By August Benzow, Kenan Fikri, and Daniel Newman

Introduction

The Phase IV Small Business Relief Package introduced by Senators Marco Rubio and Susan Collins this week contains a new long-term lending facility, the “Recovery Sector Loan Program,” that would extend a financial lifeline to many of the country’s beleaguered small businesses. Importantly, and in both complement and contrast to other proposals such as extending the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the new proposal has the potential to help businesses emerge from the pandemic not just intact but stronger and in a better position to drive the economic recovery.

Senators Rubio and Collins propose revising the well-known 7(a) small business loan program to allow for the creation of new small business Recovery Sector Loans with extremely favorable terms for qualified borrowers experiencing dramatic shortfalls in revenue—namely a 1 percent interest rate over 20 years and a three year deferral period before the first payment is due. The idea closely resembles a proposal laid out by Adam Ozimek of Upwork and John Lettieri of the Economic Innovation Group earlier in the spring. By going beyond simply supporting payrolls, the loans should allow viable businesses to improve their balance sheets, refinance debt, and invest for future growth—all necessary ingredients to ensure their own survival but also a robust recovery from the pandemic nationwide.

The proposal starts by targeting seasonal businesses and those located in the very low-income communities that are on the frontlines of both the public health and the economic crises wrought by COVID-19. While there’s good reason to extend the facility to imperiled small businesses beyond those especially troubled cores, the initial proposal is a milestone in congressional efforts to begin to address the societal inequities that the pandemic has laid painfully bare. This post analyzes the demographic and economic composition of the very low-income communities the proposal targets and finds, among other things, that it would reach two-thirds of the country’s majority-Black neighborhoods and half of its majority-Hispanic ones.

Refining the definition of a low-income community

Generally, a Low-Income Community (LIC) is defined by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as a census tract with a poverty rate of at least 20 percent or a median family income 80 percent or less than the area it is benchmarked against (metropolitan area for metropolitan tracts, state for rural tracts). In the latest available data from the 2014-2018 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 28,591 census tracts met at least one of these criteria or 39.1 percent of all census tracts nationwide.

The Rubio-Collins package refines the operative definition of a low-income community even further and requires that both criteria be met to capture genuinely and especially high-need communities. Roughly half of all LIC census tracts, 15,573 in total comprising 21.3 percent of all census tracts nationwide, meet both the poverty and the MFI criteria. Requiring that places meet both criteria ensures that the policy targets high-need areas that demonstrate economic hardship from multiple angles. Accordingly, these “dual” criteria LICs register as especially economically disadvantaged across a wide range of metrics and capture a large fraction of the country’s majority-minority communities.

Economic and demographic profile of “dual criteria” LICs

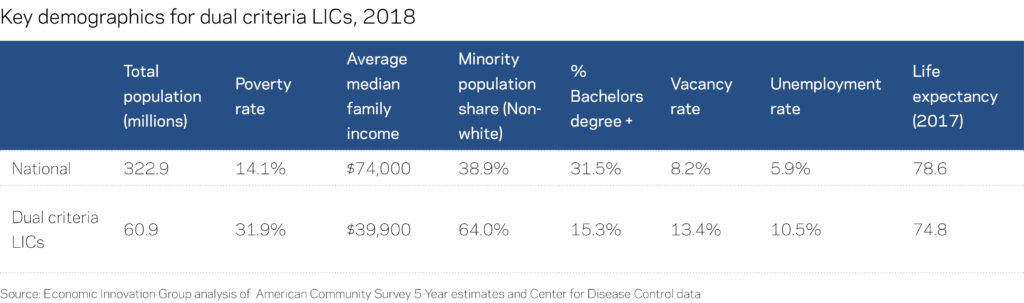

These dual criteria LICs are home to 60.9 million people, representing 18.9 percent of the nation’s population. The average poverty rate in a dual criteria LIC is 31.9 percent, more than double the national poverty rate of 14.1 percent. Only 15.3 percent of individuals over the age of 25 living in a dual criteria LIC have obtained a bachelor’s degree or more education, less than half the national share of 31.5 percent. The median family income in a dual criteria LIC is nearly half the national average, $40k compared to $74k. At just 74.8 years, the average life expectancy in a dual criteria LIC is substantially lower than the national average and approximately the same as in Mexico. The average unemployment rate in a dual criteria LIC was 10.5 percent or nearly double the national rate, before the current crisis.

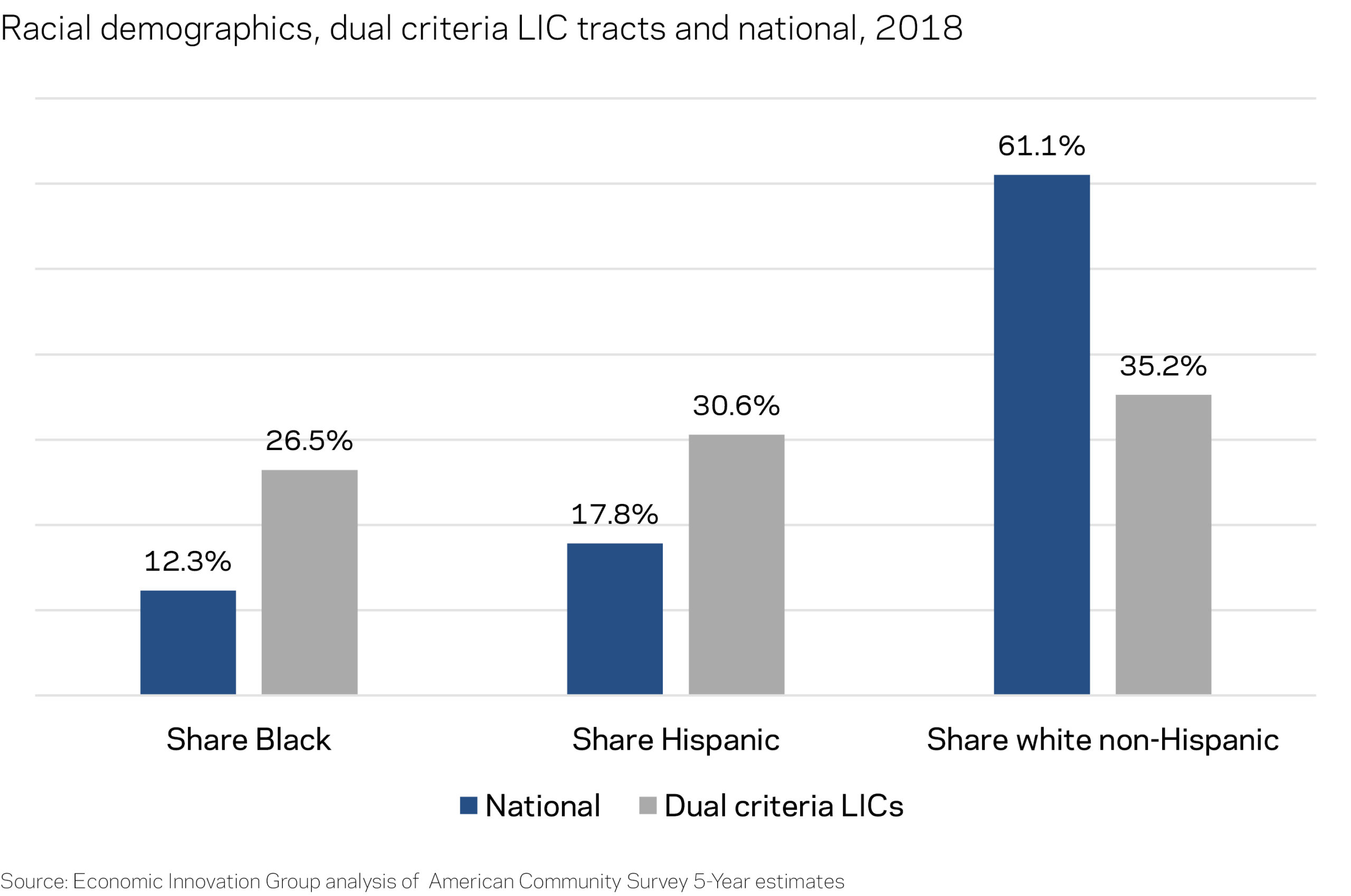

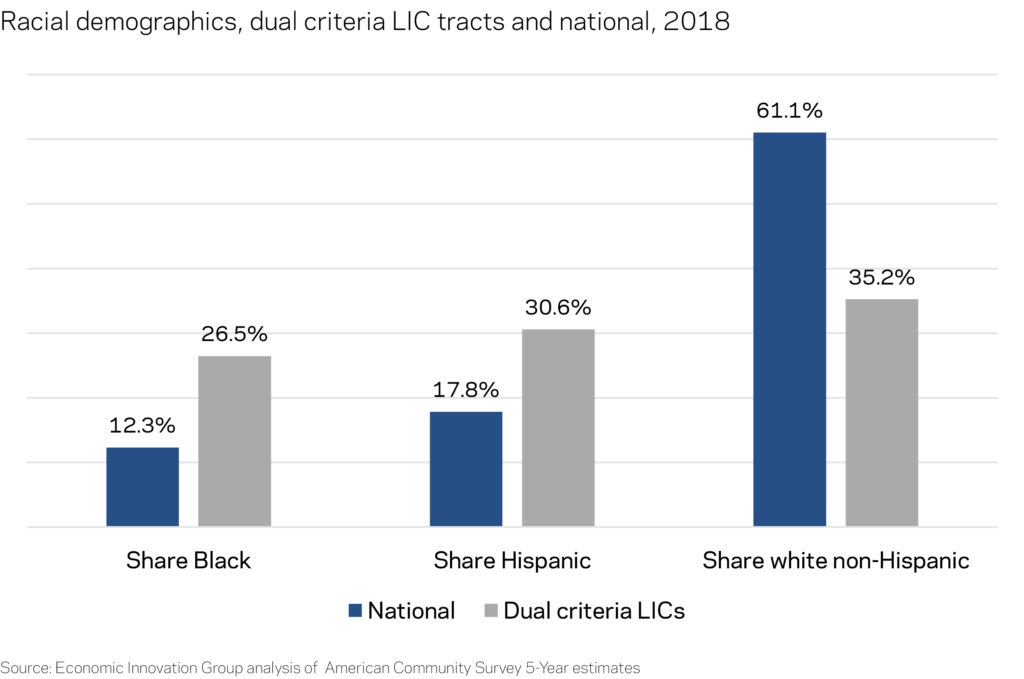

Sixty-four percent of the population of the average dual criteria LIC is non-white. Two-thirds of census tracts that meet both LIC criteria are majority-minority. A quarter of dual criteria LIC tracts are majority Black, representing nearly two-thirds of majority Black neighborhoods nationwide (65.8 percent). Half of majority Hispanic neighborhoods meet both LIC criteria. The country as a whole is 61.1 percent white, while the white share of the population across all dual criteria LIC tracts is just 35.2 percent.

There are approximately 2 million businesses located in dual criteria LICs, according to data from the U.S. Postal Service and ESRI, representing 23 percent of all U.S. businesses. There are additional 400-800K sole proprietorships. Over 30 million employees, or approximately one-fifth of all U.S. workers, work in dual criteria LICs. Not all of these businesses would be eligible for the new loan program, but the figures demonstrate that a large fraction of the country’s small businesses—and likely an even larger share of the country’s minority-owned businesses, given the demographic composition of targeted neighborhoods—would be able to tap into the new facility.

Geography of targeted communities

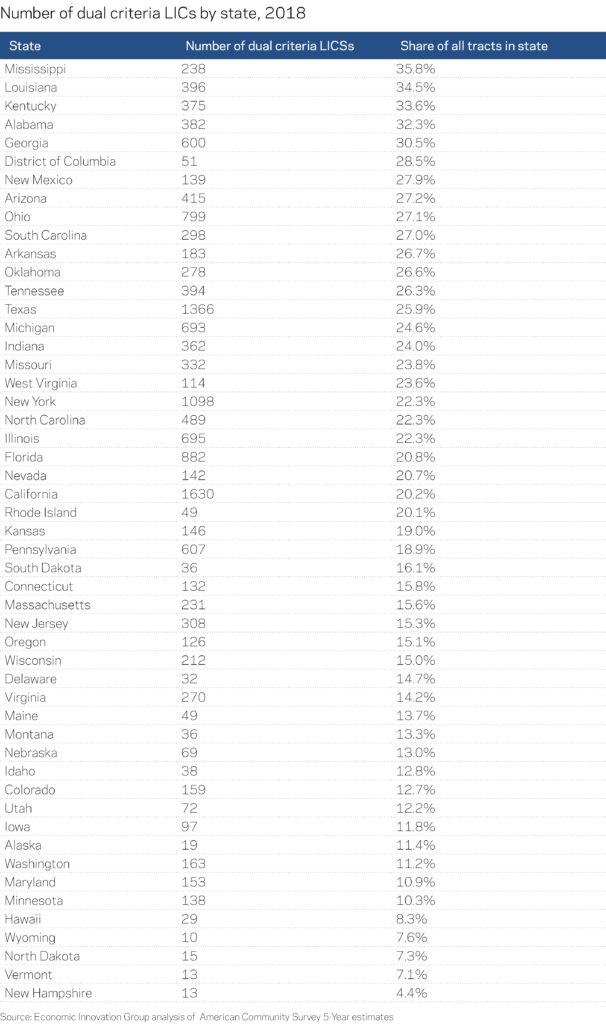

The highest concentration of dual criteria LICs are found in Southern states. More than one-third of all census tracts in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Kentucky are dual criteria LICs. California has the highest total number of dual criteria LICs, and one-fifth of all its census tracts meet the criteria. Only five states have less than 10 percent of their census tracts classified as dual criteria LICs: New Hampshire, Vermont, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Hawaii. In total, 81.7 percent of dual criteria LICs are in metropolitan areas, while 18.3 percent are outside of metropolitan areas. 12.3 percent of these dual criteria LIC tracts are predominantly rural.

(See bottom of this post for a table of targeted census tracts by state)

Conclusion

One lesson of the last recession is that policymakers failed to adequately intervene on behalf of the country’s most vulnerable communities, who in turn experienced a very poor recovery. That lesson is made all the more salient today by the outsized impact the pandemic is having on poor and minority communities. While there’s a strong case for broadening eligibility for the enhanced 7(a) program, the Rubio-Collins proposal is rooted in communities that are experiencing the strongest headwinds in the current crisis. That is appropriate and worth commending.

Even as Congress considers ways to broaden the legislation, geographic targeting can remain an important feature of the policy through the use of set-aside funding, streamlined eligibility requirements, and other mechanisms that ensure the needs of our most vulnerable and disadvantaged communities are intentionally factored into the next phase of small business relief.