Delivering Opportunity: A diagnostic and strategy playbook to maximize Indiana’s Opportunity Zones

By Kenan Fikri, Rachel Reilly, and Daniel Newman

I. Executive Summary

Opportunity Zones (OZs) are low-income census tracts in which certain new investments to stimulate economic activity are eligible for special federal tax incentives. They stem from a bipartisan policy enacted in late 2017 intended to bridge the country’s growing geographic divides by rekindling market activity in disinvested neighborhoods. OZs represent one of the most ambitious and potentially far-reaching place-based economic policies in a generation.

Yet, given the potential scale of the opportunity, engagement across the state and particularly among the investor community could be significantly greater. To fully maximize what OZs can do for Indiana, the state must focus on addressing the two binding constraints on further expansion and maturation of the OZ marketplace identified through this research: raising more local capital for local investing and increasing the capacity of stakeholders to understand and deploy this new financing tool.

Mapping Opportunity Zones

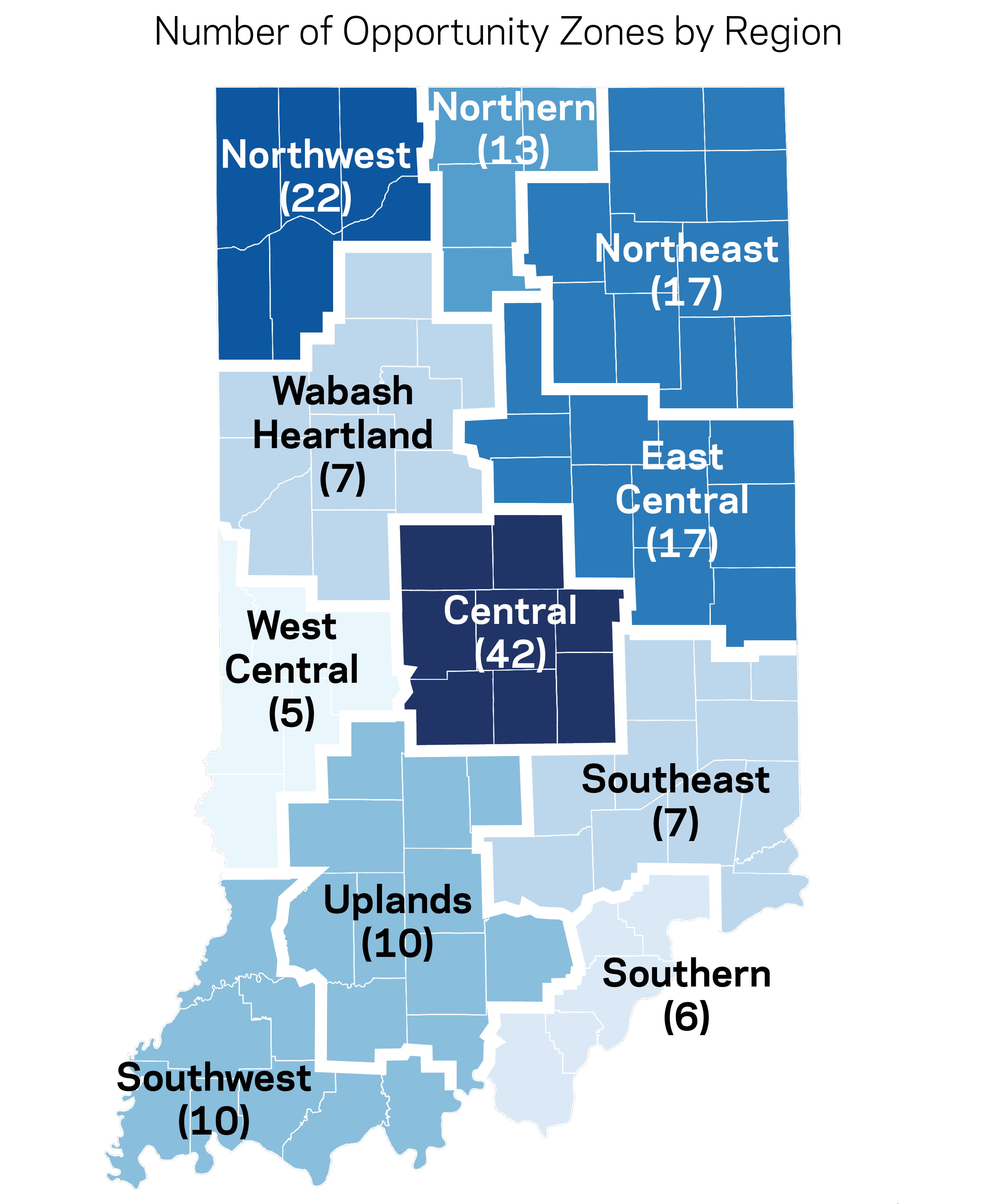

Indiana is home to 156 designated OZs distributed throughout the state. More than half a million people, or 8 percent of the state’s population, live in them.

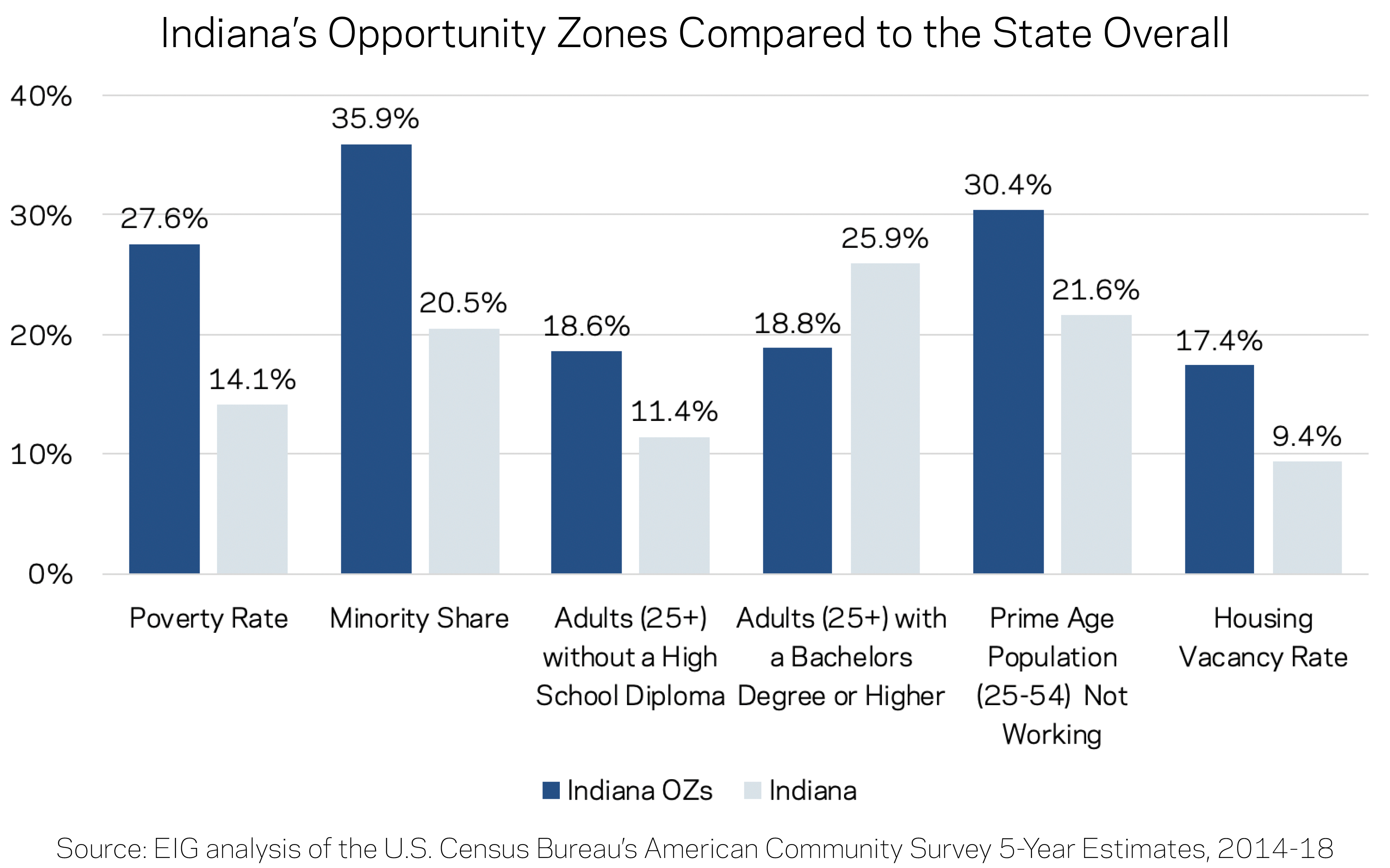

Even before COVID-19 struck, OZ communities were struggling with poverty rates nearly twice the statewide level, far more adults out of work, elevated housing vacancy rates, and lagging educational attainment. OZs also provide a window into economic and geographic inequalities across race that exist at the national level and in Indiana: 36 percent of OZ residents in the state are minorities, compared to 20.5 percent of Indiana’s total population.

The public health crisis unleashed by the novel coronavirus has exposed deep inequities in physical well-being that correspond with those in economic well-being, too. The average life expectancy for the state’s OZs is 73.3 years, compared to 78.6 nationwide.

Children in particular can suffer long-term consequences from living in socially and economically left-behind communities. Nine out of 10 OZ tracts (and 105,500 children living in them) are in areas with low or very low child opportunity scores, meaning they often lack quality early childhood education and schools, safe housing, access to healthy food, parks and playgrounds, and clean air.

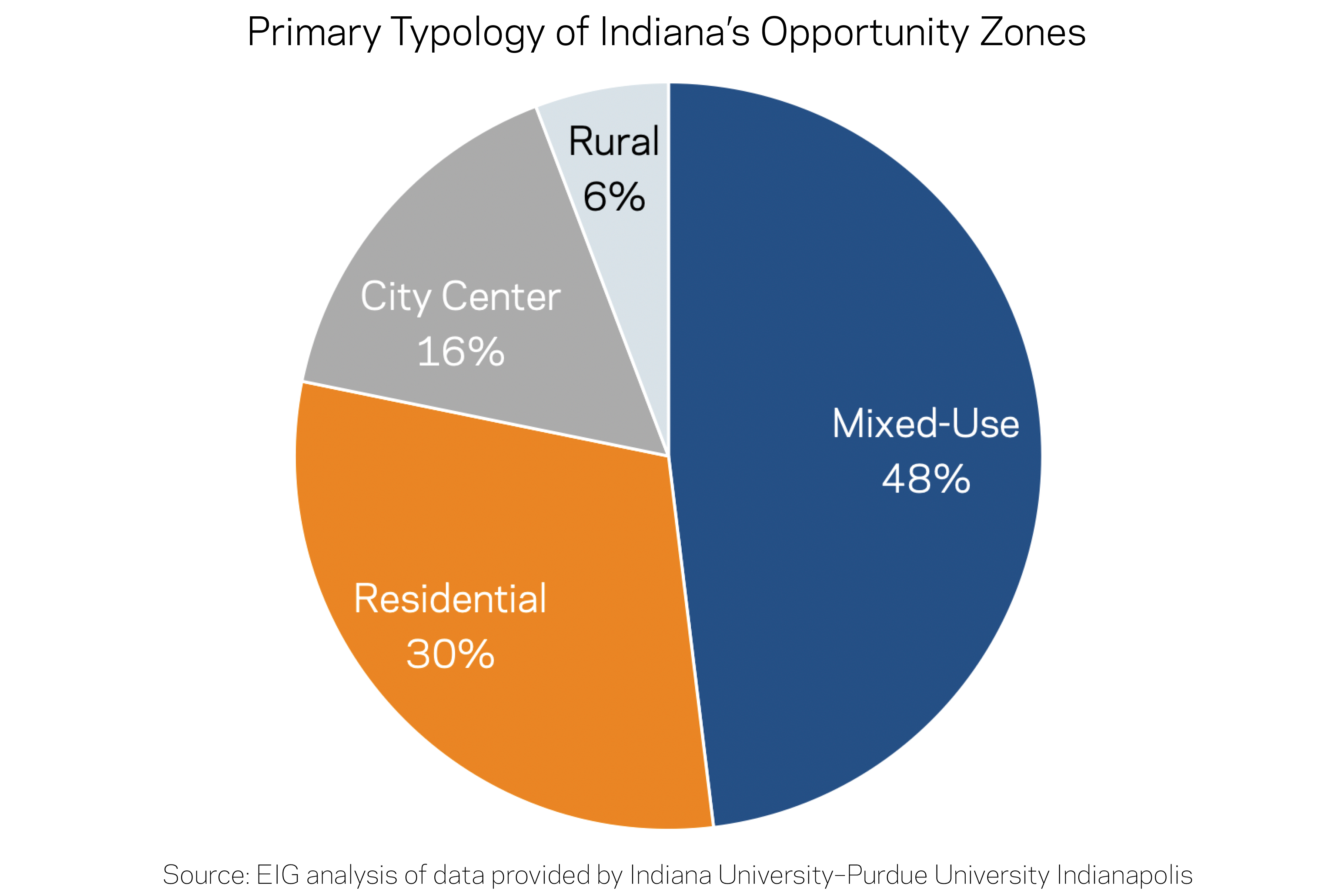

To help ground the analysis and recommendations presented here, we created primary and secondary typologies for the state’s OZs that can inform strategies or point towards investment opportunities.

The four primary typology categories include: mixed-use, city center, residential, or rural based on the local land use composition. Nearly half of all OZs in the state can be considered mixed-use, with diverse investment opportunities.

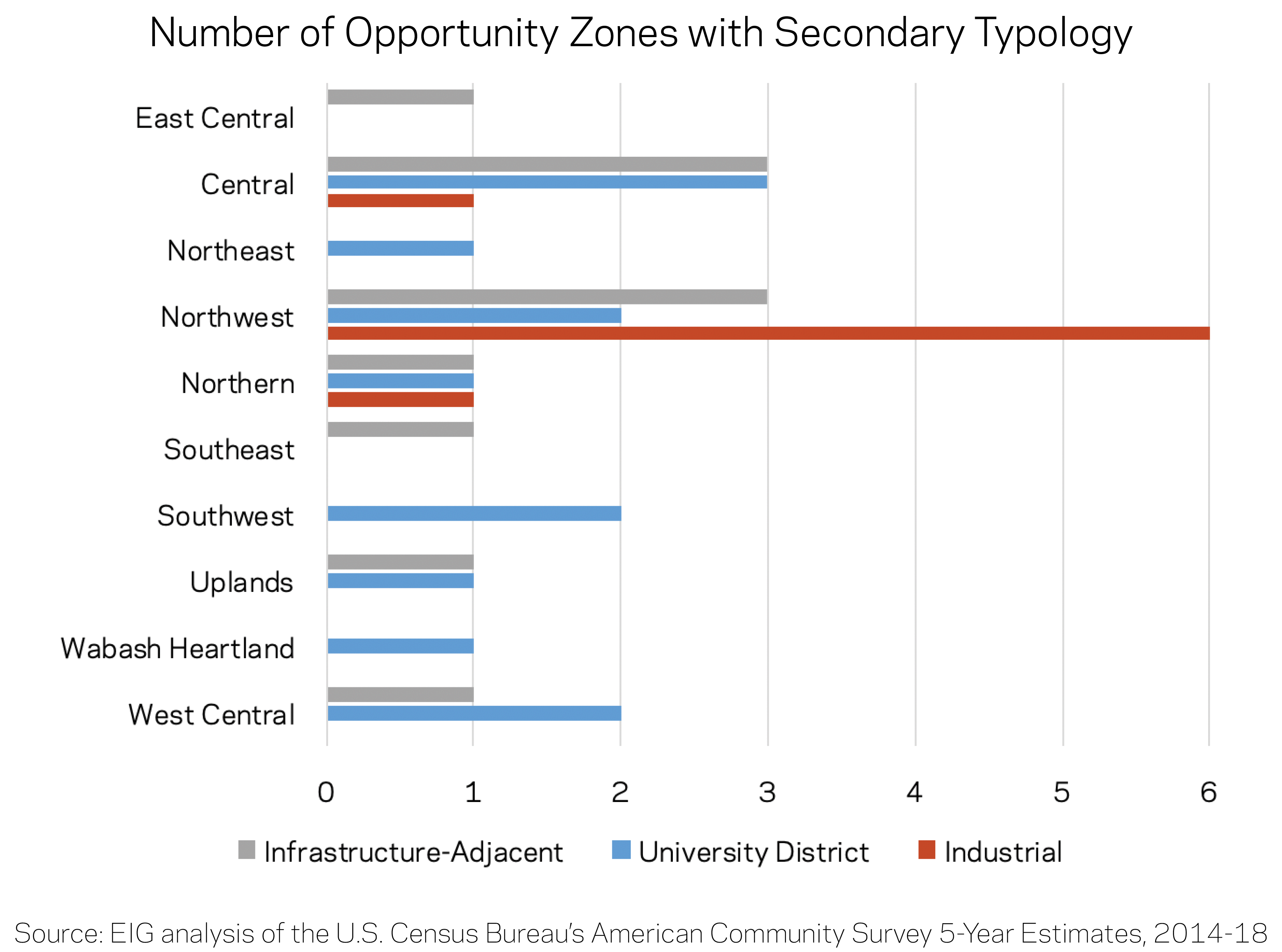

Secondary typologies are meant to differentiate beyond predominant land uses to capture areas that may present special investment opportunities or warrant specialized development strategies. They include:

- University district: Tracts that either contain or are immediately adjacent to major colleges and universities.

- Industrial: Tracts that contain sizeable areas zoned for industrial use, large warehouses, and/or significant pieces of manufacturing infrastructure.

- Infrastructure-adjacent: Tracts that are near airports, railyards, or other significant transportation infrastructure, but tend to be zoned for relatively little industrial activity.

Needs and Opportunities

Four key issue areas emerged from numerous conversations with local stakeholders across Indiana as realms in which OZs are primely positioned to help the state further its goals. OZs can contribute directly to the state’s efforts to:

- Build a dynamic and resilient economy: Entrepreneurs are a critical feedstock for the economy, as a steady stream of new companies maintains high levels of productivity, keeps markets competitive, and helps economies adapt to change. Yet Indiana ranks last nationally in terms of its share of jobs in new companies, and it ranks third for the share of all of its jobs in very old firms. That leaves the state’s economy at risk from shocks and economic change. Indiana retains the building blocks of a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem in and around its OZs. Thirteen of the state’s OZs are part of university districts, and at least seven business incubators and accelerators are located in OZs. Eight of the state’s 20 Certified Tech Parks are also located in OZs, and another six in close proximity to one. Tech in Indianapolis and Electric Works in Fort Wayne, two of the state’s most significant efforts to combine innovation and entrepreneurship with physical redevelopment, are both located in OZs. OZ capital can add to the mix in multiple ways. An investor could help boost a new startup that is commercializing technology from one of Indiana’s leading universities by taking a venture capital-style equity stake in the business, for example. Or OZ capital can be deployed to finance the build-outs of innovation districts, providing startups with office space, or via direct investments into incubating growth companies. OZ financing can also aid in the expansion of existing businesses. It can be used to acquire new capital equipment, to build a new facility, or to hire and grow when certain conditions are met.

- Create livable communities: Vibrant, inviting communities are essential assets in the competition for talent and human capital. OZs can help enhance and create livable communities in a number of ways. For example, the incentive can be leveraged in large-scale master-planned placemaking efforts as one financing tool among many. OZs can dovetail into more organic placemaking efforts on much smaller scales, as well. Across the country, OZ capital is being used to revitalize Main Street storefronts, community spaces, and living. It is often being deployed for historic preservation or adaptive reuse. In other circumstances, OZs can be an ally in reducing vacancies, removing blight, and remediating brownfields as well. Here the need in some regions is acute. The housing vacancy rate in the average Indiana Opportunity Zone is 17 percent, compared to 11 percent statewide and 8 percent nationally. As a state with a long industrial history, Indiana’s OZs also contain nearly 500 brownfield sites—disutilized and contaminated parcels—that weigh heavily on their surrounding communities. Helpfully, federal regulations finalized in late 2019 enumerated several specific leverage points for local governments and public sector entities to use OZs to address vacancy and blight.

- Improve resident health: Livable communities that encourage walking and outdoor recreation are healthy communities, making this strategic priority closely related to the prior one. The quality of the built environment, open space, and safety all matter for improving baseline health in a community. Strong communities also foster better mental health—an urgent priority given that, across Indiana’s urban OZs, nearly one in every five residents reported poor mental health even before the pandemic hit. Access to fresh, healthy foods is another cornerstone of a healthy community that is missing from too many OZs. Statewide, 53 OZs are considered food deserts by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This means that residents of one-third of Indiana’s OZs do not have access to a full-service grocery store within one mile in an urban area or 10 miles in a rural one. In the Central region, one-quarter of OZs are food deserts and in Northwest Indiana, fully half are.

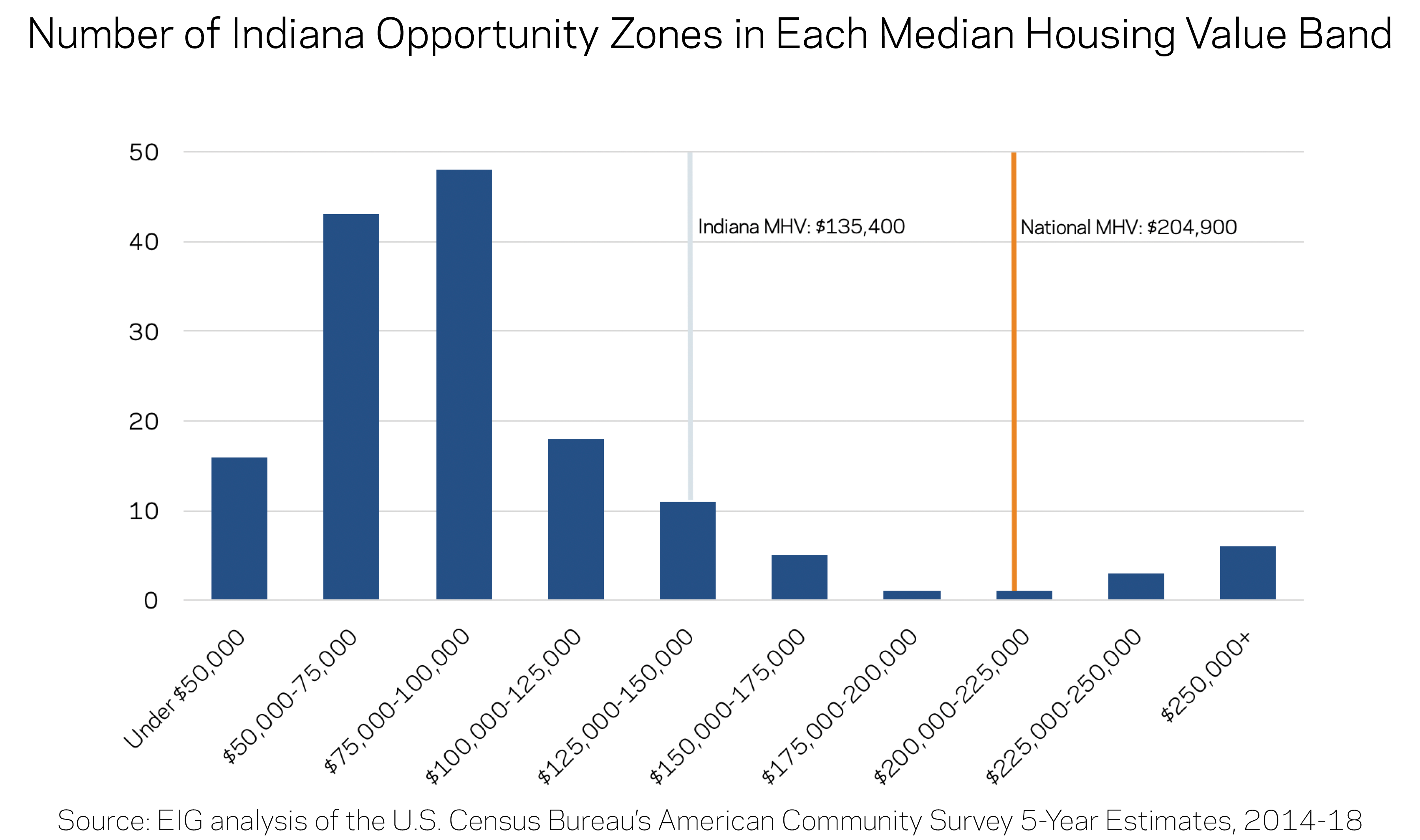

- Provide quality, affordable housing: Housing is the cornerstone of individual economic well-being and critically important for economic development and talent attraction. Across Indiana’s OZs, 51 percent of renting households are rent-burdened on average, seven percentage points higher than the rest of the state. On average, only 9 percent of housing structures in OZs have been built since 2000 compared to 16 percent statewide. The lack of newer structures contributes to the fact that fully two-thirds of the housing stock in Indiana’s OZs was built prior to 1970. That statistic, combined with distressed home values, implies that a housing quality problem holds back the renewal of many of the state’s OZs.

Strategies for delivering investment and impact

Indiana stepped out of the gates and quickly accumulated some of the most exciting OZ initiatives and developments in the country over the course of the policy’s first two years.

These examples make clear that many members of Indiana’s civic and business communities have risen to the entrepreneurial challenge presented by OZs and are determined to make this new economic development tool work for their communities. Despite the early promise, however, the investment map remains a patchwork. Too little locally-committed capital has been raised, especially relative to neighboring Ohio. Many potential stakeholders still know too little about this new policy tool to fully imagine how, where, and to what ends it can be applied. Others only know OZs as another tax incentive for real estate, unaware how late-breaking regulations ease the path for OZs to finance startups and economic development more broadly. Meanwhile, the unfamiliar market-based structure of OZs makes it hard for many key players in the traditional community development space to identify the best leverage points for shaping the market towards social impact.

To overcome these binding constraints on the market’s growth and maximize the potential of the new federal OZ incentives for Indiana communities, the following strategies should be considered to unlock more capital and strengthen local capacity:

- Establish a statewide OZ coordinator: The most community-aligned engagement from OZ investors is taking root in places where a person or organization is fully dedicated to cultivating a pipeline of high-impact deals and investor relationships. Places such as Alabama, Colorado, and Baltimore, MD, have at least one full-time employee serving as an OZ coordinator for the city or state, and they have created a long-term framework for directing resources to OZs and measuring impact. Philanthropy often supports these positions.

- Create a centralized online directory of essential OZ information: One of the most powerful ways to foster an investable environment is to facilitate the flow of relevant information between state and local governments and OZ stakeholders. States such as Maryland, California, and New Jersey have established digital “one-stop shops” or centralized directories for OZ investors, communities, and potential investment recipients (startups, growth businesses, or project sponsors) containing information about the incentive, who may qualify for what, and complementary federal, state, and local resources. Many clearly articulate the state’s own priorities for OZs, and some even contain databases of vacant and underutilized properties (some publicly-owned, some private) that are primely positioned for redevelopment.

- Enhance and align public resources to strengthen OZ communities and shape the market. As state and local governments think through their own financial and programmatic commitment to OZs, they should review their policy tools in the following four realms and consider if and how they wish to align them with OZs in order to nudge the young marketplace toward particular ends:

- Programs and incentives to support new and growing businesses

- Startup accelerators, capacity building, and workforce training programs

- Credit facilities

- Programs or grants to monitor and measure impact

- Activate residents, businesses, and community stakeholders. As demonstrated in Brookville, engaging the local investor base can be a powerful way to spark new energy and economic activity locally and unlock OZ investment for projects and businesses that strengthen the community. Beyond individuals and families, major employers, philanthropic institutions and similarly aligned community stakeholders with vested interests in the quality and livability of OZs can be activated in various ways, including via additional investment carrots, the creation of place-based Opportunity Funds, public-private partnerships, and tailored strategies to reach anchor institutions and philanthropy.

Looking ahead

Across the country, the places seeing the most robust and aligned investment activity in their OZs are ones that have jumped right in to facilitate a new local investment ecosystem into existence. Early returns show the importance of tending to all sides of the marketplace: building an investor base, cultivating a deal pipeline, engaging residents and communities, educating businesses eligible for investment, and building the capacity of local governments and liaisons.

There was no shortage of economic and community development priorities that needed financing before the pandemic. Need has only grown more acute since—especially in low-income communities. OZs add a potentially powerful new financing tool to the mix.

The GPS Project gives Hoosiers a hook to provide their OZ ambitions strategic focus. This long-term economic and community development tool can help finance the next generation of businesses that will secure the state’s prosperity. OZ capital can be harnessed to reinvigorate Main Streets and build vibrant, inclusive places that make Indiana a magnet for talent. And by being a market-based tool that integrates seamlessly into local economies, OZs can be a catalyst for building wealth and restoring economic opportunity in parts of the state where both are sorely lacking.