by Daniel Newman

With reservoirs in the southwestern United States at record-low levels and the effects of prolonged drought conditions being felt from agriculture to development, one of the most far-reaching questions over the coming decades is whether the ongoing growth in the economically successful region is sustainable—and what tradeoffs will be necessary to make it so. A provision of the Inflation Reduction Act will direct $4 billion to support drought resilience, an important investment that could help some of the driest states adapt to climate change and sustain their fiery pace of population growth.

A drop in the bucket or precious relief?

The funds came at the request of Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, a state in which nearly every county has spent at least half of the past 10 years under severe drought conditions while adding nearly 720,000 residents over roughly the same time. The federal investment should help the increasingly hot and dry Southwest bolster itself against some of the economic losses that could arise amid an increasingly constrained water supply, which will need to support potentially millions of new residents in the coming years.

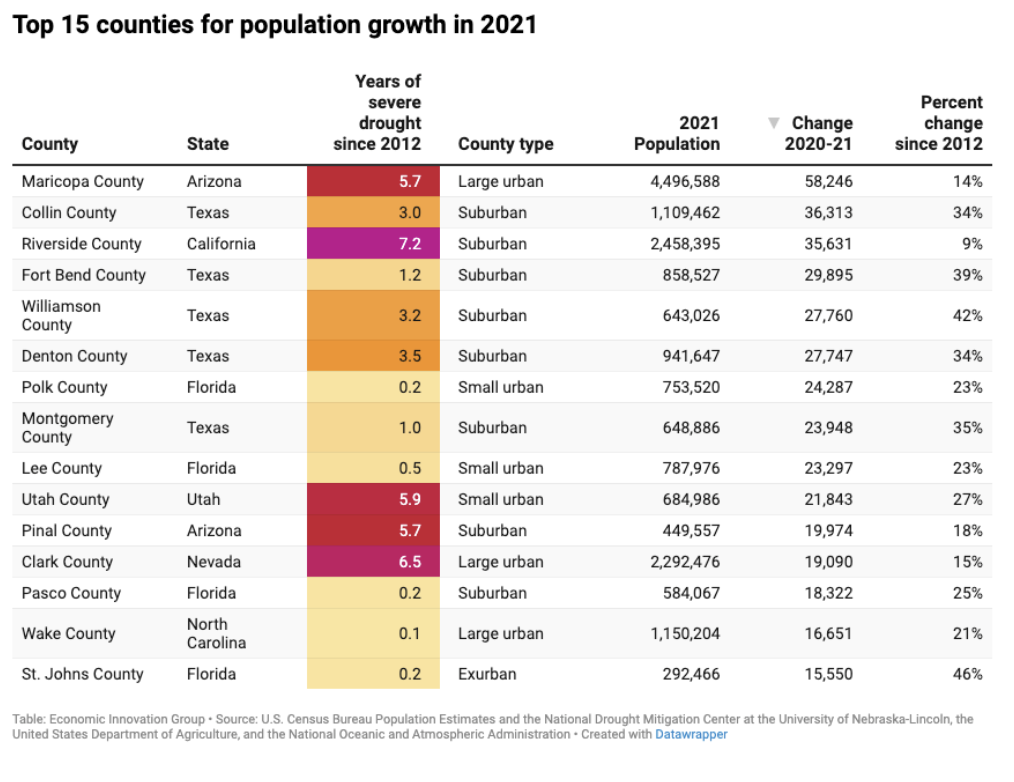

Even as the U.S. experienced the slowest population growth on record last year, some of the country’s most water-starved states continued to attract job-seekers and retirees alike with generally good economic growth and a relatively lower cost of living in places like Arizona, Utah, and Texas. Ten of the 15 counties with the largest increase in residents last year were in the parched Southwest, led by Maricopa County, Arizona—home of the fast-growing Phoenix metro area.

Since 2012, an additional 2.8 million people have come to reside in counties that spent a majority of the 10-year period under "severe" to “exceptional” drought conditions—a situation under which crop or pasture losses become likely and water shortages are common, often requiring the imposition of usage restrictions. But the fragile balance between development and sustainability that has enabled growth in the Southwest to date could be reaching an inflection point. Starting for the first time next year, 40 million people in Western states reliant on the Colorado River will have to contend with mandatory reductions in the amount of water they can obtain from it.

In Summit County, Utah, the town of Oakley made headlines last year as one of the first places to temporarily limit development as a consequence of drought conditions. The county has spent just under five years in severe drought conditions since the summer of 2012, and about half that time has been under more extreme drought conditions that have traditionally meant an increase in fire danger and significantly reduced water levels in streams and rivers. Small and rural communities like these are often the first to face consequences as water restrictions are implemented, unable to spend on costly adaptations.

Quenching the thirst

Unless current migration and growth patterns change significantly, these same places are poised to continue adding millions of residents in the coming decades. Those counties that have spent more than half of the past ten years under severe drought could be home to 8.6 million more residents by 2035, according to a “middle of the road” growth projection from the NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center, which estimated future population changes based on a scenario involving medium challenges to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Yet, population growth on its own is not the only (or biggest) contributor to the region’s water woes. That responsibility falls primarily on the agricultural sector, which uses nearly 80 percent of the region’s water supply. The arid Southwest is highly dependent on irrigation for its crops, and the extremely valuable sector—producing about one-fifth of the country’s total agricultural cash receipts—faces the challenge of adapting to the changing climate norms. The region must balance this sector’s needs with the growing demand of a ballooning urban population. Water rights are highly regulated in the region, and those parties with longstanding access may be at an economic advantage relative to the region’s newcomers.

If anything, investments in drought resilient infrastructure seem poised to only grow in importance in the coming years. The record-high temperatures blanketing the country in the summer of 2022 are a timely reminder of the extreme heat and drought conditions that have become increasingly common across the country. As climate change accelerates, it presents an ever larger threat to life and continued economic development in what is currently one of the country’s most dynamic regions and strongest economic engines. Evolving climate realities will have national implications that present uncomfortable trade-offs between land uses and significant lifestyle changes, or changes to migration patterns as nature asserts itself against Americans’ desire to live in increasingly hotter and drier locales.