound at all between 2010 and 2016, making entrepreneurship one of the few indicators that have failed to meaningfully improve in spite of an ongoing economic expansion. Consider that between 2006 and 2019 real U.S. GDP grew by nearly $4 trillion and our population increased by nearly 30 million, and it becomes clear that the U.S. economy is growing relatively less entrepreneurial every year.

The decline in business dynamism has significant implications for the health of regions and communities. For the three decades prior to 2007, the vast majority of U.S. metro areas saw net increases in local firms each year. This changed dramatically with the Great Recession. Metro-level data from the latest year available, 2014, revealed that 61 percent of U.S. metro areas lost firms that year, meaning too few startups were launched to replace businesses that closed. The trend shows that across much of the country the cycles of churn and creative destruction that keep the economy healthy are breaking down.

Metro areas with increasing (left) and decreasing (right) numbers of firms in 2014

Source: EIG’s “Dynamism in Retreat” and U.S. Census Bureau Business Dynamics Statistics

The slowdown in entrepreneurial activity is even more pronounced in economically struggling communities. EIG’s Distressed Communities Index finds that the typical distressed zip code lost 5 percent of its business establishments from 2012 to 2016. On current trendlines, the same group of zip codes, representing one-fifth of all zip codes in the United States, will never recover the 1.3 million jobs they lost to the Great Recession. While numerous overlapping and complicated forces contribute to these outcomes, it is no coincidence that more entrepreneurial eras in American history were also times of more broadly shared prosperity.

Demographics stand out as a growing headwind for the U.S. economy with significant implications for the future of American entrepreneurship. The United States once enjoyed some of the highest rates of population growth in the developed world. Today, the rate of U.S. population growth stands at its lowest level since the Great Depression and half the level of the early 1990s. Economists have made considerable advances in the past two years explaining how this new development will impact the dynamism of the U.S. economy.

We reviewed the literature on demography and dynamism in a recent report.[4] Two prominent studies demonstrate how the slowing growth and aging of the population leads to fewer new firm starts.[5] An analysis of Moody’s Analytics data found that a 1 percentage point decline in population growth from 2007 to 2017 caused a county’s startup rate to decline by 2-3 percentage points.[6] Another shows how the aging of the large baby boom generation may be contributing to multiple related phenomena: fewer firm starts, an aging firm distribution, a growing concentration of employment into larger firms, and a falling share of national income going to workers.[7] Demographic stagnation and population loss are especially serious concerns for a large share of Opportunity Zones communities, 45 percent of which have lost population over the past decade.[8]

Another challenge faced by Opportunity Zones communities, like many other low-income communities, is capital access. Capital access is an especially critical piece of the puzzle for early stage entrepreneurs, and it is noticeably weak in most Opportunity Zones communities. Entrepreneurs often forgo traditional forms of capital such as bank loans and equity investments, relying instead on personal or familial savings to cover initial startup costs. With an average poverty rate nearly double the national average, Opportunity Zones entrepreneurs are less likely to have access to expendable savings. If they turn to traditional forms of financing, they may run into roadblocks there as well. Not only has small business lending remained frozen since the Great Recession in real terms, but 43 percent of all community banks have disappeared since 2000. There are no commercial banks in nearly half of all Opportunity Zones, and only 5 percent of the total dollar volume of CRA-oriented small business loans under $100,000 occur within Opportunity Zones.[9] Furthermore, it is well documented that the geography of startup financing is very narrow, with roughly 75 percent of venture capital going to just three states each year: New York, California, and Massachusetts.

Opportunity Zones could help fill an important financing gap by incentivizing equity investment in places that have largely struggled to access entrepreneurial growth capital, allowing entrepreneurs to stay and build economic opportunity and wealth for their communities. However, it is important to note that equity capital, while vitally important for the kind of growth-oriented companies that create significant jobs and value in a community, is not the right source of financing for most businesses. The Opportunity Zones is therefore not a panacea for meeting the capital needs of all types of businesses.

Early Opportunity Zones Market Activity

While the Opportunity Zones market is still nascent, most of the early investment has gone into an array of real estate developments. This is due to a number of factors, including the fact that improvements to the built environment is often a crucial first step in bringing people and businesses back into a community. One less benign factor is the continued lack of regulatory clarity governing investments in operating businesses, which I will address later in my testimony.

Even though the marketplace is far from fully formed, the Opportunity Zones incentive is being used to support a wide range of investments across the country just as Congress intended. Investments in clean energy, broadband infrastructure, vertical farming, manufacturing, and industrial facilities are a sign of the long-term potential of the incentive, even if the scale of capital flowing to such investments remains limited. Many early investments are going into basic neighborhood amenities, such as grocery stores in food deserts, medical clinics, and new housing of all different types. Small cities are using Opportunity Zones as a catalyst to build or expand local innovation districts or revitalize blighted downtown corridors. Anchor employers, from Fortune 500 companies to major hospital systems, are helping to jumpstart investment in communities like Cleveland, OH, and Erie, PA

Several early investments are using real estate development to support a stronger local startup ecosystem. For example, Launch Pad, a network of coworking spaces that started in New Orleans, is planning to expand into Opportunity Zones in more than 20 markets over the next year. The company also plans to start an Opportunity Fund to invest in the businesses that occupy their space. In South Los Angeles, SoLa Impact, an affordable housing developer, saw the chance to unlock the entrepreneurial potential of its surrounding community, and is now using Opportunity Zones capital to build “The Beehive,” a five-acre business campus and co-working space in a largely vacant industrial corridor.

Examples like these will proliferate as the rules and best practices for Opportunity Zones become more widely understood among communities, investors, and local businesses. While there are many encouraging signs of activity, I would caution against drawing broad conclusions from anecdotes at such an early stage. Without additional regulatory clarity and much stronger local implementation efforts, this policy will not reach its full potential.

Regulatory Hurdles Limiting Opportunity Zones Financing for Local Businesses

The rulemaking process is now in its final stages, but regulatory concerns are keeping many investors who wish to deploy capital into operating businesses on the sidelines. Specifically, the following technical issues[10] must be addressed in the final regulations in order to avoid repeating the shortcomings of previous federal efforts to support the growth of local businesses in low-income communities:

Unless we sufficiently address these and other key issues, it will be difficult for Opportunity Zones to live up to their full potential to boost investment in local businesses and create new economic opportunities for residents of distressed communities. Instead, it may go the way of previous federal policies that have a generally poor track record of encouraging private investment in businesses, and especially into new firms.

Other Tools are Needed

Opportunity Zones are designed to work alongside existing policy tools to support local businesses and entrepreneurial ecosystems across the country. But the current policy toolkit is woefully inadequate compared to the scale of the challenges.

To that end, I offer the following recommendations.

What I have outlined here are just some of the building blocks of a comprehensive policy toolkit to support American entrepreneurs, restore U.S. economic dynamism, revitalize our communities, and ultimately restore the promise of the American Dream. Non-competes reform would unshackle potential entrepreneurs and tip the scales back in favor of workers and startups, away from incumbent vested interests. SBA reform and a restoration of the SSBCI would modernize federal approaches to supporting our entrepreneurs and business owners and building local capacity with public dollars. Improving Opportunity Zones and empowering communities to strategically deploy the incentive would further unlock private capital and help achieve national scale. And place-based visas would boost the dynamism and economic stability of struggling areas. No single policy, no matter how well-designed, will be sufficient. A coordinated onslaught, however, could make a real difference.

Conclusion

Opportunity Zones is a promising new initiative that will require much additional work to achieve its intended purpose. Rulemaking is not yet complete. Community stakeholders are still finding their footing. The philanthropic community, which could be playing a crucial role in shaping the early market, has been slow to engage at meaningful scale. And investors remain hesitant to make long-term investments in areas they might not have previously considered. That this is hard work should come as no surprise. As a country, we have largely neglected the underlying challenge this policy is designed to help address, allowing thousands of communities and millions of our fellow citizens to deal with the consequences of disinvestment and decline even in the midst of national growth and prosperity. There will be no overnight success stories, but with the right tools and a much greater commitment of resources, I believe Opportunity Zones can be an important first step in a new movement of place-based policymaking.

Thank you and I look forward to taking your questions.

[1] Much of this testimony is taken from the following testimonies:

John Lettieri, “Testimony for Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship Hearing on Small Business and the American Worker,” March 6, 2019

John Lettieri, “Testimony for Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship Hearing on Expanding Opportunities for Small Businesses Through the Tax Code,” October 3, 2018

John Lettieri, “Testimony for Joint Economic Committee Hearing on the Promise of Opportunity Zones,” May 17, 2018

[2] Bipartisan, Bicameral Congressional Letter to Treasury on Opportunity Zones, January 23, 2019

Press Release, Senator Scott Introduces the Bipartisan Investing in Opportunity Act, February 2, 2017

[3] U.S. Census Bureau Business Formation Statistics, High-Propensity Business Applications

[4] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?” Economic Innovation Group (2019).

[5] Fatih Karahan, Benjamin Pugsley, and Aysegul Sahin, “Demographic Origins of the Startup Deficit.” Technical Report. New York Fed, mimeo, 2016 and Manual Adelino, Song Ma, and David Robinson. “Firm age, investment opportunities, and job creation.” The Journal of Finance 72.3 (2017): 999-1038.

[6] Ozimek, et al., “From Managing Decline.”

[7] Hugo Hopenhayn, Julian Neira, and Rish Singhania, From Population Growth to Firm Demographics: Implications for Concentration, Entrepreneurship and the Labor Share.” No. w25382. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018.

[8] See EIG’s “Opportunity Zones Facts and Figures”

[9] EIG Analysis of Community Reinvestment Act data

[10] Several of these recommendations can be found in the EIG Opportunity Zones Coalition’s public comment letter (July 1, 2019)

[11] H.R.2593 – To require the Secretary of the Treasury to collect data and issue a report on the opportunity zone tax incentives enacted by the 2017 tax reform legislation, and for other purposes.

Entrepreneurship| Small Business | Opportunity Zones | Skilled Immigration

Related Posts

How many manufacturing workers are there?

Opportunity Zones 2.0: A Guide for Governors and Mayors

The U.S. Retirement System: Fast Facts