April 26, 2017: John W Lettieri, Economic Innovation Group

*Watch the full hearing here.

Chairman Risch, Ranking Member Shaheen, and members of the committee, it is an honor to again have the opportunity to testify before this committee.

The state of rural America is an issue of much interest and debate today. Rural entrepreneurship and economic dynamism are at a particularly important inflection point, as the geography of economic growth and opportunity has shifted decisively toward denser and more metropolitan locations in recent years.

My testimony today can be summarized as follows:

- Rural America is not monolithic; many areas are doing quite well, and dramatic regional variations limit the usefulness of broad generalities in describing rural economies.

- The true fault line is not between rural and urban communities but rather between communities that are highly connected and those that are isolated. Increasing the connectivity of rural communities in terms of access to infrastructure, global markets, capital markets, the Internet, and human capital is essential for their future success.

- Nevertheless, there is a widespread and irreversible shift towards density in the modern economy that presents unique challenges for rural and small town entrepreneurship.

- Meeting these challenges will require rural America to reinvent itself for the future, not cling to past models of growth and industry. In doing so, state and local stakeholders will be the most essential. There is simply no substitute for local leadership.

- Policies that help restore higher rates of dynamism, innovation, and growth for the nation as a whole will be good for those who live in rural America — whether or not they choose to remain in rural communities. Such policies should be the primary focus of federal policymakers, with secondary considerations given to place-specific initiatives.

Defining “Rural”

One of the key challenges in evaluating rural America lies in defining it. There is simply not a single definition of what constitutes a rural community, and the statistical agencies use a variety of methods and metrics to assess rural economies. My testimony will draw from the three most common approaches. First, rurality can be determined by the population density of a community, which the Census Bureau does. Rural areas can also be defined at the county level as those outside of metropolitan areas, as the Bureau of Economic Analysis and Department of Agriculture do. Finally, it often makes sense to classify counties based on their population size, since counties of similar size classes seem to encounter similar economic trends in an age in which the returns to size and density appear to be rising. This is an approach EIG often takes in its work.

Definitional complexities aside, there is much we can glean from available data, beginning with the fact that rural America is not monolithic. While frequently lumped together, rural economies, histories, and communities in fact vary greatly. A prosperous farming community in the northern plains has little in common with the deep-rooted poverty of the Mississippi River basin.

Fully 54 percent of the country’s officially “rural” population actually resides in a metropolitan area. (1) These communities share inextricable economic ties to their broader regions, and their fates are often tied to larger metropolitan fates. As categories, “urban” and “rural” are better understood as a gradient than a dichotomy. In many ways small and even mid-sized cities stand right alongside many rural areas in navigating the same economic headwinds.

Indeed, the true dichotomy today is not between urban and rural but rather between connected and isolated. Highly connected communities — ones linked to global markets, human capital, infrastructure, and knowledge centers — will be best positioned to thrive in the emerging economy.

Survey of Rural America

It is no secret that cities are increasingly important as centers for economic growth and vitality. The rural economy, however, has in many ways been remarkably resilient and is not, as a whole, doing as poorly as is commonly believed.

Demographics

Rural demographics show characteristics of stability, but not necessarily in ways that are likely to provide an economic boost. Rural Americans are older than their urban peers, with a median age of 43.5 versus 36.6 in cities. Nearly 60 percent of rural households are married (compared to 46 percent in urban areas), and more than three quarters of children live in a married couple household — which research shows is good for fostering upward mobility. (2) Only 3.3 percent of the rural population was born outside of the United States. (3) That figure is nearly five times higher in urban areas. As the United States faces its slowest population growth rate since the Great Depression, this urban-rural disparity in immigrant population will likely exacerbate rural demographic challenges in the years to come. While depopulation doesn’t afflict all rural communities and population growth was stable in 2015, small counties comprised 95 percent of the 1,700 counties that lost population from 2010 to 2014. (4) Attesting to the diversity of rural regions, Figure 1 below shows that immigration from abroad did either offset the loss of native-born residents or slow the overall rate of population decline across a large swath of the central plains.

Population trends matter because population is a proxy for the size of the market or customer base in a location. As the number of local customers entrepreneurs can reach declines, connectivity to larger markets becomes all the more important to sustain their business. Nearly three-quarters of the small counties that lost population from 2010 to 2014 also lost business establishments, according to EIG’s research. (5) Furthermore, population growth, immigration, and business dynamism are closely linked, as we will explore later in my testimony.

The size of the country’s rural population has held remarkably stable for decades: the 59.5 million Americans living in rural areas in 2010 was the same number as in 1980 and only slightly higher than the 57.5 million in 1940. (6) The difference is that the urban population has grown inexorably, which is likely to continue. The rural economy has evolved with the country, and policymakers’ challenge today is to ensure that it can continue to find new economic purposes in the decades to come.

Employment, earnings and poverty

Employment increased by 4 percent between 2010 and 2015 in nonmetropolitan counties, but nonmetropolitan counties still contained fewer jobs in 2015 than they did in 2007. By contrast, metropolitan employment increased by 11 percent over the same period — adding more than 10 million jobs to metropolitan America’s pre-recession peak. (7)

While median household income is lower in rural areas ($52,400) compared to urban areas ($54,300), the differential is offset somewhat by lower costs of living. (8) The real gap is between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas: Median household income outside of metropolitan areas is only 75 percent of median household income within metropolitan areas ($44,700 compared to $59,300 in 2016). (9)

Rural residents are more likely than their urban peers to live above the poverty line. The rural poverty rate was 13.3 percent in 2015 compared to 16.0 percent in urban areas. (10) However, new research by the Brookings Institution finds the “working poor” is more rural than urban, relatively speaking. According to Brookings, 22 percent of the rural population is EITC-eligible, compared to 18 percent in large metro areas. (11) The gap between rural and urban poverty rates is highest in the South. (12) And the vast majority — 85 percent — of the country’s persistently poor counties are rural. These are counties that have had over a 20 percent poverty rate for at least 30 years. Not coincidentally, many of these post low educational attainment rates. (13)

Economic specializations

Rural areas specialize in a wide variety of economic activities, from agriculture to natural resource extraction to tourism and recreation. The USDA’s Economic Research Service classifies nonmetropolitan counties according to the dominant economic activity taking place within them, providing a useful way for differentiating across rural America and disentangling the variety of economic trends facing different types of rural communities.

For example, farming-dependent rural economies are depopulating fastest as agriculture automates and workforce requirements change. By contrast, many mining-dependent counties have seen large recent increases in population thanks to the boom in oil and gas drilling, although this growth may soon start to reverse as the boom subsides. Manufacturing-dependent counties, representing nearly one in five nonmetropolitan counties, have struggled alongside small and mid-sized metro areas battling the same headwinds. Recreation-dependent counties, often endowed with spectacular natural amenities, register high population growth rates and the highest median incomes among the different categories. By contrast, both public sector-dependent and non-specialized counties suffer with low wages and high poverty rates in the absence of robust private-sector activity. (14)

Of course, some counties combine multiple specializations to build a diversified economic base. The prospering rural Shenandoah Valley, for example, combines recreation with farming as well as warehousing and distribution and even high-end services, thanks to good infrastructure, proximity to metropolitan hubs, and a network of universities.

The differentiation of rural economies underscores the need for policy solutions to be organic and rooted in the rural economy. Policies can be neither top-down nor one-size-fits-all. Policy should seek to nurture rural entrepreneurship in its own ecosystem, reducing barriers, shrinking distances, promoting access to markets and capital.

Upward Mobility in Rural America

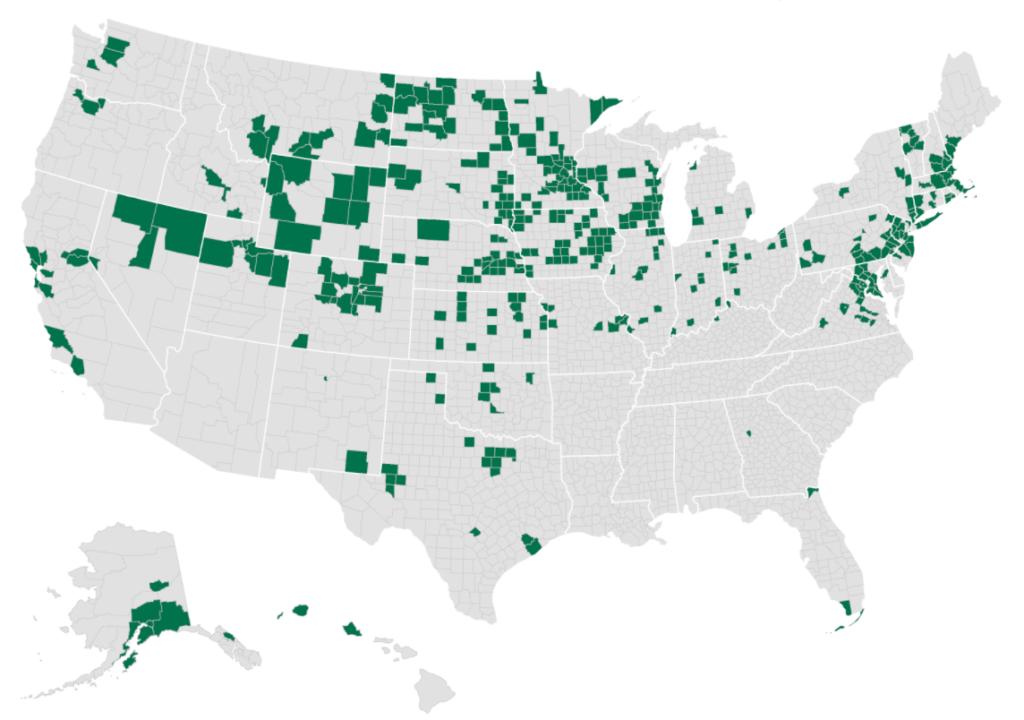

Rural areas have historically provided some of the highest rates of upward economic mobility in the United States. EIG analyzed data from its Distressed Communities Index and the Equality of Opportunity Project’s estimates of place-based impacts on children’s future earnings potential and found that 64 percent of all U.S. counties that are both prosperous today and have a history of fostering economic mobility are counties with fewer than 100,000 people. As shown in Figure 2 below, more than four out of five of these counties are scattered across the Midwest and Mountain West, painting a broad swath of prosperity and upward mobility across the northern tier of the nation.

Counties that are both prosperous and foster upward mobility for poor kids. Source: EIG’s analysis of Distressed Communities Index and Equality of Opportunity Project Data.

These places have unique histories, strong social capital, and a deeply ingrained culture of work. Unemployment rates in the region are some of the lowest and labor force participation rates some of the highest nationwide. On average, 92 percent of the adult population has completed high school in these counties (compared to 86 percent nationwide), and only 35 percent of the over-16 population (which includes retirees) is not working (compared to 42 percent nationwide). Approximately 75 percent of children in these counties are raised in traditional married two-parent households. These counties (prosperous, upwardly mobile, and in the Midwest or Mountain West) are far less diverse than the country as a whole, however, with average minority populations of only 9 percent. (15)

At the same time, another large swath of rural America is a land of missing opportunity and of perpetual, persistent poverty. An astonishing 98 percent of counties that are both economically distressed and have a history of dragging down children’s future earnings potential are small counties, and of those, 85 percent are located in the South. In these counties, nearly a quarter of adults have not graduated high school and 55 percent of the adult population (everyone over 16) is not working. Approximately 44 percent of children in these counties grow up in non-traditional family arrangements. (16)

A Challenging Recovery

The Great Recession and the subsequent uneven recovery were unkind to small and rural counties. Nationally, a dismal 59 percent of U.S. counties saw more business establishments close than open during the first five years of the national recovery. (17) But in small counties, it was even higher at 64 percent. Likewise, 36 percent of counties under 100,000 residents saw employment declines over the same period, versus 31 percent of all U.S. counties. (18) Population shifts are also a factor, as 63 percent of small counties saw a net loss of population during the recovery. (19) In spite of broader national growth, more than one in five small counties experienced a net loss in all three categories: business establishments, employment, and population. On the other hand, 21 percent of small counties still managed to match the national establishment growth rate. These counties could be found throughout the country, from North Dakota to West Virginia, underscoring the resilience of many rural counties in bucking broader trends. (20)

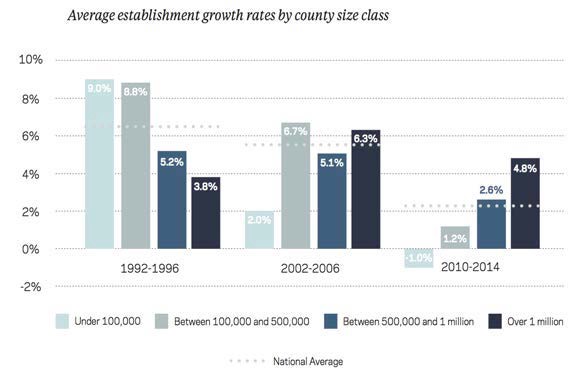

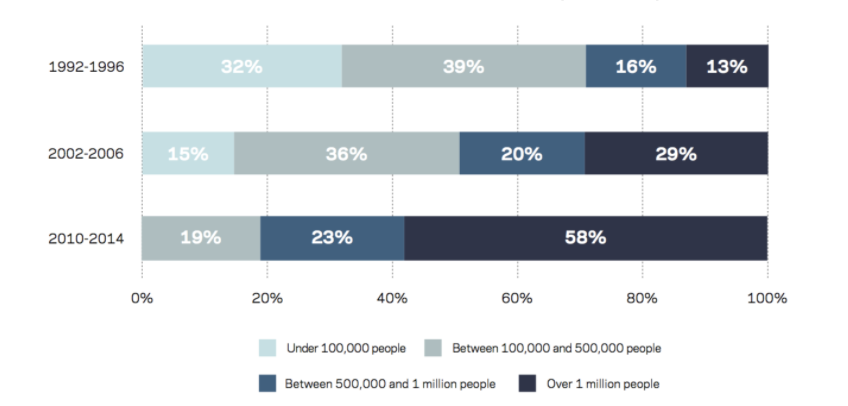

The current recovery period also seems to have cemented a rather dramatic reversal of fortune in favor of densely populated areas in the distribution of job and business establishments. As recently as the mid-1990s, small counties led the nation in the rates of establishment and employment growth, while large counties posted the lowest rates in both categories. EIG’s research shows that patterns of economic growth now strongly favor large urban counties, which is demonstrated in Figures 3 through 5 below. (21)

The regional reversal is especially stark when considering small counties’ share of national net growth in business establishments. From 1992 to 1996, nearly one third of the net growth in U.S. establishments was housed in counties with under 100,000 residents. By the 2010s, these counties, which had once been such a promising engine of business growth, actually saw a net decline in their total number of establishments. Meanwhile, the counties with over one million in population had seen their share of net establishment growth go from 13 percent to a whopping 58 percent. (22)

Two Key Divergences: Education Attainment and the Services Economy

The present reality of rural economies diverges starkly from the trajectory of the U.S. economy in two deeply important ways that will impact the future of rural entrepreneurship and access to opportunity.

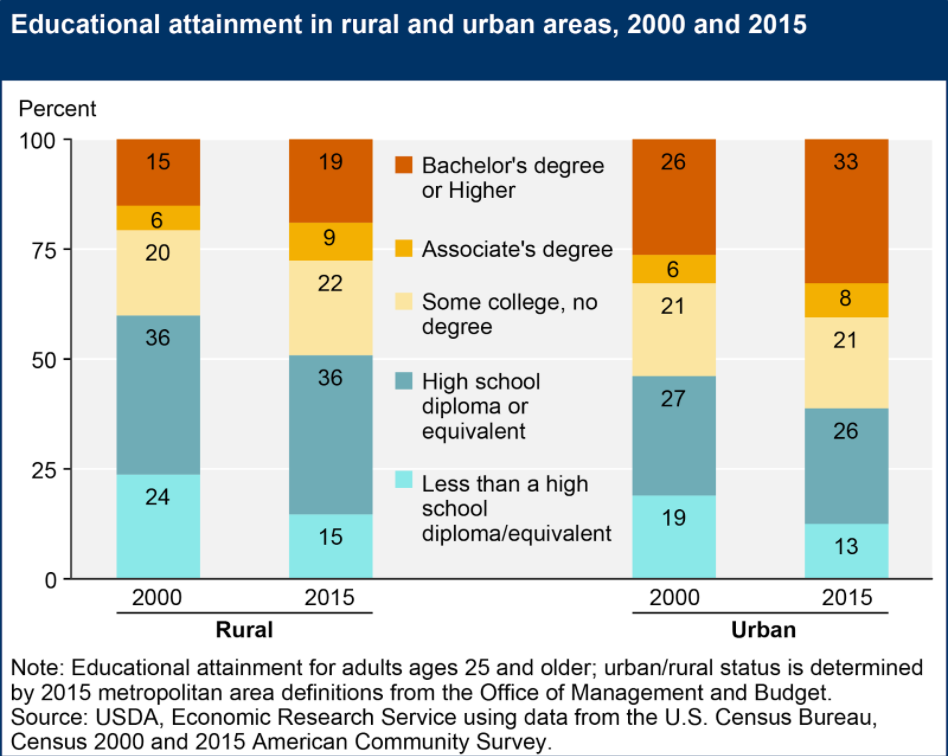

The first divergence is that educational attainment in rural areas badly lags the rest of the country. In an economy increasingly defined by “knowledge” work and cognitive skills, this limits opportunities from the individual perspective but also undermines the ability of firms or industries to locate operations in rural areas. In short, the education gap makes it harder for rural individuals to obtain jobs and harder for companies to consider rural locations.

- Only 19 percent of the rural population has a bachelor’s degree, compared to 33 percent in metropolitan areas. Fully 51 percent of rural residents have no schooling beyond high school, compared to 39 percent in metro areas. (23)

- Even for the younger 25–34 year old cohort, the college attainment rate increased by 5 percentage points to 20 percent in rural areas compared to 7 percentage points to 36 percent in metropolitan areas from 2000 to 2015. (24)

- The gap in college attainment between the rural and metropolitan population has actually widened over the past 15 years. (25)

It is difficult to overstate the importance of this trend. Recent research presents a bleak and somewhat stunning picture of economic and social malaise for Americans, notably white Americans, of lower education attainment. Mortality itself is rising within that group. (26)

The second and related divergence is that one of the largest, fastest growing, and highest paying sectors in the economy — business services — is extremely urbanized, much more so than manufacturing. Rural areas are home to 13 percent of all U.S. employment and 19 percent of all manufacturing employment but only 6 percent of all jobs in the information and professional, scientific, and technical services sectors. (27) These “knowledge economy” industries thrive in urban environments with deep talent pools and high levels of connectivity. The story of diverging economic performance is rooted in the concentration of this sector in particular.

The undersized rural services sector underscores why increasing connectivity is so important: to increase the number of potential customers and clients rural entrepreneurs can reach. The policy question is how to reduce the barriers facing rural individuals to tapping into opportunities in this growing, future-oriented sector.

Rural Entrepreneurship and Economic Dynamism

Before looking specifically at rural entrepreneurship, let’s take a moment to consider the national picture. Since the onset of the Great Recession, the United States has experienced a rapid and persistent collapse in the rate of firm formation (the “startup rate”). The national drop in startup activity is at the heart of a broader decline of economic dynamism that extends to historically low rates of labor market fluidity and geographic mobility among American workers, rapid market consolidation and growing advantages for large incumbents in most industries, and steep differences in the distribution of new jobs and businesses between regions.

The startup slowdown

These national trends harbor troubling signs for rural regions. The slowdown in new firm formation started earlier and has been more severe in rural areas than in non-rural economies.

- New companies are much less likely to form in rural areas than in urban ones today. Nationally, as of 2014, 8.0 percent of all firms in the economy were started in the past year; in metropolitan areas the figure was 8.3 percent and in non-metropolitan areas it was 6.1 percent. (28)

- In absolute terms, over 355,000 new companies formed in the metropolitan United States in 2014; in non-metropolitan areas the figure dipped below 50,000, to 49,100, for the first time on record. This all-time low means that half as many firms started in nonmetropolitan regions in the 2010s as did in the late 1970s or early 1980s, even though the rural population has remained relatively stable. The steep national slowdown in new firm formation started earlier and has cut even deeper in rural areas. (29)

- Rural areas do not suffer from disproportionate rates of firm closures. In 2014, 7.1 percent of firms closed in nonmetropolitan areas, compared to 7.8 percent of firms in metropolitan areas.

- Taken into consideration with the firm startup rate, the key differentiating factor between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties is subdued dynamism in general — and depressed rates of new firm formation in particular. In other words, the crisis isn’t that shops on Main Street are closing; they’re doing that at roughly the same rate they have for many years. Rather, with a startup rate now a full percentage point below the closure rate, the problem is new businesses are no longer emerging quickly enough to take the place of those dying out through the natural course of competition and economic change.

Rural economies today are simply experiencing less change than metropolitan economies and producing fewer new “shots on goal” — new companies. With that comes reduced flexibility, less resiliency, and fewer new enterprises experimenting with new business models and taking new risks. Rural entrepreneurship is an absolute prerequisite for rural economic adaptation and for ensuring that rural areas find new lives in an ever-changing global economy.

The state of economic dynamism in rural areas

EIG has conducted a significant amount of research into what makes a dynamic, entrepreneurial economy. Density certainly fosters dynamism, but the ingredients of a dynamic local economy are not confined to urban areas.

Dynamism starts with entrepreneurship but extends much more widely to encompass individuals migrating to economic opportunity, workers moving into more productive work arrangements, and markets remaining competitive. Forthcoming research from EIG finds that dynamism trends across states tend to hold over long periods of time, making inertia difficult to reverse. Population growth in particular provides substantial fuel for economic dynamism; places without it face an uphill — but by no means impossible — climb.

Several rural states suffer neither from exceptionally low startup rates nor from exceptionally high firm closure rates. Instead, it is the gap between the two rates locally that signals a dynamism problem — notably in West Virginia, Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, New Hampshire, and Iowa. (30) With already relatively low rates of firm closures, boosting the firm creation rate is required to make sure these economies remain “above water” when it comes to entrepreneurship and the economic opportunity and local dynamism it fosters.

Another measure of economic dynamism is the share of a state’s workforce employed in firms less than one year old. Here the Dakotas, both among the 10 most rural states, land in the top 10 for jobs in new companies, too. Wyoming is not far behind in terms of startup jobs and ranks in the top 10 nationwide in terms of both net in-migration and the rate at which workers turn over among firms, an important metric of economic resilience and input into productivity growth. Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho all have among the smallest shares of their population employed in old incumbent firms, suggesting that their economies are relatively young — and incumbent interests perhaps features less prominently on the economic (and therefore political) landscape.

At the end of the day, high rates of labor force participation signal an economy that’s working well and working for working people. The top 10 states in terms of employed persons per share of the adult population are: North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Utah, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Vermont.

In general, rurality seems to be most disadvantageous when it comes to population growth (absent an economic boom such as drilling in the Dakotas) and in the sheer volume of turnover among companies — both openings and closings combined.

The mentality of self-help and initiative found in many rural areas is inherently entrepreneurial. We need to harness that energy and those natural inclinations to make sure that viable enterprises can start and scale wherever someone wants to try.

The Changing Face of Entrepreneurship

Much has been made of the potential of the Internet to provide rural areas with a new lease on economic life. While the Census Bureau’s statistics on “non-employer businesses” (which capture sole proprietors and other independent workers) shows steady growth in urban areas but no real uptick in rural ones, evidence can be found elsewhere that the so-called “platform-enabled gig economy” has indeed opened up new avenues for entrepreneurial activity in rural America (provided a fast Internet connection is available, of course). As the expansion of traditional firms and business establishments has stalled in small counties, platform-enabled entrepreneurship is on the rise.

- According to Etsy’s Seller Census, 28 percent of the platform’s 1.7 million sellers live in rural communities, compared to 17 percent of non-farm business owners nationwide and 18 percent of the total population. (31)

- A recent report from eBay compiling statistics on their commercial sellers found that new sellers who started operations from 2010 to 2014 were significantly less geographically concentrated than the formal business establishments that opened over the same time (and which EIG analyzed in its “New Map of Economic Growth and Recovery” report). Furthermore, 32 of the 100 counties with the highest number and revenue of eBay commercial sellers per capita are rural counties — one of the very few lists on which you’ll see small rural counties such as Essex County, VT; Clay County, NC; and Flagler County, FL score right alongside Santa Clara County, CA; New York County (Manhattan), NY; and Miami-Dade County, FL. (32)

- Thumbtack, a relatively new online marketplace for local services, has connected independent providers with customers in every county in the country bar one. (33)

- Upwork’s Freelancing in America survey estimates that 18 percent of freelancers live in rural areas — roughly equivalent to the rural share of the population. The survey reinforces the fact that Internet connectivity is crucial to making sure that the “future of work” is open to rural residents: 66 percent of all freelancers said that the amount of their work done online in the past year increased and 54 percent obtained jobs online in 2016, up from 42 percent two years prior. (34)

The nature of entrepreneurial behavior in rural areas is inherently different than more densely populated areas, but the penchant often runs deep. In certain rural areas, especially in the plains, self-employment and multiple job-holding already run high. (35) Taking advantage of the reach and scale enabled by web-based platforms should be a natural step. However, the rise in platform-enabled opportunities, while welcome, is not likely to provide an ample substitute for a missing generation of new firms in much of rural America. This is because new firms have a greater impact in terms of hiring, innovation, and a host of other economic activities.

Looking to the Future: What is a “connected” rural economy?

As mentioned at the outset, highly-connected local economies are those best positioned to thrive in the new economy. The most important economic divide today is not between urban and rural but rather between connected and isolated. For example, Headwaters Economics, a research organization based in the Mountain West, classifies western counties according to three categories: those that are metropolitan, those that are rural but connected via daily air service to a larger hub, and those that are rural and isolated. Rural but connected economies have higher median incomes, lower income volatility, more high-wage service jobs, lower median ages, higher population growth, and greater educational attainment than their isolated peers. (36)

Thus, policymakers should be focused on policies that help to strengthen and expand connectivity in all its different forms for rural communities. Modernizing and repairing U.S. infrastructure is one obvious example. So too is ensuring rural entrepreneurs have better access to capital, especially via new platforms like crowdfunding and smart regional incentives that avoid hollowing out the local tax base. Another priority should be closing the “digital divide” between urban and rural areas: 39 percent of rural Americans lack access to broadband compared to only 4 percent of urban Americans. (37)

Access to global markets is another key element of connectivity. Trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) support millions of American jobs, including a great many in rural and small town communities. (38) These “insourcing” jobs tend to be higher-paying and disproportionately linked to manufacturing and innovation — in other words, exactly the kind of jobs rural communities need. In Alabama, for example, over 80 percent of all jobs in foreign-owned establishments are located outside of the Birmingham metropolitan area. (39)

Connectivity extends to human capital, as well. Physical and digital infrastructure support flows of people and ideas, but cognitive openness is important too. Workers need skills that are up-to-date and in-demand. Entrepreneurs need to be plugged in to broader market trends. Workers need to be unencumbered in their ability to move to areas of greater economic opportunity — urban as well as rural. Community colleges and workforce training programs need to support life-long learning. Universities, embedded in national and global knowledge networks, will be linchpins of local economic development efforts. The economy is evolving in directions that demand more human capital; rural areas have significant ground to make up if they hope to thrive.

Conclusion

People are generally quite bad at predicting the future. This includes, unfortunately, policy experts. For example, leading thinkers in the postwar period were actually worried about what they believed to be a looming crisis of too much leisure time as the need for long work hours diminished. In 1959 the Harvard Business Review bemoaned that “boredom, which used to bother only aristocrats, had become a common curse.” (40) Few today would say too much leisure is a defining characteristic of American life. More recently, the rise of the Internet was supposed to flatten the world and make location irrelevant; instead, the relationship between geography and opportunity appears more profound than ever.

These examples illustrate a fundamental truth: we don’t know what the world of the future will look like. Rather than trying to predict or prescribe the economy of the future, our goal should be to ensure the broader economy remains as flexible, dynamic, and adaptable as possible. Rural communities no doubt face challenges — most importantly, the challenge of adapting to an economy that increasingly rewards density and knowledge-based industries. It is important not to overstate or misinterpret those challenges. Rural communities also often have advantages that can help level the playing field, including quality of life, affordable and available land, access to natural resources, and strong social cohesion. Matching those local advantages with a national policy environment that promotes connectivity is essential. There is no substitute, however, for local leadership or local solutions. Therefore, an element of caution is needed when considering place-based federal solutions. When designed well, they can be of tremendous benefit. But even the best place-based policies will be of limited use absent a broad-based, pro-growth policy framework. In crafting such an agenda, we must avoid and eliminate policies that — even when well intentioned — tilt the balance too far in favor of guarantees versus opportunities; incumbents versus upstarts; today’s jobs versus tomorrow’s; or certainty versus healthy risk-taking.

Thank you and I look forward to answering your questions.

Citations

(1) U.S. Census Bureau Rural America: A Story Map. and Berube, Alan, “Political Rhetoric Exaggerates Economic Divisions Between Rural and Urban America.” (Brookings Institution, 2016).

(2) U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 5 Year Estimates for 2010–2014. Chetty, Raj and Nathaniel Hendren, “The Effects of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility II: County-Level Estimates.” (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper №22910, 2016).

(3) Economic Innovation Group’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 5 Year Estimates for 2010–2014.

(4) U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services’ and Economic Innovation Group’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

(5) EIG’s analysis of Census’ Business Dynamics Statistics and Population Estimates.

(6) “Measuring America: Our Changing Landscape.” U.S. Census Bureau (2016).

(7) EIG’s analysis of Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

(8) Bishaw, Alemayehu and Kirby Posey, “A Comparison of Rural and Urban America: Household Income and Poverty.” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016).

(9) U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey, 2016.

(10) Bishaw and Posey, 2016.

(11)Murray, Cecile and Elizabeth Kneebone, “The Earned Income Tax Credit and the White Working Class.” (Brookings Institution, 2017).

(12) Bishaw and Posey, 2016.

(13) USDA, Economic Research Service Geography of Poverty, 2017.

(14) USDA, Economic Research Service Description and Maps: County Economic Types, 2015 Edition.

(15) EIG’s analysis of Census’ ACS 5 Year Estimates for 2010–2014.

(16) EIG’s analysis of Census’ ACS 5 Year Estimates for 2010–2014.

(17) EIG, May 2016: 6–7.

(18) EIG’s analysis of Census’ County Business Patterns data.

(19) EIG’s analysis of Census’ Population Estimates data.

(20) EIG’s analysis of Census’ County Business Patterns and Population Estimates data.

(21) “The New Map of Economic Growth and Recovery.” Economic Innovation Group (May 2016): 22–25.

(22) EIG, May 2016: 22–25.

(23) USDA, Economic Research Service analysis of Census’ ACS for 2000 and 2015.

(24) EIG’s analysis of Census’ ACS 5 Year Estimates for 2010–2014.

(25) USDA, Economic Research Service analysis of Census’ ACS for 2000 and 2015.

(26) Case, Ann and Angus Deaton, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2017.

(27) EIG’s analysis of Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

(28) EIG’s analysis of Census’ Business Dynamics Statistics data.

(29) EIG’s analysis of BEA data.

(30) EIG’s analysis of Census’ Business Dynamics Statistics data. Unless otherwise cited, all statistics cited in this section are from this source.

(31) “Crafting the Future of Work: The Big Impact of Microbusinesses.” Etsy (2017).

(32) “Platform-enabled Small Businesses and the Geography of Recovery: Evidence of More Inclusive New Enterprise Growth on eBay than Reflected in Official Statistics.” eBay (January 2017).

(33) Information provided by Thumbtack, April 21, 2017.

(34) “Freelancing in America: 2016.” Upwork and Freelancer’s Union commissioned study conducted by Edelman Intelligence (October 2016).

(35) Hipple, Steven and Laurel Hammond, “Self-employment in the United States.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016) and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Multiple Job Holdings in States in 2015, 2017.

(36) Headwaters Economics, “Three Wests: The Impact of Access to Markets on Economic Performance in the West,” 2015.

(37) “2016 Broadband Progress Report.” Federal Communications Commission (2016) and Karsten, Jack and Darrell West, “Rural and Urban American Divided by Broadband Access.” (Brookings Institution, 2016).

(38) “Top Level Facts: Operations of Majority-Owned U.S. Affiliates of Foreign Multinational Enterprises August 2016 BEA Release.” Content First, LLC.

(39) Saha, Devashree, Kenan Fikri, and Nick Marchio, “FDI in U.S. Metro Areas: The Geography of Jobs in Foreign Owned Establishments.” Brookings Institution and JPMorgan Chase & Company (2014).

(40) Rosen, Rebecca, “Money-Rich and Time-Poor: Life in Two-Income Households.” (The Atlantic, 2015).

April 26, 2017: John W Lettieri, Economic Innovation Group

*Watch the full hearing here.

Chairman Risch, Ranking Member Shaheen, and members of the committee, it is an honor to again have the opportunity to testify before this committee.

The state of rural America is an issue of much interest and debate today. Rural entrepreneurship and economic dynamism are at a particularly important inflection point, as the geography of economic growth and opportunity has shifted decisively toward denser and more metropolitan locations in recent years.

My testimony today can be summarized as follows:

Defining “Rural”

One of the key challenges in evaluating rural America lies in defining it. There is simply not a single definition of what constitutes a rural community, and the statistical agencies use a variety of methods and metrics to assess rural economies. My testimony will draw from the three most common approaches. First, rurality can be determined by the population density of a community, which the Census Bureau does. Rural areas can also be defined at the county level as those outside of metropolitan areas, as the Bureau of Economic Analysis and Department of Agriculture do. Finally, it often makes sense to classify counties based on their population size, since counties of similar size classes seem to encounter similar economic trends in an age in which the returns to size and density appear to be rising. This is an approach EIG often takes in its work.

Definitional complexities aside, there is much we can glean from available data, beginning with the fact that rural America is not monolithic. While frequently lumped together, rural economies, histories, and communities in fact vary greatly. A prosperous farming community in the northern plains has little in common with the deep-rooted poverty of the Mississippi River basin.

Fully 54 percent of the country’s officially “rural” population actually resides in a metropolitan area. (1) These communities share inextricable economic ties to their broader regions, and their fates are often tied to larger metropolitan fates. As categories, “urban” and “rural” are better understood as a gradient than a dichotomy. In many ways small and even mid-sized cities stand right alongside many rural areas in navigating the same economic headwinds.

Indeed, the true dichotomy today is not between urban and rural but rather between connected and isolated. Highly connected communities — ones linked to global markets, human capital, infrastructure, and knowledge centers — will be best positioned to thrive in the emerging economy.

Survey of Rural America

It is no secret that cities are increasingly important as centers for economic growth and vitality. The rural economy, however, has in many ways been remarkably resilient and is not, as a whole, doing as poorly as is commonly believed.

Demographics

Rural demographics show characteristics of stability, but not necessarily in ways that are likely to provide an economic boost. Rural Americans are older than their urban peers, with a median age of 43.5 versus 36.6 in cities. Nearly 60 percent of rural households are married (compared to 46 percent in urban areas), and more than three quarters of children live in a married couple household — which research shows is good for fostering upward mobility. (2) Only 3.3 percent of the rural population was born outside of the United States. (3) That figure is nearly five times higher in urban areas. As the United States faces its slowest population growth rate since the Great Depression, this urban-rural disparity in immigrant population will likely exacerbate rural demographic challenges in the years to come. While depopulation doesn’t afflict all rural communities and population growth was stable in 2015, small counties comprised 95 percent of the 1,700 counties that lost population from 2010 to 2014. (4) Attesting to the diversity of rural regions, Figure 1 below shows that immigration from abroad did either offset the loss of native-born residents or slow the overall rate of population decline across a large swath of the central plains.

Population trends matter because population is a proxy for the size of the market or customer base in a location. As the number of local customers entrepreneurs can reach declines, connectivity to larger markets becomes all the more important to sustain their business. Nearly three-quarters of the small counties that lost population from 2010 to 2014 also lost business establishments, according to EIG’s research. (5) Furthermore, population growth, immigration, and business dynamism are closely linked, as we will explore later in my testimony.

The size of the country’s rural population has held remarkably stable for decades: the 59.5 million Americans living in rural areas in 2010 was the same number as in 1980 and only slightly higher than the 57.5 million in 1940. (6) The difference is that the urban population has grown inexorably, which is likely to continue. The rural economy has evolved with the country, and policymakers’ challenge today is to ensure that it can continue to find new economic purposes in the decades to come.

Employment, earnings and poverty

Employment increased by 4 percent between 2010 and 2015 in nonmetropolitan counties, but nonmetropolitan counties still contained fewer jobs in 2015 than they did in 2007. By contrast, metropolitan employment increased by 11 percent over the same period — adding more than 10 million jobs to metropolitan America’s pre-recession peak. (7)

While median household income is lower in rural areas ($52,400) compared to urban areas ($54,300), the differential is offset somewhat by lower costs of living. (8) The real gap is between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas: Median household income outside of metropolitan areas is only 75 percent of median household income within metropolitan areas ($44,700 compared to $59,300 in 2016). (9)

Rural residents are more likely than their urban peers to live above the poverty line. The rural poverty rate was 13.3 percent in 2015 compared to 16.0 percent in urban areas. (10) However, new research by the Brookings Institution finds the “working poor” is more rural than urban, relatively speaking. According to Brookings, 22 percent of the rural population is EITC-eligible, compared to 18 percent in large metro areas. (11) The gap between rural and urban poverty rates is highest in the South. (12) And the vast majority — 85 percent — of the country’s persistently poor counties are rural. These are counties that have had over a 20 percent poverty rate for at least 30 years. Not coincidentally, many of these post low educational attainment rates. (13)

Economic specializations

Rural areas specialize in a wide variety of economic activities, from agriculture to natural resource extraction to tourism and recreation. The USDA’s Economic Research Service classifies nonmetropolitan counties according to the dominant economic activity taking place within them, providing a useful way for differentiating across rural America and disentangling the variety of economic trends facing different types of rural communities.

For example, farming-dependent rural economies are depopulating fastest as agriculture automates and workforce requirements change. By contrast, many mining-dependent counties have seen large recent increases in population thanks to the boom in oil and gas drilling, although this growth may soon start to reverse as the boom subsides. Manufacturing-dependent counties, representing nearly one in five nonmetropolitan counties, have struggled alongside small and mid-sized metro areas battling the same headwinds. Recreation-dependent counties, often endowed with spectacular natural amenities, register high population growth rates and the highest median incomes among the different categories. By contrast, both public sector-dependent and non-specialized counties suffer with low wages and high poverty rates in the absence of robust private-sector activity. (14)

Of course, some counties combine multiple specializations to build a diversified economic base. The prospering rural Shenandoah Valley, for example, combines recreation with farming as well as warehousing and distribution and even high-end services, thanks to good infrastructure, proximity to metropolitan hubs, and a network of universities.

The differentiation of rural economies underscores the need for policy solutions to be organic and rooted in the rural economy. Policies can be neither top-down nor one-size-fits-all. Policy should seek to nurture rural entrepreneurship in its own ecosystem, reducing barriers, shrinking distances, promoting access to markets and capital.

Upward Mobility in Rural America

Rural areas have historically provided some of the highest rates of upward economic mobility in the United States. EIG analyzed data from its Distressed Communities Index and the Equality of Opportunity Project’s estimates of place-based impacts on children’s future earnings potential and found that 64 percent of all U.S. counties that are both prosperous today and have a history of fostering economic mobility are counties with fewer than 100,000 people. As shown in Figure 2 below, more than four out of five of these counties are scattered across the Midwest and Mountain West, painting a broad swath of prosperity and upward mobility across the northern tier of the nation.

Counties that are both prosperous and foster upward mobility for poor kids. Source: EIG’s analysis of Distressed Communities Index and Equality of Opportunity Project Data.

These places have unique histories, strong social capital, and a deeply ingrained culture of work. Unemployment rates in the region are some of the lowest and labor force participation rates some of the highest nationwide. On average, 92 percent of the adult population has completed high school in these counties (compared to 86 percent nationwide), and only 35 percent of the over-16 population (which includes retirees) is not working (compared to 42 percent nationwide). Approximately 75 percent of children in these counties are raised in traditional married two-parent households. These counties (prosperous, upwardly mobile, and in the Midwest or Mountain West) are far less diverse than the country as a whole, however, with average minority populations of only 9 percent. (15)

At the same time, another large swath of rural America is a land of missing opportunity and of perpetual, persistent poverty. An astonishing 98 percent of counties that are both economically distressed and have a history of dragging down children’s future earnings potential are small counties, and of those, 85 percent are located in the South. In these counties, nearly a quarter of adults have not graduated high school and 55 percent of the adult population (everyone over 16) is not working. Approximately 44 percent of children in these counties grow up in non-traditional family arrangements. (16)

A Challenging Recovery

The Great Recession and the subsequent uneven recovery were unkind to small and rural counties. Nationally, a dismal 59 percent of U.S. counties saw more business establishments close than open during the first five years of the national recovery. (17) But in small counties, it was even higher at 64 percent. Likewise, 36 percent of counties under 100,000 residents saw employment declines over the same period, versus 31 percent of all U.S. counties. (18) Population shifts are also a factor, as 63 percent of small counties saw a net loss of population during the recovery. (19) In spite of broader national growth, more than one in five small counties experienced a net loss in all three categories: business establishments, employment, and population. On the other hand, 21 percent of small counties still managed to match the national establishment growth rate. These counties could be found throughout the country, from North Dakota to West Virginia, underscoring the resilience of many rural counties in bucking broader trends. (20)

The current recovery period also seems to have cemented a rather dramatic reversal of fortune in favor of densely populated areas in the distribution of job and business establishments. As recently as the mid-1990s, small counties led the nation in the rates of establishment and employment growth, while large counties posted the lowest rates in both categories. EIG’s research shows that patterns of economic growth now strongly favor large urban counties, which is demonstrated in Figures 3 through 5 below. (21)

The regional reversal is especially stark when considering small counties’ share of national net growth in business establishments. From 1992 to 1996, nearly one third of the net growth in U.S. establishments was housed in counties with under 100,000 residents. By the 2010s, these counties, which had once been such a promising engine of business growth, actually saw a net decline in their total number of establishments. Meanwhile, the counties with over one million in population had seen their share of net establishment growth go from 13 percent to a whopping 58 percent. (22)

Two Key Divergences: Education Attainment and the Services Economy

The present reality of rural economies diverges starkly from the trajectory of the U.S. economy in two deeply important ways that will impact the future of rural entrepreneurship and access to opportunity.

The first divergence is that educational attainment in rural areas badly lags the rest of the country. In an economy increasingly defined by “knowledge” work and cognitive skills, this limits opportunities from the individual perspective but also undermines the ability of firms or industries to locate operations in rural areas. In short, the education gap makes it harder for rural individuals to obtain jobs and harder for companies to consider rural locations.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of this trend. Recent research presents a bleak and somewhat stunning picture of economic and social malaise for Americans, notably white Americans, of lower education attainment. Mortality itself is rising within that group. (26)

The second and related divergence is that one of the largest, fastest growing, and highest paying sectors in the economy — business services — is extremely urbanized, much more so than manufacturing. Rural areas are home to 13 percent of all U.S. employment and 19 percent of all manufacturing employment but only 6 percent of all jobs in the information and professional, scientific, and technical services sectors. (27) These “knowledge economy” industries thrive in urban environments with deep talent pools and high levels of connectivity. The story of diverging economic performance is rooted in the concentration of this sector in particular.

The undersized rural services sector underscores why increasing connectivity is so important: to increase the number of potential customers and clients rural entrepreneurs can reach. The policy question is how to reduce the barriers facing rural individuals to tapping into opportunities in this growing, future-oriented sector.

Rural Entrepreneurship and Economic Dynamism

Before looking specifically at rural entrepreneurship, let’s take a moment to consider the national picture. Since the onset of the Great Recession, the United States has experienced a rapid and persistent collapse in the rate of firm formation (the “startup rate”). The national drop in startup activity is at the heart of a broader decline of economic dynamism that extends to historically low rates of labor market fluidity and geographic mobility among American workers, rapid market consolidation and growing advantages for large incumbents in most industries, and steep differences in the distribution of new jobs and businesses between regions.

The startup slowdown

These national trends harbor troubling signs for rural regions. The slowdown in new firm formation started earlier and has been more severe in rural areas than in non-rural economies.

Rural economies today are simply experiencing less change than metropolitan economies and producing fewer new “shots on goal” — new companies. With that comes reduced flexibility, less resiliency, and fewer new enterprises experimenting with new business models and taking new risks. Rural entrepreneurship is an absolute prerequisite for rural economic adaptation and for ensuring that rural areas find new lives in an ever-changing global economy.

The state of economic dynamism in rural areas

EIG has conducted a significant amount of research into what makes a dynamic, entrepreneurial economy. Density certainly fosters dynamism, but the ingredients of a dynamic local economy are not confined to urban areas.

Dynamism starts with entrepreneurship but extends much more widely to encompass individuals migrating to economic opportunity, workers moving into more productive work arrangements, and markets remaining competitive. Forthcoming research from EIG finds that dynamism trends across states tend to hold over long periods of time, making inertia difficult to reverse. Population growth in particular provides substantial fuel for economic dynamism; places without it face an uphill — but by no means impossible — climb.

Several rural states suffer neither from exceptionally low startup rates nor from exceptionally high firm closure rates. Instead, it is the gap between the two rates locally that signals a dynamism problem — notably in West Virginia, Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, New Hampshire, and Iowa. (30) With already relatively low rates of firm closures, boosting the firm creation rate is required to make sure these economies remain “above water” when it comes to entrepreneurship and the economic opportunity and local dynamism it fosters.

Another measure of economic dynamism is the share of a state’s workforce employed in firms less than one year old. Here the Dakotas, both among the 10 most rural states, land in the top 10 for jobs in new companies, too. Wyoming is not far behind in terms of startup jobs and ranks in the top 10 nationwide in terms of both net in-migration and the rate at which workers turn over among firms, an important metric of economic resilience and input into productivity growth. Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho all have among the smallest shares of their population employed in old incumbent firms, suggesting that their economies are relatively young — and incumbent interests perhaps features less prominently on the economic (and therefore political) landscape.

At the end of the day, high rates of labor force participation signal an economy that’s working well and working for working people. The top 10 states in terms of employed persons per share of the adult population are: North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Utah, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Vermont.

In general, rurality seems to be most disadvantageous when it comes to population growth (absent an economic boom such as drilling in the Dakotas) and in the sheer volume of turnover among companies — both openings and closings combined.

The mentality of self-help and initiative found in many rural areas is inherently entrepreneurial. We need to harness that energy and those natural inclinations to make sure that viable enterprises can start and scale wherever someone wants to try.

The Changing Face of Entrepreneurship

Much has been made of the potential of the Internet to provide rural areas with a new lease on economic life. While the Census Bureau’s statistics on “non-employer businesses” (which capture sole proprietors and other independent workers) shows steady growth in urban areas but no real uptick in rural ones, evidence can be found elsewhere that the so-called “platform-enabled gig economy” has indeed opened up new avenues for entrepreneurial activity in rural America (provided a fast Internet connection is available, of course). As the expansion of traditional firms and business establishments has stalled in small counties, platform-enabled entrepreneurship is on the rise.

The nature of entrepreneurial behavior in rural areas is inherently different than more densely populated areas, but the penchant often runs deep. In certain rural areas, especially in the plains, self-employment and multiple job-holding already run high. (35) Taking advantage of the reach and scale enabled by web-based platforms should be a natural step. However, the rise in platform-enabled opportunities, while welcome, is not likely to provide an ample substitute for a missing generation of new firms in much of rural America. This is because new firms have a greater impact in terms of hiring, innovation, and a host of other economic activities.

Looking to the Future: What is a “connected” rural economy?

As mentioned at the outset, highly-connected local economies are those best positioned to thrive in the new economy. The most important economic divide today is not between urban and rural but rather between connected and isolated. For example, Headwaters Economics, a research organization based in the Mountain West, classifies western counties according to three categories: those that are metropolitan, those that are rural but connected via daily air service to a larger hub, and those that are rural and isolated. Rural but connected economies have higher median incomes, lower income volatility, more high-wage service jobs, lower median ages, higher population growth, and greater educational attainment than their isolated peers. (36)

Thus, policymakers should be focused on policies that help to strengthen and expand connectivity in all its different forms for rural communities. Modernizing and repairing U.S. infrastructure is one obvious example. So too is ensuring rural entrepreneurs have better access to capital, especially via new platforms like crowdfunding and smart regional incentives that avoid hollowing out the local tax base. Another priority should be closing the “digital divide” between urban and rural areas: 39 percent of rural Americans lack access to broadband compared to only 4 percent of urban Americans. (37)

Access to global markets is another key element of connectivity. Trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) support millions of American jobs, including a great many in rural and small town communities. (38) These “insourcing” jobs tend to be higher-paying and disproportionately linked to manufacturing and innovation — in other words, exactly the kind of jobs rural communities need. In Alabama, for example, over 80 percent of all jobs in foreign-owned establishments are located outside of the Birmingham metropolitan area. (39)

Connectivity extends to human capital, as well. Physical and digital infrastructure support flows of people and ideas, but cognitive openness is important too. Workers need skills that are up-to-date and in-demand. Entrepreneurs need to be plugged in to broader market trends. Workers need to be unencumbered in their ability to move to areas of greater economic opportunity — urban as well as rural. Community colleges and workforce training programs need to support life-long learning. Universities, embedded in national and global knowledge networks, will be linchpins of local economic development efforts. The economy is evolving in directions that demand more human capital; rural areas have significant ground to make up if they hope to thrive.

Conclusion

People are generally quite bad at predicting the future. This includes, unfortunately, policy experts. For example, leading thinkers in the postwar period were actually worried about what they believed to be a looming crisis of too much leisure time as the need for long work hours diminished. In 1959 the Harvard Business Review bemoaned that “boredom, which used to bother only aristocrats, had become a common curse.” (40) Few today would say too much leisure is a defining characteristic of American life. More recently, the rise of the Internet was supposed to flatten the world and make location irrelevant; instead, the relationship between geography and opportunity appears more profound than ever.

These examples illustrate a fundamental truth: we don’t know what the world of the future will look like. Rather than trying to predict or prescribe the economy of the future, our goal should be to ensure the broader economy remains as flexible, dynamic, and adaptable as possible. Rural communities no doubt face challenges — most importantly, the challenge of adapting to an economy that increasingly rewards density and knowledge-based industries. It is important not to overstate or misinterpret those challenges. Rural communities also often have advantages that can help level the playing field, including quality of life, affordable and available land, access to natural resources, and strong social cohesion. Matching those local advantages with a national policy environment that promotes connectivity is essential. There is no substitute, however, for local leadership or local solutions. Therefore, an element of caution is needed when considering place-based federal solutions. When designed well, they can be of tremendous benefit. But even the best place-based policies will be of limited use absent a broad-based, pro-growth policy framework. In crafting such an agenda, we must avoid and eliminate policies that — even when well intentioned — tilt the balance too far in favor of guarantees versus opportunities; incumbents versus upstarts; today’s jobs versus tomorrow’s; or certainty versus healthy risk-taking.

Thank you and I look forward to answering your questions.

Citations

Small Business | Distressed Communities Index (DCI) | Geographic Trends

Related Posts

Bipartisan Call to Strengthen America’s Economic Statistical System

The Impact of Opportunity Zones on Housing Supply

Heartland Visas: A Policy Primer