By Kennedy O’Dell

The U.S. Census Bureau’s new and experimental Small Business Pulse Survey provides weekly insight into the condition of the country’s small business sector as this unprecedented economic crisis unfolds. This analysis covers data from the week of September 13th to September 19th.

Here are five things we learned about the small business economy last week:

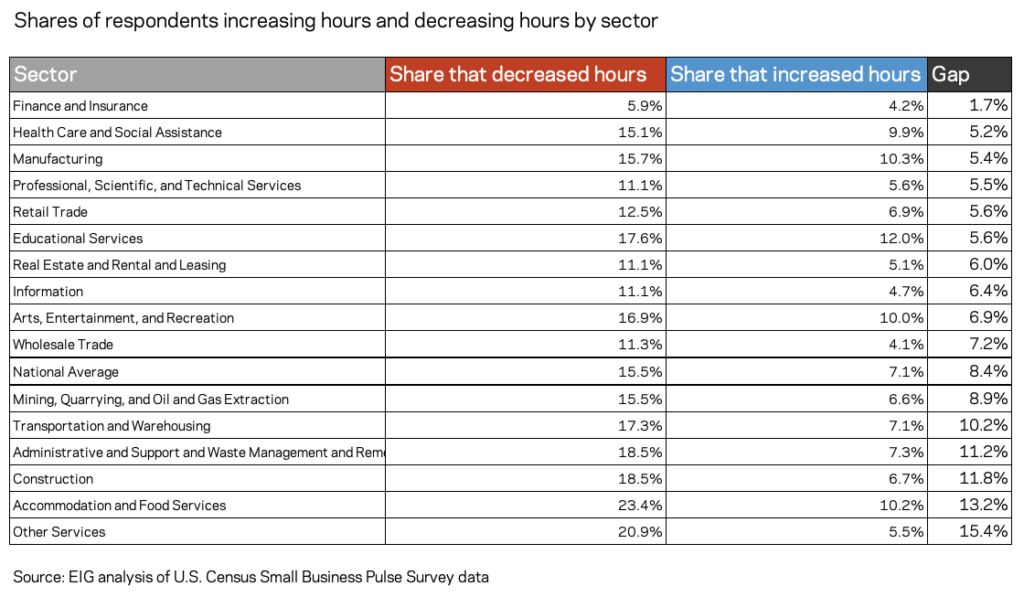

- While the pandemic has hit certain sectors harder than others, trends in employee hours imply that no industry is immune. More firms are cutting employee hours than are adding them across every sector of the economy. Nationally, 7 percent of firms increased employee hours while 16 percent decreased them.

- The finance and insurance sector looks closest to turning the corner. The gap between the share of small businesses increasing employee hours versus decreasing them has narrowed significantly in the finance and insurance sector, signaling that small finance and insurance businesses may be closest to widespread stabilization and recovery. The share of small businesses decreasing hours hovers about 5 percentage points higher than the share adding hours across a large cadre of sectors that includes manufacturing, health care, and education. At 23 percent, the accommodation and food services sector has the highest share of firms decreasing hours while the educational services sector leads on gross percentage of firms increasing employee hours, which might be expected at the start of the school year.

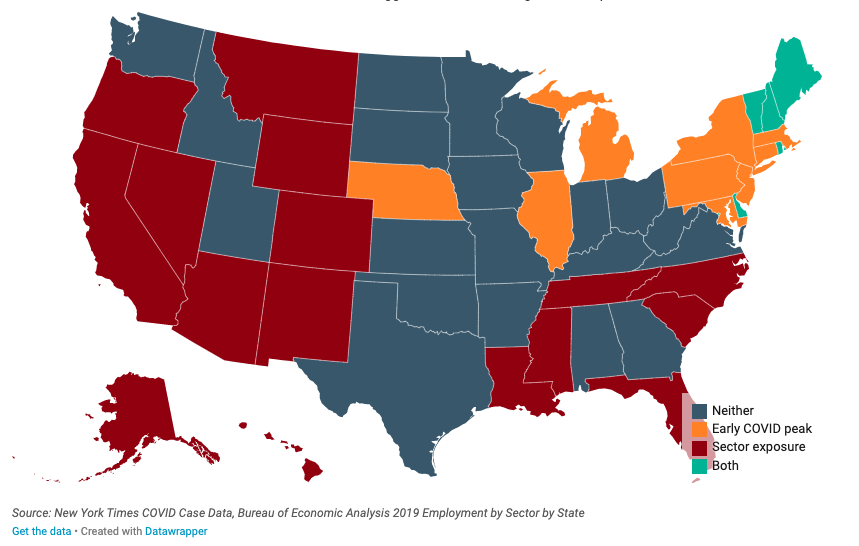

- An initially weak relationship between new cases of COVID-19 and declining small business revenues seems to be weakening further. New COVID cases and declining revenue for businesses in a state are not as closely linked in the short term as one might expect. There is no significant statistical relationship between new COVID cases per 100,000 people and the share of small businesses reporting weekly declines in revenue or the share of small businesses cutting employee hours at the state level. Instead, it looks like a combination of the orientation of a state’s economy, whether it was a first or second wave state, initial lockdowns, and other factors related more to the macroeconomic environment rather than local health conditions, are behind the continually decreasing revenues.

- Which begs the question, which states are struggling more — the places with the highest COVID case counts, or the places with the highest percentage of state employment in hard-hit sectors? The pandemic has hit certain places and sectors particularly hard. Some states are struggling because their economic orientation left them particularly vulnerable to shut downs and demand lapses caused by fear of in-person interaction—think of Hawaii or Nevada. Businesses in early virus hotspots also appear to be struggling more than businesses in regions where the virus peaked later. Such early-impacted states make up a significant portion of those with an above average share of businesses reporting a large negative effect of the pandemic, even in September. Lessons and adaptations that disseminated faster than the virus did itself across the country may have helped small businesses in other regions avoid even worse economic effects. Small businesses in second-wave states also surely benefitted from having a more complete small business support and survival policy infrastructure in place before the virus hit them the hardest.

- Cash on hand has not improved significantly since June. From the last week of April 26th to the week of June 21st to 27th, the share of businesses reporting enough cash on hand to cover at least three months of operations rose from 17 to 27 percent but has hardly moved since then.

- 27 percent of businesses are functioning as they were pre-pandemic, meaning 73 percent are not. Ten percent of small businesses report having returned to normal operations and 16 percent report little to no effect of the pandemic, meaning a cumulative total of 27 percent of businesses are now operating at pre-pandemic levels. By contrast, a clear plurality of small businesses think their crisis is far from over. Nearly half of all respondents (46 percent) expect to be stuck in limbo for the foreseeable future and do not anticipate a return to pre-pandemic levels of operations for at least six months.