By Kenan Fikri, August Benzow, Nora Esposito, and Kennedy O’Dell

Key findings:

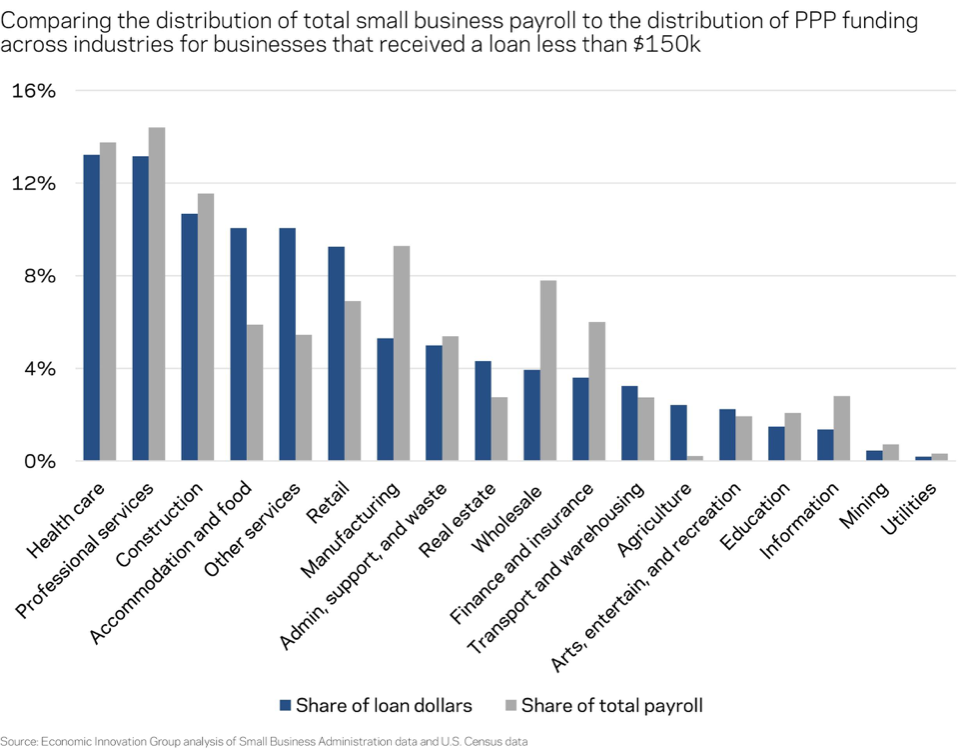

- PPP loans for less than $150,000—representing 86 percent of all loans under the program—targeted many of the hardest-hit industries. Accommodation and food services, retail, and other services such as laundromats and hair salons received much greater shares of small-dollar funding than their shares of total small business payroll would have predicted.

- The arts, entertainment, and recreation industry is the exception, as small businesses in the hard-hit sector did not appear to tap small-dollar PPP loans disproportionately.

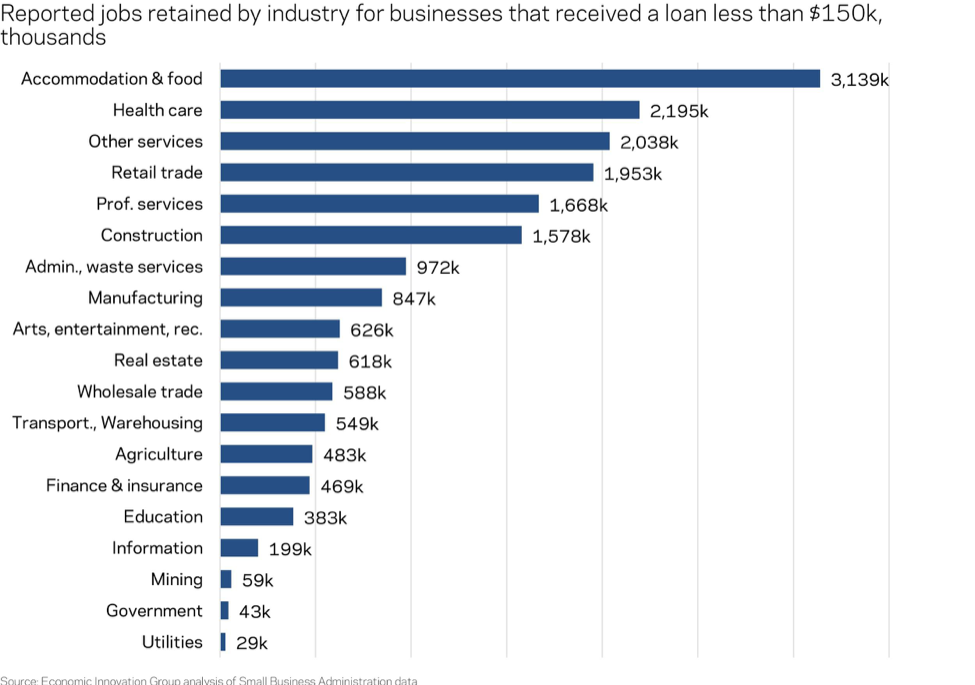

- Recipients of small-dollar PPP loans preliminarily reported retaining a total of 18.4 million jobs with the funding, including 7.8 million in the four sectors on the front-lines of the economic fallout from COVID-19.

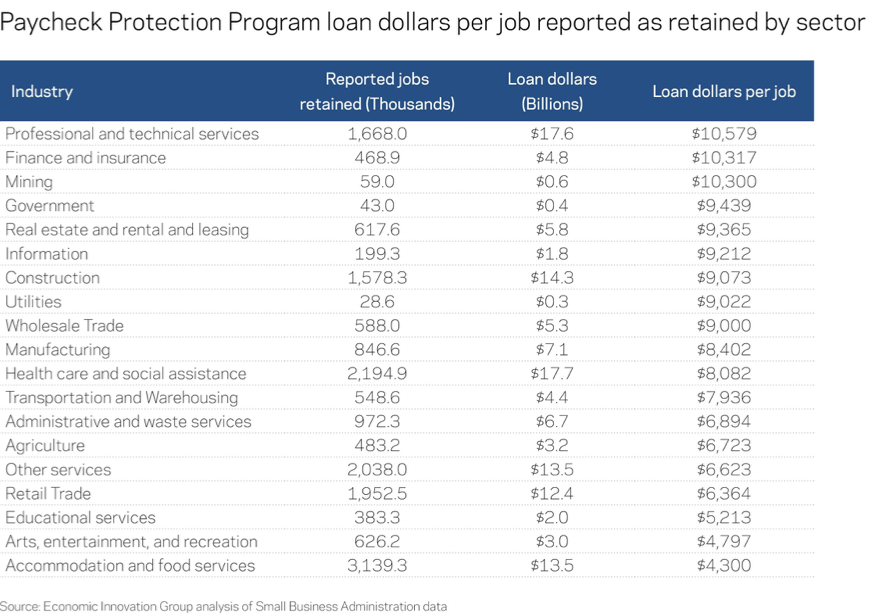

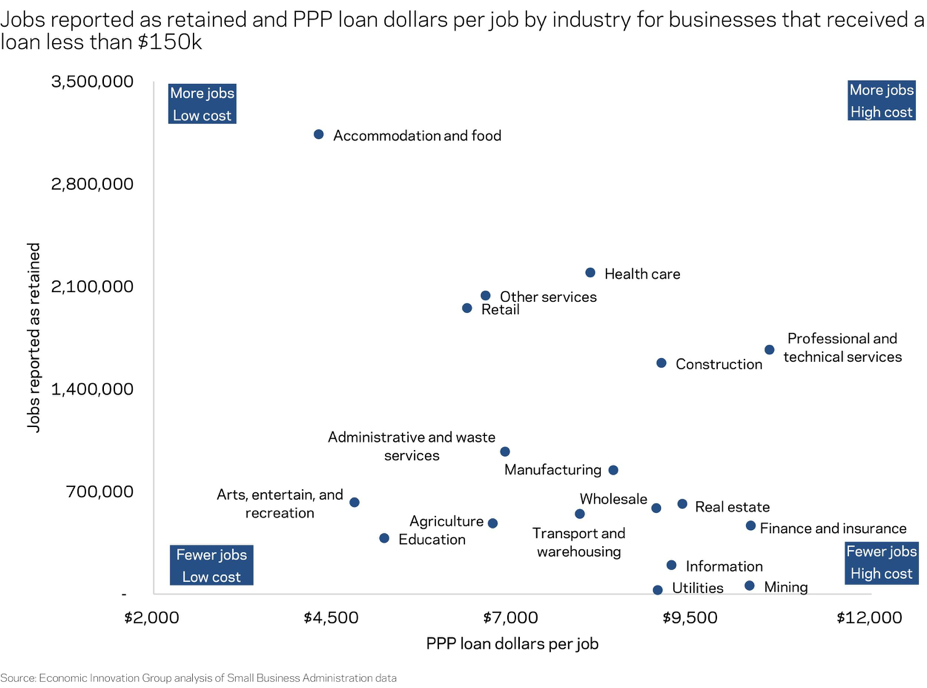

- The cost per reported job retained of the relief varied widely across industries, from $4,300 in accommodation and food services to $10,600 in professional services.

- Ultimately, the same amount of PPP relief helped retain a reported 2.5 jobs in the accommodation and food services industry for every one it reportedly helped retain in professional services.

- This analysis suggests that adapting relief to target the businesses suffering the most harm from the pandemic could be disproportionately effective in shoring up the low wage end of the U.S. labor market and be significantly cheaper than a less-scoped alternative

The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was passed and implemented with near-record speed for a federal endeavor of its magnitude. By most fair assessments, it rose to the challenge that COVID-19 presented in providing urgent stop-gap relief to the nation’s imperiled small business sector. PPP reached deep into the economy and extended more than $500 billion in loans to nearly 5 million American small businesses. As of early July, the program appeared to be supporting, at least temporarily, the equivalent of two-thirds to three-quarters—and by some estimates even more—of the country’s entire small business workforce.

Yet to achieve speed and scale, the program had to compromise on precision targeting. PPP loans were made available to all-comers on the same terms, regardless of actual economic harm. Although loan sizes and eligible covered salaries were capped, the program appears to have been much more cost-efficient in supporting jobs in some industries than others. (For a discussion of other shortcomings of the program, see here). The cost in federal support per job that borrowers report retaining is by no means the only measure against which to gauge success, but it does provide an accessible shorthand for evaluating the efficacy of the program in meeting its stated intent of protecting paychecks.

This analysis breaks down the distribution of PPP small-dollar loans and reported jobs retained by industry. It finds that the program is supporting jobs across every industry, but that much more bang for the buck is being delivered in supporting the low wage jobs in sectors most deeply affected by the pandemic than high wage jobs more on the periphery. As Washington grapples with the need for more relief but shrinking political willpower for delivering it, these insights should inform the next round of crisis policymaking.

Methodology

This analysis utilizes the detailed state by state small loan data made available by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) as well as the national summary report through June 30th. Our analysis is specific to the anonymized data for loans under $150,000, which includes information on reported job retention as well as exact loan amounts, in contrast with the data for larger loans. This combination allows us to estimate how many reported jobs were retained per dollar of PPP funding across industries. We further constrain the sample by eliminating any records with no industry detail or an unclassified or government categorization. In total, this analysis covers $134.2 billion of the total $521.5 billion in loans disbursed under PPP and encompasses 86 percent of all individual loans originated.

The reported jobs retained figures provided by SBA are only preliminary at this point and warrant several important caveats. The program requires these figures for loan forgiveness, but borrowers are not required to provide them at the time of origination. This analysis assumes that any initial reporting bias is random and evenly distributed across industries. In addition, it is impossible to verify that PPP was indeed the decisive factor in determining whether a job was retained. It is quite likely that many employers were only able to retain some workers due to the lifeline offered by PPP, but few program rules prevent others from opportunistically using the money to support jobs they would have retained anyway.

Finally, data on recent industry job losses due to the pandemic are derived from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Report, and total small business employment and payroll figures are derived from the Census Bureau’s Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) for all firms with fewer than 500 workers for the year 2017. Some non-employer businesses such as sole proprietors or the self-employed are not captured in the SUSB data but were eligible for PPP and are included in our PPP-related calculations.

Findings

1. PPP funding favored many deeply affected industries

The distribution of small-dollar PPP funding across industries shows that the program succeeded in reaching small businesses in many of the industries most deeply affected by the pandemic. Accommodation and food services, retail, and other services (including personal care, laundry services, and repair) all received a far greater share of small-dollar PPP funding than their share of total small business payroll would have predicted. The arts, entertainment, and recreation sector, however, only received a proportional share of small-dollar PPP funding, leaving it anomalously underserved by PPP among industries at the epicenter of the crisis. The three largest industry beneficiaries of small-dollar PPP funding, the healthcare, professional services, and construction sectors, received close to proportional amounts, given their large payrolls.

2. PPP reportedly preserved 7.8 million jobs in hard-hit sectors

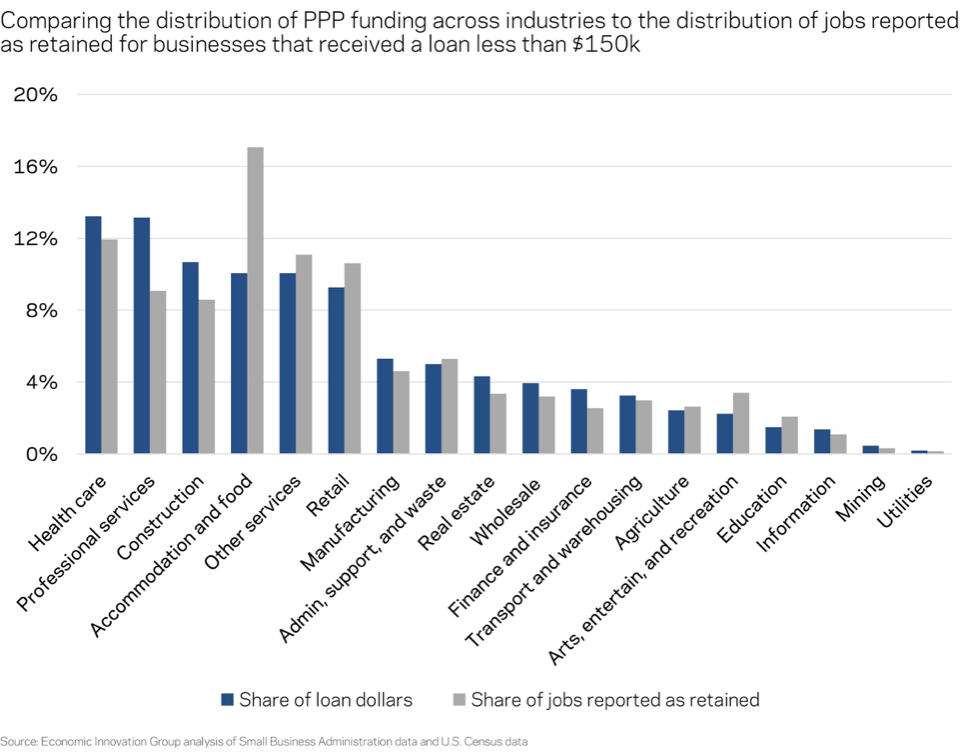

Comparing the distribution of small-dollar PPP funds to the distribution of reported jobs retained from the relief paints a much different picture. In total across the industries analyzed here, small-dollar PPP loans preserved a reported 18.4 million jobs.

These small-dollar loans preserved more reported jobs in the accommodation and food services industry than any other by a significant margin. The industry, which accounted for 14 percent of all jobs at small employer businesses and 6 percent of all payroll before the crisis received 10 percent of all small-dollar funding and with it accounted for 17 percent of all jobs reportedly retained by the pot, or 3.1 million in total. The other three hard-hit sectors—retail, arts and entertainment, and other services—are also responsible for a disproportionate share of the jobs borrowers reported retaining. Combined, the four industries most deeply affected by the crisis accounted for 42 percent of the jobs reportedly retained from small dollar PPP loans (7.8 million in total), compared to their 34 percent share of total small business employment before the crisis. Those 7.8 million jobs equate to almost two out of every five pre-pandemic jobs in those industries. Meanwhile, the professional services sector is the one that comes up the shortest. With 13 percent of small-dollar PPP funding, it accounts for only 9 percent of jobs reportedly retained with the money.

These disparities point to the fact that it is much cheaper to support a low wage job than it is a high wage one.

3. One dollar of small-scale PPP lending reportedly preserved 2.5 jobs in accommodation and food services for every one job preserved in professional services

Preliminarily reported jobs retained figures suggest that small-dollar PPP loans preserved significantly more jobs in lower-wage industries at significantly lower cost than it did in higher wage ones. While nearly $10,600 in small-scale PPP was allocated to each reportedly retained job in the professional services sector, only $4,300 in accommodation and food services and $4,800 in arts, entertainment, and recreation reportedly achieved the same. Looked at from another angle, for the same $17.7 billion in small-scale loans extended to the professional services sector, an additional 4.1 million jobs in accommodation and food services could hypothetically have been preserved based on the ratios calculated here, compared to the 1.7 million jobs that loan recipients in the professional services industry reported retaining instead.

—

Preserving jobs irrespective of their industry or wage level is a worthy policy goal and was the right one to set at the start of the pandemic. It is economically astute, given that one sector’s wages provide another sector’s demand, and it also sends an important signal of solidarity at a time when the economy and society are under siege. In sectors such as healthcare, PPP may have prevented mass layoffs of essential workers, enabling hospitals, doctors offices, dentists, and care workers to maintain staff and service levels even as revenue streams dried up. In professional services and other higher wage sectors that face more of a temporary downturn than a permanent change in consumer behavior, PPP dollars may have prevented major layoffs and buttressed the overall economy in other ways as well. Unquestionably, the four hardest-hit industries would have lost even more than the 6.9 million jobs that disappeared between February and June had PPP not thrown a lifeline to millions of workers.

As a return to normalcy edges ever farther off the horizon, however, it is becoming increasingly clear that PPP’s wide-open approach was a one-time luxury that the country is unlikely to be able or willing to repeat again. The measure of reported jobs retained per dollar evaluates PPP by only one limited but important angle. These data suggest that adapting relief to target the businesses suffering the most harm from the pandemic could be disproportionately effective in shoring up the low wage end of the U.S. labor market and be significantly cheaper than a less-scoped alternative.