TESTIMONY BEFORE THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS

JOHN W. LETTIERI, CO-FOUNDER AND PRESIDENT, ECONOMIC INNOVATION GROUP

“The Promise of Opportunity Zones”

May 17, 2018

Introduction

Chairman Paulsen, Ranking Member Heinrich, and members of the committee: it is a pleasure to be with you today.

I am the Co-founder and President of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a bipartisan research and advocacy organization. EIG helped to design and champion the Investing in Opportunity Act, legislation authored by Senators Tim Scott (R-SC) and Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Representatives Pat Tiberi (R-OH) and Ron Kind (D-WI). This legislation, which enjoyed broad bipartisan support, was the basis for the Opportunity Zones provision in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017.

The Opportunity Zones initiative is the most ambitious federal attempt to boost private investment in low-income areas in a generation, one with the potential to drive billions of dollars in new private investment to struggling communities over the coming decade. Since Opportunity Zones became law, EIG has worked closely with state and local policymakers, community organizations, philanthropies, and leading investors to raise awareness, provide analysis, and gather feedback in support of timely and effective implementation nationwide.

In the testimony that follows, I will:

- Highlight key design features of the Opportunity Zones incentive;

- Provide an overview and analysis of the state selection process and outcomes;

- Underscore what states, cities, and the federal government should do to make Opportunity Zones successful; and,

- Address ways to define and measure success.

Key features of the Opportunity Zones incentive

The fundamental purpose of Opportunity Zones is to encourage long-term equity investments in struggling communities. In pursuing this goal, Congress established an incentive framework flexible enough to support a broad array of investments and encourage creative local implementation strategies. The unique structure – and equity focus – of this incentive has the potential to unlock an entirely new category of investors and create an important new asset class of investments. Congress designed Opportunity Zones to complement existing community development programs while incorporating lessons learned from previous place-based efforts. I want to draw particular attention to two of its most important distinguishing features:

- First, it is a highly flexible incentive that can be used to fund an array of equity investments in a variety of different sectors. This is critical, because low-income communities have a wide range of needs, and Opportunity Zones at their best will recruit investments in a variety of mutually enforcing enterprises that together improve the equilibrium of the local community. The structural flexibility extends to Opportunity Funds, the intermediaries that raise and deploy capital into Opportunity Zones. These funds can be nimble in responding to market interest and opportunity, thereby widening the aperture of investors who can participate. And, because Opportunity Funds do not need pre-approval for transactions, the cost, complexity, and time needed to deploy capital should be lower than in other programs.

- Second, the incentive is nationally scalable. There is no fixed cap on the amount on capital that can be channeled to target communities via Opportunity Funds, nor is there a limit on the number of Opportunity Zones that can receive investments in any given year. This scalability derives from that fact that investors are incented to reinvest their own capital gains without any up-front subsidy or allocation. EIG’s analysis of Federal Reserve data found an estimated $6.1 trillion dollars in unrealized capital gains held by U.S. households and corporations as of the end of 2017. Even a small fraction of these gains reinvested into Opportunity Zones would make it the largest economic development initiative in the country.

Flexibility and scalability are essential ingredients because they unlock the vast creativity and problem-solving potential of communities and the marketplace in ways that would not be possible under a more prescriptive policy framework. Congress and the Administration should do everything possible to preserve and enhance these features as implementation moves forward in the months ahead, including through technical statutory refinements that will help ensure strong uptake among a broad spectrum of investors.

How were Opportunity Zones selected?

Congress gave governors of every state and territory the critical lead role of selecting Opportunity Zones. Under the statute, each governor was allowed nominate up to 25 percent of his or her state’s low-income community census tracts to be designated as areas where the federal tax incentive will apply.

Low-income community census tracts are generally defined as places with poverty rates of at least 20 percent or median family incomes no greater than 80 percent of the surrounding area. Nearly 32,000 tracts meet this definition nationwide, totaling roughly 43 percent of all U.S. census tracts. Thus, governors had to narrow the pool of eligible tracts down to roughly 8,700 selections. In order to offer real-world flexibility in assembling meaningful zones, governors were permitted to substitute up to 5 percent of their nominated tracts with those that met a slightly lower need threshold, as long as the tracts were contiguous with other nominated low-income community tracts. Governors were required to submit their nominations to the U.S. Department of the Treasury by April 20, and we now await the final tranche of certifications by the Secretary to complete the national map.

Congress sought to establish a national standard for Opportunity Zones while allowing local priorities to dictate the target communities. The resulting selection process was in keeping with the federalist spirit of the new law, as states went about identifying priorities, engaging stakeholders, and incorporating additional selection criteria in ways that reflected their unique local characteristics. The core challenge for governors was striking the right balance between need and opportunity. In response, they sought to identify highly distressed communities that demonstrated an absorptive capacity for new capital, strong anchor institutions, and connectivity to infrastructure and markets.

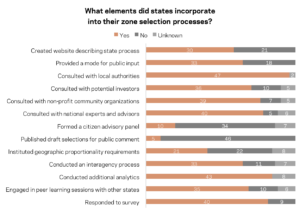

EIG recently surveyed state officials involved in designating Opportunity Zones. We have combined responses from 40 states with additional insights gleaned from conversations and online resources to build a thorough understanding of how states selected their zones.

States consulted heavily with their municipalities, counties, and local and regional economic development organizations to assemble their portfolios of Opportunity Zones. It appears that every state augmented the federal eligibility criteria with additional data analytics. Some, such as Colorado, Oregon, and Illinois developed sophisticated tools in-house while others, like Wisconsin and New Jersey, engaged outside experts to help identify optimal sets of tracts. Roughly half of states sought to distribute zones proportionally among eligible counties or municipalities. Some, like Michigan and New York, particularly emphasized aligning Opportunity Zones with existing programs and investments.

States approached their designations with a variety of outcomes in mind. Several prioritized boosting entrepreneurship and new business formation. Colorado, for example, intends to combine Opportunity Zones with other state efforts to stimulate entrepreneurship and innovation in rural communities. Virginia partnered with the University of Virginia to develop an “Entrepreneurship Readiness Index” to identify low-income communities with strong human capital or entrepreneur support programs that were perhaps lacking in access to capital for startups—a gap Opportunity Zones is well-positioned to fill.

Other governors anchored their Opportunity Zone nominations around existing strategies for revitalizing historic downtowns and city centers. In Massachusetts, this meant that almost half of their Opportunity Zones are in the state’s “Gateway Cities,” midsize urban centers that anchor regional economies but have recently struggled to draw new investment. Vermont recognized an opportunity to revitalize its small town centers – vital community anchors in a relatively rural state. In fact numerous states embraced Opportunity Zones as a promising new lifeline for their rural communities. New Jersey emphasized access to transit, an important strategy for connecting workers to jobs, evident in the fact that nearly two-thirds of its Opportunity Zones are within half a mile of a transit station. Interagency working groups were common, such as Minnesota’s effort to harness Opportunity Zones to upgrade and build new affordable workforce housing.

States also found many different ways to solicit public engagement. At least 34 states stood up a public comment portal for input. Some worked more closely with municipalities, giving them final approval. Indiana used an external advisory panel – comprised of representatives from community development and social services nonprofits, the Indiana Farm Bureau, and a former mayor – to vet selections alongside the governor’s office and state agencies. Five states published their draft maps before submitting to Treasury for the public to weigh in. In the case of California, this led to the revision of fully one-fifth of its tracts before submission to Treasury.

There is no doubt that the passage of Opportunity Zones has already generated tremendous local interest and coordination across a variety of sectors. While we are still early in the implementation process, the high degree of engagement nationwide is itself an early milestone of success for this fledgling effort.

Now let’s examine the selected tracts in greater detail.

What are the characteristics of the typical Opportunity Zone?

As of this hearing, EIG has been able to collect and analyze census tract-level Opportunity Zones data from 42 states representing 87 percent of the national total to be designated – a large enough sample size to draw general conclusions about Opportunity Zones as a geographic asset class.[1]

- Demographics: Tracts selected thus far are home to more than 27 million people, 57 percent of whom are non-white (compared to 53 percent of the population in all low-income communities). States took special care to include tribal groups in their selections: 250 tracts contain American Indian Areas, and several states included explicit set-asides to ensure their inclusion.

- Neighborhood Change: Some observers raised concerns over the possibility that governors would simply target already gentrifying areas. However, less than four percent of selected census tracts have experienced high levels of socioeconomic change from 2000 to 2016, according to a dataset developed by the Urban Institute. In fact, the average Opportunity Zone’s housing stock has a median age of 50 years, more than ten years older than the U.S. median. As we will see below, the economic characteristics of selected areas do not lend themselves to widespread concern over gentrification or displacement of local residents.

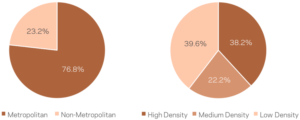

- Population Density:23 percent of the tracts lie outside of a metropolitan area, making them slightly more rural than the low-income communities as a whole. In terms of the zip code in which tracts lie, Opportunity Zones are nearly evenly split at 38 percent in high density (urban) areas and 40 percent in low density (rural) ones, with the remainder located in medium density (suburban) communities.

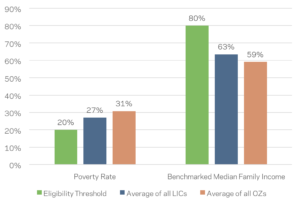

- Poverty Rate:The designated tracts have an average poverty rate of nearly 31 percent – well above the 20 percent eligibility threshold and nearly four points higher than all low-income communities as a whole. Even when adjusting for areas with high populations of college students that can sometimes skew data, selected tracts still show an average poverty rate of 30 percent.

- Median Family Income: Median family incomes also show that the selected tracts skew toward places of higher need: The average Opportunity Zone has a median family income equal to only 59 percent of its area median – significantly lower than the 80 percent eligibility threshold.

- Severely Distressed Areas: Fully 69 percent of the population in Opportunity Zones resides in a census tract that is considered “severely distressed,” generally defined by the Treasury’s CDFI Fund as places that have poverty rates of at least 30 percent, unemployment rates at least 1.5 times the national rate, or median family incomes lower than 60 percent of the area median. More than 95 percent of Florida’s 427 nominated tracts qualify as severely distressed.

- Adults Not Working: In the average selected tract, 38 percent of the prime age population is not working – nearly 10 points higher than the U.S. as a whole.

Governors clearly went beyond the statutory threshold for targeting high-need communities in their zone designations. But how did they do in identifying areas of opportunity? Here again, there is evidence that governors struck a thoughtful balance. 76 percent of selected tracts are located within zip codes that experienced at least some level of employment growth from 2011 to 2015,[2] and 66 percent of selected tracts are in zip codes with an increased number of business establishments over the same period.

What should states and cities do to make Opportunity Zones successful?

There is a reason this policy is called “Opportunity Zones” instead of “Guarantee Zones.” While Opportunity Zones is a federal incentive, its success in any given community will ultimately depend on state and local leadership.

First and foremost, every state needs a strategy to ensure strong coordination between the public, private, and philanthropic sectors. Some areas are naturally better positioned to attract and absorb investment than others. Areas with fewer advantages – particularly non-metropolitan rural areas – may require greater engagement from the public and philanthropic sectors to see long-term success. Educational institutions, community organizations, foundations, major local employers, small business support centers – all of these and more must be recruited into a coordinated effort to build local capacity. And since most equity investors are disconnected from low-income communities, local leaders must be especially proactive in ensuring investors are aware of local assets, partners, and opportunities. This is an area where collaboration with the philanthropic sector could be particularly meaningful.

Governors should ensure their state tax codes conform with the Opportunity Zones incentive so as not to disadvantage local investors and communities (as New York has already done). And while private investment is a key ingredient of any healthy economy, capital incentives alone can only achieve limited results. States should work to align workforce development programs to help local residents take advantage of new employment opportunities, ease restrictive land use regulations that prevent inclusive growth, and reduce onerous occupational licensing burdens. And every governor should ensure strong accountability and coordination by designating a senior official as the point person for Opportunity Zones.

Lastly, since Opportunity Funds are the essential intermediary in connecting the capital and the communities, some public sector entities may want to establish their own funds dedicated to serving specific localities or pursuing certain policy objectives. I believe such public-private models will become a key part of the broader ecosystem in many local markets.

Next steps for Congress and the Administration

Congress and the Administration should look for creative ways to enhance the success of Opportunity Zones, but two immediate issues come to mind. First, as Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service moves forward with implementation in the coming months, Congress should move quickly to address a small number of key statutory technical corrections necessary to making Opportunity Zones work as originally intended. Among these are issues related to the time Opportunity Funds have to deploy capital into the zones, the ability to recycle capital returned to a fund back into Opportunity Zones without penalty to its investors, and the manner in which certain definitions are applied in the statute. Delaying or failing to enact such corrections will inhibit investor uptake and limit the scale of impact in communities. Second, in addition to timely implementation by Treasury, I urge the President to pursue an aggressive interagency effort to ensure every relevant agency is made accountable to support the needs of Opportunity Zones communities in measurable ways (e.g., SBA loan guarantees, EPA brownfield cleanup funding, EDA grants, etc.), particularly in identifying and rewarding state and local best practices that can serve as models for other communities nationwide.

How should we measure and define success?

Every community has different needs, assets, and challenges. Just as it would be wrong to impose a one-size-fits-all approach to how the Opportunity Zones incentive should be put to local use, it would also be wrong to evaluate every community against the same metrics. Given the flexibility and scalability I mentioned earlier, one national measure of success is in the variety of positive outcomes achieved over time. If Opportunity Zones works as intended, we should see a vibrant ecosystem of Opportunity Funds created – from large national funds, to small and middle market funds focused on specific regions, to sector-specific funds, and so on. Additionally, we should see those funds helping communities tackle a wide range of issues, including revitalizing downtown districts, boosting local entrepreneurship, establishing specialized funds to target rural development challenges, commercializing technology around local knowledge centers, and more. I believe this incentive could be particularly impactful in “second tier” cities, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast, where the need for property improvements and business creation is high, and where we often see entire contiguous downtown areas designated as Opportunity Zones.

Above all, the core measure of success is whether Opportunity Zones establishes a stronger and broader connectivity between communities and the equity capital needed to seed new industries, revitalize local assets, fuel innovation, and improve access to opportunity.

While the scale of potential impact is enormous, I want to underscore that the Opportunity Zones incentive is not the solution for every local financing need, let alone every broader issue facing low-income communities. Opportunity Zones provides a tool – potentially a very powerful one – but it is not a panacea. We must keep sight of the fact that reviving struggling communities is a long-term, complex undertaking. That is why measurement and transparency are key. States should be proactive in making data about their Opportunity Zones available to investors, researchers, and the general public. Every state should create an online portal where information on local priorities, qualified investments, and complementary state and local programs can be found. Additionally, in the conference report accompanying the TCJA, Congress outlined a worthy framework for Treasury to use in tracking and evaluating Opportunity Zones investment activity and its impact in local communities. Such data would help researchers and policymakers better understand how to iterate and improve incentive models and local strategies in the future.

Conclusion

When I testified before this committee last year on ways to boost economic opportunity in the United States, I urged Congress to take a more ambitious and experimental approach to tackling complicated issues. It is exciting to be here a year later as the country embarks on the implementation of Opportunity Zones, which is already bringing new energy, ideas, and much-needed attention to one of the nation’s most vexing challenges. The past economic development toolkit clearly has not worked for the tens of millions of Americans living in communities where the American Dream feels unattainable. Congress has responded with a bold new idea. You placed confidence in governors, in mayors, in community organizations, in investors and entrepreneurs to come together in support of people and places our economy has left behind. This is, indeed, a rare opportunity to lift thousands of communities and improve millions of lives. But the work is just beginning. I urge you to remain committed to the task of making Opportunity Zones a success.

Thank you, and I look forward to answering your questions.

[1] This analysis excludes data from U.S. territories in order to focus exclusively on the 50 states plus the District of Columbia. Were the territories included, indicators of need within selected tracts would have been even higher.

[2] As of the time of drafting, 2015 was the most recent year for which zip code level data was available from the U.S. Census Bureau.