By Connor O’Brien

Key Findings

- Deaths from COVID-19, declining birth rates, and a dramatic slowdown in international migration combined to make 2021 the slowest year for population growth in American history, according to new data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

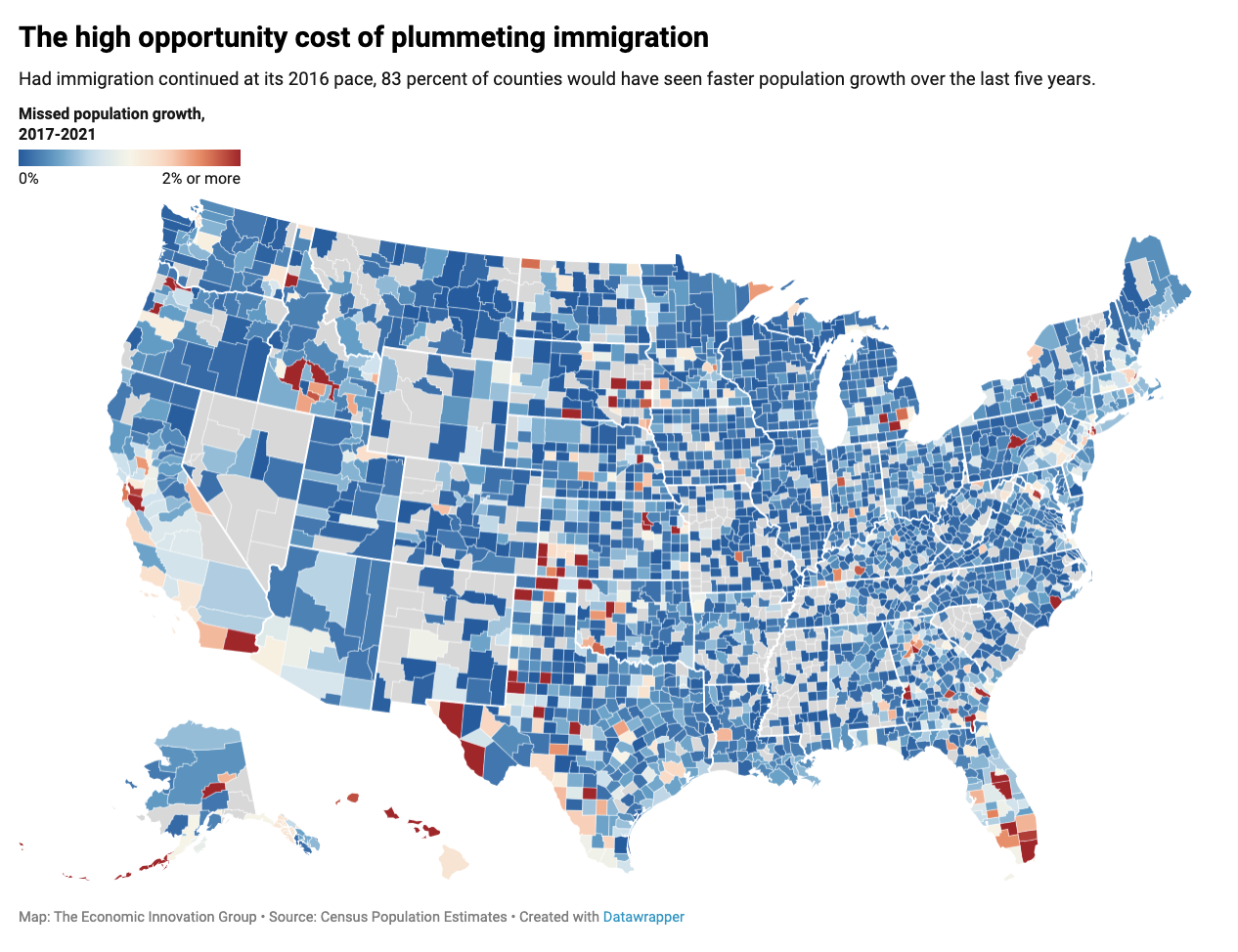

- Forty-two percent of all counties in the United States lost residents between July 1, 2020 and July 1, 2021. The swift decline in immigration since 2016 has further accelerated demographic decline across the country—had immigration kept up with its 2016 pace, the overall U.S. population would be nearly 2 million residents larger.

- Many small, rural counties in the Midwest and South were hit hard by the decline in immigration.

- Dozens of counties—ranging from big cities like Miami to agricultural communities in Nebraska—shrank between 2016 and 2021, but would have grown had immigration kept pace.

- Immigration reforms like EIG’s Heartland Visa program can help reverse stubborn population decline and its associated consequences in heartland communities and elsewhere.

Introduction

Like many countries across the developed world, the United States is experiencing declining population growth. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising “deaths of despair,” falling birthrates, and plummeting international migration combined to make 2021 the slowest year for population growth in American history at just 0.1 percent. While many factors have contributed, the sudden and enormous decline in international migration has been the largest disruption to population growth over the last decade. Net international migration in 2021 was down 66 percent from 2016, to just 505,000 net new arrivals.

Falling immigration has served many communities a demographic double-whammy at a time when communities can least afford it. Nationally, these forces are a drag on economic growth, technological progress, and perhaps even geopolitical standing. But for many Americans, the most acute effects are local. A shrinking, aging population means a smaller tax base for schools and infrastructure projects, fewer entrepreneurs, and less vibrant downtowns as service and hospitality sectors struggle to survive with a narrower customer base.

Thankfully, declining immigration is also the most easily-reversible force inhibiting growth in America.

The decline of international migration has been very large and sudden.

The most recent peak in net international migration to the United States took place in 2016, when the country admitted 1.47 million new arrivals. Net arrivals gradually fell in ensuing years despite a rise in asylum-seekers. The pandemic dramatically slowed immigration around the world, and the United States was no exception. Admissions fell to under one million in 2020, and further to 505,000 in 2021.

x

x

Falling immigration is thus a major contributor to the outright population decline facing much of the country. By 2021, 47 percent of counties in the United States had smaller populations than they did in 2016, and 52 percent have fewer residents than they did in 2010.

The share of counties shrinking fell in 2021, but this is unlikely to continue.

Roughly 42 percent of counties in the United States saw their populations decline last year. While this figure is down substantially from 2020 and prior years—when approximately half of all counties shrank year-to-year—this year’s reversal is chiefly a result of domestic migration out of very large metro areas spread throughout the country. There are a number of potential hypotheses for why this took place, including the shift to permanent remote or hybrid work arrangements, high urban housing costs, and changes in preferences.

Why, then, highlight widespread population decline now? First, domestic migration is by definition zero-sum. If domestic migration continues but the national population is not growing, some places will have to bear the harsh economic and social consequences of population loss. Second, the long-term remote work trajectory remains unclear. Though this trend may abate population loss on the margin in some otherwise-shrinking places, it may not provide a continuing source of migration on the scale of last year, since most easily-remotable jobs have already gone remote (although where “back to work” hybrid arrangements settle remains a major unknown). Finally, American geographic mobility hit an all-time low in 2021, so it is unlikely that the COVID pandemic jump-started a new era of large internal movement.

Both heartland communities and large cities have been hurt from declining immigration.

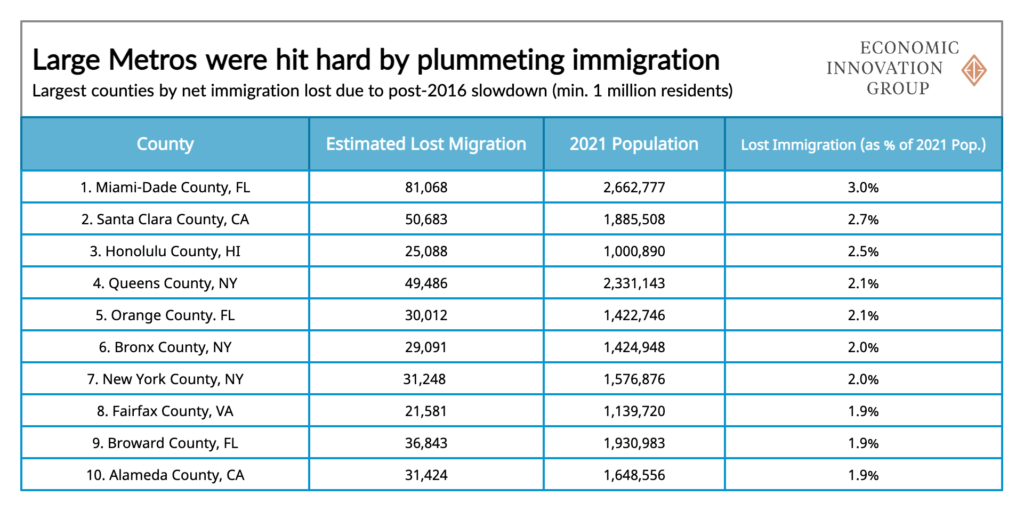

In absolute terms, coastal cities—many of which are traditional hubs for immigration—have been hit hardest by the decline in immigration since 2016. Los Angeles County added nearly 37,000 residents via international migration in 2016, which gradually fell to just around 4,000 net new residents in 2021. Had Los Angeles kept growing at its 2016 pace, it would have 114,500 more people today—a 1.2 percent increase over its actual 2021 population. Miami-Dade County would have 81,100 additional residents and New York City would have 154,300 (compared to its actual 2021 population loss of 305,000). Had the country at-large added as many net immigrants each year between 2017 and 2021 as it did in 2016, the United States would have nearly 2 million additional residents.

Historically, immigration has long been the primary source of population growth for many major metro areas. Three-quarters of the top 20 counties by 2019 population saw consistent net outward migration before the pandemic; however, a majority still saw overall net population growth because of net international migration. As immigration has fallen off, many of these areas have felt the starkest impact, tipping into outright population loss as new arrivals from abroad no longer offset domestic departures. The Bay Area in particular exemplifies this trend—Alameda County (Oakland) shrank slightly between 2016 and 2021, but would have grown 1.8 percent had immigration remained elevated. Santa Clara County (San Jose) shrank by 2.2 percent, but would have added an additional 50,700 residents—a 0.4 percent growth—between 2016 and 2021..

For 68 counties ranging from big cities to small rural counties, a loss of migrants made the difference between outright shrinking and growing. Colfax County, Nebraska—a tiny, heavily-agricultural county west of Omaha—shrank 2.1 percent between 2016 and 2021, but would have grown 1.8 percent had immigration kept up. Meanwhile, cities like Miami, San Jose, and San Diego which saw population decline over this time also would have grown. Nevertheless, most of the counties that shrank between 2016 and 2021 but would have grown otherwise were small, with about two-thirds having populations under 100,000.

In relative terms, many of the counties which have lost the most are very small and rural. Garza County, Texas, with a population of 6,197 lost out on over 150 new residents by not maintaining its 2016 pace of net immigration, a substantial loss for a county of this size. The national immigration shortfall cost this county—which has a poverty rate of over 20 percent—newcomers that might have become entrepreneurs, contributed tax receipts to the maintenance of fixed public assets like schools and roads, or supplied local business owners with labor. Other small counties throughout Georgia, Texas, Kansas, Alaska, and elsewhere are among the counties that lost out most from falling immigration. College towns across the Midwest and Northeast stand out, too, as reduced international student enrollments placed a drag on population growth in places such as Ithaca, NY; State College, PA; Bloomington, IN; and Manhattan, KS.

x

x

These are, of course, simple estimates obtained by assuming net immigration continued at 2016 levels in each county between 2017 and 2021, while natural increases (births minus deaths) and net domestic migration remain unchanged. International and domestic migration may, to some extent, be substitutes in areas with inelastic housing markets, as either would bid up the price of housing and further deter potential newcomers. However, in places that are shrinking or slow going—where housing isn't especially scarce—substitution is less likely to occur. Indeed, in a healthily functioning market, domestic and international migration would be complementary as migrants from all backgrounds seek out economic opportunity.

Conclusion

The unusual year 2021 provided some relief from the population decline that has plagued many counties over the past decade, but long-run forces are still likely to stifle growth going forward. The dramatic decline in immigration over the last five years has unnecessarily added an additional factor pushing population growth to its lowest rate since the nation’s founding. Shrinking communities need a comprehensive policy approach to avoid sharp population decline, including support for parents, policy to address the opioid epidemic, and more longshot health research to lengthen and improve the quality of elderly Americans’ lives. Immigration provides a low-cost option that could help businesses meet their need for workers, municipalities maintain their infrastructure assets, and storefront services stay open. Ideas like EIG’s Heartland Visa would provide a large economic and demographic boost to these communities at a time when they desperately need it.