John W Lettieri, EIG’s cofounder and senior director for policy and strategy, recently testified before the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship at its hearing on the state of American entrepreneurship. In his testimony, Lettieri spoke of the decline of U.S. entrepreneurship as the central feature of an overall decline in economic dynamism — one that will have profound consequences if not addressed. He also highlighted the bipartisan Investing in Opportunity Act as an innovative solution to the converging challenges of declining new business formation, growing geographic disparities, and the need for greater investment in America’s economically distressed communities.

Lettieri’s full written testimony is below.

America Without Entrepreneurs: The Consequences of Dwindling Startup Activity

Testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship

June 29, 2016

Introduction

Chairman Vitter, Ranking Member Shaheen, and members of the Committee: thank you for the opportunity to testify today.

My name is John Lettieri. I am the co-founder and senior director for policy and strategy at the Economic Innovation Group (EIG). EIG is a bipartisan economic research and advocacy organization dedicated to fostering a more dynamic and entrepreneurial American economy, so we are particularly grateful for the Committee’s leadership in drawing attention to the challenges facing America’s entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurship and the American Identity

Nothing is more integral to our nation’s cultural or economic identity than entrepreneurship. Dating back to our founding, the United States has been a nation of entrepreneurs and pioneers ready to challenge the incumbents and disrupt the established order.

However, as a nation we now face many of the same challenges that cripple and calcify once-innovative businesses: growing risk aversion, slowing growth rates, and broader transformations that threaten our market position.

In short, the decline of U.S. economic dynamism is the fundamental challenge of our time, and the decline of entrepreneurship is its central and most problematic feature.

The decline of U.S. economic dynamism is the fundamental challenge of our time, and the decline of entrepreneurship is its central and most problematic feature.

The Challenge of Declining Dynamism

This decline has far-reaching implications. Americans are far less likely to start a company today than they were 30 years ago — far less likely to see starting a business as a pathway to realizing the American Dream. This corresponds with a series of other interrelated trends that point to a less dynamic future.

Americans today are also less likely to move to new areas of the country. They are less likely to switch jobs. The average company is rapidly getting older. Industry sectors are seeing widespread consolidation. Historically, the churn caused by a steady influx of new businesses has acted as a kind of shock absorber for our economy. This is no longer the case. Even as the global economy has undergone massive transformations driven by technology and globalization, the U.S. economy is rapidly becoming less flexible, less able to adapt, and less efficient at allocating resources — including its most precious resource: human capital.

These changes are felt most acutely in those parts of the country that have fallen behind and are struggling to replace lost industries and millions of middle class jobs. As a result, a rising tide of geographic inequality separates millions of Americans from the economic gains of the national recovery, as fewer areas than ever are carrying the bulk of overall U.S. economic growth.

The consequences are dire. A less entrepreneurial America is one with increasingly limited opportunities to realize the American Dream.

A less entrepreneurial America is one with increasingly limited opportunities to realize the American Dream.

Today’s policymakers will decide if our economic future belongs to the incumbents, or if we will instead renew the entrepreneurial spirit that has fueled American dynamism from the very beginning.

Inherent Strengths

In spite of the challenges, the United States retains a unique mix of advantages that point to its potential for an entrepreneurial comeback. We are home to the world’s leading university and research system that has long served as a cradle for game-changing innovations. We own the majority share of global angel and venture capital. We are a magnet for the world’s top talent. We have a historic tolerance for entrepreneurial risk-taking. And the United States remains home to the world’s most dynamic clusters of innovation. The right policy decisions and the right leadership can help us rediscover the broader economic dynamism that defined our nation throughout the 20th century.

The right policy decisions and the right leadership can help us rediscover the broader economic dynamism that defined our nation throughout the 20th century.

Trends

While there are many ways to assess the state of U.S. entrepreneurship, I would like to highlight the six trends that I believe best encapsulate the magnitude of current challenges:

- The rate at which the U.S. economy generates new firms is in long-term decline;

- New business formation suffered an unprecedented collapse following the Great Recession;

- The geography of startup activity has become highly concentrated;

- The economy is increasingly dominated by older incumbent firms;

- Rates of entrepreneurship are declining with each generation; and

- High-potential startups are less likely than ever to succeed.

1. The new business formation rate is in long-term decline.

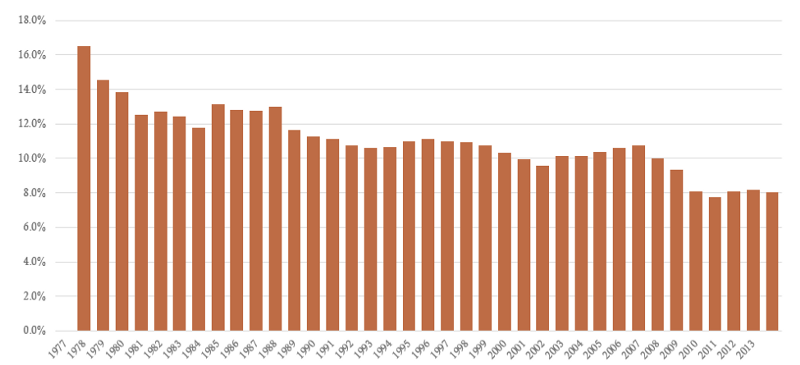

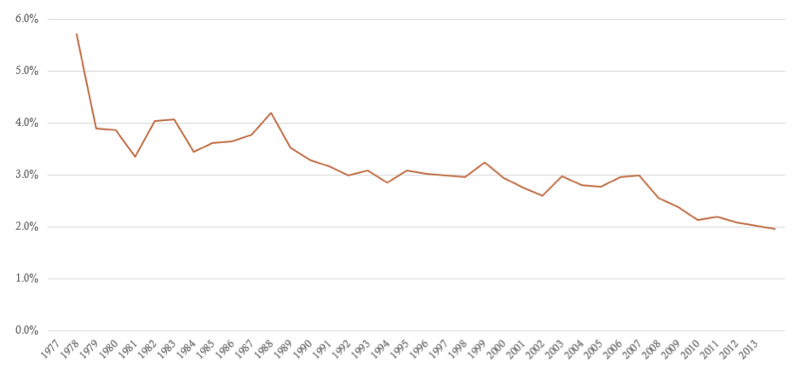

The U.S. economy has been steadily getting less entrepreneurial for decades. From 1977 to 2013, startups as a share of all firms fell from 16.5 percent to 8.0 percent, while the share of the workforce employed in new firms fell from 5.7 percent to 2.0 percent. The decline is pervasive across states and across sectors, including high tech.

2. New business formation suffered an unprecedented collapse following the Great Recession.

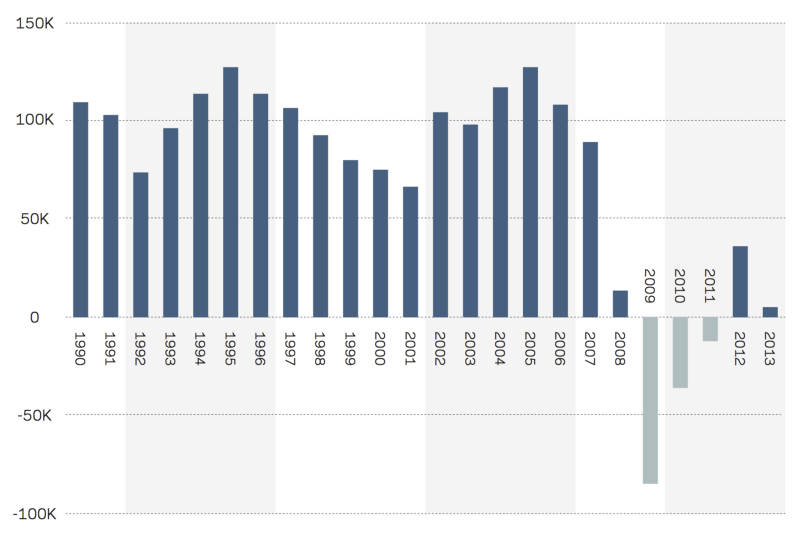

EIG’s recent report, “The New Map of Economic Growth and Recovery,” found a startling collapse in new business formation, starting with the Great Recession. Beginning in 2009, the total number of firms in the economy actually fell for three consecutive years. This is unprecedented; even during prior recessions the economy produced tens of thousands of new companies on net. In 2013, the most recent year for which data is available, the number of firms in the U.S. economy increased by fewer than 6,000 — a paltry sum compared to the average of over 101,000 new firms added annually between 2000 to 2007.

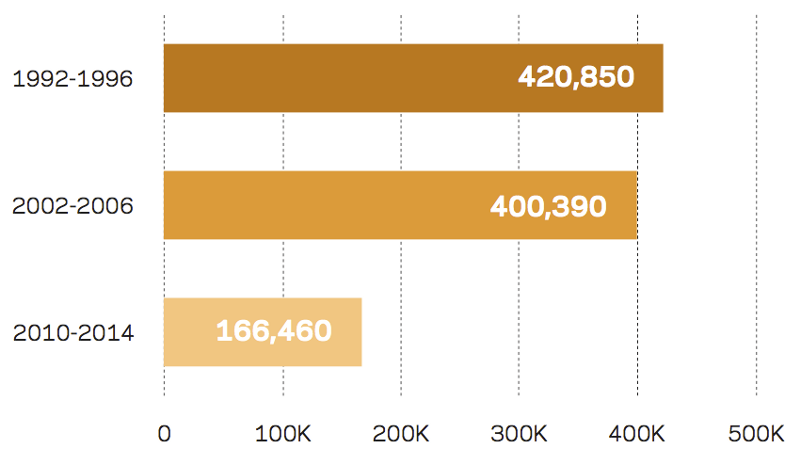

The comparison to previous recovery periods is particularly stark. In each of the five year periods following both the 1991 and 2001 recessions, the U.S. economy added over 400,000 net new business establishments — physical places of business that serve as tangible signs of recovery for their communities. But from 2010 to 2014, the net increase was an anemic 166,500. Had the number of establishments increased at the same rate as in the 1990s, the United States would have seen nearly 500,000 new establishments open in communities across the country. The Great Recession has left a lost generation of new enterprise in its wake, the effects of which will be felt for years to come.

3. The geography of startup activity has become highly concentrated.

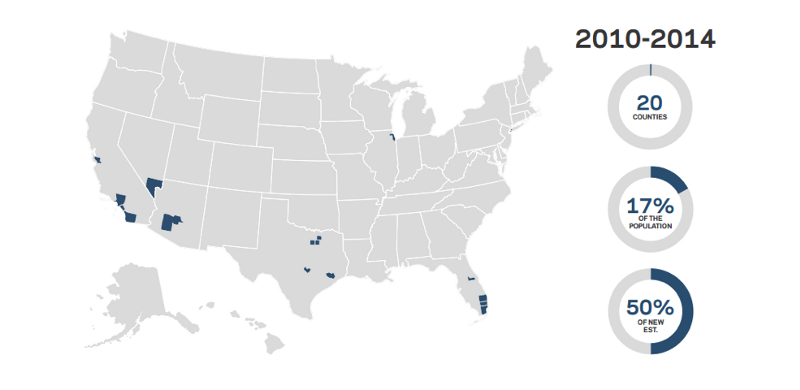

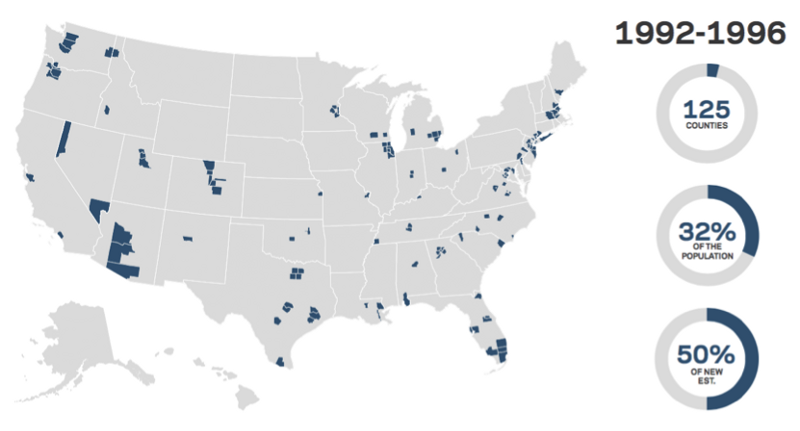

EIG’s “New Map” report shows that the geography of new business formation was highly concentrated in a few elite hubs following the Great Recession. Half of the entire net rise in business establishments in the United States from 2010 to 2014 was contained in only 20 counties — despite the fact they were home to only 17 percent of the nation’s population. Furthermore, 17 of these 20 super-performing counties were found in just four states: California, Florida, New York, and Texas.

This pattern stands in stark contrast to past recoveries, which saw much more broadly dispersed new business growth. For example, from 1992 to 1996, more than six times as many counties combined to generate the same proportion of the nation’s cohort of new businesses: 125 counties dispersed throughout the country and housing 32 percent of the population.

This extreme concentration of new business activity signals the difficulty would-be entrepreneurs experience in incubating and growing new businesses outside of the elite hubs where capital, networks, and other assets are abundant. Entrepreneurs are clustering in high-cost, high-density areas of the country — areas that present high barriers to entry for lower-income Americans. This feeds a cycle that further segregates entrepreneurs and the businesses they start in select areas of the country.

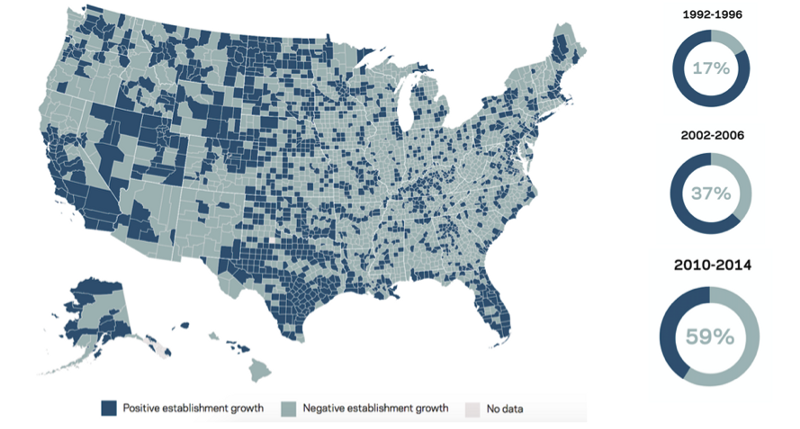

Meanwhile, the number of counties that lost business establishments during the national recovery has more than tripled since the 1990s. During the five years of nominal economic recovery from 2010 to 2014, fully 59 percent of counties saw more businesses close than open. In contrast, between 1992 and 1996, only 17 percent of counties suffered from a net loss in business establishments.

The headwinds are particularly severe for small town and rural entrepreneurship. Consider that small counties (those with less than 100,000 in population) generated the highest rates of new business formation and nearly one-third of the net increase in U.S. businesses from 1992 to 1996. Since then, they have suffered an astonishing shift in fortune; on average, these counties saw net negative establishment growth in the recent national recovery period.

4. The economy is becoming dominated by older incumbent firms.

The declining share of startups in the economy has occurred alongside an aging of the private sector, with workers increasingly likely to work at old and large firms. This matters because, as Robert Litan and Ian Hathaway note in their 2014 paper, older firms are less dynamic than younger ones, and an economy dominated by older firms is one that may be less likely to achieve consistently strong rates of growth. Between 1993 and 2013, the share of firms in the economy aged 16 and over increased by 12 percentage points, while the share of the workforce employed in such firms rose from 62 percent to 73 percent over the same period. In 2006, the country passed a landmark: for the first time in history, a majority of the workforce was employed in firms with at least 500 workers. That number has continued to rise ever since.

5. Millennials are on track to be the least entrepreneurial generation in recent history.

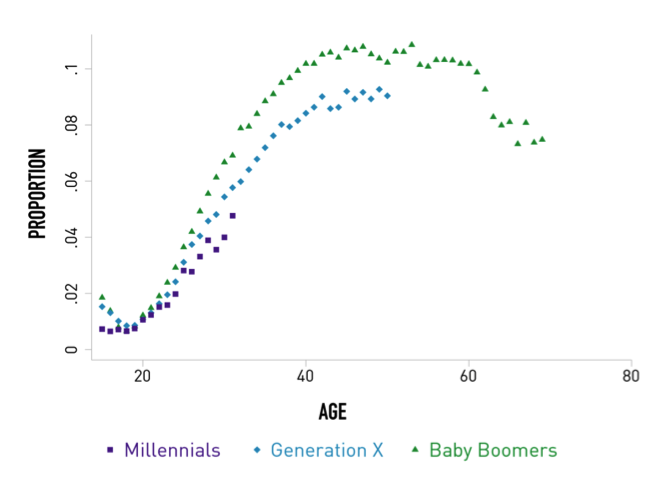

These macro-trends have a generational dimension as well. According to a new Small Business Administration report, Millennials are the least entrepreneurial generation in recent history. At age 30, less than four percent of Millennials reported self-employment as their primary job, compared to 5.4 percent at that age for Generation Xers and 6.7 percent for Baby Boomers.

Similarly, a Wall Street Journal analysis of Federal Reserve data found that the share of households headed by someone under 30 with a stake in or ownership of a private business has fallen from over 10 percent in 1989 to 3.6 percent in 2013.

Furthermore, research by the Kauffman Foundation shows that young people were responsible for half the share of startup launches in 2014 as they were in 1996. Although these are clearly signs of a generational decline, it is important to remember that Millennials have yet to hit 40, the peak age for launching a startup.

6. High-potential startups may be less likely than ever to succeed.

Recent research from MIT adds another dimension to the picture: even today’s highest quality startups may be having more difficulty scaling to high growth than their predecessors.

High-growth startups, while always an extreme minority of the total pool of new businesses, are important because of their outsized role in job creation and disruptive innovation. Using a novel methodology, the MIT researchers found that a high-potential startup founded in 1996 was four times more likely to experience a growth event (e.g., IPO or acquisition) within six years than a startup founded in 2005. Even as the Great Recession fades, there is reason to worry that the country’s entrepreneurial ecosystem remains far less conducive to growth than it was in the 1990s. In other words, we’re getting fewer Amazons and Apples for every Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs today, which has widespread implications for future U.S. job creation, innovation, and productivity gains.

Consequences of Declining Entrepreneurship

What are the consequences? Many of our biggest concerns today are not isolated conditions but in fact symptoms of this deeper malaise in entrepreneurship. Let’s explore some of the biggest consequences of the startup slowdown in turn:

Less innovation

New businesses are disproportionately likely to introduce radical new product and process innovations that disrupt industries and established interests. As new entrants into the market, startups have the ability to pursue new ideas and seize upon new knowledge in a way that older, more risk-averse firms avoid. Startups also form a critical link in the nation’s more formal innovation ecosystem. Many are born from the commercialization of technologies developed in universities — the primary channel through which the federal government funds innovation. Without vibrant entrepreneurship, much of this federal investment will never realize its market potential.

Less competition

Fewer new firms entering the market has already allowed for increasing consolidation within industries, lower rates of corporate investment, and increasing returns to incumbency. A recent evaluation by The Economist quantifies the increasing market concentration across today’s economy. Their analysis found that two-thirds of all industry sectors became more concentrated between 1997 and 2012, with the top four firms in each sector capturing an increasing share of total revenue. Without healthy competition, incumbents have less of a reason to innovate and more ability to raise prices. In a less competitive economy, the fruits of economic growth that should be returned to workers and consumers instead become rents enjoyed by incumbents.

In a less competitive economy, the fruits of economic growth that should be returned to workers and consumers instead become rents enjoyed by incumbents.

Lower productivity

GDP growth has been stuck near 2.0 percent since 2005, and the rate of productivity growth is projected to turn negative for the first time in more than three decades in 2016. In the 85 years the Bureau of Economic Analysis has been collecting data, the present is the only 10 year stretch in which annual GDP growth has never hit 3 percent.

The fall-off in new business formation is an under-explored potential explanation for why the economy is producing less than it should for each hour worked — and why living standards are stagnating as a result. Entrepreneurs are the driving force behind the process of creative destruction that keeps the economy efficient, productive, and advancing. As new businesses commercialize innovations and their business models disrupt calcified industries and light fires under bloated firms, startups pressure the economy to allocate its resources to their most valuable and efficient use.

Greater inequality

As mentioned above, without robust competition profits will quickly turn into rents and these rents will fuel inequality. Recent work from Jason Furman and Peter Orszag documents how firms have enjoyed rapidly-rising returns on capital in industries that have become more concentrated. They show that this intra-industry inequality has been a major contributor to rising income inequality among workers. In other words, the weakening of competition, which can be directly tied to the decline in startups (challengers), is responsible for a significant portion of the increase in inequality in the United States. Economic theory suggests that new companies should enter the market to compete away these super-normal profits, but that is not happening.

At the same time, there are rising concerns that entrepreneurship is becoming the province of the wealthy. The Center for American Progress has found that the wealth gap between the entrepreneurial class and the middle class is expanding. As entrepreneurship grows farther out of reach for middle income Americans, it loses its promise as a path to opportunity; instead it becomes a luxury good. A recent Harvard Business School survey of alumni expresses the concern: “entrepreneurship might become a source of prosperity but not shared prosperity in the United States.”

Fewer job opportunities

New firm starts are responsible for the vast majority of the economy’s net job growth in any given year and about one-fifth of gross job growth. A decline in new firm starts translates into fewer job opportunities and lower rates of turnover in the labor market.

The negative effects of this reduced dynamism hit disadvantaged populations hardest. The demand for labor from new and growing firms (incumbent firms shed jobs on net in most years) is especially important for young, less educated, and marginally attached workers who can only get ahead and start to establish a career trajectory when labor markets are tight. Similarly, new firms’ demand for labor puts pressure on existing firms to raise wages. Wages have stagnated alongside the decline in entrepreneurship and especially during the recovery, and young people have struggled to find their footing in the recovery’s weak labor market; the lack of young firms partially explains why.

Widening geographic disparities

The uneven geography of the collapse in new business formation implies that large swathes of the country will soon contend with the implications of a missing generation of new businesses — a missing generation of employment providers, investors, and taxpayers. The few remaining startup hubs, for their part, will reap disproportionate rewards as lone oases of capital and innovation. Tellingly, 10 percent of all new worker earnings from 2010 to 2014 accrued to the 2.6 percent of the workforce that lives in California’s Bay Area, even though that nine-county region claimed only 3.8 percent of the nation’s job growth. Such disparities will stress our political system and our nation’s social fabric more and more in the years ahead.

The uneven geography of the collapse in new business formation implies that large swathes of the country will soon contend with the implications of a missing generation of new businesses — a missing generation of employment providers, investors, and taxpayers.

EIG’s own Distressed Communities Index found that net business establishment closures were strongly correlated with other measures of economic distress, such as poverty and worklessness. The number of business establishments is declining fastest in the places with the highest levels of economic distress. Without rebuilding the base of taxpayers and employment providers, communities will fall into disrepair and despair. The crisis in Flint, MI, demonstrates very clearly the human cost of accepting vanishing business activity from certain communities as inevitable.

In past eras, high rates of geographic mobility helped to balance divergences in economic well-being across regions, as people readily moved to places with better economic opportunities, high rates of entrepreneurship, and robust growth. Rates of moving across states have fallen gradually since the 1960s and then rapidly since the mid-2000s; for 2014 to 2015, only 1.6 percent of the population moved between states. The most disadvantaged populations, for their part, are least likely to be able to pack up and move to economic opportunity in expensive coastal cities — and entrepreneurship is clearly retreating to prime locales. Derek Thompson of The Atlantic has written on the compelling links between housing policy, land use regulations, and the decline in labor mobility. If only the wealthy can afford to move to opportunity-rich locales, the country’s most dynamic clusters cannot serve as engines of upward mobility. If entrepreneurship is to fulfill its traditional role as a generator of prosperity, people must be able to not only choose it for themselves but also access the employment opportunities it provides.

Causes of the Startup Slowdown

No matter how you look at it, U.S. entrepreneurship faces a crisis — one with far-reaching consequences. But why?

There are many fundamental questions still unanswered. The decline is so stark and so relentless that it can’t be attributed to any single factor. Instead, it is likely that a multitude of forces have conspired to sap the country of its entrepreneurial energy. Here I’d like to discuss some of the most apparent potential causes.

Access to Capital

The most compelling partial explanations for the widespread collapse in new business formation post-recession involve access to capital. This is perhaps not surprising, given that the recession was precipitated by a financial crisis, which hit many of the primary sources of individuals’ startup capital the hardest.

- Lending. Almost seven years into the recovery, total small business lending remains down by a quarter relative to before the financial crisis. Community banks, a key source of capital for new and small enterprises, are vanishing: one out of every four has disappeared since 2008. Some of this reduction is due to consolidation within the banking industry; larger, national banks have a lower propensity to make local small business loans.

- Housing Wealth. In addition to personal savings, housing wealth serves as a traditional source of capital for entrepreneurs. Such wealth evaporated with the bursting of the housing bubble and has been slow to come back in many regions. Forthcoming research from Steven Davis and John Haltiwanger into the regional relationship between housing market conditions and startups finds that fluctuations in home equity values have a pronounced effect on the local rate of new business activity. This occurs via two channels: the individual wealth effect and the proceeds from mortgage lending that banks channel into business loans.

- Concentrated Risk Capital. Contributing to the geographically uneven nature of the collapse in business formation is the spiky geography of risk capital. Venture capital, for example, remains highly sequestered on the coasts. The top three states — California, Massachusetts, and New York — received 78 percent of all investments in 2015, according to the National Venture Capital Association. Meanwhile, half of America’s 366 metro areas failed to capture even a single dollar of new venture investment. Recent research further underscores the dominance of a select few cities in the economy’s venture landscape. Consider the following juxtaposition: less than four percent of U.S. zip codes receive any venture capital, but the top ten individual zip codes capture over a fifth of the national total. This extreme concentration signals that, for the vast majority of American communities, this important source of entrepreneurial funding is completely inaccessible.

Although venture capital funds only a small segment of the entrepreneurial population, it has an outsized economic impact. For one, its footprint coincides almost exactly with geographic concentrations of the high-potential startups, making it inordinately important for building new industry bases in regional economies. A recent study out of Stanford University found that venture-backed companies account for 43 percent of U.S. public companies founded since 1979 and 57 percent of that market capitalization. What is more, they conduct 82 percent of public companies’ R&D.

Regulatory Complexity

It’s no secret that small business owners face a daunting task in navigating our regulatory and tax system. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business report, the United States ranks 49th out of 189 countries for the ease of starting a business, an abysmally low performance for a country with our historical connection to entrepreneurship and innovation. The burden of federal regulations on small businesses has been increasing — between 2008 and 2012, the number of rules impacting small firms increased by 13 percent. Startups by definition do not benefit from the economies of scale in compliance that incumbents with their large balance sheets and teams of accountants, compliance officers, and in-house counsels enjoy. There is no question that the long-term decline in the startup rate corresponds with a steadily growing regulatory and tax compliance burden, which has made the prospect of starting and scaling a business more daunting over time.

Generational Factors

Some generation-specific factors may contribute to the pronounced absence of entrepreneurship among Millennials. Again there is no smoking gun, but several intuitive possibilities suggest themselves.

- Student Debt. For one thing, Millennials carry an ever-growing burden of student debt, which limits both preferences and capacities for risk-taking. Between 2004 and 2014, there was an 89 percent increase in the number of student borrowers, as well as a 77 percent increase in the average balance size held by student borrowers. While only 30 percent of students took out loans to finance their education in the mid-1990s, half of all students borrowed during the 2013–2014 school year.

- Lower homeownership. The rate of homeownership among Americans age 25–34 has fallen nearly 10 percentage points since 2004, meaning that fewer young people have, or are building, equity against which they can borrow either now or in the future to launch entrepreneurial ventures.

- Weaker economy and labor market. Many Millennials found themselves entering the labor market during the traumatic period of the Great Recession. Research has found that macroeconomic conditions in young adulthood impact future financial behavior, and that starting a career during a recession negatively impacts future earnings. Individuals who start their careers during a recession can expect their earnings to be between 2.5 percent and 9 percent lower than otherwise for their first 15 years in the labor market. The impact of the Great Recession will thus have a lasting impact on Millennials preference for risk and their financial ability to choose entrepreneurship down the road.

Policy Solutions

The complexity of the issues at hand requires a holistic rather than piecemeal approach. Today’s decline in business dynamism transcends the purview of any single committee, branch of government, or political party. Developing a coordinated, bipartisan approach is the only way forward if we hope to implement effective policies.

While there are no easy solutions, I’d like to mention a handful of immediate priorities that policymakers should begin to tackle:

Access to capital

EIG is particularly focused on policies that democratize access to capital, and here the federal government has a unique ability to effect change through innovative, market driven incentives.

One example is the Investing in Opportunity Act (S. 2868/H.R. 5082), which was recently introduced by two members of this committee, Senators Tim Scott (R-SC) and Cory Booker (D-NJ). This legislation proposes a novel way to encourage investment in startups, small businesses, and other enterprises in capital-starved communities. It is an idea that advances many public policy goals at once: if we care about expanding entrepreneurship, reducing geographic disparities, and rejuvenating distressed communities, it makes sense to tackle them in concert. The Investing in Opportunity Act does so by encouraging collective action from investors who on their own would likely lack the scale of capital, risk tolerance, or wherewithal to effectively deploy their resources distressed areas. I believe this legislation could serve as a model for federal engagement: providing a targeted incentive that corrects a market failure to generate prosperity in U.S. communities.

Getting more people and regions participating in the growth of entrepreneurial activity is a worthy goal for policymakers. As noted earlier, venture capital is highly concentrated; state and federal policies should seek to facilitate more broadly dispersed deal flow. Likewise, angel investors and crowdfunding platforms are key channels that allow capital to flow into geographically underserved areas and to underserved demographic groups, and public policy should support these efforts and other innovative financing mechanisms. But it took four years from the passage of the JOBS Act in 2012 to get crowdfunding regulations issued by the SEC, which is literally a lifetime for an entrepreneurs trying to start or grow a business. While crowdfunding holds considerable promise — some analysts expect the size of the market to surpass venture capital this year — the market remains immature and its viability as a source of large scale financing unproven (especially given the relatively cautious approach taken by the SEC).

Policy Experimentation

For a problem as urgent, complex, and important as this one, policymakers should strive to stoke experimentation wherever possible. The federal government, while not designed to move quickly on major issues, must be fundamentally focused on setting a broadly favorable policy and regulatory landscape within which states and cities have the flexibility to experiment as true laboratories of economic innovation. Federal policies can also do far better at using prizes and pilot programs to spur greater experimentation throughout government. New ideas may generate new constituencies and upend the conventional wisdom of what’s politically possible.

New ideas may generate new constituencies and upend the conventional wisdom of what’s politically possible.

Rules, regulations, and barriers to entry

It is a nearly universally accepted truth that the accumulation of rules and regulations in the economy not only discourages companies for forming but also gives incumbent firms an advantage. There are significant economies of scale to compliance, and the same regulation will impose a relatively greater cost on a smaller firm. Many regulations have a clear public policy purpose; their intent and merits are not my concern here. But any proposed rule or regulation should be thoroughly evaluated for its effect on startups new firm formation in particular. Many well-intentioned regulations will have unintended side effects that contribute to the declining dynamism documented here.

For example, recent research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond found the decline in community banks (a major source of capital for young firms and small businesses in communities outside the traditional hubs) can mainly be attributed itself to the unprecedented decline in new bank entrants, rather than an exceptional increase in failures or acquisitions. One can presume that changes in the regulatory environment in the financial industry have played a meaningful role in discouraging new community banks from forming — or preventing them from being able to compete with far larger ones. Indeed a recent Government Accountability Office report found that community banks and credit unions are struggling to meet the requirements of new regulations and reducing certain types of business lending in response.

Occupational Licensing

The proliferation of unnecessarily onerous occupational licensing represents a clear case in which vested interests have hijacked public policy to protect themselves and close the door on outsiders aspiring to chart their own career paths. The share of jobs in the economy requiring a license to practice rose from 5 percent in the 1950s to 29 percent by 2008. While licensing requirements make sense for certain occupations, many act as anticompetitive barriers to entry with little public policy justification. Relatively low-earning workers and would-be entrepreneurs in basic services industries such as hairdressing or tour-guiding bear the brunt of unnecessary restrictions. Licensing also impedes geographic mobility — an important mechanism for counteracting regional inequality — by preventing workers from transferring their skills to more opportunity-rich locales. This may be a contributing factor to the steep decline since the mid-2000s in long distance migration.

While occupational licensing is primarily in state legislatures’ jurisdictions, federal agencies and bodies such as this committee can play a critical role in spotlighting licensing abuses, exposing discrepancies across states, and encouraging harmonization and reciprocity.

Better data

Finally, we don’t actually know much about the problem yet and economists are still establishing the facts. They need help with that, and the federal government is uniquely positioned to provide the public good of data and information that can quantify the magnitude and consequences of the trend. For example, we would remain totally ignorant of this crisis were it not for federal investments in the Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics program or the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ JOLTs (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) program. An increase in federal support for the Census Bureau (particularly the Census Center for Economic Studies) and the IRS in their collaborative data collection efforts is a necessary step to ensure access to relevant data. In exchange for expanded funding, agencies should be required to make more of their data public and do it in a more timely fashion.

Continuing to fund other sources of data collection that capture trends in our economy’s dynamism, from the BLS’s contingent worker survey to the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics at the University of Michigan, should also be prioritized so that policymakers have the facts they need to inform their responses to the troubling trends at hand. In addition, a task force with representatives from across government, academia, think tanks, and the private sector could be convened to expand and modernize the federal government’s data collection enterprise for a 21st century economy. The economy has transformed and so have the challenges facing us today. The tools we use to understand the economy need to evolve too.

Conclusion

The decline in entrepreneurship represents a national crisis requiring immediate, concentrated, and coordinated attention. The full consequences of this development are not yet fully understood and will only manifest themselves over time, but the longer we wait, the higher the likelihood we burden the next generation with an economy fundamentally transformed for the worse.

In the wake of the Great Recession and in the midst of our nascent recovery, we must recommit to fostering this country’s entrepreneurial potential.

We’ve arrived at another critical juncture in our history. In the wake of the Great Recession and in the midst of our nascent recovery, we must recommit to fostering this country’s entrepreneurial potential. If we succeed, we’ll begin making inroads against the many pressing challenges confronting Americans in every state and community.

Thank you.