By: John W. Lettieri, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)

Chair Lofgren, Ranking Member McClintock, and members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on the need for immigration reform.

My name is John Lettieri and I am the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a bipartisan research and public policy organization devoted to building a more dynamic and inclusive American economy.

Introduction

The United States is a magnet for educated and entrepreneurial people the world over. It is difficult to fully capture just how deeply this fact matters to the country’s economic well-being, but the benefits are profound and reach into almost every area of American life. In healthcare, the sciences, engineering, arts, technology, and dozens of other fields, immigrants have fueled American dynamism and helped to keep our country young, innovative, and aspirational.

But current skilled immigration policy fails on multiple fronts. It welcomes too few workers overall. It fails to prioritize immigrant entrepreneurs who could build the companies of the future and create jobs for American workers. And it primarily serves to strengthen already successful and fast-growing areas of the country by tying a skilled visa to a single employer, thereby ignoring the needs of legacy cities and rural communities struggling with the effects of population loss and demographic decline. In other words, communities that could most benefit from an infusion of skilled immigrants are least likely to benefit from current policy.

Critics of immigration are right to ask how policy can be changed so that it benefits more Americans, but they are wrong about the changes that are needed. There is broad consensus that decreasing the number of immigrants, as some have proposed, would exacerbate many of our most serious national challenges. Meanwhile, even the most ardent academic critics[1] of immigration acknowledge that it would do nothing to move the dial in favor of the average American worker. In contrast, letting in more highly skilled immigrants would seriously boost overall economic growth and prosperity, and creating new pathways for them to settle in struggling places can help ensure those gains are widely shared.

Accordingly, my testimony today will focus on two ways that immigration reform could deliver meaningful benefits to a broader share of workers and communities: 1) supporting the development of economically and demographically stagnant places; and, 2) bolstering the entrepreneurial dynamism and innovative capacity of the national economy.

I will start by talking about the need for immigration policy that better serves communities grappling with the effects of population loss and demographic stagnation.

Place-based Visas for Struggling Communities

A growing body of research reveals that population growth is an important driver of the health of an economy, not just its size. A growing population stokes demand, providing new and fast-growing firms with needed labor, and spurring the creation of new business models as companies compete for an expanding pool of customers.

For most of its history, the United States enjoyed a young and quickly growing population. However, over the past decade, declining fertility rates, mostly flat immigration rates, and a rapidly aging society have dramatically altered the picture.

Recently released population estimates by the Census Bureau reveal that the U.S. has reached an unprecedented level of demographic stagnation.[2] The estimated 0.35 percent population growth over the period from July 1, 2019, to July 1, 2020, would be the lowest annual growth rate since the turn of the 20th century.[3] Census estimates also suggest that population growth over the last decade may be the lowest recorded in the country’s entire history.[4] To put this in perspective, the country added nearly two million fewer people in 2020 than it did in 2000.[5] William Frey of the Brookings Institution finds that current trends in fertility, mortality, and immigration would lead to a population growth rate between 2020 and 2060 that is only half the rate of the previous four decades.[6] And reinforcing this demographic stagnation is a steep decline in within-U.S. mobility that saw internal migration over the 2010s fall to historic lows.[7]

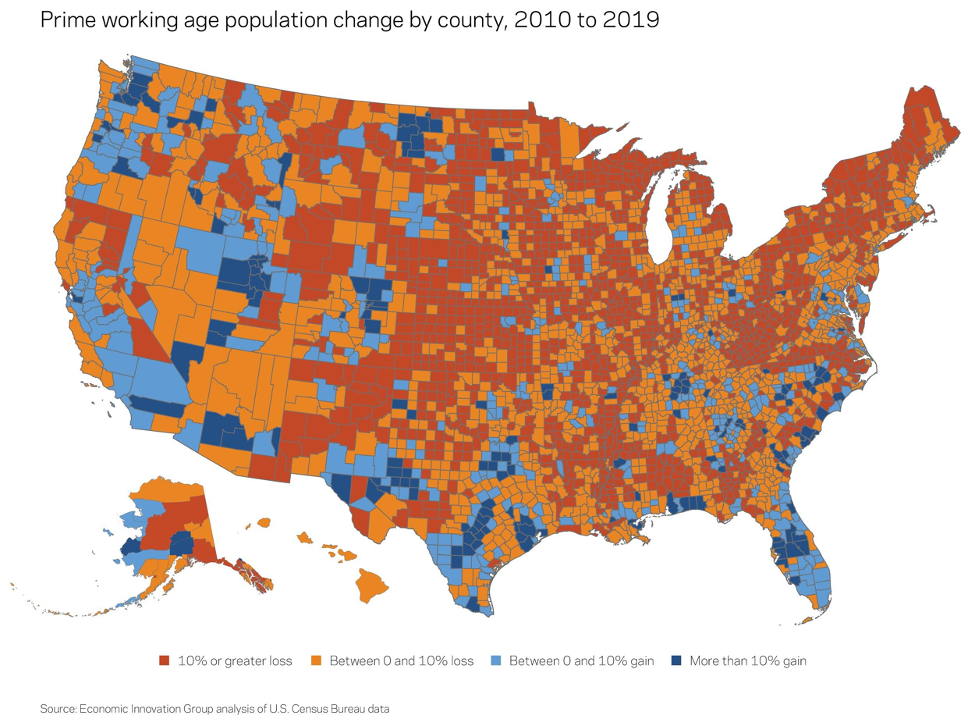

The effects of the national demographic slowdown are felt unevenly across regions. About half of U.S. counties are now experiencing declines in population overall. Fully 81 percent have seen their prime-working-age population (those aged 25 to 54) shrink over the past decade.[8] This trend has hit rural areas the hardest, with 91 percent of rural counties losing prime-age workers over the period.[9] By 2037, an estimated two-thirds of U.S. counties will have fewer prime-working-age adults than they did four decades earlier in 1997.[10] In other words, the consequences of demographic decline are only just beginning to take shape throughout the economy.

What can be done in response to these seismic shifts? Alongside policies that make it easier to start and support a family,[11] immigration policy is one of the few and most obvious ways to counter demographic decline.

Immigrants — skilled immigrants, in particular — bring an array of benefits to declining communities. They fill empty housing stock, reduce crime rates and spur new business creation. Where there is a shrinking tax base, they bring fiscal stability for schools and first responders. Where there is a dwindling local workforce, immigrants enable employers to expand. Where there are shuttered Main Street storefronts, immigrants start new businesses and add vibrancy to local commerce. Many struggling cities have underused assets and infrastructure built for much larger populations; new immigrants activate such latent capacity. But unfortunately, current U.S. policy does little to connect skilled immigrants with the kinds of legacy cities, small towns, and rural communities that would benefit from their presence the most.[12]

To fix this, EIG has called for a geographically targeted visa program — a “Heartland Visa” — aimed directly at helping struggling areas break the cycle of economic and demographic decline.[13] (The idea of “place-based” — rather than employer-based — visas has been already implemented in advanced countries such as Canada and Australia.[14]) Such a program would open a new door — without reducing the number of visas available through other programs — for skilled workers who could meet a range of local needs, from helping grow a local robotics hub, to filling small-town physician shortages. But instead of relying on employer sponsorship, Heartland Visas would be tied to communities — ones that qualify for the program based on a stagnant or shrinking local workforce, or other economic criteria. As a result, local startups, small businesses, and medium-sized enterprises would gain access to a talent pool typically reserved under current policy for big businesses in booming areas.[15]

To participate in the program, eligible communities would be required to opt in and commit resources — matched by federal dollars — to implement the program and support new arrivals. Welcoming communities would rally to attract human capital much as they do for a new corporate headquarters — by showcasing their local amenities, quality of life, job opportunities and growth potential. Each community would employ its local knowledge, sponsoring entities, and anchor institutions in developing its own implementation strategy. And the draw could be considerable. Many demographically stagnant U.S. communities offer an enormously attractive chance for a better life for would-be immigrants.

Visa holders, in turn, would commit to settle in an eligible community for a set period — say, three years — in exchange for being fast-tracked for a green card and permanent status. They would have a wide array of choices for where to settle and full job mobility within their chosen labor market. While some visa holders would eventually relocate, there is strong evidence[16] that many would put down permanent roots.[17] Over time, areas that succeed in implementing this program would find it easier to attract and retain native born workers as well — and with them, the businesses that rely upon a skilled and knowledgeable local workforce. What’s more, Heartland Visas wouldn’t simply add to a community’s population; they would add the kind of workers disproportionately likely to become entrepreneurs and drive growth themselves. In that sense, this proposal would work particularly well alongside the popular idea of a startup visa, which I will address later in my testimony.

The opt-in nature of the Heartland Visa concept is one of its most important features. Placing agency in the hands of communities would encourage them to view immigration for what it truly is: a powerful catalyst for economic growth. Such a policy would reject the false choice between compassion and self-interest by aligning the needs of struggling areas with the aspirations of those looking to build a better life in our country. Perhaps this is why this idea has already attracted widespread support, including the endorsement of the U.S. Conference of Mayors on a broad bipartisan basis.

Entrepreneurship Visa

The second area of focus for my testimony deals with how immigration reform can support American entrepreneurship.

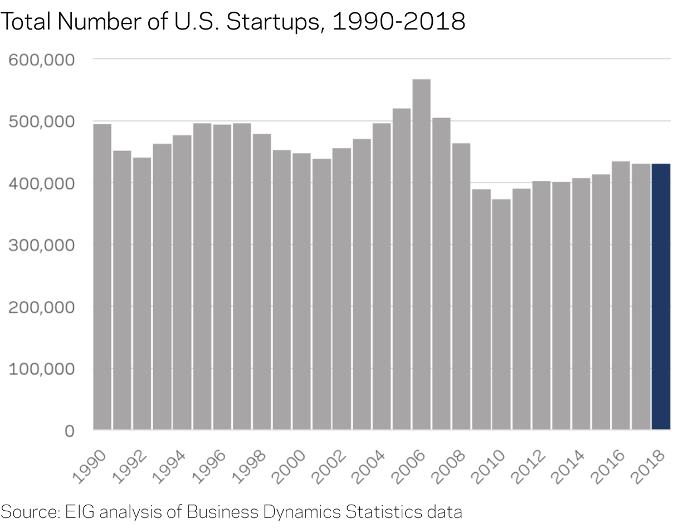

First, it is important to explain why entrepreneurship should be a priority. New businesses are major drivers of American job creation, accounting for the majority of net new jobs created throughout the economy each year. New businesses are a vital source of competition within industries, forcing incumbents to adapt and improve, or else be left behind. And young, high-growth firms also increase demand for American workers, setting off a chain reaction that leads to more opportunities throughout the labor market for everyone.

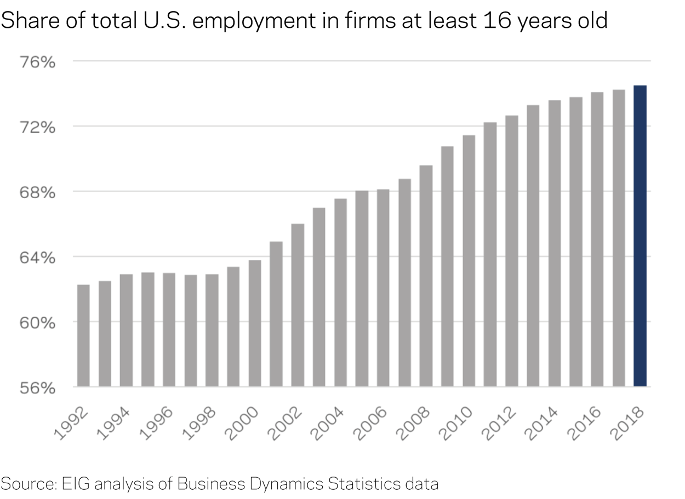

For all these reasons, it should deeply concern policymakers that the U.S. startup rate has failed to recover from the steep decline it experienced during the Great Recession. The 2010s were a “startup-less” recovery during which the rate of firm formation remained startlingly and persistently low. Making matters worse, the geographic distribution of net new firms became highly concentrated in a handful of large metro areas, with large shares of U.S. metro areas seeing their stock of firms shrink even as the national economy continued its recovery.

Immigrants bolster entrepreneurship in two important ways. First, as noted earlier, they help to counter population loss, which is shown to hamper business formation. For example, our research found that, at the county level, one percentage point lower average annual population growth from 2007 to 2017 likely caused the rate of business formation to decline by two to three percentage points over the same period.[18]

Immigrants are also disproportionately likely to become entrepreneurs. Roughly one in four U.S. entrepreneurs is an immigrant.[19] Research by the Kauffman Foundation finds that immigrants are nearly twice as likely to start a business as native-born Americans.[20] The Center for American Entrepreneurship found that over 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies in 2017 were founded by an immigrant or the child of immigrants. Those firms alone employed 12.8 million people worldwide and accounted for $5.3 trillion in global revenue in 2016.[21] The race for a Covid-19 vaccine has provided the latest high-profile example of how immigrant founders contribute to U.S. well-being: Both Moderna and Pfizer, two of the first companies to win approval for a vaccine, have immigrant founders and CEOs.

Immigrants in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) also contribute in profound ways to U.S. productivity growth. One estimate found that STEM immigrants were responsible for 30 percent to 50 percent of all U.S. productivity growth from 1990 to 2010.[22] That study also finds that an increase in the foreign STEM share of a city’s workforce increased the wages of native college graduates and non-college educated workers alike — with no significant effects on employment.

The overwhelming evidence suggests we should be doing much more to boost inflows of skilled immigrants. In particular, immigration reform should establish a new program to provide visas for immigrant entrepreneurs. In this regard, the U.S. lags behind other advanced economies, such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Spain, and the UK. In total, more than a dozen countries have some form of a “startup visa” to welcome the kind of talent the U.S. turns away.

If policymakers are truly concerned about ensuring a strong job market for American workers, it is difficult to think of a more obvious solution than actively recruiting entrepreneurs whose firms will increase labor demand. One noteworthy proposal is the 2019 “Startup Act,” sponsored by Senators Moran (R-KS), Warner (D-VA), Blunt (R-MO), and Klobuchar (D-MN). This bipartisan legislation would establish large pools of both entrepreneur and STEM visas to help the U.S. attract and retain the kind of workers that help keep our economy the most dynamic and innovative in the world. Based on everything we know about the impact of skilled immigration, there is little doubt that the Startup Act would lead to a wealth of job creation and strengthen the innovation-intensive sectors of our economy.

Conclusion

It is to our great advantage that people around the world see the United States as a beacon of opportunity, but we have simply failed to apply this advantage to solving our most deep-seated economic challenges. As this committee considers ways to reform and improve immigration policy, I urge you to prioritize establishing new programs to support the economic needs of struggling communities and bolster American entrepreneurship.

Thank you for your consideration.

Appendix

Key Principles for a Heartland Visa Program

A place-based Heartland Visa (HV) program should be anchored in a number of key principles:

- Communities should only be eligible for HVs if they “opt in” on a voluntary basis.

- HVs should be targeted to places confronting chronic population stagnation or loss as a means of boosting economic dynamism and fiscal stability. HVs would help stagnant areas build on existing strengths while seeding new ones. And they would be instrumental in putting underutilized local assets back to productive use.

- HVs should be additive to top-line national skilled immigration quotas. HVs should open a new door through which human capital can enter the United States and contribute to the economy.

- HVs should be designed to serve as a catalyst for parts of the country currently underserved by existing programs, such as the H-1B.

- Rather than being tied to a single employer, HV holders should be allowed to compete on the open labor market to maximize their availability to startups and small businesses that may struggle with the administrative burden of H-1Bs.

- HVs should be contingent on visa holders finding and maintaining a job or starting a business in an eligible area within a reasonable period of time.

- HVs should provide a fast-tracked path to permanent residency and only restrict where visa holders can live and work for a period of time. During that time they would build social networks and put down roots in their host communities but, once granted permanent residency, visa holders could relocate where they please within the United States. The prospect of permanent residency and full mobility should provide an extremely strong incentive for compliance.

[1] Bryan Caplan, “Borjas, Wages, and Immigration: The Complete Story,” 2007.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau’s Population and Housing Unit Estimates, 2020.

[3] The official Census count for 2020 is still being finalized.

[4] William Frey, “The 2010s saw the lowest population growth in U.S. history, new census estimates show,” Brookings Institution, 2020.

[5] Economic Innovation Group analysis of U.S. Census Bureau population estimates. See Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[6] William Frey, “What the 2020 census will reveal about America: Stagnating growth, an aging population, and youthful diversity,” Brookings Institution, 2021.

[7] William Frey, “Just before COVID-19, American migration hit a 73-year low,” Brookings Institution, 2020.

[8] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[9] August Benzow, “Dramatically curbing legal immigration threatens the health of the U.S. economy,” Economic Innovation Group, 2020.

[10] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[11] For more on declining fertility rates, see Claire Cain Miller, “Americans Are Having Fewer Babies. They Told Us Why,” New York Times, 2018; see also Lyman Stone, “American Women Are Having Fewer Children Than They’d Like,” New York Times, 2018.

[12] John Lettieri, “Opinion: Want to fix the United States’ immigration and economic challenges? Try place-based visas.,” The Washington Post, 2019.[13] See the Appendix for more details on how a Heartland Visa program could be structured.

[14] The idea of a geographically tied visa program has been proposed in the U.S., as well. Senator Ron Johnson (R-WI) introduced the State Sponsored Visa Pilot Program Act of 2017 to create a three-year, renewable nonimmigrant visa for state-sponsored immigrants. Additionally, in 2014, Michigan’s former governor requested 50,000 visas for high-skilled immigrants to settle in Detroit in an effort to bolster the city’s struggling economy.[15] Matthew J. Slaughter, “Immigrants for the Heartland,” Wall Street Journal, 2019.

[16] For evidence from Canada, see “Evaluation of the Provincial Nominee Program,” Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, 2017.

[17] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[18] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[19] Sari Pekkala Kerr and William Kerr, “Immigrant Entrepreneurship,” 2016.

[20] Kauffman Foundation, “Kauffman Compilation: Research on Immigration and Entrepreneurship,” 2016.

[21] Center for American Entrepreneurship, “Immigrant Founders of the Fortune 500.”

[22] Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber, “STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in US Cities,” 2015.

By: John W. Lettieri, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)

Chair Lofgren, Ranking Member McClintock, and members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on the need for immigration reform.

My name is John Lettieri and I am the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a bipartisan research and public policy organization devoted to building a more dynamic and inclusive American economy.

Introduction

The United States is a magnet for educated and entrepreneurial people the world over. It is difficult to fully capture just how deeply this fact matters to the country’s economic well-being, but the benefits are profound and reach into almost every area of American life. In healthcare, the sciences, engineering, arts, technology, and dozens of other fields, immigrants have fueled American dynamism and helped to keep our country young, innovative, and aspirational.

But current skilled immigration policy fails on multiple fronts. It welcomes too few workers overall. It fails to prioritize immigrant entrepreneurs who could build the companies of the future and create jobs for American workers. And it primarily serves to strengthen already successful and fast-growing areas of the country by tying a skilled visa to a single employer, thereby ignoring the needs of legacy cities and rural communities struggling with the effects of population loss and demographic decline. In other words, communities that could most benefit from an infusion of skilled immigrants are least likely to benefit from current policy.

Critics of immigration are right to ask how policy can be changed so that it benefits more Americans, but they are wrong about the changes that are needed. There is broad consensus that decreasing the number of immigrants, as some have proposed, would exacerbate many of our most serious national challenges. Meanwhile, even the most ardent academic critics[1] of immigration acknowledge that it would do nothing to move the dial in favor of the average American worker. In contrast, letting in more highly skilled immigrants would seriously boost overall economic growth and prosperity, and creating new pathways for them to settle in struggling places can help ensure those gains are widely shared.

Accordingly, my testimony today will focus on two ways that immigration reform could deliver meaningful benefits to a broader share of workers and communities: 1) supporting the development of economically and demographically stagnant places; and, 2) bolstering the entrepreneurial dynamism and innovative capacity of the national economy.

I will start by talking about the need for immigration policy that better serves communities grappling with the effects of population loss and demographic stagnation.

Place-based Visas for Struggling Communities

A growing body of research reveals that population growth is an important driver of the health of an economy, not just its size. A growing population stokes demand, providing new and fast-growing firms with needed labor, and spurring the creation of new business models as companies compete for an expanding pool of customers.

For most of its history, the United States enjoyed a young and quickly growing population. However, over the past decade, declining fertility rates, mostly flat immigration rates, and a rapidly aging society have dramatically altered the picture.

Recently released population estimates by the Census Bureau reveal that the U.S. has reached an unprecedented level of demographic stagnation.[2] The estimated 0.35 percent population growth over the period from July 1, 2019, to July 1, 2020, would be the lowest annual growth rate since the turn of the 20th century.[3] Census estimates also suggest that population growth over the last decade may be the lowest recorded in the country’s entire history.[4] To put this in perspective, the country added nearly two million fewer people in 2020 than it did in 2000.[5] William Frey of the Brookings Institution finds that current trends in fertility, mortality, and immigration would lead to a population growth rate between 2020 and 2060 that is only half the rate of the previous four decades.[6] And reinforcing this demographic stagnation is a steep decline in within-U.S. mobility that saw internal migration over the 2010s fall to historic lows.[7]

The effects of the national demographic slowdown are felt unevenly across regions. About half of U.S. counties are now experiencing declines in population overall. Fully 81 percent have seen their prime-working-age population (those aged 25 to 54) shrink over the past decade.[8] This trend has hit rural areas the hardest, with 91 percent of rural counties losing prime-age workers over the period.[9] By 2037, an estimated two-thirds of U.S. counties will have fewer prime-working-age adults than they did four decades earlier in 1997.[10] In other words, the consequences of demographic decline are only just beginning to take shape throughout the economy.

What can be done in response to these seismic shifts? Alongside policies that make it easier to start and support a family,[11] immigration policy is one of the few and most obvious ways to counter demographic decline.

Immigrants — skilled immigrants, in particular — bring an array of benefits to declining communities. They fill empty housing stock, reduce crime rates and spur new business creation. Where there is a shrinking tax base, they bring fiscal stability for schools and first responders. Where there is a dwindling local workforce, immigrants enable employers to expand. Where there are shuttered Main Street storefronts, immigrants start new businesses and add vibrancy to local commerce. Many struggling cities have underused assets and infrastructure built for much larger populations; new immigrants activate such latent capacity. But unfortunately, current U.S. policy does little to connect skilled immigrants with the kinds of legacy cities, small towns, and rural communities that would benefit from their presence the most.[12]

To fix this, EIG has called for a geographically targeted visa program — a “Heartland Visa” — aimed directly at helping struggling areas break the cycle of economic and demographic decline.[13] (The idea of “place-based” — rather than employer-based — visas has been already implemented in advanced countries such as Canada and Australia.[14]) Such a program would open a new door — without reducing the number of visas available through other programs — for skilled workers who could meet a range of local needs, from helping grow a local robotics hub, to filling small-town physician shortages. But instead of relying on employer sponsorship, Heartland Visas would be tied to communities — ones that qualify for the program based on a stagnant or shrinking local workforce, or other economic criteria. As a result, local startups, small businesses, and medium-sized enterprises would gain access to a talent pool typically reserved under current policy for big businesses in booming areas.[15]

To participate in the program, eligible communities would be required to opt in and commit resources — matched by federal dollars — to implement the program and support new arrivals. Welcoming communities would rally to attract human capital much as they do for a new corporate headquarters — by showcasing their local amenities, quality of life, job opportunities and growth potential. Each community would employ its local knowledge, sponsoring entities, and anchor institutions in developing its own implementation strategy. And the draw could be considerable. Many demographically stagnant U.S. communities offer an enormously attractive chance for a better life for would-be immigrants.

Visa holders, in turn, would commit to settle in an eligible community for a set period — say, three years — in exchange for being fast-tracked for a green card and permanent status. They would have a wide array of choices for where to settle and full job mobility within their chosen labor market. While some visa holders would eventually relocate, there is strong evidence[16] that many would put down permanent roots.[17] Over time, areas that succeed in implementing this program would find it easier to attract and retain native born workers as well — and with them, the businesses that rely upon a skilled and knowledgeable local workforce. What’s more, Heartland Visas wouldn’t simply add to a community’s population; they would add the kind of workers disproportionately likely to become entrepreneurs and drive growth themselves. In that sense, this proposal would work particularly well alongside the popular idea of a startup visa, which I will address later in my testimony.

The opt-in nature of the Heartland Visa concept is one of its most important features. Placing agency in the hands of communities would encourage them to view immigration for what it truly is: a powerful catalyst for economic growth. Such a policy would reject the false choice between compassion and self-interest by aligning the needs of struggling areas with the aspirations of those looking to build a better life in our country. Perhaps this is why this idea has already attracted widespread support, including the endorsement of the U.S. Conference of Mayors on a broad bipartisan basis.

Entrepreneurship Visa

The second area of focus for my testimony deals with how immigration reform can support American entrepreneurship.

First, it is important to explain why entrepreneurship should be a priority. New businesses are major drivers of American job creation, accounting for the majority of net new jobs created throughout the economy each year. New businesses are a vital source of competition within industries, forcing incumbents to adapt and improve, or else be left behind. And young, high-growth firms also increase demand for American workers, setting off a chain reaction that leads to more opportunities throughout the labor market for everyone.

For all these reasons, it should deeply concern policymakers that the U.S. startup rate has failed to recover from the steep decline it experienced during the Great Recession. The 2010s were a “startup-less” recovery during which the rate of firm formation remained startlingly and persistently low. Making matters worse, the geographic distribution of net new firms became highly concentrated in a handful of large metro areas, with large shares of U.S. metro areas seeing their stock of firms shrink even as the national economy continued its recovery.

Immigrants bolster entrepreneurship in two important ways. First, as noted earlier, they help to counter population loss, which is shown to hamper business formation. For example, our research found that, at the county level, one percentage point lower average annual population growth from 2007 to 2017 likely caused the rate of business formation to decline by two to three percentage points over the same period.[18]

Immigrants are also disproportionately likely to become entrepreneurs. Roughly one in four U.S. entrepreneurs is an immigrant.[19] Research by the Kauffman Foundation finds that immigrants are nearly twice as likely to start a business as native-born Americans.[20] The Center for American Entrepreneurship found that over 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies in 2017 were founded by an immigrant or the child of immigrants. Those firms alone employed 12.8 million people worldwide and accounted for $5.3 trillion in global revenue in 2016.[21] The race for a Covid-19 vaccine has provided the latest high-profile example of how immigrant founders contribute to U.S. well-being: Both Moderna and Pfizer, two of the first companies to win approval for a vaccine, have immigrant founders and CEOs.

Immigrants in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) also contribute in profound ways to U.S. productivity growth. One estimate found that STEM immigrants were responsible for 30 percent to 50 percent of all U.S. productivity growth from 1990 to 2010.[22] That study also finds that an increase in the foreign STEM share of a city’s workforce increased the wages of native college graduates and non-college educated workers alike — with no significant effects on employment.

The overwhelming evidence suggests we should be doing much more to boost inflows of skilled immigrants. In particular, immigration reform should establish a new program to provide visas for immigrant entrepreneurs. In this regard, the U.S. lags behind other advanced economies, such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Spain, and the UK. In total, more than a dozen countries have some form of a “startup visa” to welcome the kind of talent the U.S. turns away.

If policymakers are truly concerned about ensuring a strong job market for American workers, it is difficult to think of a more obvious solution than actively recruiting entrepreneurs whose firms will increase labor demand. One noteworthy proposal is the 2019 “Startup Act,” sponsored by Senators Moran (R-KS), Warner (D-VA), Blunt (R-MO), and Klobuchar (D-MN). This bipartisan legislation would establish large pools of both entrepreneur and STEM visas to help the U.S. attract and retain the kind of workers that help keep our economy the most dynamic and innovative in the world. Based on everything we know about the impact of skilled immigration, there is little doubt that the Startup Act would lead to a wealth of job creation and strengthen the innovation-intensive sectors of our economy.

Conclusion

It is to our great advantage that people around the world see the United States as a beacon of opportunity, but we have simply failed to apply this advantage to solving our most deep-seated economic challenges. As this committee considers ways to reform and improve immigration policy, I urge you to prioritize establishing new programs to support the economic needs of struggling communities and bolster American entrepreneurship.

Thank you for your consideration.

Appendix

Key Principles for a Heartland Visa Program

A place-based Heartland Visa (HV) program should be anchored in a number of key principles:

[1] Bryan Caplan, “Borjas, Wages, and Immigration: The Complete Story,” 2007.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau’s Population and Housing Unit Estimates, 2020.

[3] The official Census count for 2020 is still being finalized.

[4] William Frey, “The 2010s saw the lowest population growth in U.S. history, new census estimates show,” Brookings Institution, 2020.

[5] Economic Innovation Group analysis of U.S. Census Bureau population estimates. See Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[6] William Frey, “What the 2020 census will reveal about America: Stagnating growth, an aging population, and youthful diversity,” Brookings Institution, 2021.

[7] William Frey, “Just before COVID-19, American migration hit a 73-year low,” Brookings Institution, 2020.

[8] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[9] August Benzow, “Dramatically curbing legal immigration threatens the health of the U.S. economy,” Economic Innovation Group, 2020.

[10] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[11] For more on declining fertility rates, see Claire Cain Miller, “Americans Are Having Fewer Babies. They Told Us Why,” New York Times, 2018; see also Lyman Stone, “American Women Are Having Fewer Children Than They’d Like,” New York Times, 2018.

[12] John Lettieri, “Opinion: Want to fix the United States’ immigration and economic challenges? Try place-based visas.,” The Washington Post, 2019.[13] See the Appendix for more details on how a Heartland Visa program could be structured.

[14] The idea of a geographically tied visa program has been proposed in the U.S., as well. Senator Ron Johnson (R-WI) introduced the State Sponsored Visa Pilot Program Act of 2017 to create a three-year, renewable nonimmigrant visa for state-sponsored immigrants. Additionally, in 2014, Michigan’s former governor requested 50,000 visas for high-skilled immigrants to settle in Detroit in an effort to bolster the city’s struggling economy.[15] Matthew J. Slaughter, “Immigrants for the Heartland,” Wall Street Journal, 2019.

[16] For evidence from Canada, see “Evaluation of the Provincial Nominee Program,” Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, 2017.

[17] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[18] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?,” Economic Innovation Group, 2019.

[19] Sari Pekkala Kerr and William Kerr, “Immigrant Entrepreneurship,” 2016.

[20] Kauffman Foundation, “Kauffman Compilation: Research on Immigration and Entrepreneurship,” 2016.

[21] Center for American Entrepreneurship, “Immigrant Founders of the Fortune 500.”

[22] Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber, “STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in US Cities,” 2015.

Entrepreneurship| Skilled Immigration

Related Posts

State Noncompete Law Tracker

Are Opportunity Zones Helping High-Need Communities? EIG Responds to New York Times Op-Ed

The U.S. loses most international graduates it trains. That problem is about to get worse.