by Kenan Fikri

Immigration is a catalyst for economic development. This fact gets lost in the rhetoric around the issue, however. Border security and humanitarian concerns dominate the debate, crowding out economics—and nearly everything else. The issue quickly gets politicized and compartmentalized. And when economic concerns do break through, they get bureaucratized, reduced to fights over specific visa counts in specific visa categories. Rarely is immigration recognized clearly and simply as a critical ingredient of prosperous and thriving local economies—with a reasoned policy discussion flowing from there.

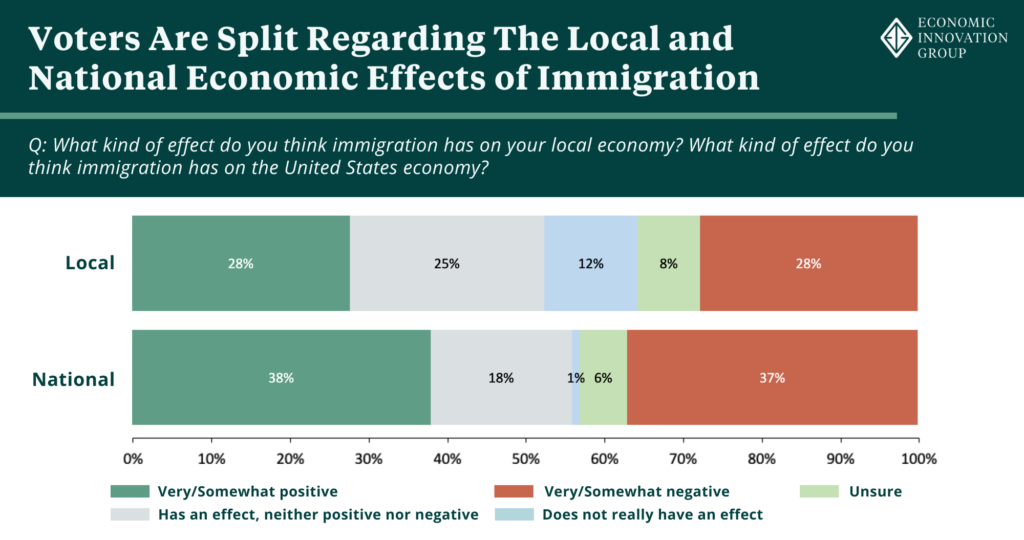

A recent survey conducted by the Economic Innovation Group found that Americans do not have a strong grasp of the role immigration plays in their local economy. Whereas three-quarters of voters have firm beliefs about whether immigration is good or bad for the national economy, only 56 percent feel it has much of an impact locally.

Promisingly, there is a growing body of evidence that localizing immigration can depoliticize it. That opportunity for a more level-headed debate can be pried open more widely with a fuller set of facts about immigration’s role in the economy—starting right at home.

Immigration advances local economic development in numerous ways. Most fundamentally, human capital is the feedstock of the modern knowledge economy, and immigration increases its supply. Given the ambition and determination inherent in the decision to emigrate in search for a better life, those who self-select into becoming an immigrant are often hardworking, risk-taking, and entrepreneurial by nature. They fill gaps in local labor markets, complement American workers, and introduce more dynamism into the system. [1] The greater their skill mix, the greater their economic impact. But immigration works to boost local economies in more indirect but no less significant ways, too. Here we unpack some of the mechanisms through which immigration advances local economic development:

- Population growth. Immigrants directly contribute to local population growth, which itself is an important driver of economic development. Population growth puts wind in the sails of a local economy. It encourages investment, expands the consumer base, and secures a growing labor supply for local companies and those looking to set up shop. Just as population and economic growth reinforce each other, though, the inverse—population loss—can trigger a whole host of negative feedback loops that lock places into economic decline. With the country’s birth rate falling, immigration from abroad has assumed a greater role in determining whether many communities grow or shrink, and how quickly.

- Fiscal health. Immigration in general and skilled immigration in particular provides states and localities with a fiscal dividend that can be used to re/invest in communities. The National Academies of Sciences estimate that the net direct state and local fiscal impact of an immigrant and their immediate descendants over a 75-year time horizon is modestly positive overall and significantly positive for Bachelor’s degree (+$50,000) and advanced degree (+$109,000) holders. [2] The marginal benefit of each immigrant will often be even greater in areas experiencing population loss, where fixed costs of providing services get spread over an otherwise shrinking population. By supporting demand for housing (and therefore house prices), immigration can bolster property tax revenues for municipalities, too. [3] Over the longer term, the positive fiscal impact of immigration only grows with each generation.

- Innovation. Innovations stem from ideas and risk-taking, and immigrants tend to have both aplenty. Immigrants with a college degree are twice as likely to hold a patent than native-born four-year degree holders. [4] In the end, immigrants represent 18 percent of global patent-filers in the United States, are inventors or co-inventors of about 25 percent of all technologies developed in the United States, and account for 33 percent of all U.S. Nobel Prizes. [5] Despite accounting for only 16 percent of inventors, immigrants have generated 30 percent of aggregate American innovation since 1976. [6] Immigrants bring with them different perspectives, unique experiences, and entirely new approaches to problem-solving that enhance local innovation ecosystems.

- Entrepreneurship. Immigrants start businesses at twice the rate of native-born residents. Today, 20 percent of existing firms are owned by an immigrant, a figure that rises to 29 percent in New York and 36 percent in California. [7] What is more, 25 percent of new firms are started by immigrants—meaning one out of every four new American entrepreneurs are foreign-born. Immigrants or their children represent 44 percent of the founders of the Fortune 500 [8] and have started 55 percent of America’s startup companies valued at $1 billion dollars or more. [9] In places like Chemung County, NY, foreign-born entrepreneurs behind companies such as Chobani are leading local economic revitalization. Their proclivity towards entrepreneurship makes immigrants net job creators for the U.S. economy. [10]

- Productivity. Immigrants boost the productivity of native-born workers, be it within individual companies, in local labor markets, or nationwide. It happens because immigrants are complementary to native-born workers. [11] At the lower end of the labor market, a steady stream of immigrant labor can free native-born residents to do higher value-added activities. At higher ends of the labor market, human capital functions much like physical capital: just as a computer makes a knowledge economy worker more productive, so does having skilled and creative colleagues from different backgrounds. [12] According to one estimate, skilled immigrants generated 30 percent to 50 percent of total U.S. productivity growth between 1990 and 2010, and another study finds that the productivity advances generated by STEM immigrants boost native-born wages at the local level. [13] What is more, the dependable supply of labor that immigrants represent induces firms to invest, growing the overall stock of capital in the economy. [14]

- Global connectivity. Immigrants’ global connections foster trade and knowledge flows. Even at the scale of regional economies, when immigrants settle in an area, trade with their home countries flourishes. Thanks to immigrants’ knowledge of their home country’s opportunities, laws, and customs, immigrant connections reduce information costs. [15] In particular, immigrants can help when trading with developing countries with a variety of bureaucratic and legal hurdles. [16] Immigrants are also more likely to collaborate with foreign inventors and be conduits for useful knowledge from abroad to make its way into American innovation ecosystems. [17]

- Placemaking. Immigrants contribute directly to placemaking through the economic vitality and diversity of their businesses. From shopping to cuisine, immigrants help make communities destinations. In the hospitality sector, 38 percent of business owners were born outside the United States, as were 24 percent of retail business owners. [18] Immigrants are bulwarks of complete streets, and in cities and towns across the country, immigrant-owned businesses are anchor tenants of Main Street America. In metro areas such as Memphis and Birmingham, immigrants own more than five times the share of Main Street business as their population would suggest. [19] Oftentimes, cultural events and ethnic festivals throughout the year help strengthen the local social fabric, too. In short, immigrants bring energy and vitality that can help renew the spirit of a place—essential, dynamic ingredients for neighborhood-scale economic development.

What other economic development solutions yield such a broad and robust array of benefits to local communities? The higher an immigrant reaches on the education and earnings ladder, the greater their impact on nearly every one of these fronts, too. With 85 million Americans living in counties with shrinking or stagnant populations and 160 million Americans residing in counties that lost prime working age adults from 2011 to 2021, it is time to reframe the immigration conversation around local and regional economic development. [20]

Nationwide, 13.6 percent of the population was born abroad, but the geographic distribution of the immigrant population is extremely lopsided. In several of the country’s most dynamic and innovative cities around Silicon Valley, for example, half of the local population is foreign-born. In legacy cities of the Northeast, such as Fall River, MA, or Providence, RI, immigrants represent one-quarter to one-third of the population, shoring up the economic base of their new hometowns. But the local economic benefits of immigration remain concentrated. The 20 most populous U.S. counties contain 36 percent of the country’s immigrants with at least a Bachelor’s degree, compared to only 19 percent of the country’s total population. [21] The majority of Americans are underexposed to the significant and real local economic upsides of immigration.

Immigration is, first and foremost, a source of economic capacity and dynamism. It is hard to see how the deadlock that has prevented meaningful immigration reform in the United States for decades will break without recognizing it as such. State and local leaders in particular need to advance a bottom-up framework for understanding why immigration matters for the United States and become more fluent in the value their communities derive from immigration. There are real human costs to our national inaction on immigration. In communities across the country, there are real and growing economic opportunity costs, too.

.

Sources

- Zavodny, 2023.

- NAS, 2017.

- Mayda, Senses, and Steingrass, 2022.

- Kerr and Kerr, 2020.

- Kerr, 2018.

- Bernstein, Diamond, McQuade, and Pousada, 2021.

- Annual Business Survey, 2020.

- American Immigration Council, 2022; Center for American Entrepreneurship, 2017.

- National Foundation for American Policy, 2022.

- Azoulay, et al., 2020.

- Peri et al., 2015.

- Moretti, 2012.

- Peri, Shih, and Sbarber, 2015.

- Clemens, 2023.

- OECD, 2022.

- Parsons and Vézina, 2014.

- Bernstein, Diamond, McQuade, and Pousada, 2021.

- Annual Business Survey Characteristics of Business Owners, 2021.

- AC/COA, The Impact of Immigrants on Main Street Business and Population in U.S. Metro Areas, 2015.

- EIG analysis of 2021 ACS data.

- EIG analysis of 2021 ACS data.