How dynamic is the U.S. economy? Far less dynamic than it used to be, according to EIG’s latest report, Dynamism in Retreat. Fewer businesses open and close each year, fewer workers change jobs, and fewer people are moving across the country than ever on record.

The collapse in dynamism during the Great Recession, particularly the steep fall-off in new business creation, has produced a growing economic crisis that is calcifying our economy. Once innovative, restless, and entrepreneurial, the U.S. economy is now characterized by stasis and incumbency. Restoring dynamism will be necessary to increase productivity, accelerate growth, and restore the promise of a prosperous and upwardly mobile society.

Here are six key points for understanding the problem and its consequences.

1. A drastic fall in dynamism has contributed to the weakness of the recovery.

Declining dynamism is a big reason for the tepid and uneven recovery from the Great Recession. Fewer new firms have started in the years since 2007 than at any point in recent history. Old incumbent companies now employ a record share of the workforce. All this stasis means the economy isn’t growing more productive. The recovery’s headline 80-plus straight months of growth masks the reality that post-recession GDP growth has been 3 percentage points slower each year on average than it needed to be in order to return the country to its 1947–2007 trajectory by this point. Productivity needed to grow more than twice as fast as it did.

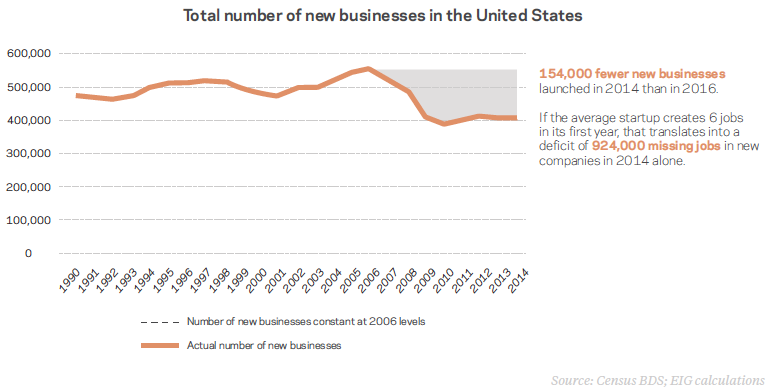

The economy has launched 25 percent fewer new companies each year since 2010 than it did prior to the recession. In 2014, the 154,000 new companies that went missing that year would have created nearly 1 million extra new jobs alone. The cumulative impact of the prolonged “startup-less” recovery on job markets — not to mention product, technology, and capital markets — is even greater.

2. Fewer new businesses means an economy with less margin for error.

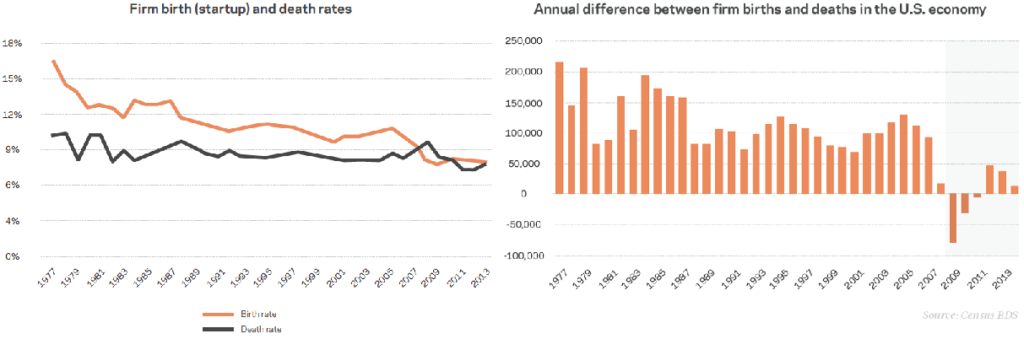

The Great Recession pushed the startup rate below the firm closure rate for the first time on record, and continues to hover near record lows. As a result, the U.S. economy is in the precarious position of barely producing enough new companies each year to replace those that close. Before the Great Recession, the number of firms in the United States rose by an average of 117,300 each year. In 2014, only 12,000 net new businesses were created. This is particularly troubling given that new businesses create nearly all of the net new jobs in our economy.

3. Diminished dynamism hits disadvantaged people and disadvantaged places the hardest.

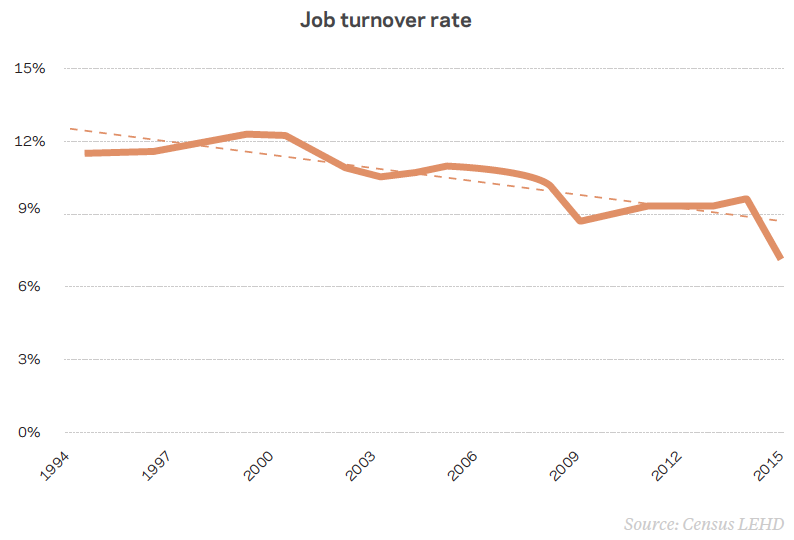

Previously, a highly fluid labor market used to facilitate upward economic mobility and enable people to climb the income ladder. Over the past two decades, though, the labor market has become much less flexible: the job turnover rate fell by more than 40 percent from 1999 to 2015. Now only one in every 14 positions in the economy turns over. Already-disadvantaged workers feel the impact of lower turnover rates most acutely. Fewer job openings mean fewer opportunities for individuals not currently gainfully employed — young people, under-skilled workers, or someone emerging from unemployment — to become so. Economists estimate that reduced churn exerts three times the negative impact on the employment prospects of young men with a high school degree than it does on those with a college degree.

The most disadvantaged places are on the losing end of diminished dynamism too. EIG’s Distressed Communities Index found that — far from lifting all communities — the recovery has served to pull distressed and prosperous places further apart. In the country’s most prosperous communities, the number of businesses increased by 8.8 percent and employment by 17.4 percent on average from 2010 to 2013. In the country’s most distressed communities, by contrast, the number of businesses fell by 8.3 percent and the number of jobs by 6.7 percent.

4. A less dynamic economy makes for a less mobile society with less access to opportunity.

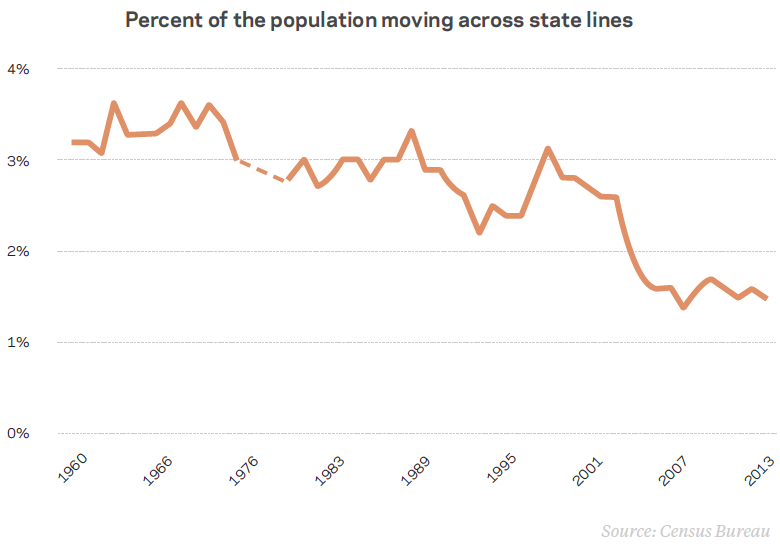

The fluidity with which Americans switch jobs and move across the country used to provide the United States with a key economic advantage — one closely linked with economic and social mobility. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, over 3 percent of the country’s population moved states each year. Over subsequent decades, though, the migration rate has more than halved. The trend holds for every cross-section of society. More and more Americans are stuck in place. With regional inequality rising and the link between economic opportunity and geography strengthening, geographic immobility threatens to cement economic inequality in place, too.

5. Big metro areas are driving an ever-larger share of new economic activity, leaving smaller cities and rural areas behind.

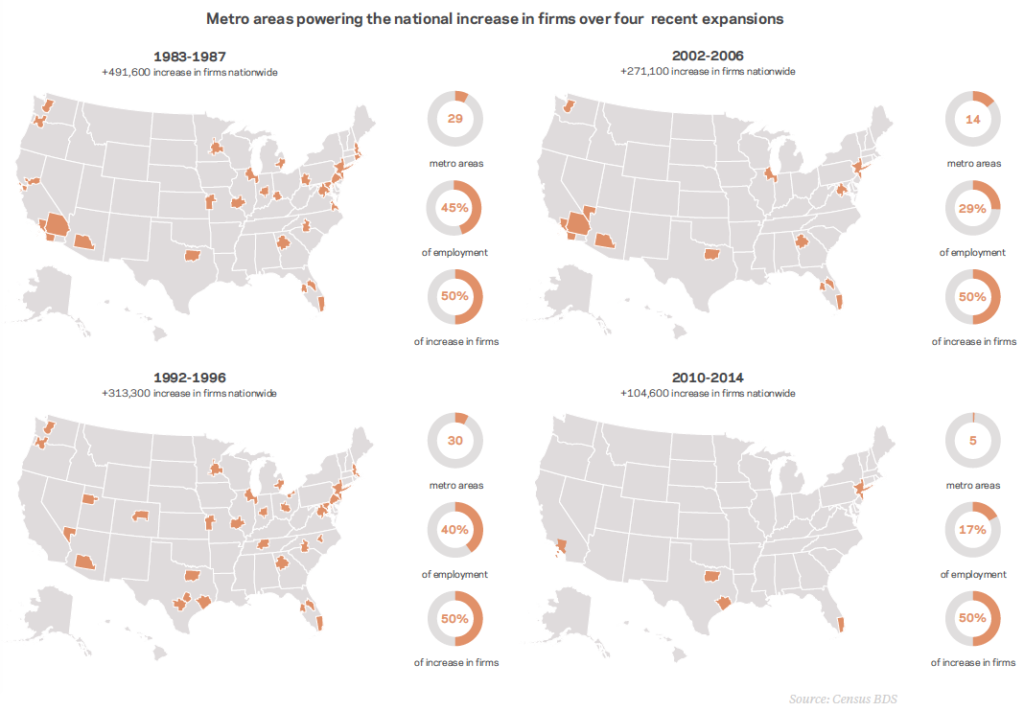

This recovery truly was different: The economy added only about one-fifth the number of firms from 2010 to 2014 that it did from 1983 to 1987, the first five years of the 1980s recovery. To boot, the largest metro areas garnered much larger slices of this smaller pie. Only five metro areas — New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Houston, and Dallas — containing just 17 percent of the employment base claimed half the net national increase in companies from 2010 to 2014. In the 1980s, fully 29 metro areas containing 45 percent of the country’s employment base accounted for the same amount of growth. To put the magnitude of the shift into perspective: in 2014, 61 percent of the country’s metro areas were still “underwater” with more firms closing than opening; in 1987, the figure was only 6 percent.

6. Growing economic power of big incumbents will make it difficult to restore dynamism.

Declining dynamism and rising incumbency have gone hand in hand. As incumbents loom ever-larger over industries and markets, it’ll only grow even harder for new companies to break in. In fact, the dominance of established companies may already be contributing to lower rates of survival among even the most promising young companies posted in recent years.

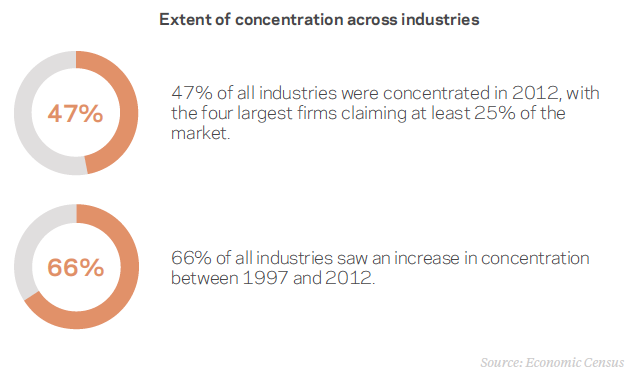

The facts: The share of the workforce employed in companies at least 16 years old has risen steadily each year to a high of 74 percent in 2014, just as the share employed by new companies has fallen to an all-time low. Established firms are grabbing ever larger market shares too. Between 1997 and 2012, two-thirds of the country’s industries saw an increase in market concentration. By 2012, the four largest firms captured at least 25 percent of revenues in nearly half of all U.S. industries. Meanwhile corporate profits have climbed to a record 9.4 percent of GDP as the lack of entrepreneurship weakens competitive pressures.

Closing Thoughts:

The Great Recession pushed all measures of dynamism so low, and the recovery from those low-points has been so meager, that the economy remains extremely vulnerable. We’re wholly unprepared for the next recession. How many firms will the economy lose when it inevitably hits? How much more of each industry will dominant incumbents seize? Will the last few resilient metropolitan hubs fall underwater too? Will the economy’s creative forces be rendered completely inert?

Policymaking in an era of retreating dynamism should focus on empowering individuals and firms to take the kinds of entrepreneurial risks that are crucial to a healthy and competitive economy. The United States faces a creation problem, not a destruction one. Only by restoring the economy’s creative forces can we restore the economy’s dynamism and promise.