by Connor O’Brien and Kenan Fikri

A House and Senate conference committee has begun negotiations to unify two sprawling packages of competitiveness legislation. The House’s COMPETES Act and the Senate’s United States Innovation and Competition Act (USICA) goals are to boost America’s science and technology ecosystems to out-compete China both militarily and economically. But reconciling different approaches in how to get there – how to address the challenge of speeding up technological and scientific progress in key strategic industries – and what else they try to accomplish along the way is the key challenge facing the Conferees.

The Bipartisan Innovation Act that will emerge from the conference reflects a growing, bipartisan consensus that the United States needs to better tailor its research and development policy towards creating and commercializing new technologies. The need is evident from the decades-long slowdown in productivity growth, the concerning sclerosis plaguing many areas of federally-funded research, and the growing geopolitical need to compete with major strategic adversaries such as China.

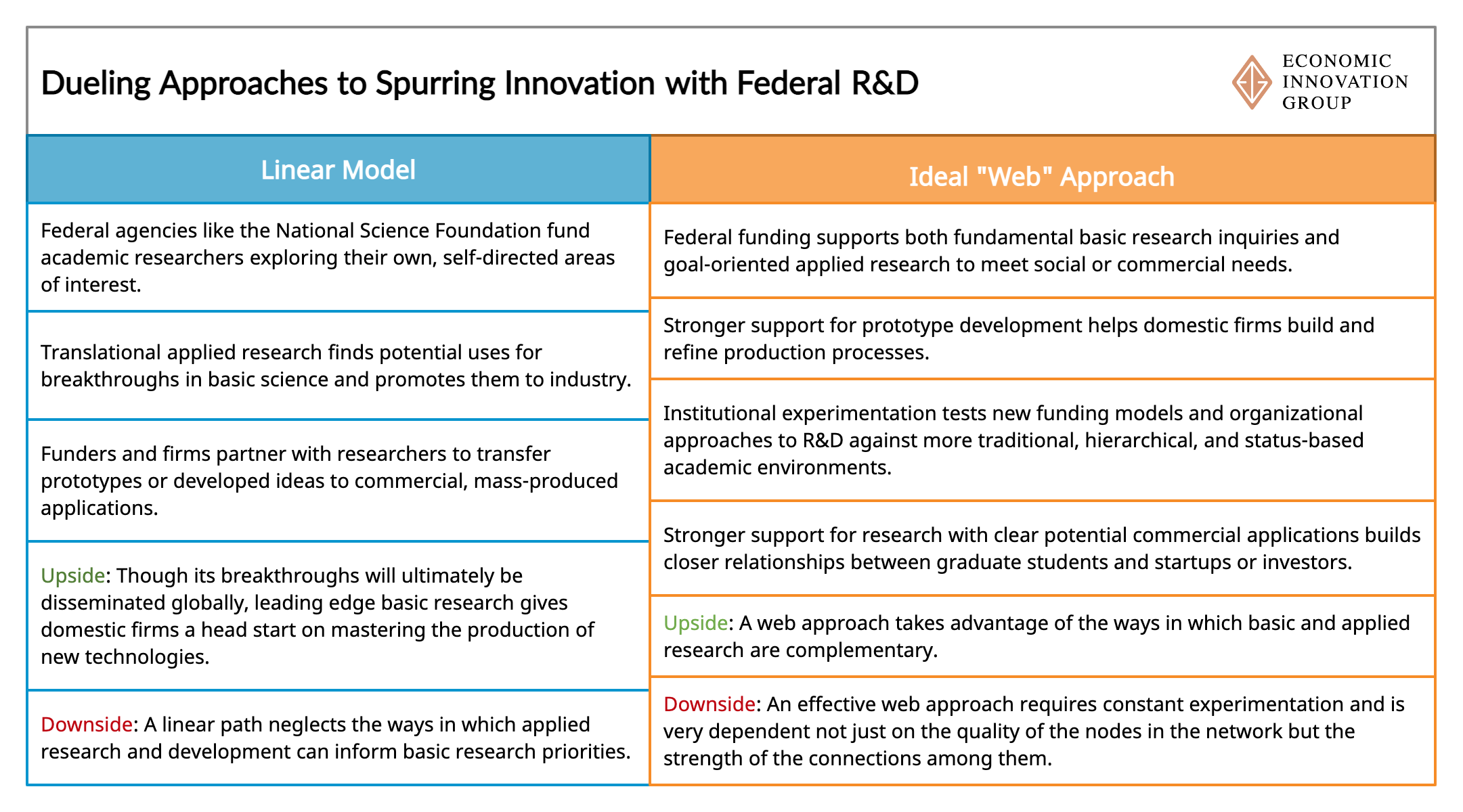

Yet competing theories about how innovation happens are evident in the two bills. On scientific research funding, the House approach ascribes to a more “linear” and traditional theory of innovation that seeds the earliest-stage basic research and assumes downstream innovations will make it to market from there. By contrast, the Senate version seems to regard innovation as a more iterative process and places more emphasis on later-stage applied research, closer to market applications. The House approach is best evidenced in its $50.3b investment into the Department of Energy and the business-as-usual approach it takes to the National Science Foundation (NSF), the nation’s two quintessential basic research agencies, while the Senate approach is best evidenced in its explicit emphasis on 10 key technology areas, stronger funding for the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, and the culture-shifts and mission-driven focus it tries to instill into the NSF.

On immigration, the House bill recognizes the critical role that talent plays in technological progress and the limits of funding alone. Given the large investments the ultimate Bipartisan Innovation Act will make in semiconductor manufacturing, for example, it’s critical that Congress gives firms building out production in the United States access to the talent they need.

Finally, the House and Senate bills are in agreement on the need to make sure these strategic investments in science and technology bring opportunity to every corner of the country. The regional technology hubs prescribed by both pieces of legislation could spur deep investment in some regions that badly need it.

Both bills take important steps to improve innovation policy, but their differing emphases lead to important distinctions in how they would reshape the role of the federal government in the nation’s innovation enterprise. Conferees should adopt the Senate’s laser-like focus on applied research, the House’s embrace of human capital as a crucial input in the innovation process, and the shared emphasis on regional industry hubs as where commercialization happens. Overall, the Senate bill is more scoped towards the needs of the moment, particularly the need to counter aggressive Chinese industrial policy in strategically important technologies. After consolidating the common ground, conferees should tack in that direction while lifting the best aspects of wider-ranging the House bill.

R&D: Double down on basic research or experiment and commercialize?

Traditionally, the United States’ federal R&D system has taken a linear approach to stoking innovation seen in the House version, wherein the government funds basic scientific research (often at universities or federal laboratories) that yields discoveries whose social and commercial applications are then picked up by the private sector–or not. In some cases this process works well, but technology often does not take a straightforward, linear path from fundamental discovery to applied research to commercialization and mass production. Indeed, much of this federally-funded research ends up being conducted for its own sake, with the goal of learning more about the universe, not necessarily introducing a new industrial process or bringing a product to market. This long-standing approach to science funding has underlined NSF decision-making for decades, but is overdue for modernization.

In practice, scaling up a production process itself often feeds useful lessons into a cycle of constant innovation and improvement. This is one reason that the nation’s technologists regret that the United States has offshored so much production know-how and with it, derivative innovations–because such feedback loops are at the very heart of modern innovation. Meanwhile, many of the federal government’s most resounding R&D successes have been goal-oriented applied research programs that set out to produce unique systems for government or commercial use and deliver revolutionary popular technologies in the process. The history of DARPA famously demonstrates the value of applied research at its best, seeding groundbreaking innovations like voice recognition, GPS, and the internet. The ideal discovery-to-innovation pipeline is not a pipeline at all, but a web of linkages between scientists, industry, government, and investors. The “web” approach, in contrast to the traditional linear model, takes full advantage of feedback loops among actors and processes.

Both bills nod to the web-based nature of modern innovation, but the Senate bill appears to be more tightly focused on not just mastering the technologies of the future, but ensuring they get applied in the economy and society. Choosing between basic and applied research is, of course, a false dichotomy. They are complementary, and each is its own building block of long-run economic and technological growth. However, as Nobel economist Paul Romer has argued, we need not choose between scientific and technological leadership, but we have neglected the latter, forgetting the enormous role that applied, use-focused research played in the country’s explosive early 20th century growth.

A consensus around the need for institutional innovation; differing perspectives around how

The two bills’ competing philosophies around scientific innovation are readily apparent in how they approach the institutional innovation at the heart of the debate.

At the center of both bills are proposals for a new technology directorate within the National Science Foundation that would become a focal point for setting national technology development priorities and support programs that shepherd early-stage research through to commercialization in those areas. In contrast to much of the federal government’s non-defense R&D programs, this directorate will explicitly direct research towards projects with clear commercial applications, particularly those in industries deemed key to national and economic security. As Romer writes, the lack of institutional diversity, and the tight control the academic community has over grant-making and prioritization, are holding back American technology. Proponents of a new technology directorate from both sides of the aisle argue that we need to experiment with new institutional cultures more directly focused on developing useful commercialized technologies. It is apparent from the bills’ details that the Senate version is better positioned to actually trigger this all-important culture shift.

The House’s COMPETES Act directorate has less than half of the funding level ($13 billion through 2026) in USICA and a mandate that pulls it in many different directions, risking a lack of focus. Its directorate’s mission includes climate change issues, economic and social equity, and workforce development. Further, the House’s directorate is more closely tied to its parent agency than the Senate’s in that it allows the NSF to potentially claw back some of its funding in the future. The Senate bill only allows a one-way transfer of funding from the NSF to the new directorate.

The Senate’s USICA funds its new Directorate for Technology and Innovation at $29 billion over the next five years, $4 billion of which will go directly to R&D. The technology directorate’s mission is focused on spurring development in 10 key technology areas, including robotics, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, batteries, and quantum computing. The new directorate will also get funding for technology transfers, scholarships, demonstration facilities, and innovation centers at universities throughout the country. With a narrowly-scoped, focused mission, USICA’s directorate could serve as a future model for nimbler, more flexible federal research institutions.

In short, USICA’s directorate will be better equipped to address the so-called “valley of death,” the set of steps between fundamental scientific discovery and scaled-up commercial production, that has plagued key advanced technology sectors in the United States relative to China and other competitors more ruthlessly focused on commercial applications. The United States has a productive non-defense basic research system based on the idea that academic scientists and researchers left to pursue their own curiosities without too much priority-setting from outside bureaucracies will produce breakthrough discoveries that may ultimately prove useful to society or firms. This research pipeline has, in fact, become the envy of the world in some respects as an engine for fundamental discoveries, but often struggles to translate early pioneering research into technological and economic leadership. USICA’s technology directorate is better designed to solve this challenge.

Reforming federal R&D funding should not be taken lightly. Even imperfectly structured basic research is a fundamental building block of long-run growth that botched reform could undermine. But just as firms in a dynamic economy constantly come and go, or expand and experiment, in response to economic change, so too should our research agencies. We are long overdue for some institutional experimentation, and a relatively autonomous, commercialization-focused directorate within the NSF as outlined in USICA is surely an experiment worth undertaking.

Immigration: Recognizing that talent matters for economic dynamism

Immigration is perhaps the area where USICA and the COMPETES Act differ the most–and represents one realm in which the more expansive nature of the House bill gets things right. The Senate’s bill doesn’t touch immigration policy and therefore misses an opportunity to up our game in the intensifying global race for technical talent.

The House bill contains two bold new visa programs to attract foreign entrepreneurs and graduates of STEM PhD and master’s programs. On this front, the House bill’s changes would substantially boost the competitiveness of American firms on the technological frontier in key industries and is an important step towards reversing the country’s long-term decline in economic dynamism. Unfortunately, there is reason to doubt the fate of these immigration provisions in conference committee negotiations because of the typical partisan sticking points around immigration. Congress’ inability to do everything on immigration has rendered it incapable of doing anything on immigration. This undermines the goal of restoring American technological dominance by starving the country of indispensable talent, and the Congress should not miss the opportunity to advance our national interests around skilled immigration in its competitiveness bill. Despite their slim prospects of passage, it is worth examining the immigration components in detail.

First, the bill codifies a new set of “W” start up visas, essentially making permanent the International Entrepreneur Rule (IER) run out of the Department of Homeland Security that temporarily admits entrepreneurs building high-growth potential firms in the United States for stays of up to five years. Devised late in the Obama Administration, implementation of the IER languished under President Trump before being reactivated by the Biden Administration.

The new W-1 visa program envisioned in the House bill would grant three-year stays to entrepreneurs with an ownership interest in an American startup. An entrepreneur can extend his or her visa by an additional five years if the startup has received at least $500,000 in qualifying investments, created at least five jobs, or generated $500,000 in annual revenue and averaged 20 percent annual revenue growth. Under the House bill, a similar W-2 visa will be available to key employees working in executive or managerial roles at American startups, with two visas made available to small firms with 10 or fewer employees, or up to five for firms with more than 70 employees. These visas can be extended an additional three years. Finally, a third category of W-3 visas would be available to spouses and children of W-1 and W-2 visa holders who would also be eligible to work in the United States. More than a dozen other countries have successful startup visa programs, including Australia, Canada, Chile, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

COMPETES’ boldest and most creative immigration provision is its exemption of foreign STEM PhD graduates (and master’s degree holders working in key defense industries) and their family members from numerical visa caps to work at American firms in science and technology-related fields. This would dramatically improve the availability of top global talent in science and technology fields for American firms–relieving a binding constraint on innovation in the United States.

The House’s approach is superior because it recognizes the human capital constraint on the growth of high technology firms across the country. Each bill puts billions behind reshoring key advanced manufacturing firms and supply chains, especially semiconductor fabrication and research, to the United States. Subsidies alone, however, are unlikely to produce or sustain firms at the absolute technological frontier. Advanced industries subsist on workers with the experience, know-how, and hard-to-replicate tacit knowledge that comes with incredibly complex, iterative manufacturing processes. As immigration expert Jeremy Neufeld lays out in a recent piece, the defense-industrial base relies heavily on foreign-born, STEM-trained workers, and major semiconductor firms have cited insufficient domestic talent as a major deterrent to investing in scaling up production in the United States. The purpose of this new competitiveness legislative effort is to seize global technological leadership in areas like robotics, biotechnology, medical technology, cybersecurity, batteries, and materials sciences, and this cannot be accomplished without an adequate supply of the right human capital.

Second, the COMPETES Act’s immigration provisions are by no means a substitute for upskilling domestic workers in STEM fields. In fact, the bill is designed to complement this goal. Petitions for W visas and for status as a cap-exempt STEM degree holder come with $1,000 fees whose revenue will be recycled to fund scholarships for low-income American students pursuing STEM degrees. There is already substantial empirical evidence that the presence of high-skilled foreign workers makes domestic workers (and domestic firms) more productive. Under this COMPETES provision, the inflow of top foreign talent will also help nurture some of the next generation of domestic STEM graduates.

Third, the House bill levels the talent attraction playing field between large incumbent technology companies and their smaller, upstart competitors. The H-1B visa program, the largest source of foreign talent for science and technology firms in the United States, is cumbersome and expensive for small firms. H-1B applications, far from guaranteed to yield an actual visa, cost firms thousands of dollars each. A straightforward cap exemption for foreign STEM graduates would lower costs for startups and open larger pools of talent to young, cash-strapped startups.

Any legislation serious about rebuilding and strengthening American technological dominance in some of the 21st century’s most important industries–and building a more dynamic, innovative economy along the way–would include the immigration provisions in COMPETES. Instead of allowing these provisions to get bogged down in the traditional immigration debate, the conference committee should recognize that these two new sets of visa pathways are at their core about competing with China and ensuring that the billions allocated to semiconductor manufacturing and reshoring of key strategic industries actually translate to technological dominance, not about circumventing long-standing divides on immigration policy.

Regional Technology Hubs an important point of agreement

One area in which the COMPETES Act and USICA are in close alignment is their creation of Regional Technology Hubs through the U.S. Department of Commerce. This represents a shared bipartisan, bicameral recognition of the importance of geographic industry clusters in fostering innovation. COMPETES, with funding of $7 billion over the next five years, calls for at least 10 hubs, while USICA (with $10 billion in funding) calls for the creation of at least 20, each relating to one or more of the bill’s 10 priority technology areas. USICA would spread funding more thinly, in other words–the contrast reflecting a policy trade-off between investing deeply in a few potential ecosystems versus trying to seed multiple in a wider portfolio of federal bets.

Technology hubs are envisioned to be consortiums of local governments, economic development groups, private enterprises, labor unions, non-profits, and universities working to promote emerging technologies, conduct research, coordinate economic development, connect university researchers with entrepreneurs, and disseminate best practices throughout the region. Consortiums will apply for both strategy and implementation grants. While COMPETES houses the program directly within the Department of Commerce, USICA tasks the Economic Development Administration with administration in coordination with the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

The concept of technology hubs, “growth centers,” or industrial clusters has been promoted by economists and policy analysts across the political spectrum as a way of both incubating growth (they often represent the physical manifestation of the decentralized, iterative innovation ecosystems that power modern knowledge creation) and spreading economic growth more broadly. Regional development consortiums covering sufficiently broad areas with involvement of an area’s largest public, private, and non-profit enterprises can close information gaps, build relationships between firms, researchers, and potential suppliers. Under both bills, the Commerce Department would require consortiums to work in cooperation with Manufacturing USA institutes and Manufacturing Extension Partnership centers to coordinate regional growth strategies.

Each bill seeks to spread out new regional technology hubs and place them away from existing high-performing technology clusters as a means to incubate more advanced technology growth poles in the country. The Senate’s bill requires at least three hubs in each of the six EDA regions. The Senate bill directs the EDA to focus its efforts on small and rural communities. The House bill does the same, but with an additional focus on underserved minority communities.

Regional development hubs, when designed to build on existing local assets, focus on long-run growth, and facilitate the commercialization of local university-based research, can deliver real results for targeted communities and the country as a whole (indeed, the cluster concept was originally introduced into federal policy discussion under the header “The Regional Foundations of U.S. Competitiveness”). However, regional technology hubs that attempt to build industry clusters from scratch–or from much less than a critical mass of inputs, assets, and actors–are much less likely to be successful. USICA’s requirement that regional hubs fit at least one of the bill’s 10 key technology areas is laudable, but it may also steer applicants away from their true competitive advantages in the hopes of landing one anyway. And in some cases, the drive to decentralize innovation activity geographically may be at odds with the logic of agglomeration, which ensures that critical masses of the essential ingredients for innovation are present. Hubs sited in places with little relevant expertise or assets risk becoming very expensive white elephants–squandering not just run-of-the-mill federal spending but precious dollars intended to secure the country’s technological preeminence. Political pressure may pull hubs away from where they may be most immediately productive. In some cases, this will be in the country’s long-term interest anyway: a more balanced economic geography is essential to renew the cohesiveness of our national polity and diversifying the “what” and “where” of American innovation. But a delicate balancing act of competing interests and goals is guaranteed.

These two concerns should be top-of-mind as Commerce lays out criteria for potential technology hubs. Both the COMPETES Act and USICA give administrators wide leeway in evaluating hubs’ strategic plans and selecting awardees. Whether regional development hubs that emerge from this effort are successful will ultimately depend on Commerce learning from past clustering and growth pole programs and carefully identifying places where a federal infusion of money will truly set mid-tier regions on a different trajectory–while advancing national development at the same time. The final framework should allow regions to play to their strengths, and if Congress’ primary goal is to invest in the capacity of a new crop of innovation hubs, then it should not be overly prescriptive in how exactly those hubs should specialize. Advanced industry clusters emerge; they are not ordained. Here the compromise position may be to allow for the flexibility in the House version while offering guidance or priority points to applicants focused on the Senate’s key technology areas.

Conclusion

There is much to like in both chambers’ innovation bills, and it is refreshing to see policymakers think seriously about economic competitiveness, resiliency, and the barriers to producing and scaling up revolutionary technologies in the United States. The best amalgamation of these two bills will be based on the recognition that innovation and technological progress require federal support for critical inputs–dollars and talent–as well as how those inputs come together via institutions and ecosystems. That makes provisions around directorates and regional hubs equally as important as those pertaining to agency budgets and immigration.

It is worth emphasizing that last point, given the poisoned politics around immigration and the temptation policymakers will face to remove it from the final bill. New technologies and the industries they spawn will not take root in the United States if the supply of available talent is limited–just as a $52 billion nominal investment in semiconductors will yield little for the country if experienced workers are not available to match. From rocketry to computer chips, immigrants powered the modern era of American technological preeminence. High-skilled immigration is truly inseparable from any federal effort to secure that preeminence for the next one.

In the end, world-class basic research in American universities and laboratories will not lead to global leadership at the technological frontier unless paired with a system that efficiently shepherds scientific advancements through to commercial application. As the conference committee narrows down the final provisions of the bill, it should stay focused on this goal and on comprehensively dismantling the barriers standing in the way of American technological competitiveness in key global markets.