Originally published on Agglomerations, the Substack newsletter from the Economic Innovation Group.

By Sam Peak and Connor O’Brien

In February, President Trump first proposed a “Gold Card Visa” for high-net-worth individuals to immigrate to the United States, with a suggested price tag of $5 million.

If designed correctly, the new Gold Card could advance several administration and national priorities like reducing the federal budget deficit, curtailing the flow of fentanyl at the border, and financing disaster relief. As a simpler alternative to the cumbersome EB-5 investor green card, the Gold Card Visa could also yield much larger and more certain benefits for American communities depending on how it is structured.

The existing system for international investors has major shortcomings

The EB-5 Investor Immigrant Program established by the Immigration Act of 1990 allows foreign nationals to obtain conditional permanent residency if they invest at least $1,050,000 in a new commercial enterprise that creates 10 or more jobs. This threshold is lowered to $800,000 if the investment is directed to a Targeted Employment Area (TEA), a rural or high unemployment area, or an infrastructure project. Nearly all successful EB-5 applicants qualify under the lower threshold.

Investor visas are especially challenging to design in practice. Most require some empirical demonstration of impact, involving both lengthy business plan reviews from bureaucrats and expensive economic consultant analyses. Such requirements make investor visas unviable for high-risk, high-growth startup founders operating on tight timelines. The EB-5, which is difficult to use and whose economic impact remains highly uncertain, is no exception.

The EB-5 visa has by far the longest processing times in the U.S. immigration system. The median applicant filing a petition for the EB-5 waits 71 months for a decision. Afterward, the applicant receives a provisional green card and must wait two years to see if jobs were created from their investment. For the median applicant, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) takes anywhere from 17 to 49 months to verify that the investment did create jobs. If the applicant is successful, they are finally granted a full green card.

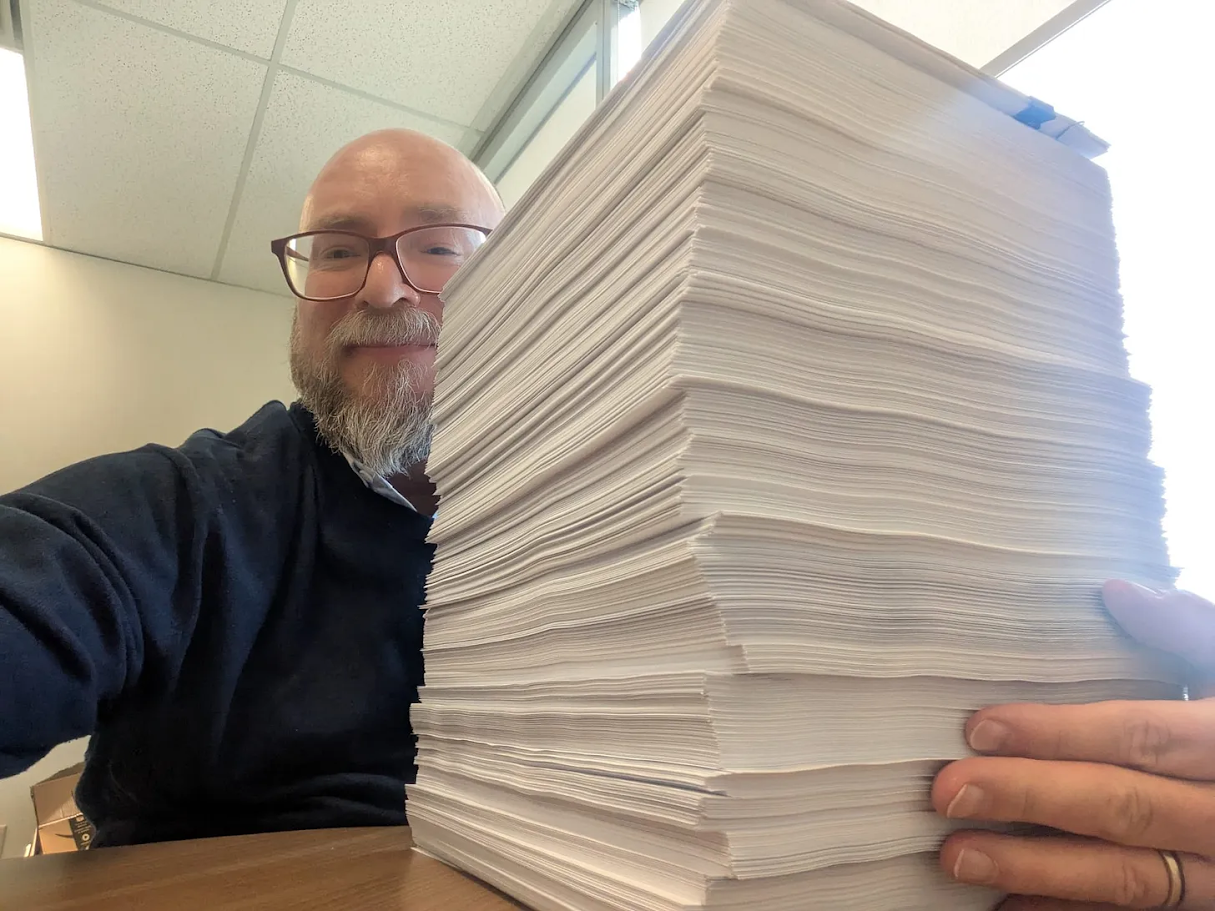

Below is a picture of what the EB-5 paperwork looks like for proving job creation. This is a small portion of the total paperwork that EB-5 applicants must submit to USCIS.

Credit: Pace Immigration on X/Twitter: https://x.com/paceimmigration/status/1902398183084343415

While the EB-5 visa requires that investments each create 10 jobs, the Regional Center pathway that receives the vast majority of EB-5 investments allows 90 percent of those jobs to be “indirectly” created, either through spending on outside vendors or “induced” growth through employees’ spending power.

To demonstrate this job creation, applicants typically spend thousands of dollars on professional economists to run RIMS II or IMPLAN models, which assume certain ratios of job creation to investment by geography.

Notably, these estimates only model local job creation. Such models are not capable of determining whether an investment increases aggregate, nationwide employment. There is little solid, empirical evidence that the EB-5 program as constructed today generates substantial job growth that wouldn’t happen without the program.

Job creation is certainly one of the main benefits of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), but when the process takes nearly six years and still only generates speculative estimates of job creation, it’s time to consider alternatives.

As the EB-5 Regional Centers come up for reauthorization in 2027, lawmakers should pursue bold reforms that make the program more straightforward to use, flexible, and directed towards outcomes that are easy to measure.

For now, the flaws in the EB-5 program demonstrate mistakes to avoid when designing a new Gold Card Visa. Below, we make two suggestions.

Approach 1: Charge a $5 million fee (or use an auction) to reduce the deficit.

The best option for a Gold Card Visa is President Trump’s original proposal: use revenues to reduce the federal deficit.

Policymakers can do this in one of two ways. First, the Gold Card program could charge $5 million per applicant, in line with the President’s original proposal. In this case, the limiting factor on the amount of revenue a Gold Card could generate is the number of applicants willing to pay this fixed fee.

According to estimates from Knight Frank, a real estate consultancy, there are about 1.4 million people living outside the United States with a net worth of at least $10 million. It is unclear, however, how much take-up there would be among this population if the U.S. rolled out a Gold Card Visa.

Alternatively, the Gold Card program could maximize revenue by using a Dutch auction to allocate a fixed number of visas. USCIS would offer each visa at a high starting price ($5 million), gradually lowering the price until the first bidder accepts. This process should be subject to a minimum bid, perhaps $1 million, to ensure each visa auctioned off generates significant revenue for American taxpayers.

Depending on the size of the Gold Card program and auction results, the program could generate tens of billions in annual revenue. On the conservative side, a 10,000 visa per year program (the current size of the EB-5) which sells Gold Card Visas for $1 million each (the approximate investment requirement for the EB-5 today) would raise $100 billion over a decade. The President’s proposed $5 million price tag offers a potential upper bound; if 10,000 visas were issued each year with a cost of $5 million each, the program would raise $500 billion over a decade. That would be enough revenue to fully offset the cost of extending the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s Child Tax Credit expansion for a full decade.

At this stage, revenue estimates from a Gold Card program are highly speculative. While there are global surveys of desire to migrate to the United States, there are no surveys specific to high-net-worth individuals who might be interested in a Gold Card. Auctioning off a fixed number of visas rather than setting an up-front price would still allow for a price of $5 million or more while being responsive if interest at that price proves limited.

It’s important to note that the initial sale price is not where the fiscal benefits end. Applicants who can afford the entry price will almost certainly be large net fiscal contributors in subsequent years, starting and expanding businesses that pay taxes. Compared with the existing EB-5 program, allocating Gold Card Visas in this way would yield far larger public benefits and federal revenues. Pre-pandemic estimates suggest about $6 billion of investment takes place through the EB-5 program each year; only a small fraction of this investment likely returns to the Treasury in the form of tax receipts.

Approach 2: Make the Gold Card Visa a revenue source for border security and disaster relief.

Alongside or in lieu of deficit reduction, revenue from a Gold Card Visa could be earmarked for two homeland security priorities: border security and disaster relief.

First, Gold Card Visa fees could be used to supplement U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Donations Acceptance Program, which enables private entities to help fund new inspection lanes, repair projects, and other infrastructure investments that enhance the vetting of cross-border traffic.

To maximize the effectiveness of this revenue, lawmakers should take steps to streamline CBP infrastructure projects, which are frequently delayed. One way to reduce this red tape is to eliminate the involvement of the General Services Administration (GSA), which adds many months to government projects. Lawmakers have previously introduced the REVAMP Act to get GSA out of the way for projects costing less than $300,000. But Congress should go further and exempt all CBP projects from GSA’s review if it decides to use the Gold Card Visa revenue for projects at ports of entry.

Gold Card Visa funding can also be used to rectify gaps in CBP staffing. Currently, the agency has too few officers to operate newly installed image detection equipment at ports of entry. In 2024, CBP estimated a shortage of 5,800 officers and anticipated an 800 percent spike in officer retirements by 2028. Based on DHS’ FY 2025 budget, hiring 1,000 additional CBP officers would cost just $239 million. With just one-fifth of a possible $50 billion in annual Gold Card revenues, CBP could more than double the number of officers staffing American ports.

Second, some portion of Gold Card Visa revenue could be set aside for disaster relief. The EB-5 program has historically supported rebuilding in the aftermath of disasters like Hurricane Maria and Superstorm Sandy, but the glacial pace of its application process means it cannot provide swift relief or quick investment. Merely half of a possible $50 billion in annual Gold Card revenue would cover Congress’ typical annual appropriations for FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund.

As FEMA undergoes an overhaul to grant states more autonomy over disaster response, earmarking Gold Card fees or auction revenues to state emergency management agencies could more effectively meet the local needs of residents. The uses of such funds can be guided by recommendations outlined in the forthcoming National Risk Register, which will identify the greatest risks to U.S. infrastructure and help form priorities for public and private investments.

Conclusion

President Trump’s Gold Card Visa proposal recognizes two major failures of America’s investor visa. First, applying for the EB-5 investor green card is an unacceptably long process that can take up to a decade from start to finish, making it a poor fit for the highest-potential founders with capital ready to deploy immediately. Second, the requirements of EB-5 investors, while well-intentioned, do not yield clear, certain, and prompt benefits to the American people. These flaws need fixing. Alongside an overhaul to the EB-5, the new Gold Card Visa should avoid those flaws in the first place.