Today, The Wall Street Journal ran a story examining South Bend’s economic performance under Mayor Pete Buttigieg, contender for the Democratic nomination for president. In it, they cite EIG’s analysis of the city in the context of its peers. Here we present our full analysis to see what lessons South Bend may hold for other struggling cities throughout the industrial heartland.

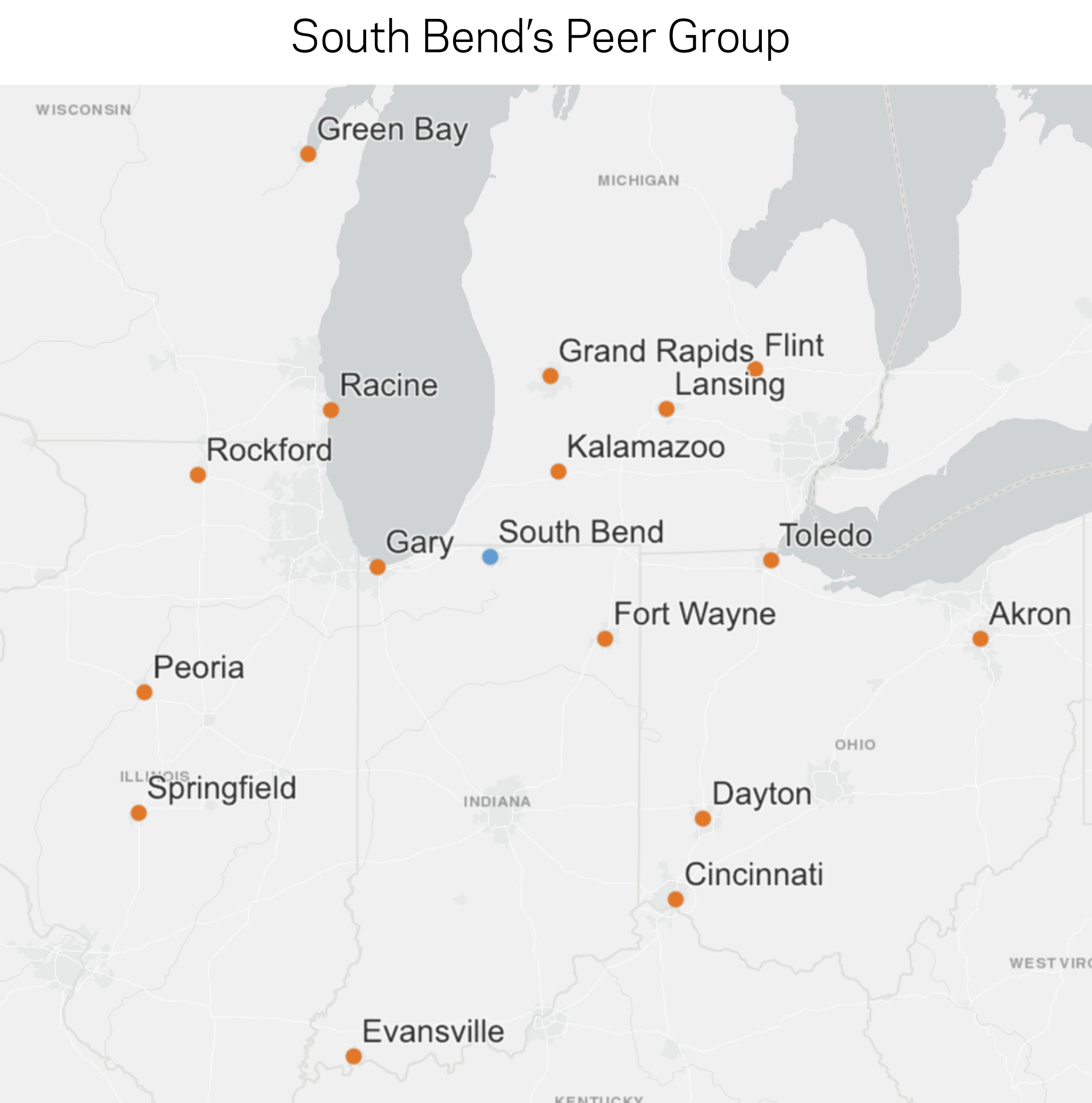

To anchor the analysis, we identified a peer group of 16 other cities across five states (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin) with a similar population to South Bend (between 75,000 and 300,000 people) and with similar local economic characteristics.

Mid-sized Great Lakes cities are in a league of their own

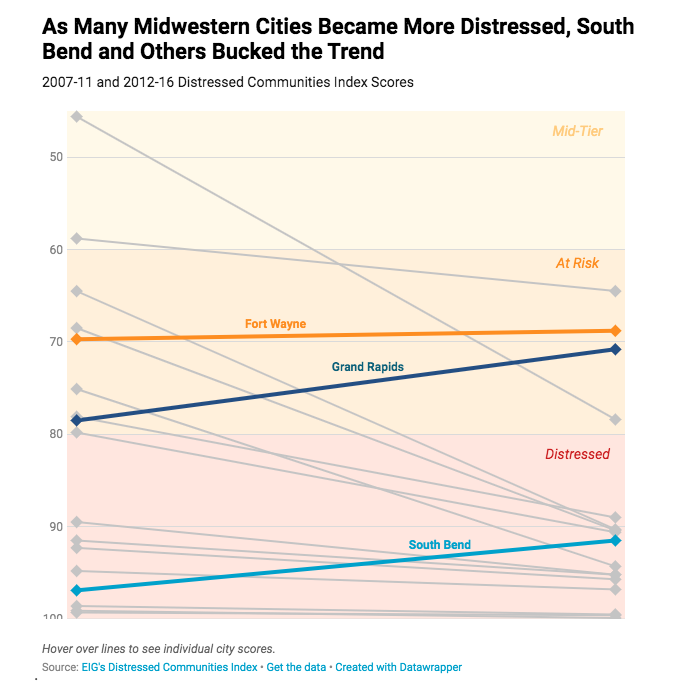

EIG’s Distressed Communities Index (DCI) provides a comparative assessment of economic well-being across 812 U.S. cities (defined as “places” by the U.S. Census Bureau) with more than 50,000 residents by ranking performance across seven different economic and social indicators. The index confirms that South Bend is a member of a highly distressed peer group. Fully 13 of the 17 cities in the cohort fell into the bottom quintile on the DCI (the “distressed” category). The remaining four cities landed into the “at risk” category, only one quintile higher. No city ranked above the sixty-fourth percentile nationally. (Scores on the DCI are equivalent with percentiles.)

Any assessment of an individual city’s performance must consider this broader context: cities of this size in this region generally bear long legacies of deindustrialization and social segregation that continue to influence their economic trajectories today. Of course, these legacies also provide unique assets: engaged anchor institutions, deep civic infrastructure, character-rich built environments, and strong senses of place. Proud histories of immigration and global engagement, not to mention solid bases of competitive employers that survived manufacturing’s tumultuous 2000s, make “Rust Belt” cities better positioned to embrace the future than they are typically given credit for. But they undeniably compete in the modern economy more encumbered than brand-new, blank-slate “Sun Belt” places, and they have weaker forces of agglomeration and renewal to fall back on than much larger metropolitan economies.

In the end, only three cities in this group improved their position in the national rankings on the DCI between the 2007-2011 and 2012-2016 periods. South Bend was one of them. Grand Rapids, MI, led the pack, climbing 7.7 points within its “at risk” bracket. South Bend followed with the second-best improvement in national position in the group. The city started off exceptionally distressed, scoring 96.9 on the index in the 2007-2011 period. It subsequently climbed 5.4 points to 91.5, which placed it solidly in the middle of both its peer group and the distressed bracket of cities nationwide. Fort Wayne, IN, rounded out the trio with a small ascent.

.

The rank of most other peer cities fell between those two time periods. What happened? In some cases, job losses persisted long after the national economy rebounded. This was true in Evansville, IN; Gary, IN; Peoria, IL; and Racine, WI. (Even South Bend continued to rack up job losses into 2012 and 2013, but a strong rebound in the subsequent years helped power its rise on the DCI). In other places, poverty rates remained elevated for longer than elsewhere, or incomes stagnated. In general, though, relative declines stem from weaker recoveries from the Great Recession than the rest of the country, not from a deterioration of conditions on the ground.

The population of some heartland cities is stabilizing

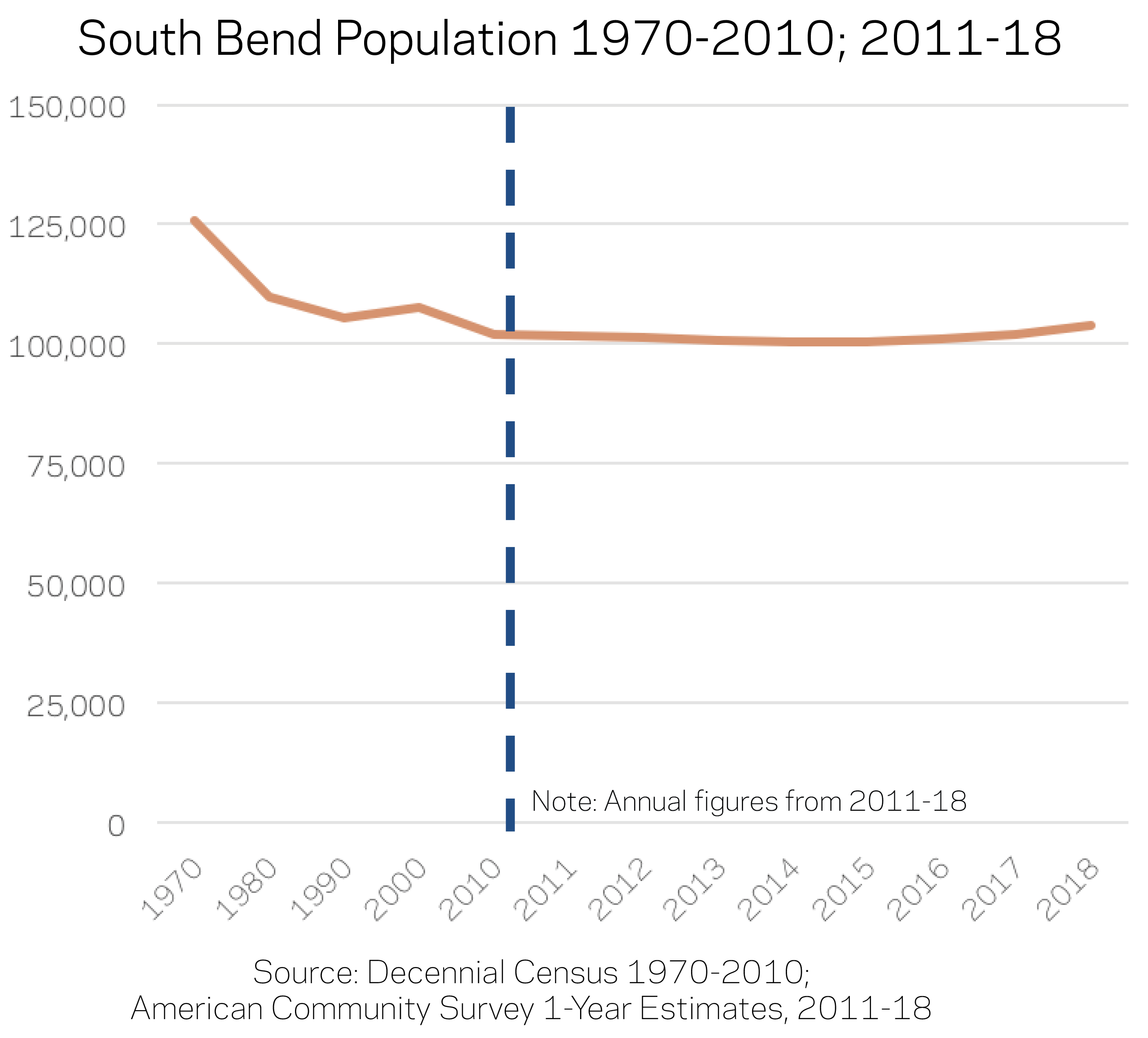

South Bend ranked second in its cohort of peer cities on population growth. Between 2011, the year Mayor Buttigieg was elected, and 2018, South Bend’s population increased by 2.7 percent, behind only Grand Rapids in the peer group. The city added nearly 3,000 residents over the period. Tellingly, South Bend’s population growth now beats surrounding St. Joseph County, which historically added residents much faster than the city.

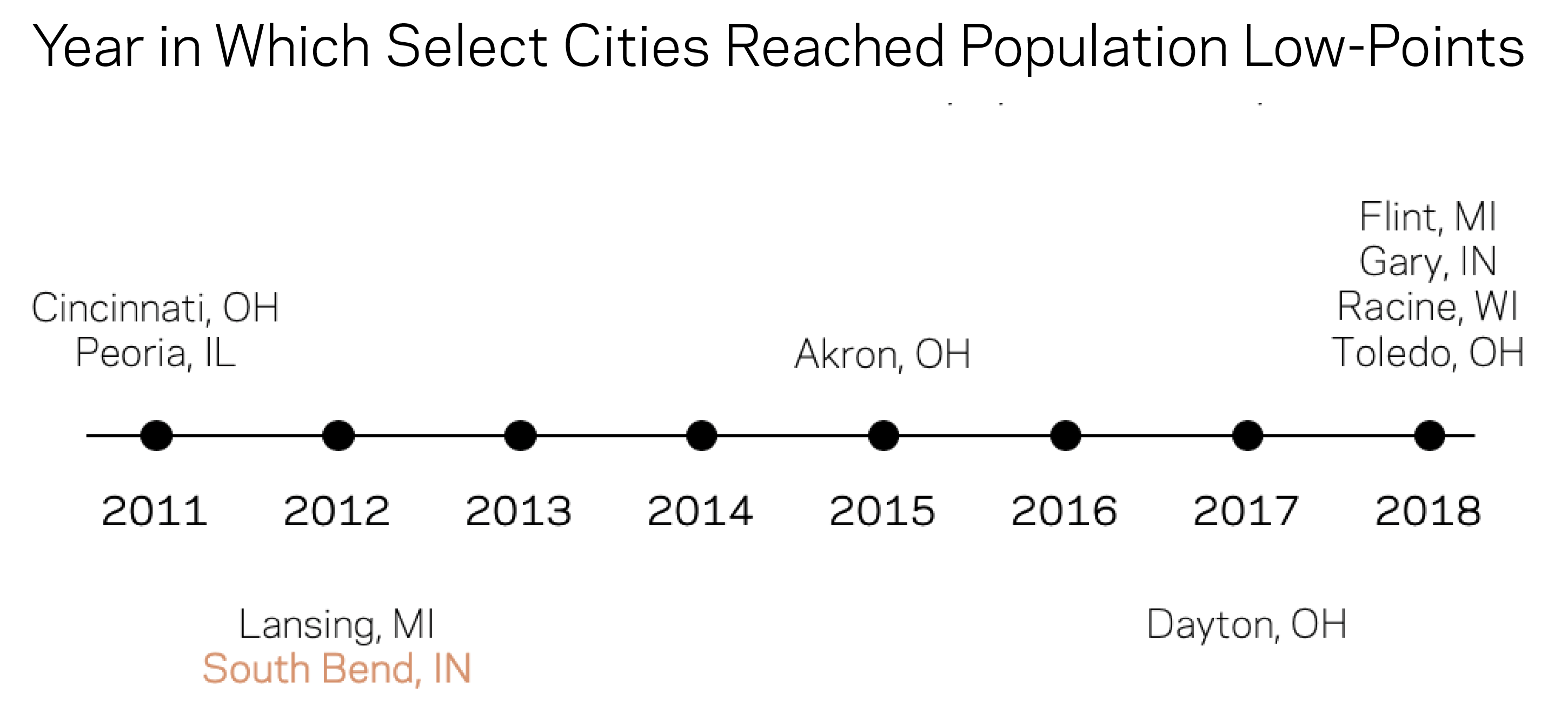

The longer trend shows that the stabilization and modest growth over which Mayor Buttigieg presided came on the heels of a long period of gradual population loss. Several peer cities are experiencing similar reprieves from decline. In the case of South Bend, from 1980 to 2011, the city lost eight percent of its population—modest compared to the 30 percent loss in Dayton, OH, or the 47 percent decline in Gary, IN, over the same time period. The presence of Notre Dame, a formidable anchor institution, may have helped stave off further losses.

After years of an eroding population, stabilization can be an inflection point. Once population loss abates, city priorities can shift from managing decline to planning for a brighter future. Tax receipts stabilize, as do neighborhoods where vacant homes find new occupants. Private investment returns. Mixed-use districts take off, attracting even more residents and spending while helping change outside perceptions about a place. Many of these features apply to South Bend during Mayor Buttigieg’s tenure.

Roughly one-third of South Bend’s peer cities found themselves turning this important corner in recent years as well. Another one-third have enjoyed slow but steady population growth or recovery over longer time horizons. The final third still struggle to stem population loss, having registered new lows in 2017 or 2018.

Unfinished business remains

In South Bend and across the region, unfinished business remains. Two areas for continued progress stand out: inclusion and incomes.

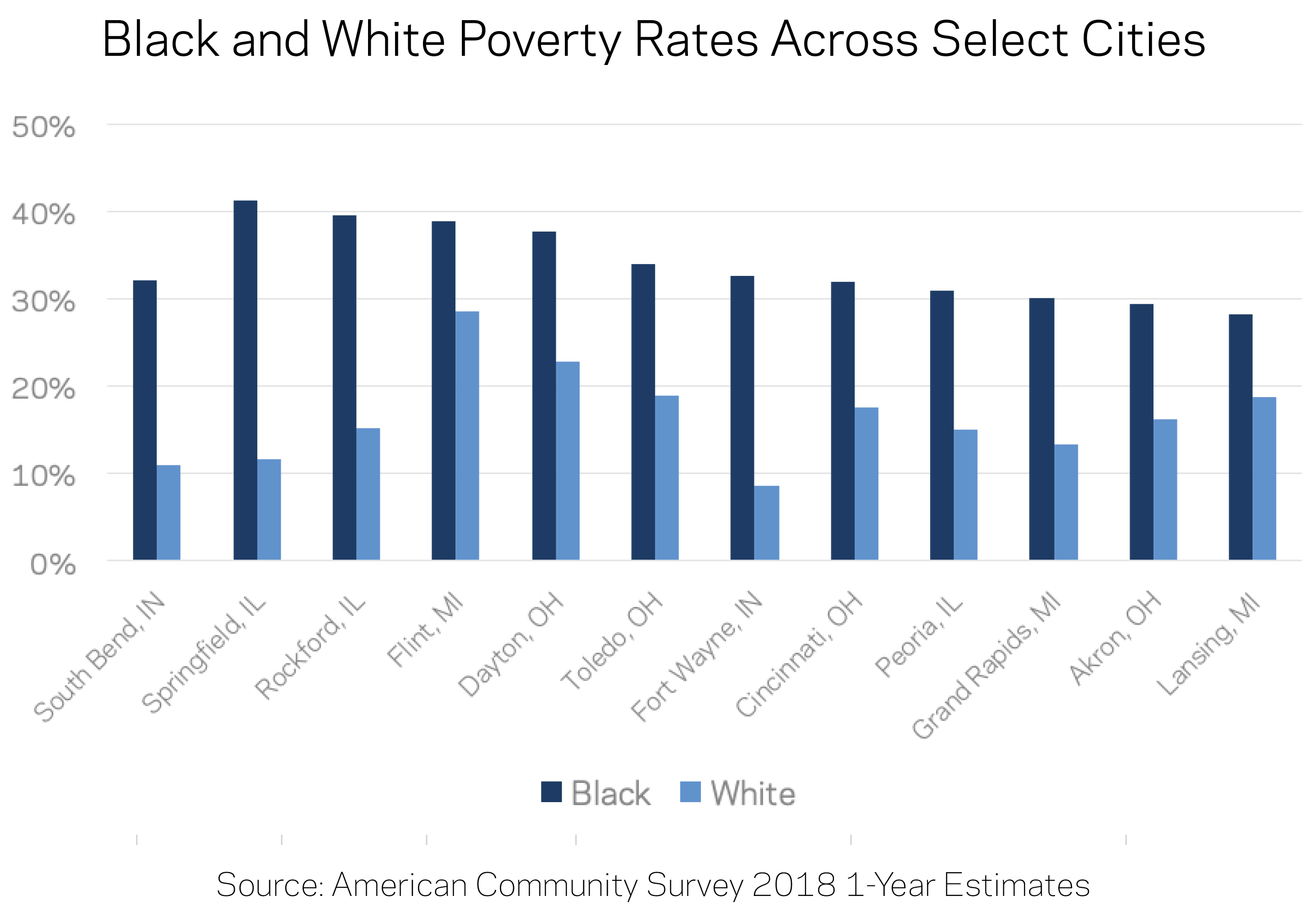

South Bend’s black poverty rate had skyrocketed to 53 percent in 2011, the year before Mayor Buttigieg took office. The figure had fallen by 20 percentage points come 2018 but remained three times higher than the white poverty rate locally. Sadly, such racial disparities are common to cities in the region. Indeed, South Bend is on par with its state and peer cities on this measure.

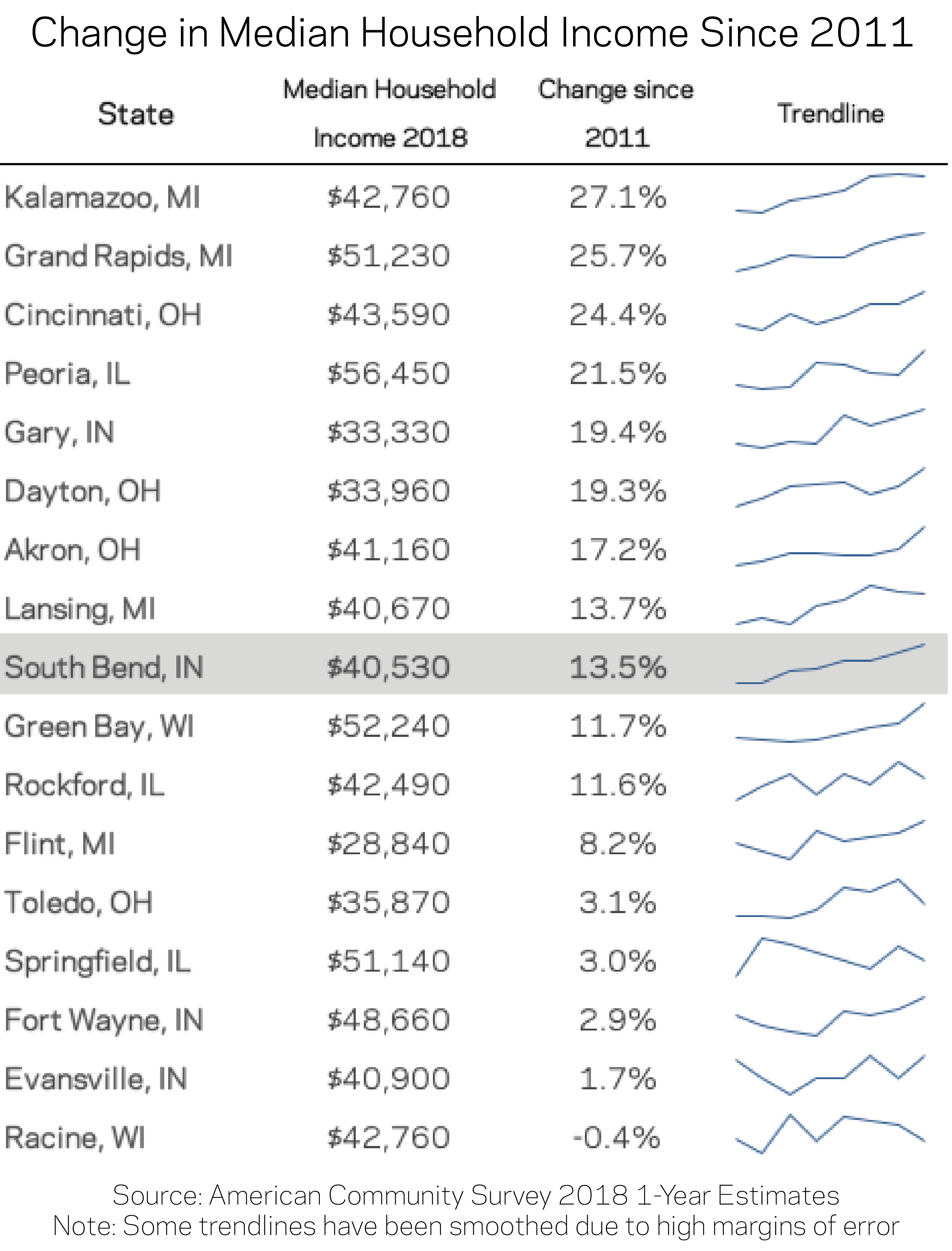

Under Mayor Buttigieg, South Bend experienced a 13.5 percent rise in median household income between 2011 and 2018—a figure that ranked in the middle of the peer group but was nearly twice the 7.3 percent rise registered statewide. Even after that advance, however, median household income in South Bend trails behind the nation, the state of Indiana, and many of the city’s peers. The typical household in South Bend earned $40,530 in 2018, $4,800 more than in 2011 but less than the median household in 12 other peer cities. Meanwhile, the statewide median household income was a more comfortable $55,750. Nationally, it stood at $61,940 in 2018—a level that none of the cohort cities even approached.

Reflections on a region in flux

The mid-sized cities of the Great Lakes now find themselves in a staggered emergence from periods of economic decline. Most remain distressed by national standards. Incomes trail significantly behind the nation as a whole. Modest recoveries from the Great Recession pale in comparison to the forceful rebounds experienced across much of the rest of the country.

The nation may yearn for stories of decline and dramatic resurgence, but the data provide a sobering reminder that the real work of restoring economic dynamism takes time. There are no quick paths to economic transformation. Building a prosperous, inclusive economy is generational work. Progress is incremental. One milestone builds on another. Today’s political timelines are deeply out of step with these local economic realities.

That does not mean that local ambitions should be reined in. Quite the contrary: ambition—often embodied in dynamic mayors—is one of the region’s strongest assets. Federal and state governments should leverage the energy building in the heartland by assembling a more robust policy toolkit to reward local engagement. Ideas such as a heartland visa, which would open new channels of immigration for welcoming cities ready to fight population loss (and which both the Buttigieg and Biden campaigns have embraced), capture the spirit of what is needed to hasten heartland revival.