Florida nominated Opportunity Zones in the very same areas targeted by a nationally-recognized neighborhood revitalization nonprofit. Is this a scandal?

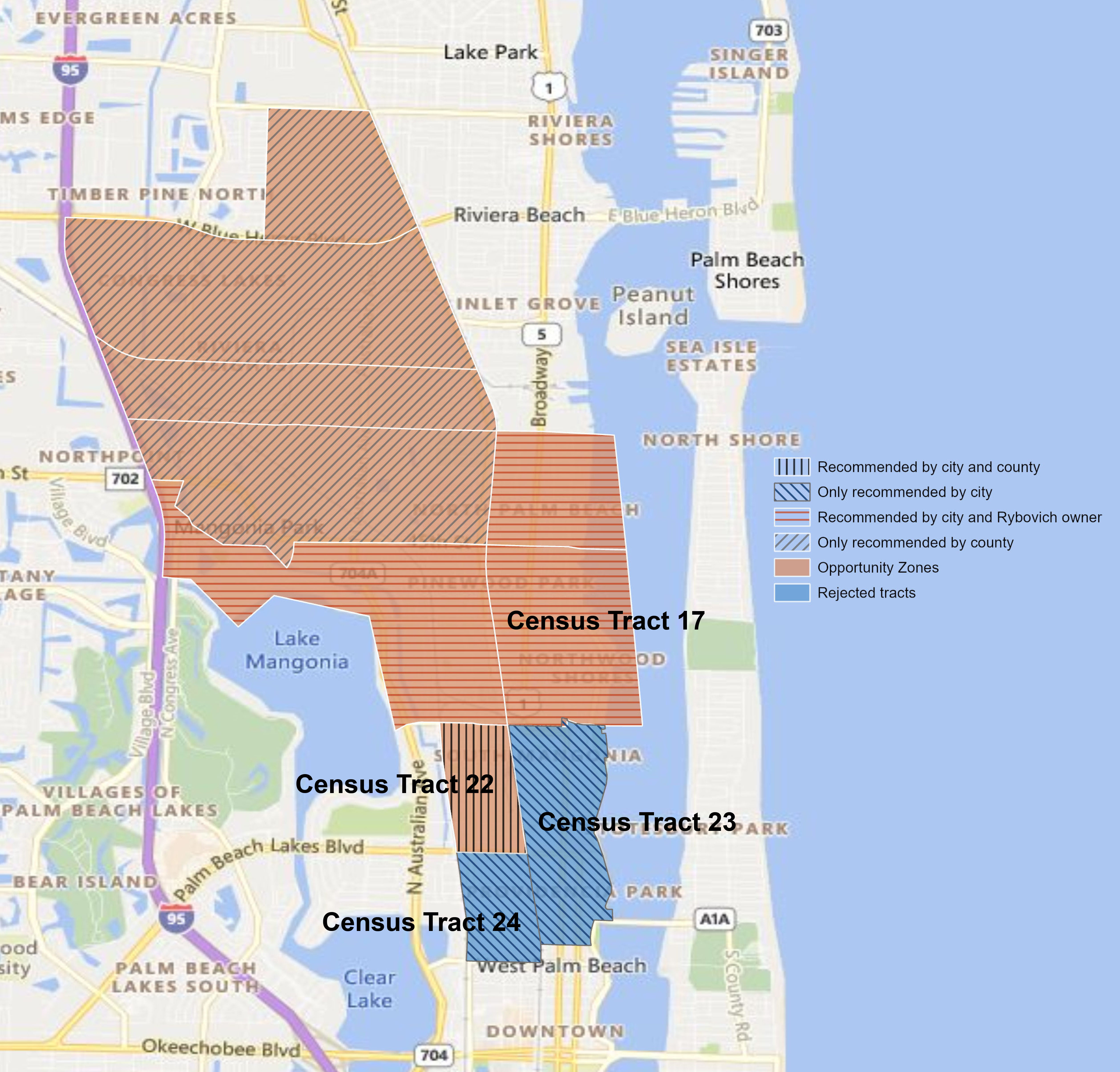

ProPublica’s recent analysis of Opportunity Zones in Florida’s West Palm Beach community has drawn widespread attention as a supposedly flagrant example of abuse of a policy intended to encourage new investment in low-income, high-poverty, and disinvested areas of the country. At first glance, the story seems to have the hallmarks of a scandal: a connected billionaire, a luxury marina, and a selection process that left some eligible neighborhoods off the final list of state designations.

We were intrigued, so we decided to do a bit of digging. It didn’t take long to find much more to this story than ProPublica revealed to its readers.

Background on Florida’s Opportunity Zones

Demographic Data, Florida and the United States

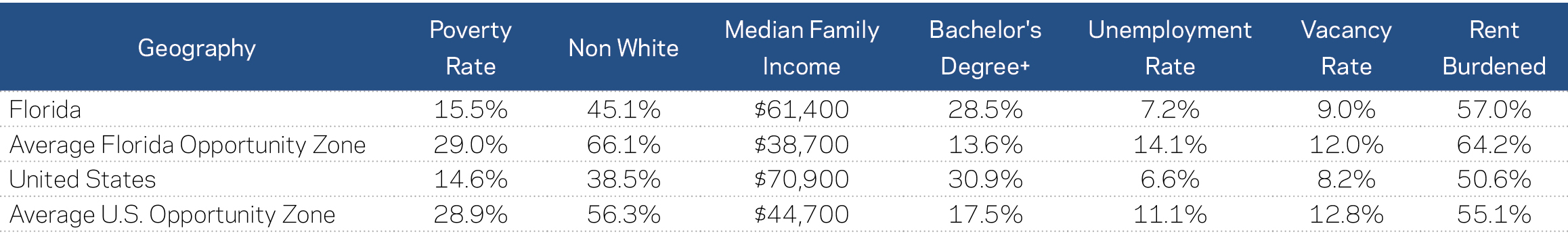

Before diving into the specifics of the ProPublica story, let’s look at the broader landscape of Florida’s Opportunity Zones.

In total, Florida nominated 427 census tracts to be Opportunity Zones, representing 10 percent of all census tracts in the state. Under the federal law, census tracts that meet the U.S. Treasury Department’s standard of a “low-income community” — generally based upon poverty rate and median family income (MFI) — were eligible for designation as Opportunity Zones. It’s important to note that not every eligible tract could be nominated. Instead, governors were tasked with down-selecting to no more than 25 percent of the total number of eligible low-income communities. In Florida, the process was led by the professionals in the state’s Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO). DEO added additional criteria to the federal requirements, taking into consideration factors such as population density and unemployment rates. Results from the quantitative exercise were filtered further with qualitative feedback from municipal and county governments, regional planning councils, nonprofits, developers, and investors.

As a group, Florida’s Opportunity Zones are especially high-need and more diverse than the state as a whole. They have a poverty rate of 29 percent and an average median family income (MFI) of $38,700, and two-thirds of their residents are non-white. By comparison, Florida has a poverty rate of 15 percent and an MFI of $61,400, and is 45 percent non-white. Although states were allowed to nominate up to 5 percent of their Opportunity Zones according to a “contiguous tracts” provision that incorporated adjacent areas with lower levels of economic need, Florida was one of just a few states to not nominate any such tracts. The state instead chose to focus exclusively on areas that met the low-income community standard.

What’s Up with Census Tract 17?

ProPublica’s story hinges on the merits of Census Tract 17 in Palm Beach County, Florida. As far as urban census tracts go, Census Tract 17 exemplifies the massive economic disparities that can play out even within the narrow boundaries of a census tract. Central to the ProPublica narrative is the fact that this tract is home to the Rybovich Marina, a so-called “superyacht marina” that caters to the ultrarich, occupying the eastern corner of the tract. The story leaves readers with the impression that, due to the presence of the marina, this area isn’t really in need of an economic boost, and that its selection as an Opportunity Zone was an obvious abuse of the policy. This would indeed be cause for concern if it were true. Is it?

To answer that, we first need to know whether Census Tract 17 deserved consideration by the state on its own merits — absent any advocacy from local investors or other interests. The simple answer: it did. ProPublica portrays it as “wealthier and whiter” than two other areas under consideration, which, while technically accurate, is a rather twisted way to describe an area with a poverty rate of 23 percent and an MFI of merely $46,791 that happens to be 60 percent non-white (ProPublica doesn’t include these statistics in its story).

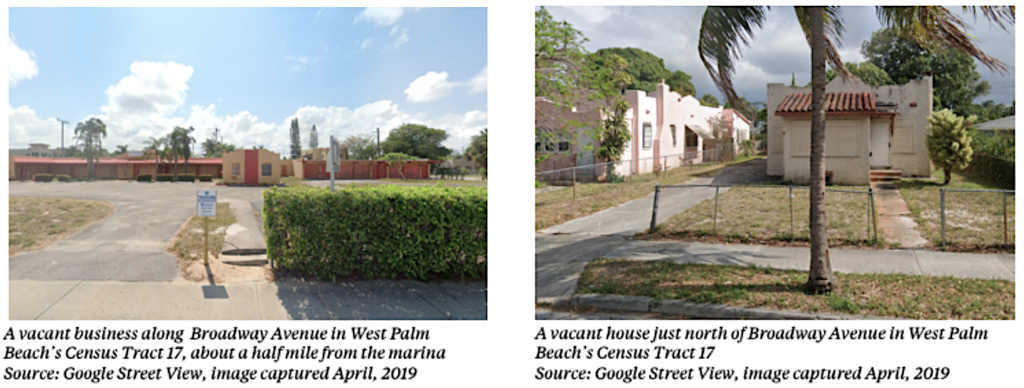

With those numbers, Tract 17 easily qualified for Opportunity Zones designation. Indeed, by any reasonable standard, it is a neighborhood in need of more investment and economic opportunities for its residents. Across the street from the marina is Northboro Elementary school, where 93 percent of students are non-white and 73 percent of students qualify for free lunch. 25 percent of children in the tract live in poverty, compared to 20 percent county-wide. While the wealthy have a foothold along the waterfront (limited to the marina and a smattering of mansions), just a block or two west there are unmistakable signs of poverty and disinvestment. Broadway Avenue, the main commercial strip serving the neighborhood, is lined with vacant lots and shuttered businesses, interspersed with a few restaurants, rundown hotels and small format markets. Using Google Street View to survey Broadway Avenue reveals a high number of vacant storefronts, and the tract has an unemployment rate of 14 percent, double the county’s unemployment rate of 7 percent. This local context was omitted from ProPublica’s story.

ProPublica curiously minimizes the fact that at the time of nomination, Census Tract 17 was the focus of a major neighborhood revitalization effort involving the widely-respected national non-profit, Purpose Built Communities (PBC). The initiative concentrated on the area of West Palm Beach north of 36th Street, half of which falls within the boundaries of Census Tract 17. In fact, all of the census tracts that the Rybovich Marina’s owner recommended to the governor were aligned with the PBC initiative. Why? Perhaps because his firm is involved in supporting PBC’s efforts, as mentioned prominently in his letter, which also references the support of several major anchor institutions in the area.

A spokesperson for the Northend Coalition of Neighborhoods, a West Palm Beach community organization, explains why these areas were targeted by the initiative: the southern areas of West Palm Beach closer to downtown had begun to see redevelopment, but the northern neighborhoods were still stuck. In this light, the selection of Census Tract 17 and its peers covered by the PBC initiative makes clear sense, given that the Opportunity Zones incentive has the best chance of catalyzing inclusive growth when it is aligned with other community-based redevelopment efforts. Perhaps that very same rationale motivated Lift Orlando to nominate the PBC-supported communities in its backyard to become Opportunity Zones, as well.

It’s worth underscoring this point: At the urging of a local business owner and public officials, Florida nominated Opportunity Zones in the very same areas targeted by a nationally-recognized neighborhood revitalization nonprofit, which itself vetted the community thoroughly before making it part of the national program. This is… a scandal?

Other Local Options

In spite of abundant evidence that Tract 17 merited consideration, ProPublica’s critique rests on the fact that the West Palm Beach economic development director didn’t include it in his initial early recommendations obtained by the reporters. The tract was, however, included in the list of six tracts that the City of West Palm Beach ultimately submitted for consideration, which were a combination of the three initially recommended by the economic development director and three that formed the core of the PBC study area.

Four out of the six tracts requested by the mayor were eventually chosen by the state. Additionally, Palm Beach county itself submitted recommendations to the state, requesting a total of 31 tracts be nominated as Opportunity Zones. Of those, 13 were eventually nominated, five of which are adjacent to Tract 17. The takeaway here is that many different levels of local government alongside business and nonprofit leaders were making recommendations to the state with substantial overlap among different recommendations. The three tracts submitted by the marina owner were all duplicates, meaning they had been recommended by multiple stakeholders. The state ultimately had to decide which tracts would be nominated under the cap. Those combining merit with diverse support appear to have risen to the top.

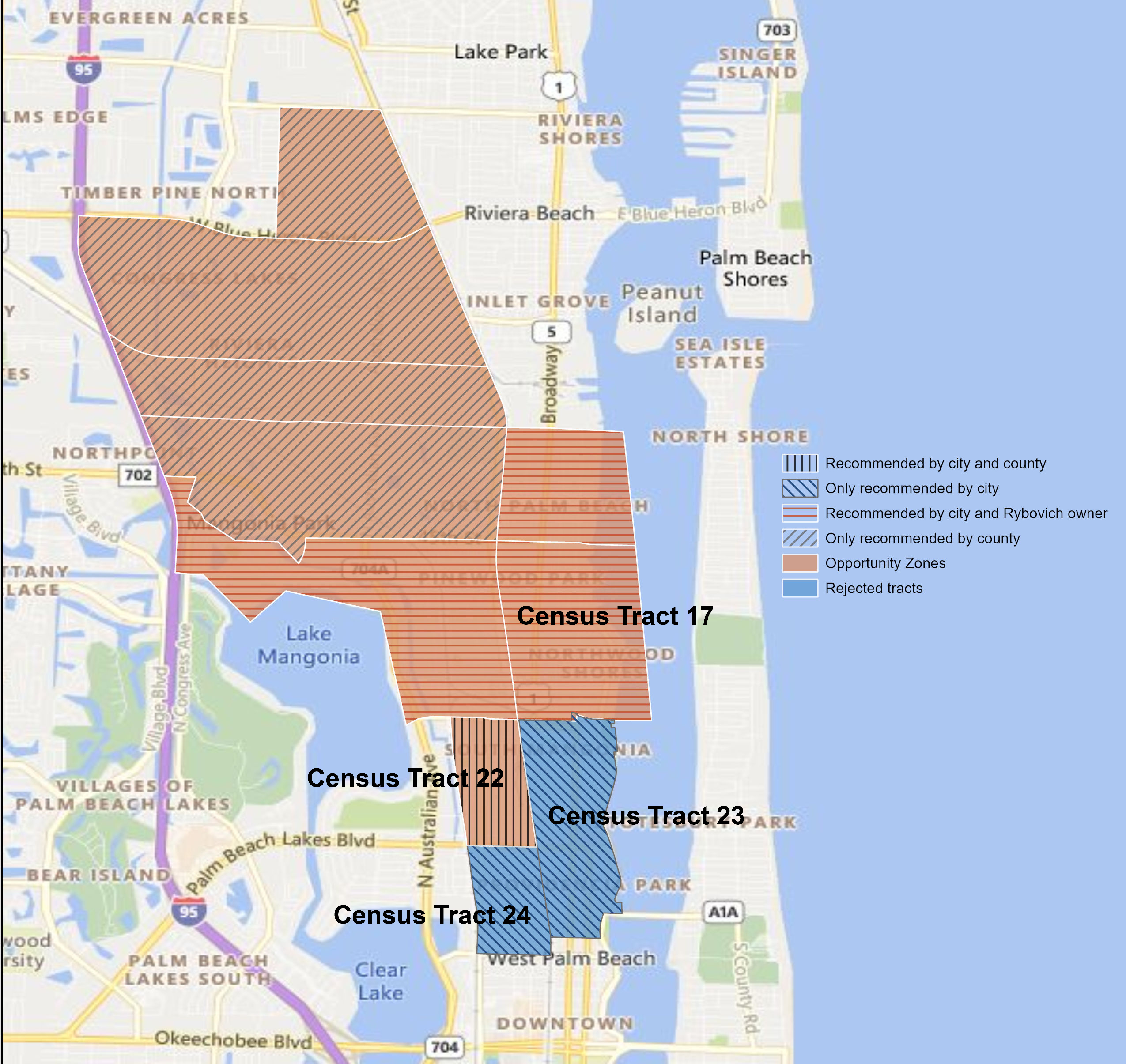

But since so much of the ProPublica narrative rests on the economic development director’s initial three recommendations, it’s worth examining them more closely. Of those three, only one, Census Tract 22, was ultimately selected to be an Opportunity Zone. This tract is clearly the highest need of the three and located the furthest from development pressures. Census Tract 22 has an MFI of $21K and a poverty rate of 41 percent in addition to being 95 percent non-white.

West Palm Beach Opportunity Zones

The two tracts excluded from the state’s final selections were the ones closest to more affluent and developing areas. For example, Census Tract 23 would have arguably been a questionable selection because, while eligible based upon its poverty rate and MFI, it was also a tract flagged by the Urban Institute as at risk of gentrification. This makes sense, since the southern half of the tract overlaps with downtown West Palm Beach (the other tract covering downtown West Palm Beach has an MFI of $106,746). These details were not included in ProPublica’s story, even though the selection of gentrifying tracts — while rare — is often cited as a potential risk of the Opportunity Zones initiative. The second rejected tract, Census Tract 24, does have an especially low MFI of $30,543 and a poverty rate of 30 percent, but it is adjacent to a very high income tract and might also be at risk of development pressures. Tellingly, both of these tracts fall outside the target area for the Purpose Built Communities initiative (and inside the districts identified by community representative quoted above as already seeing development), another detail omitted from the story.

Good faith observers could debate whether the two excluded tracts should have been designated, or whether Tract 17 should have been excluded. But remember: states could only nominate a quarter of their eligible tracts, which by definition means that most of the local recommendations they received would not survive the final cut. Their exclusion is by no means a scandal, nor should one set of local recommendations be viewed as a sacrosanct appraisal of local need. As in all cases, Florida’s Opportunity Zones designations should be evaluated in the broader local context. Here again, the ProPublica piece provides readers little insight into the merits of state’s selections in the surrounding area.

A Corridor of Socioeconomic Need

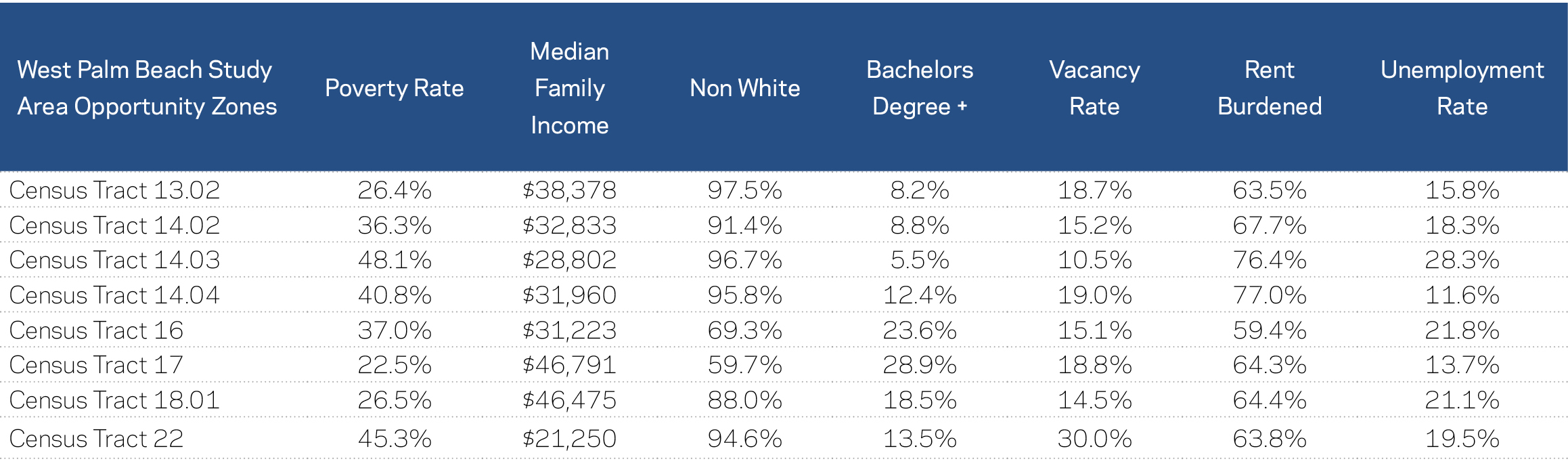

Combining the tracts in West Palm Beach and tracts from nearby Riviera Beach, the state nominated a cluster of eight contiguous Opportunity Zones in the area. Whether evaluated individually or in the aggregate, these areas clearly align with the intent of the policy to encourage investment in underserved areas. In fact, all eight tracts qualify as Opportunity Zones according to both high poverty rates and low median family incomes, when only one of the criteria was required. None of these tracts were flagged by the Urban Institute as at risk of gentrification. Furthermore, in tightly clustering these high-need designations, the state’s approach was consistent with guidance included in the Investing in Opportunity Act, which served as the basis for the Opportunity Zones provision in the 2017 tax reform bill. The bill’s authors encouraged governors to “strive for the creation of qualified opportunity zones that are geographically concentrated and contiguous clusters of population census tracts” as well as areas that “are currently the focus of mutually reinforcing State, local, or private economic development initiatives.”

Why do these things matter? Because a cluster of contiguous low-income areas can improve the chances of attracting a wide array of catalytic local investments that meet an array of local needs, such as building new housing stock, funding the expansion of a local business, and redeveloping a vacant industrial area. And local initiatives like the one by Purpose Built Communities help to ensure the neighborhood’s revitalization is both thoughtfully executed and aligned with the needs of existing residents. The result in West Palm Beach and the surrounding area seems to capture exactly what the legislation’s authors had in mind.

Demographic Data, West Palm Beach Opportunity Zones

Conclusion

ProPublica’s readers are presented with a lurid narrative: the state of Florida chose an undeserving area purely to benefit a connected businessman at the expense of impoverished areas nearby. Like the article’s authors, we were not privy to the deliberations within the governor’s administration, and we have no particular interest in this tract or its circumstances. But even a cursory review of publicly available facts makes clear that this piece did not come close to presenting a fair or complete picture to its readers. Instead, like several other recent stories on Opportunity Zones, it relies heavily on innuendo and association to score its points, while carefully filtering out important context along with any recognition of the complex policy tradeoffs involved in the Opportunity Zones designation process.

The decisions of public officials deserve scrutiny — not sensationalism — especially where tax incentives are involved. Here, scrutiny yields a clear answer: the tract in question qualifies easily on its own merits, aligns with the intent of the policy, and is the target of a pre-existing and carefully-vetted neighborhood revitalization process that could be significantly boosted by the new federal initiative. The presence of a luxury marina in an otherwise impoverished and disinvested area doesn’t invalidate the community being targeted for new investment, nor do recommendations of the marina’s owner made as part of the public input process constitute an abuse of public trust.

Even the article’s headline is misleading: “A Trump Tax Break To Help The Poor Went To a Rich GOP Donor’s Superyacht Marina.” The marina isn’t eligible for tax benefits because it predates the passage of the law. Only new investments that meet specific criteria are eligible for the incentive. And by cleverly focusing the article — headline and all — on the marina, its authors obscure the fact that new investment in Tract 17 would, indeed, be going to an impoverished area with a widely-recognized need for revitalization.

There is no guarantee that any given area will benefit simply because of being made an Opportunity Zone. Long-term success depends upon many factors, including strong local engagement and leadership from civic, business, and public sector stakeholders. But Opportunity Zones is already contributing to Florida communities in the form of affordable housing in Orlando and historic preservation in Jacksonville, as well as flowing through a myriad of other investments throughout the country. Congress can and should do more to improve the incentive, strengthen guardrails, and ensure sound reporting requirements that will allow the policy to be carefully evaluated over its long lifespan.

Unfortunately, ProPublica did little to inform readers of the complex and important factors in play in West Palm Beach. Hopefully our additional digging will help readers come to a more informed opinion.