By Daniel Newman and Kenan Fikri

Even before the onset of COVID-19, high-poverty neighborhoods were burdened with elevated levels of vacant, underutilized, and abandoned commercial buildings that impeded local economic revitalization.

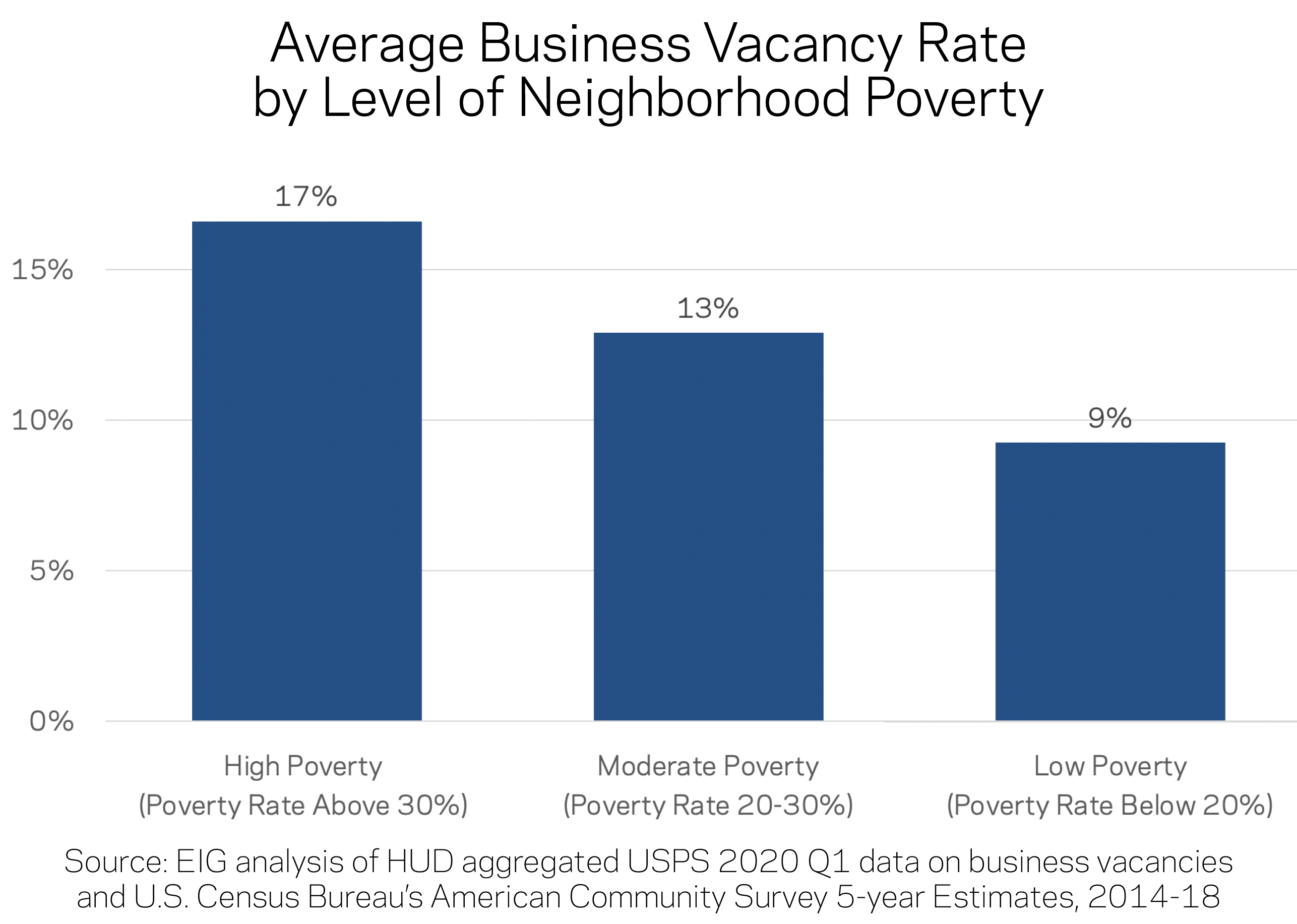

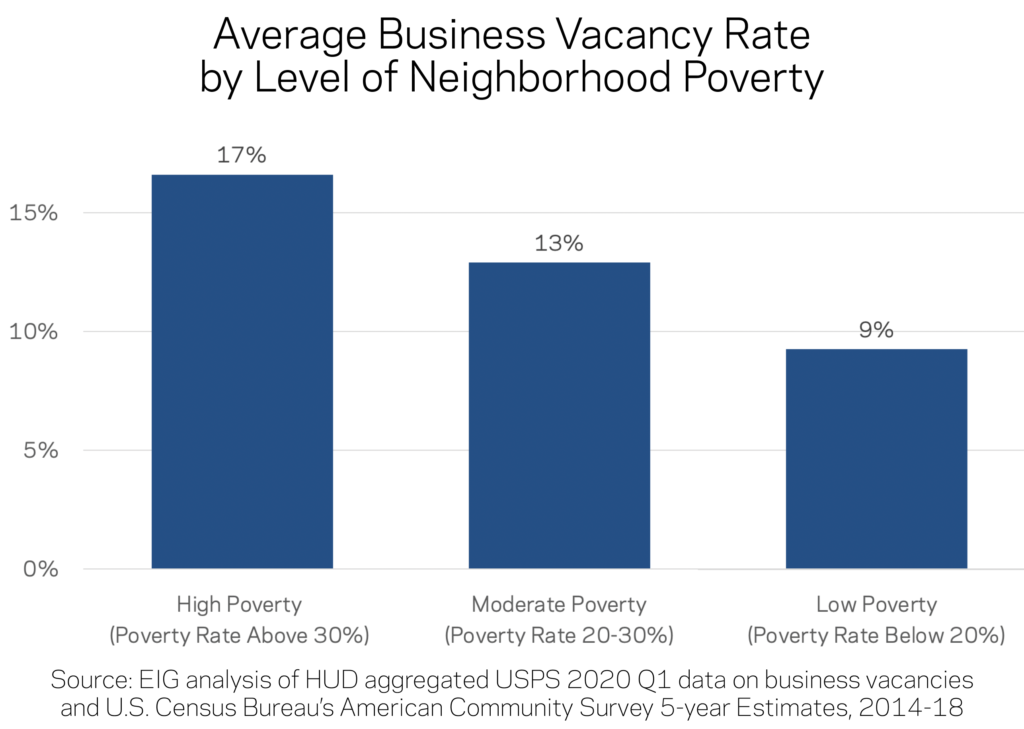

EIG’s latest research initiative, the Neighborhood Poverty Project, tracks the evolution of neighborhood poverty in metropolitan areas since 1980. In neighborhoods that had a poverty rate over 30 percent in 2018, nearly twice as many business locations stood vacant as in low-poverty communities, based on an EIG analysis of data collected by the United States Postal Service before the coronavirus pandemic fully hit. During the first three months of 2020, at least 17 percent of business premises sat empty in high-poverty communities compared with just 9 percent in low-poverty places.1 The current economic crisis is certain to close many businesses nationwide and could potentially push the vacancy rate in these already struggling places significantly higher.

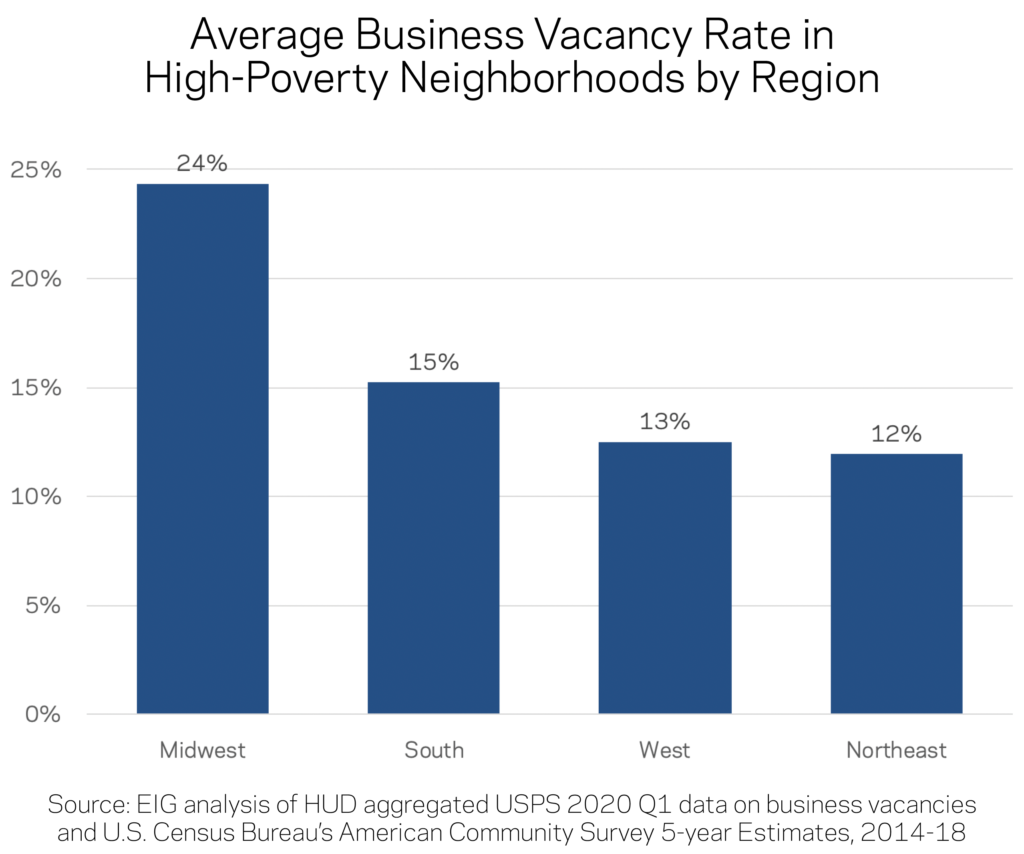

High-poverty neighborhoods in the Midwest look particularly at risk. Compared with other parts of the United States, business vacancy rates in the region are already around twice as high in the most poverty-stricken neighborhoods.

Future trends in business vacancies will depend significantly on whether the federal response to COVID-19 succeeds in preventing a cascade of small business closures and a collapse of new firm formation. There is reason to believe that businesses serving high-poverty neighborhoods are in particular jeopardy right now, given the already disadvantaged circumstances of their communities and customers. If they close en masse, the main street economic backbones of some of the country’s most struggling communities could be devastated as new vacancies pile on top of old ones and hasten neighborhood decline as custom falls away and blight takes hold. The emerging economic survival and recovery playbooks in Washington, D.C. and statehouses should include targeted place-based economic policies that take such interconnectedness between businesses and neighborhoods into account. Coming out of the crisis, Opportunity Zones investments, incentives for blight removal, and brownfield remediation, as well as grants or debt-based instruments to revitalize main streets, will all have roles to play.

1 The United States Postal Service (USPS) provides aggregate vacancy and no-stat counts of business addresses on a quarterly basis. An address is considered vacant after not collecting mail for 90 days. According to USPS guidance, no-stats are addresses that have been abandoned or are under construction and are not yet occupied. Without the ability to determine the actual condition of no-stat addresses, EIG excluded those data points from the total number of business locations and vacancy calculations. Nevertheless, USPS guidance suggests that no-stat addresses in high-poverty neighborhoods have a very high likelihood of being abandoned.